Pediatric Transgender Care and the Contentious Rise of SEGM

William Malone recalls sitting in a packed conference room at the Endocrine Society’s 2018 meeting when a prominent physician presented updated guidelines for treating people who identify as transgender, including youth. The guidelines, which remain in place today, say adolescents should have access to a range of medical interventions, including drugs that pause puberty, cross-sex hormones, and in some cases, mastectomies.

Malone was unsettled. He had spent about a decade as an endocrinologist, treating patients in New York and Idaho, and he knew that these interventions can have significant lifelong effects on children’s bodies. The evidence underpinning the Endocrine Society’s recommendations seemed remarkably weak to him. The guidelines, he said, were “just terribly done.”

The Endocrine Society told Undark that its 18,000 members were given the opportunity to comment on its guidelines and that the process leading up to their publication was no different than usual. Nevertheless, in the past few years, a gulf has opened up among physicians over fundamental questions about how best to respond to young people who seek medical treatment related to their gender identity.

In much of the United States and Canada, the standard practice is to offer puberty blockers and hormone therapy. These interventions, along with mental health and social support, are at the core of what is often referred to as gender-affirming care. Many people say the care is helpful for them, and this approach is supported by major U.S. medical societies, including the American Academy of Pediatrics. The AAP notes that young people who identify as transgender have high rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders. Gender-affirming care can help alleviate this distress, according to the organization’s policy statement, which says the approach is supported by “a limited but growing body of evidence.”

Following the U.S. approach, puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones were widely available in much of Europe until just recently. Since 2019, scientific reviews have been conducted in Finland, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Norway, and the U.K. to evaluate the benefits and risks for children. All have concluded that the evidence thus far is of low-quality. “This is an area of remarkably weak evidence,” states a major U.K. report on youth gender medicine published in April.

While psychological and social support for children experiencing gender distress will still be offered, several European countries have now restricted, or are moving to restrict, young people’s access to the medications over concerns that they may be harmful to some patients, and because the long-term outcomes are not well understood. A recent systematic review, conducted as part of the U.K. report, found that some of the medications impair bone density, and it underlined their unknown impact on young people’s brain development and fertility. In the U.K., new prescriptions for puberty blockers are no longer available for the treatment of gender dysphoria through the publicly funded National Health Service for people under 18. Cross-sex hormones may be prescribed starting at around age 16, but only to young people who meet strict criteria. Instead of these medications, the U.K. report recommends psychological interventions as the main approach to treatment.

In the past few years, a gulf has opened up among physicians over fundamental questions about how best to respond to young people who seek medical treatment related to their gender identity.

Against the backdrop of these rapidly diverging continental perspectives, Malone began looking for professionals who shared his belief that better research is necessary before youth are given access to puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, or surgeries. In 2019, he co-founded the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine, or SEGM (pronounced SEG-um). The group serves as a hub through which clinicians and researchers collaborate, and it has become an influential voice in the polarized global debate over pediatric gender care.

SEGM funds literature reviews and hosts events, including an academic conference last October, which drew speakers from around the world. Zhenya Abbruzzese, a health care researcher with a background in health economics and a SEGM co-founder, said that to date, the group’s biggest achievements have been to facilitate international collaboration and allow clinicians to share their views when they might otherwise be afraid to speak out.

These efforts have drawn sharp criticism from some supporters of gender-affirming care. In a 2022 report, researchers at Yale University and the University of Texas Southwestern characterized SEGM as “nothing more than a website.” The report also suggested that the group distorts data in a way that provides fodder for Republican-led states seeking to ban access to pediatric gender medicine. SEGM’s advisers, the researchers wrote, have not “published original empirical research on the medical treatment of transgender people in a peer-reviewed publication,” nor do they hold academic appointments in pediatric medicine or child psychology. (Abbruzzese insisted that SEGM collaborates with a wide range of clinicians and researchers beyond their named advisers — some of whom have published, she said, “empirical research on medical treatment of transgender people.”)

Other critics of the group point out there isn’t much evidence to back up psychotherapy. SEGM, citing guidelines in Finland and elsewhere in Europe, has described this as the preferred treatment for younger people. “As a researcher invested in evidence-based mental health practices, I’m concerned that SEGM has promoted untested alternatives to gender-affirming care,” Briana Last, a faculty member in the psychology department at Stony Brook University, wrote in an email to Undark. Others have accused people affiliated with SEGM of using inflammatory language. “It’s just pure bigotry, and really gives the game away of what they’re aiming to do,” said Alejandra Caraballo, a clinical instructor at Harvard University’s Cyberlaw Clinic who has written about the role of medical experts in court cases.

Even as some scholars and activists seek to label SEGM a pseudoscientific hate group, it has inarguably brought together clinicians and researchers who believe that the United States is becoming an outlier in its approach to pediatric gender medicine. SEGM insists that the evidence — or, more precisely, the absence of it — is currently on the group’s side. Among other things, they point to the U.K. report, which was commissioned by England’s National Health Service. Dubbed the Cass Review after the pediatrician who led the effort, Hilary Cass, the report concluded that more robust evidence is needed on every aspect of pediatric gender care, from puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones to psychotherapy and other forms of treatment.

For Malone, that finding echoed his longstanding concerns about the Endocrine Society’s guidelines: “When we’re intervening in a substantial way, putting the patients down a lifelong medicalized path, boy, there had better be quite substantial evidence that these interventions are beneficial.”

