Building Durable Basketball Players From the Ground Up (Way Up)

The NBA’s tallest rookie is 7 feet 4 inches tall with an 8-foot wingspan, but last year, a series of video clips highlighted his surprisingly nimble, and often shoeless, feet. In one clip, he’s pressing knees and ankles together while wiggling his toes and hopping forward. In another, he’s bear crawling along the baseline. And in yet another, his right heel and left toes are gliding in opposite directions, gym music pounding in the background, as he eases into the splits.

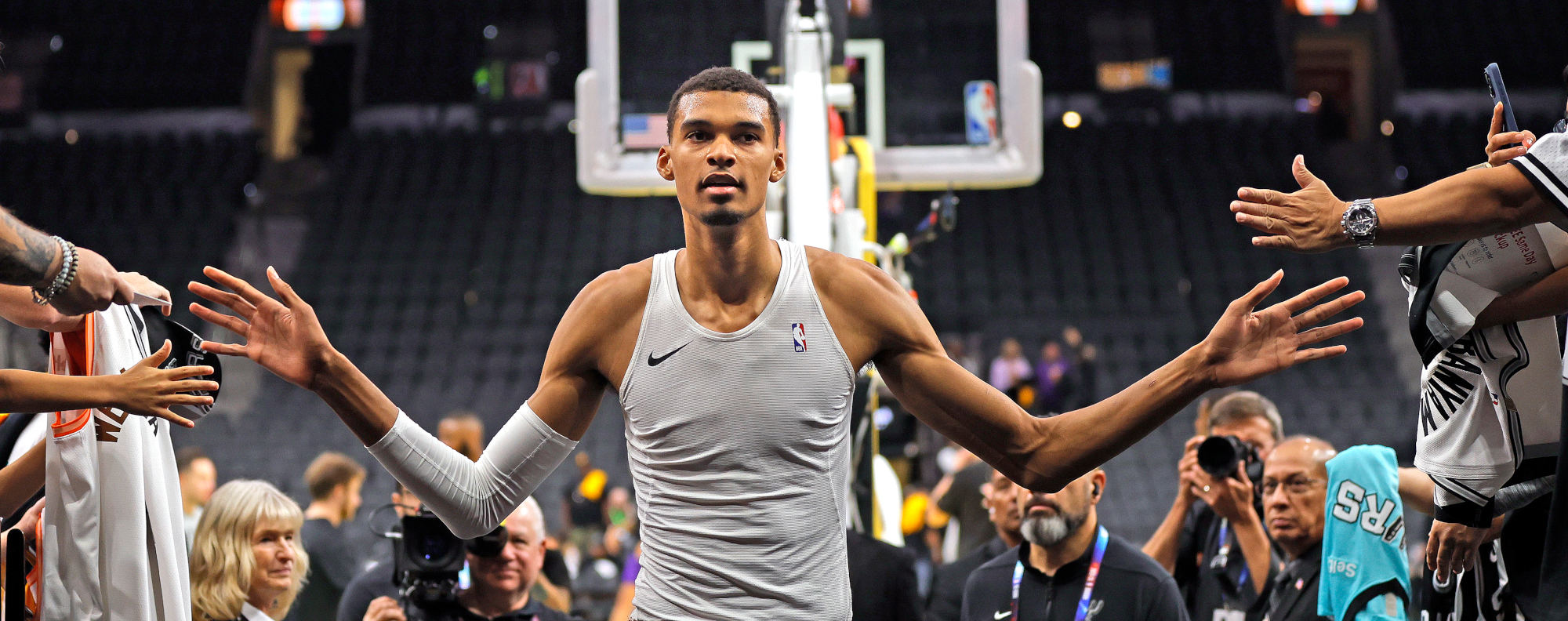

Victor Wembanyama (pronounced wem-ben-YAH-muh), was selected first in last June’s NBA draft at the age of 19. By then, he had played four years of professional basketball in his native France. With a preternatural blend of size, athleticism, and skill, Wembanyama is routinely described as a generational talent. And if the toe-exercise videos are any indication, his trainers appear determined to protect that talent: Sports medicine experts say that long limbs and feet — Wembanyama’s shoe size is 20.5 — confer potential physical vulnerabilities.

Leg, arm, and foot bones all function like levers, and the longer they are, the more force is needed to stabilize them. Tall athletes may find it harder to control their movement as they land from a jump or quickly shift direction. Seven-footers, of course, aren’t the only athletes who get hurt while playing. Across the NBA, injuries are on the rise, with knee, ankle, and foot problems leading the way. Anecdotally, physicians and trainers also report seeing children, some as young as 10 years old, with severe sports-related injuries and chronic wear-and-tear that was once seen mainly in adults.

All of this has fueled a small but growing body of scientific research into basketball and other sports-related injuries. In biomechanics laboratories, experts are creating detailed assessments of how players move on the court. Epidemiologists are poring over reams of data. And NBA teams have been experimenting with new approaches for player safety, including an emphasis on load management, which seeks to optimize an athlete’s ratio of stress to rest.