In 2018, when Malone returned from the Endocrine Society conference, he started checking in with colleagues to see if they shared his reservations about the guidelines. Some of them did, he said, but few would say so openly out of fear that it would damage their careers. Mainstream publications were wary of his ideas, he said, and in interviews with Undark, he stressed that his views are his own, not those of his employer. He was, though, able to co-author a letter to the editor in a medical journal run by the Endocrine Society.

Then he went to less scholarly venues.

In July 2019, he appeared in an interview with Benjamin A. Boyce, a free-wheeling provocateur with a following on YouTube. When Boyce mused that puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones could potentially “neuter a generation,” Malone said people harmed by the care would start to come forward. “When you apply unscientific principles to the real world, bad things happen,” he said. “And then eventually, those people who have had bad things happen to them start to stand up and say, ‘Look, something bad happened to me. Look at the consequences of applying this unscientific treatment protocol to real life. And eventually, the weight of the number of people hurt by this will, I believe, force some global awareness and change and reckoning.”

“When we’re intervening in a substantial way, putting the patients down a lifelong medicalized path, boy, there had better be quite substantial evidence that these interventions are beneficial.”

Later that year, Malone wrote a blog post for 4thWaveNow, a self-described “community of people who question the medicalization of gender-atypical youth.” Malone’s online opinions caught the eye of Abbruzzese, who was looking to create a group for professionals with concerns about gender-affirming care. Abbruzzese also reached out to Julia Mason, a pediatrician in Portland, Oregon, who had publicly expressed her own misgivings.

In a recent interview with Undark, Mason recalled referring children to a local gender clinic, and finding that in some cases, the treatments did not seem to help. One young person, prescribed testosterone, experienced incontinence and other side effects, Mason said, and as more children arrived seeking similar care, she became increasingly uneasy with what she considered a hasty and maximalist approach on the part of some gender medicine physicians.

She and Abbruzzese met face-to-face at a café in Portland to discuss their nascent group, which came to be named the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine. “The intention has always been to follow the evidence,” Abbruzzese said. Malone, Mason, and three other clinicians formed the board, and soon the group was up and running.

On key issues, the organization’s views were increasingly aligned with those of several major European medical institutions, which were beginning to restrict access to puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones. But the group soon ran into headwinds in the United States, and when they tried to engage with the AAP, they say they hit a wall.

SEGM said the group registered and paid for a virtual booth at the AAP’s 2021 conference, which was held online because of the pandemic. But their application was rejected before the start of the conference without explanation, Mason wrote in an open letter to the AAP. (The incident was reported in Medscape as well as in an opinion article in The Wall Street Journal.)

On its website, SEGM accused the AAP of silencing debate: “This rejection sends a strong signal that the AAP does not want to see any debate on what constitutes evidence-based care for gender-diverse youth.” (The AAP did not respond to specific requests for comment on SEGM and the conference booth.)

Mason also attempted to directly petition the AAP to review its guidelines on gender transition. She submitted two resolutions for 2020, but they stalled because they did not have a sponsor — essentially, someone in AAP leadership who supports the idea and will pass it along to the national level. In 2021, Mason said, an Indiana-based pediatrician submitted a similar resolution, which was seconded by the then-president of the AAP Nevada chapter, but the AAP leadership voted it down.

The following year, Mason and four colleagues banded together to craft another resolution, but again faced roadblocks with sponsorship. In comments appended to the AAP’s agenda document for the 2022 AAP leadership meeting, which was leaked to the Daily Mail and subsequently verified by Undark, some members registered concerns that that resolution was blocked. “I can no longer trust the AAP to provide medical evidence based education with regard to care for TGD individuals,” wrote one Tennessee pediatrician. “This past year at the AAP national conference, ongoing debate on the matter was silenced egregiously.”

While SEGM was seeking a place at medical conferences, Republican lawmakers were turning their attention to pediatric gender medicine, and sometimes citing SEGM to bolster their positions.

In recent years, almost half of U.S. states have moved to limit or ban access to such care, with an impact that Harvard’s Caraballo, who is transgender herself, described as “mentally taxing and emotionally burdening.” Two Republican-led states, Florida and Texas, have referred to data and research summaries on SEGM’s website in commissioned reports and legal guidance. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton cited SEGM twice in a 13-page opinion arguing that providing minors with puberty blockers, hormones, or gender-transition surgeries could constitute child abuse.

Malone said SEGM isn’t responsible for how others use its materials, but some scholars have argued that the group disseminates biased information that has helped to drive this trend. In 2022, the Yale-led team published its report examining the way politicians in Texas and Alabama deployed science to justify restrictions on gender medicine. The paper accused SEGM of, among other things, distorting data about the number of youth seeking treatment.

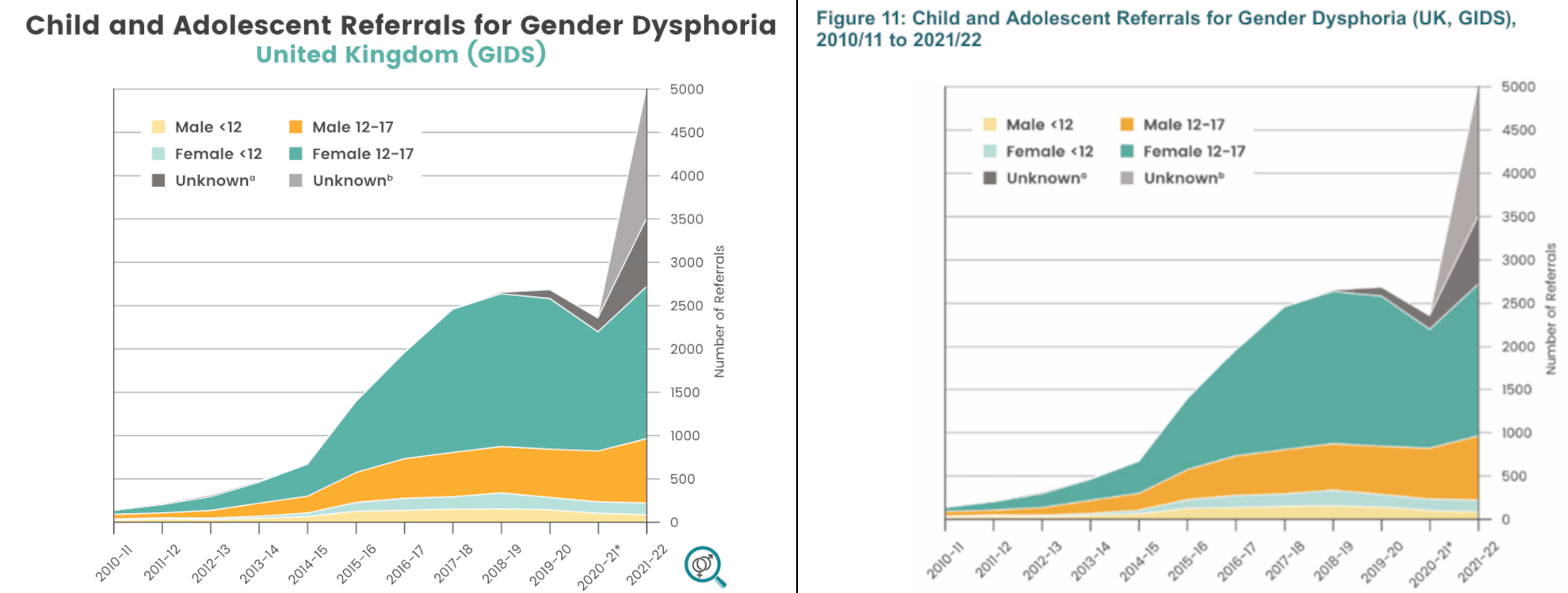

A graph on SEGM’s homepage, cited in the Texas Attorney General’s opinion, shows a sharp increase in referrals to the London-based Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service, or GIDS, which was the world’s largest youth gender clinic until its recent closure. The chart shows that from 2010 to 2022, referrals rose by more than 5,000 percent. “The graph is calibrated to look as if the increase is very large,” the Yale report authors wrote, “but in fact, the absolute numbers are small.”

In an email to Undark, Meredithe McNamara, an adolescent medicine physician and one of the paper’s authors, elaborated: Just a tiny proportion of British children and teens — less than 0.04 percent, or 4 in 10,000 — sought care during this time period, she wrote. And this increase, she said, should be viewed as a positive development, as it builds on more accurate diagnostic criteria, and suggests that stigma decreased and allowed more young people to come forward.

The Yale report authors also wrote that SEGM’s advisers do not have the relevant experience or expertise to comment on gender medicine. They described the group as “an ideological organization without apparent ties to mainstream scientific or professional organizations.”

The lack of expertise is important, wrote McNamara in her email. “When we thoroughly vetted the original members’ credentials in early 2022, we noted with interest that none cared for transgender patients and thus had no clinical experience with the matters at hand,” she said. “The subsequent addition of a handful of individuals with medical training does not confer upon SEGM any standing as a legitimate medical association, particularly given that its views are roundly repudiated by every major U.S. medical association and the World Health Organization.” (The WHO does not currently have guidelines on gender care for children, though it recently extended a deadline for feedback on guidelines relating to gender care in adults.)

Malone characterized the Yale report as “a hit piece” focused primarily on personal critiques. Most SEGM collaborators are active clinicians and researchers, he told Undark. These include family doctors, pediatricians, endocrinologists, psychiatrists, gynecologists, and plastic surgeons, among others, Malone said. Some have worked with young people who changed direction after thinking they might be trans, he added. Others worked in gender medicine before developing concerns about the field’s direction.

Richard Byng, one of SEGM’s advisers and a professor of primary care research at the University of Plymouth in the U.K., said that the Yale-led team’s critique of the graph illustrates a substantive point of disagreement: “What they are saying is that it’s a small proportion of the population. You can’t conclude from that that you shouldn’t be concerned about it,” he told Undark.

McNamara said that SEGM is committing “grave scientific misconduct” by posting a “distorted data schematic that is then used by a government to justify a cruel and unscientific policy that harms youth and families.”

Across the Atlantic, SEGM’s graph seems to have been well received. The same chart appears on page 85 of the Cass Review. Neither Hilary Cass nor NHS England responded to questions about the origin of the graph, but in an email, Abbruzzese wrote, “We also noticed our chart in the Cass Review and were both surprised and pleased (although we saw no attribution to SEGM).”

In an email to Undark, Erica Anderson, a psychologist who is transgender and who has helped young people to transition, described SEGM as the most important group of clinicians and scientists working in youth gender medicine. “The group does not exist so much to oppose gender-affirming care as to determine the best approach to gender-questioning youth,” she said.

SEGM believes psychological support should be offered as an alternative treatment. This would include modalities like exploratory therapy, which aims to allow for a critical exploration of gender stereotypes as a way of addressing distress. This emphasis on psychological support aligns with current health policy in several other countries, including Sweden, Finland, and the U.K.

Roberto D’Angelo, an Australia-based psychotherapist and psychiatrist and SEGM’s current president, acknowledged the need to study psychological interventions in youth who would otherwise receive gender-affirming care. But psychotherapy, he noted, has proven effective in resolving many kinds of psychological distress. “Yes, the evidence for psychotherapy for gender dysphoria is extremely limited,” he told Undark. But, “we have robust evidence to show that psychotherapy is helpful in a range of conditions that involve emotional distress, including problems about body self-image, identity problems, and so on.”

(In previous years, SEGM argued that psychotherapy was the preferred treatment for patients 25 and under, though it no longer specifies any age at which medical interventions would be appropriate, citing ongoing research into various age groups.)

One reason to be cautious about medicalization, said Mason, is that not all kids will continue to identify as transgender in adulthood. “I’ve met too many detransitioners to believe that gender identity is internal, eternal and immutable,” she wrote to Undark in an email. Mason and others affiliated with SEGM worry about detransitioners — a group that includes people who decide to stop taking hormones in order to return to their natal, or assigned, sex. Young people who detransition have reported that when they stop taking hormones, some of the medication’s effects linger, possibly causing permanent changes in voice, vaginal dryness, and increased body hair.

The exact number of detransitioners is unknown, and some have suggested that they represent just a small minority of patients, and exercise an outsized influence on conversations about gender medicine. The Cass Review outlines a number of factors that make it difficult to count detransitioners. Among them, patients don’t always return to their gender clinic when they decide to detransition, and some adult clinicians report that detransition often occurs five to 10 years after the start of treatment — too far off to be captured in short-term studies.

“The group does not exist so much to oppose gender-affirming care as to determine the best approach to gender-questioning youth.”

One detransitioner, Isabelle Ayala, is now suing the AAP and the lead author of the organization’s 2018 guidelines, Jason Rafferty, who allegedly prescribed her testosterone after a single meeting lasting less than an hour. The suit accuses the AAP, Rafferty, and other clinicians of fraud, medical malpractice, and a “collective failure to treat her properly.” (Rafferty did not reply to several requests for comment.)

On several occasions, SEGM and SEGM advisers have communicated their views to decision makers. For example, in 2021, the group submitted an amicus brief in a case in which two teenagers unsuccessfully petitioned Arizona’s Medicaid program to pay for chest surgeries. SEGM has presented its perspective to the Department of Health and Human Services, and Malone has petitioned the FDA to investigate the off-label prescription of puberty blockers, requesting that studies be conducted. In 2022, when politicians in Idaho debated a bill that would criminalize prescribing puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones to gender dysphoric kids, Malone testified as a neutral party, stating there was a lack of evidence about the treatment’s effectiveness. The following year, he again testified for a similar bill. (In both cases, he spoke in an individual capacity and not in relation to SEGM.)

These activities have drawn pushback from people who have a very different understanding of the science — and of the role of physicians in medical decision-making. Many trans rights advocates, including Caraballo, say that physicians should not serve as gatekeepers, restricting access to medical care. Practitioners often have a savior complex, she said, seeing themselves as “saving these people,” while harboring “a disgust and loathing of their own patients,” whom they view as confused and delusional.

Following the release of the Cass Review, Undark spoke with three young adults who are transgender and who support gender-affirming care for youth. Ben Greene, the author of a new book for parents of children who identify as trans, said he had a mastectomy at 19 and began hormones at the age of 21, but wishes he had had access to medical treatment sooner. “Because I didn’t have access to hormone therapy or hormone blockers,” he wrote in an email, “most of my medical transition was reparative — I was and still am working to undo the puberty I never wanted to go through.” A college student named Adrian said that he did receive hormones as a minor. The treatment didn’t just make him happier, he said. It may also have saved his life.

A young woman named Brianna Camp said that she received hormones at age 17. She’s glad that she was able to medically transition, but suggested that there should be a formal system designed for patients who want to learn more about how the medications can affect their bodies. “It’s really difficult to have nuance with these discussions,” she said, “because if you cede any ground — like, the other side doesn’t want trans health care at all.” In a follow-up email, Camp emphasized that the system she envisions should not be “decided by politicians or their cronies.” Most transgender people, she wrote, understand what hormone therapies entail, but “there is a very small minority who maybe aren’t as educated as they should be.”

Before coming to Harvard, Caraballo worked as an attorney on a number of cases involving the rights of LGBTQ people to access medical care. In 2022, she published a paper arguing that court cases in the U.S. routinely draw on anti-transgender experts to give their cause “a veneer of professional credibility.”

Of the individuals and groups involved in this field, she wrote, SEGM is “the most prominent of the pseudo-scientific organizations in the anti-trans space.” Caraballo worries the movement against medical gender interventions in children will lead to diminished access for adults as well, something that has already happened in her home state of Florida and that conservative legislatures in some other states are exploring. She encourages lawyers fighting state restrictions to undermine the credentials of opposing expert witnesses by citing the Daubert standard, a set of principles for assessing the admissibility of scientific evidence in U.S. courtrooms.

Alejandra Caraballo, a clinical instructor at Harvard University’s Cyberlaw Clinic, told Undark that SEGM is “the most prominent of the pseudo-scientific organizations in the anti-trans space.”

Visual: Courtesy of Alejandra Caraballo

Yale’s McNamara said that many judges who have heard the evidence of experts in the field — experts “who actually treat youth with gender dysphoria” — have concluded that views like Malone’s and those of other SEGM members, are “scientifically and medically unsound.”

While SEGM has critiqued the gender-affirmative model of care, Caraballo said they have offered little as an alternative. “That’s the main issue, is that they don’t really follow a scientific method here. Their entire strategy is the climate change model, where it is to undermine and attack the existing science and evidence without really providing any proper evidence of their own for counter view,” she said.

Caraballo said that multiple high-quality studies show the effectiveness of gender-affirming care, but as the evidence continues to build, SEGM’s focus remains on the studies’ limitations. She cited one study that followed 104 young people aged 13 to 20 for a year and found lower rates of depression and a 73 percent lower likelihood of suicidality after gender-affirming care. The authors concluded that treatment could improve young people’s well-being, though they cautioned that the study did not account for the receipt of anti-depressants and other similar drugs, and that it included young people with supportive families, which might not reflect the experience of the broader population. (The study’s findings have been challenged elsewhere.)

Meanwhile, Caraballo described SEGM’s strategy as circular, inserting their views into European policy through experts like Riittakerttu Kaltiala, chief psychiatrist in the department of adolescent psychiatry at Tampere Hospital, Finland, and then using that policy as evidence that the U.S. needs to change course.

“Their entire strategy is the climate change model, where it is to undermine and attack the existing science and evidence without really providing any proper evidence of their own for counter view.”

In 2011, Kaltiala helped establish a pediatric gender clinic in her home country, but came to believe that patients who received treatment were getting worse. In an article she wrote last year for The Free Press, Kaltiala noted that she and colleagues conducted research to better understand why. She has since come to conclude that for many patients, gender-affirming care is the wrong approach.

Kaltiala told Undark that she served as a member of an external advisory group for the Cass Review, but did not conduct any of the research included. And while she was a speaker at SEGM’s fall conference, she said she has no formal affiliation with the group and that her main interest lies in developing and disseminating research.

“I would just ask, ‘What if I was a member of SEGM?’” she added. “What’s the problem?”

She asked whether the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, or WPATH, is also trying to influence the debate. “Quite many activists are members of the WPATH, so why is that not problematized?” In a follow-up email, Kaltiala emphasized that she found the suggestion of bias on her part “absolutely ridiculous.” She said that she has spoken at a WPATH webinar and has also worked with EPATH, or the European Professional Association for Transgender Health. “I am a scientist, and I am interested only in scientific evidence.”

A systematic review, commissioned as part the U.K. report and conducted by researchers at the University of York, identified a different kind of influence in the field of pediatric gender medicine. In analyzing clinical guidelines from organizations across the globe, the authors found that two sets of guidelines — WPATH’s and the Endocrine Society’s — formed the basis for most of the others. The problem, according to the reviewers, is that both guidelines lack transparency and developmental rigor, and they each refer to the other’s content.

In an email, the Endocrine Society defended its guidelines, saying they were developed using a robust process “that adheres to the highest standards of trustworthiness and transparency, as defined by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine).” In February, the Endocrine Society noted that it is in the process of conducting a routine update of its guidelines, which will appear in 2026.

The AAP guidelines also fared poorly in the systematic review. When Undark asked the organization for comment, a spokesperson replied by email: “Caring for transgender adolescents does not look different than any other routine interactions pediatricians have with families in that it starts with a conversation and centers on supporting the patient. Using a patient’s preferred pronouns, counseling patients and their families, discussing appropriate timelines and sequence for a variety of care options, and reviewing the risks and benefits, especially in relation to pubertal and developmental progression, are all elements of gender-affirming care.”

Last year, the AAP stated that it will conduct its own systematic review of the evidence and update its guidelines accordingly. When asked to comment on the U.K.’s approach to treating gender dysphoria in adolescents, the spokesperson said the organization could not “speak to international policies, nor the background and results of other country’s studies.”

Roberto D’Angelo, the Australia-based psychotherapist, suggested that for those who speak publicly about their unease with certain aspects of gender-affirming care, the criticism can feel relentless. He described himself as perpetually misunderstood. “I’m gay myself,” he said. “I have been part of the gender-diverse community for a long time. I think we should embrace gender diversity.”

But in a field beset by passion and conflict, measured discussion can be hard to find.

Caraballo — who has tangled with journalists covering the topic on social media — pointed, for example, to a Congressional hearing last year, in which U.S. Rep. Harriet Hageman, a Wyoming Republican, described gender-affirming care as a “sexual lobotomy.”

Az Hakeem, a U.K. psychiatrist who has collaborated with SEGM, referred to puberty blockers as “chemical castration agents” during an interview with Undark. The term “puberty blockers,” he said, was a euphemism. “Rather than this sanitized ‘puberty blockers,’ it is what it is — it’s a chemical castration,” he said.

Alongside the heated rhetoric, many of SEGM’s critics suspect that the group is working with — and even funded by — conservative Christians and right-wing political operatives. Headlines on trans-activist websites have declared “SEGM Uncovered: Large Anonymous Payments Funding Dodgy Science” or “SEGM Exposed Reloaded: The Shadow Money Behind a Leading Anti-Trans Think Tank.”

Both of these articles were cited in a 2023 analysis published by the nonprofit Southern Poverty Law Center, known in part for its listing and classification of hate groups. The article notes that three anonymous donors contributed more than $50,000 to SEGM through a GoFundMe campaign created by Malone in December of 2019. Additionally, in the 2020-2021 fiscal year, a large part of SEGM’s funding came from the Edward Charles Foundation, a California-based philanthropy.

Undark spoke to one of SEGM’s major donors, who said of the references to the Edward Charles Foundation: “That was probably me.” The donor, a 68-year-old woman from California who asked to remain anonymous because she feared harassment, described herself as a non-religious feminist who had supported Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

According to publicly available accounts, donations to SEGM totaled about $200,000 in 2020. The following year, the group received roughly $793,000. And in 2022, the group received around $229,000.

Az Hakeem, a U.K. psychiatrist who has collaborated with SEGM, referred to puberty blockers as “chemical castration agents” during an interview with Undark.

Malone said SEGM started small but has received thousands of donations of varying amounts from donors who like the group’s work. “Where is this dark money? I’d like to see it,” he joked.

The editor of the SPLC report, R. G. Cravens, told Undark he had no issues with the Edward Charles Foundation or the GoFundMe campaign specifically but felt it was important to shed light on the sources of SEGM’s revenue. “Whenever you’re talking about a group that’s influencing public policy and influencing public opinion, it’s really important that we know who is funding those groups.”

Cravens pointed out that William Malone had co-signed a petition to the FDA expressing concerns about puberty blockers with a member of the American College of Pediatricians, an association of conservative doctors that has made homophobic statements and is designated a hate group by the SPLC.

A transgender activist also published leaked emails indicating SEGM’s involvement in discussions with religious conservatives about legislation to prohibit changing one’s sex on a birth certificate. In an email, Malone shared wording from a 2019 contribution SEGM made to the Department of Health and Human Services urging health care organizations to “maintain a clear distinction between sex and gender” by documenting patients’ “natal or biological sex” in their medical records.

Malone also circulated an article he co-authored for the digital magazine Quillette, in which he declared that “no child is actually born in the wrong body.”

Malone, who describes himself as a classical liberal and not religious, told Undark he is aware that critics sometimes cite his communications as proof that SEGM is “secretly a right-wing Christian puppet.” But such criticism overlooks that fact that SEGM collaborates with professionals who hold a wide range of views on gender medicine, he said, including those who live as transgender adults. “From our inception, SEGM has been pluralistic,” he said.

In a subsequent email, he added that holding Christian beliefs should not undermine a clinician’s credibility. Activists “never seem to mention that President Biden, who has been promoting youth transitions, is also a Christian. So, this ‘purity test’ imposed by activists has nothing to do with religion, and everything to do with selectively attacking those one disagrees with,” he wrote.

Abbruzzese pointed out that the conservatives decided not to draw on SEGM’s statement for the Idaho bill after all. “Ultimately, the group decided to not include it because it did not like SEGM’s use of the terms ‘transgender,’ ‘nonbinary,’ etc.,” she wrote in an email. “Those leading the initiative also decided to distance from SEGM because they did not feel they could trust that SEGM was on ‘their side.’”

Clinicians who speak publicly about their worries regarding the medicalization of care for gender dysphoric youth have cited a range of reasons. SEGM’s president, Roberto D’Angelo, for example, said he went through a period of gender dysphoria himself in his early adolescence. “I didn’t cut it as a boy, I was too girly,” he said. “And now I was moving into adolescence, and I just felt that I would never make it as a man, I would never be adequate. And I was already experiencing teasing, bullying,” he said.

He found that therapy helped, and he currently works with LGBTQ+ people in their teens and early 20s at his practice near Byron Bay, Australia. In his own clinic, a psychotherapeutic approach does not preclude medical transition, he said, but the medical path should not be rushed. Therapy has always been a resource for people in distress, he suggested. He worries about a population of young gay people who are receiving the wrong care.

When he published some papers about the role of psychiatry in authorizing physical treatment for gender dysphoria, someone from SEGM — perhaps William Malone, he recalled — reached out to him. Speaking by Zoom, D’Angelo lamented the fact that psychotherapy has wrongly been conflated with conversion therapy, a harmful practice that attempts to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity. Although D’Angelo does not write the referrals, some of his patients do receive medical treatment to transition, he said. “One of the basic rules of psychotherapy is that we don’t try to influence the patient” to take any particular action.

After his interview, D’Angelo wrote to Undark to elaborate on his views: “What we don’t know is whether the kids in those studies would be doing just as well if they had not received gender affirming interventions, whether they would be worse off, or whether they would even be doing better had they not had those treatments.”

The problem, Abbruzzese and others affiliated with SEGM say, is that clinicians who have concerns about gender-affirming care are hesitant to talk publicly about their worries. Abbruzzese views SEGM as providing momentum to an overdue but inevitable public conversation. “Perhaps by facilitating those connections, it’s happening a bit faster because people are meeting each other and understanding that they’re not alone in their concerns and that it is okay to speak out,” she said, “and in fact, it’s their moral and ethical obligation as physicians to speak out.”

In 2022, SEGM helped organize a conference at Tampere University in Finland, although Abbruzzese stressed that it was not an official SEGM event. Attendees included Dutch clinicians like Thomas Steensma and Annalou de Vries, whose research helped establish the Dutch protocol, on which pediatric gender medicine is based. In 2014, a pioneering Dutch study of 55 adolescents who received puberty blockers, cross-sex hormones, and surgery found that the patients were functioning well in adulthood.

Discussion with the Dutch scholars was a little tricky at times, Abbruzzese said, as some conference attendees were primed for an intense debate. “That was one of our lessons learned is that we need to better manage the discussions,” she said. “If we want people who disagree with us to come, we also have to think through ways how to make room for them to feel safe to express what they believe.”

The problem, Abbruzzese and others affiliated with SEGM say, is that clinicians who have concerns about gender-affirming care are hesitant to talk publicly about their worries.

In October 2023, SEGM held its first official conference in New York, which brought together an array of high-profile speakers, such as Mikael Landén, a psychiatrist and researcher at Sweden’s Karolinska Institute, and Sallie Baxendale, a professor of clinical neuropsychology at University College London. Journalists from Canadian public radio attended, along with then-BBC Newsnight reporter Hannah Barnes, whose bestselling book “Time to Think” chronicled the rise and fall of the Tavistock gender clinic. (“This story remains complex, defying certainty,” wrote a reviewer in The Guardian.)

Erica Anderson, the transgender clinical psychologist, also attended the conference. “I’m actually quite happy to be part of that group,” she said, “and try to contribute to the constructive conversation about what’s going on with gender-questioning youth and what do we know — and more importantly, perhaps, what do we not know.”

Several years ago, Anderson voiced concerns about how the Dutch protocol was being applied in other countries. In the original Dutch studies, teens who medically transitioned met strict criteria, including having family support and no serious psychiatric issues. The criteria were subsequently loosened in other countries setting up gender clinics. At the same time, there was a sharp rise in teens, particularly natal females, seeking care. While the Dutch protocol is sometimes referred to as gender-affirming care, some U.S. practitioners, along with the Cass Review, define the protocol as a separate and stricter mode of treatment.

“If we want people who disagree with us to come, we also have to think through ways how to make room for them to feel safe to express what they believe.”

Critics of the original Dutch studies have pointed to the absence of a control group, and to a study conducted in the U.K. that was unable to replicate the Dutch findings. A 2023 analysis of 12-to-15-year-old patients on puberty blockers found that adolescents’ mental health did not change significantly over the course of treatment. In her Free Press article, Kaltiala suggested “the foundation on which the Dutch protocol was based is crumbling.”

Among those present at SEGM’s New York conference was Gordon Guyatt, a professor at McMaster University in Canada, and a founding figure in evidence-based medicine, a movement that seeks to bring well-designed research into clinical decision-making. Guyatt is among the experts developing systematic reviews sponsored by SEGM on topics including chest-binding and genital tucking, and puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones for people 25 and under.

Guyatt had already voiced concerns about the science underpinning gender-affirming care. When the AAP announced in August 2023 that it would reaffirm its 2018 policy and develop updated guidelines based on its own systematic review of the evidence, Guyatt told The New York Times the organization had put “the cart before the horse.” After he attended the SEGM conference, some of his colleagues warned him that his involvement in the contentious debate could damage his reputation.

Gordon Guyatt a professor and founding figure in evidence-based medicine, is one of many experts developing systematic reviews sponsored by SEGM. In one sense, he said, SEGM has “made up their minds” by taking a position against gender-affirming care until more evidence arrives.

Visual: Courtesy of Gordon Guyatt

During his presentation, Guyatt addressed a key question for gender medicine: Can randomized controlled trials be used to test treatments? RCTs are viewed by most gender-affirming researchers as unethical in teen patients, on the grounds that study participants in the control group would be deprived of beneficial care. Others have said that an RCT would be impractically difficult.

Guyatt sketched out a trial in which one group of patients would go on medical treatment while another transitioned socially but did not receive drugs. The idea that conducting such a trial is unethical is misguided, he said. “We do randomized trials in life-threatening stuff all the time. Because we want to know whether this treatment in life-threatening situations is a good idea or a bad idea. That just strikes me as silly,” he told Undark by Zoom. (The extent to which gender dysphoria is life-threatening is uncertain and hotly-debated.)

But Guyatt also expressed ambivalence about SEGM’s approach, although he said he knows little about the field of gender medicine. As children move through adolescence towards their late teens, he said, their autonomy demands respect. Withholding care entirely, or even limiting it to the context of clinical trials, is not the correct path. As Guyatt sees it, SEGM places a low value on children’s autonomy.

In medicine, Guyatt told Undark, much of clinical practice has a limited evidence base. “That doesn’t mean we don’t do it. So, I’m saying ultimately, it’s a value and preference decision.”

In a written response to Guyatt’s comments, William Malone said that researchers and clinicians have exaggerated the benefits of gender-affirming care while downplaying the harms to such an extent that it’s nearly impossible for young people to give informed consent. He also said that the group is mainly interested in ensuring that evidence is generated before potentially life-altering interventions are used. He insisted that SEGM has not yet taken a position on “how to move from evidence to action.”

Support Undark Magazine

Undark is a non-profit, editorially independent magazine covering the complicated and often fractious intersection of science and society. If you would like to help support our journalism, please consider making a donation. All proceeds go directly to Undark’s editorial fund.

Guyatt suggested that SEGM is trying to have it both ways. “On the one hand, they haven’t made up their minds,” he said. But on the other hand, “they’ve made up their minds” by taking a position against gender-affirming care until more evidence arrives.

Not all evidence-based medicine experts shared Guyatt’s irritation with SEGM. Ivan Florez, who studied under Guyatt at McMaster University, is now editor-in-chief of the journal Clinical and Public Health Guidelines and director of Colombia’s Cochrane group, which focuses on evidence in medicine. When Zhenya Abbruzzese first contacted him to ask if he would undertake research for SEGM, he said, he looked up the group and was initially troubled by the online allegations. After further research, though, he decided their request was worthwhile, and he currently works with SEGM in an individual capacity. “They are like a light in the dark trying to bring the science,” he said. “That’s what I like — science needs to bring some light. And some people don’t like the light.”

Richard Byng, a general practitioner with a focus on mental health who draws on evidence-based methods in his work at the University of Plymouth, pointed out that differences of opinion are the heart of academic debate. It would be surprising if there were no disagreements about care, even among individuals who are involved with SEGM. “I am aware there are differences within nearly all organizations, and we discuss those,” said Byng. That’s how academia works, he said, with scholars “having differences and discussing them and laying down evidence either way.”

On a Saturday in March, protestors gathered around the building of the Royal College of General Practitioners in London. Someone let off a smoke bomb and the number of police at the scene multiplied swiftly. The activists waved the pink, blue, and white transgender pride flag, and carried a banner bearing the words, “Trans rage, trans power, trans liberation.”

The discussion was organized by the Clinical Advisory Network on Sex and Gender (CAN-SG), a British-Irish group of clinicians calling for “greater understanding of the effects of sex and gender in health care.” It is not affiliated with SEGM, but the two groups have worked with some of the same high-profile people, including Byng and Az Hakeem. In addition to venue employees and security, the event was staffed by family practice doctors and other health care workers, volunteering their time.

Inside the building about 160 attendees, mostly clinicians, gathered to discuss the subject of “First do no harm.” The event was a who’s who of individuals critical of gender-affirming care, from the British writer Julie Bindel to the American Jamie Reed, a whistleblower at a Missouri gender clinic whose emails with SEGM and other groups were investigated by the American Civil Liberties Union. Speakers included Kaltiala, who outlined recent trends in Finland; Anna Hutchinson, a clinical psychologist who formerly worked at the Tavistock GIDS clinic; and Sonia Appleby, who won an employee tribunal against the organization that ran youth gender services in the U.K. People affiliated with SEGM, including Abbruzzese and Byng, were also there.

Although youth transgender medical policy is changing in the U.K., views are still polarized, and opposition to such care remains controversial. When the England’s National Health Service, the country’s public health provider, published its new guidance stating that puberty blockers would no longer be routinely prescribed, the LGBTQ+ rights organization Stonewall said it was concerned access to the treatment had been restricted until a research protocol is set up to study their effects. A researcher at Oxford Brookes University described the Cass Review as “an example of cis-supremacy.”

Outside the U.K., Ada Cheung, an endocrinologist at the University of Melbourne who serves transgender patients, said she was extremely worried that young people might have a harder time accessing care as a result of the Cass Review. There is “substantial observational evidence” showing that puberty blockers improve young people’s well-being, she wrote to Undark in an email.

Cheung pointed to a Dutch study by Steensma, de Vries, and colleagues, which was the only study out of 50 to be described as high-quality in a systematic review of puberty blockers commissioned as part of the Cass Review. The study tracked adolescents who visited the researchers’ clinic from 2012 to 2015. Prior to treatment, the transgender patients had worse psychological well-being than their cis-gender peers. After starting puberty suppression, they experienced similar or better psychological well-being. The study authors noted that “the small amount of scientific evidence” showing that puberty blockers are safe and effective mainly comes from the Netherlands, which follows a strict protocol.

SEGM had “somewhat unexpectedly become influential — even unexpectedly to us.”

At the CAN-SG conference in London, one of the group’s co-chairs, Stella Kingett, a psychiatrist, said it was time for professional organizations to engage with the evidence, even if it led to social censure. “The reality is that people will always be tempted to avoid difficult conversations. So, we will have to keep bringing it up,” Kingett said.

That’s what SEGM sees itself doing. At 30 Euston Square, the closing plenary ended to warm applause and some laughter, as Kingett informed the audience the protestors had dispersed and it was safe to leave. In the coffee area outside the main hall, Abbruzzese spoke to Undark while Byng and others waited nearby. Abbruzzese said the group only sought to “engage with our critics directly,” and she disputed the notion that SEGM was religious or anti-LGBTQ. Many of the clinicians involved, she said, are gay themselves, or have trans family members.

The accusations are a sign of the group’s rising influence, Abbruzzese said, adding that SEGM had “somewhat unexpectedly become influential — even unexpectedly to us.”

UPDATE: This piece has been updated to clarify that in the U.K., new prescriptions for puberty blockers are no longer available through the publicly funded National Health Service for people under 18 specifically for the treatment of gender dysphoria. The medications remain available to treat early puberty and other conditions. An update has also been made to note that Florida has restricted access to medical interventions for transgender adults. The piece also previously described Briana Last as a clinical psychologist at Stony Brook University. She is a faculty member in the university’s psychology department.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

..they talk about trans people but never to them. the only ones that are pulled up there are detrans people (some of those retransitioned btw) but never once do these critical people ever talk to the hundreds of thousands of happy trans people. but they talk to “happy trans people are a problem for a sane world” helen joice at all.

or hanna barnes book based on an inquiry that she and her bbc colleague did. easy to say “people have concern see the inquiry” if you badger a clinic for an inquiry but hide that.

and a lot of the segm people curiously had trans kids that cut off contact once turned 18

i wonder why

i wonder why

curious. ust be coincidence

Thanks to Frieda Klotz for this well-balanced, highly informative and illuminating article. Science has always been about debate and evidence, and if either are stifled, we all suffer.

Thanks for this article. When an insider such as Dr Marci Bowers President- elect (former), World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) expresses concern there is certainty that impacts are indeed severe. Bowers stated in a WPATH online event: “An observation that I have had is that every single child or adolescent who is truly blocked at Tanner stage two has never experienced orgasm.” Bowers continued “I know that from my work with female genital mutilation survivors, that that the lack of being able to be intimate with a partner is very important.”

https://x.com/GendertheHun/status/1521158590920335360?t=2Y_WqvddruDAWBykl6Vamg

Detransitioners’ reports also show that there is little “gate-keeping” before mastectomies and even genital surgeries are being carried out. I am a historian of medicine and sexuality who’s been following this issue. The history of LGB identity suggests the experience of previous generations is not an accurate guide as to whether current children’s or young people’s identity is fixed. Numbers may be small but the consequences of getting it wrong are exclusion from from full adult experience. Trans identifying children require evidence-based medicine and for that we must have open and transparent debate.