Much of this science is still unsettled, and there is no foolproof method for injury prevention. But experts who spoke with Undark said there is a solid evidence base for specific warm-up programs, stretches, and exercises that reduce injuries. The findings have not been fully disseminated and implemented. Yet, there’s clearly interest in the topic.

Wembanyama’s barefoot calisthenics have inspired explanatory videos with titles like “Victor Wembanyama’s Weird Toe Workout EXPLAINED!” as well as comments and replies asserting that such exercises could have benefitted previous generations of tall players. “This is smart they’re trying to keep his feet healthy,” wrote a New York Knicks superfan on X, formerly known as Twitter. “[Too] many big men have gone down with foot injuries.”

Danny Seidman, a Michigan-based sports medicine physician (and self-described NBA fanatic), said he’s glad the videos went viral. They got people talking about injury prevention, which has come a long way over the past few decades. “It’s sad for me to see previous athletes in their 50s and 60s who are limping around or hunched over,” said Seidman. “We think we can avoid those sorts of things now.”

Basketball players are most likely to get hurt when they change directions, said Marcus Elliott, the founder and director of Peak Performance Project, or P3, a company that provides biomechanical assessments to elite youth and professional athletes. That directional change can be lateral, as when an athlete is guarding a player who is running left and then suddenly switches right. Or the change can be vertical, as when an athlete lands from a jump. Both movements require what Elliott called “braking power.”

When an athlete brakes, key muscles lengthen as they activate, performing what’s called an eccentric contraction. Consider what happens when squatting, said Elliott: The large muscles at the front of the thigh, the quadriceps, stretch. Ideally, this is what happens when a player lands from a jump.

P3’s database includes information about 41 7-footers, all professionals from the NBA and abroad. Compared with shorter NBA players, these especially tall athletes produce about 15 percent less relative force when performing braking movements, which means they’re not as good at slowing down. “Picture a big, big vehicle like an Escalade, but with a Honda brake,” said Elliott. “That’s inherently a more dangerous system.”

Injuries are not new to the NBA, but they’ve been rising in recent years, and the league isn’t quite sure why. Some have pointed to the so-called pace-and-space revolution, popularized in the mid-aughts. This style of basketball features a breakneck pace, as well as relentless shooting from behind the 3-point line, which requires defenses to cover more floor space.

Might today’s players benefit from more rest? One of the most studied and debated approaches to handling injury has been the concept of load management, which gained traction in elite settings like the NBA throughout the 2010s. At its core, load management rests on the theory that there’s a certain threshold, or load, that every player can tolerate. The question for players and their trainers, said Seidman, is “how do we stress players to the point where they can continue to grow and improve but not pass that point where they’re predisposed to injury?”

In the NBA, load management has translated to having healthy star players sit out some of the regular season’s 82 games, with the goal of keeping them injury-free for the playoffs. This practice has, at times, pitted teams against the league office. In 2012, San Antonio Spurs’ coach Gregg Popovich rested four of the Spurs’ best players during a nationally televised game. The NBA commissioner promptly fined the team $250,000 for “resting players in a manner contrary to the best interests of the NBA.”

“Picture a big, big vehicle like an Escalade, but with a Honda brake. That’s inherently a more dangerous system.”

That was hardly the end of things, as many within the NBA believe that the strategy reduces injuries and contributes to peak performance during the playoffs. The evidence, however, is not clear-cut. A 2022 paper compared healthy players who sat out with similar players who did not. From 2016 to 2021, there was an upward trend in the number of times healthy players missed games, yet the analysis found that these extra rest days did not correlate with better playoff performance. These findings were in line with a smaller study conducted in 2017.

The NBA recently released a formal report, which found that over a 10-year period, there was no relationship between injury risk and missing games for rest.

The concept of rest may be more complicated than simply looking at a single variable and its effect on the post-season, said Sean Pradhan and Travis Miller, co-authors of the 2022 paper and professors at Menlo College in California. It’s possible, for example, that resting a game might have a short-term effect, allowing the player to perform better in the regular season, Miller said. “To me at least, that seems like a reasonable reason to rest.”

Lorena Torres Ronda, a sports scientist who has worked with the San Antonio Spurs and the Philadelphia 76ers and who co-authored a paper on load management, said that the concept may have tilted too much toward rest. Some people interpreted load management to mean “sitting players, resting the players, being very careful with the players,” she said. Recovery, however, is just one piece of the puzzle. The unanswered question is precisely how far a player can safely push themselves without getting hurt. “I don’t have the answer,” she said.

This uncertainty means fans will have to wait and see how well the 210-pound Wembanyama holds up in the regular season.

So far, he ranks among the league’s best rookies, but he had a rocky December. He sat out with hip tightness on the 1st, and then on the 11th, he rolled his right ankle to a cringe-inducing angle. Though he got right up and continued playing, he missed a game on the 19th due to soreness in the same ankle, which he rolled again four days later, when he stepped on a ball boy’s foot during a pre-game warmup.

Wembanyama sat out again on the 29th, and Popovich — now in his 28th year as the Spurs’ coach — announced that, for the near future, the spindly rookie would have his minutes restricted and would not play in back-to-back games, in order to prevent further injury.

Professional basketball players aren’t the only athletes who need to find the right balance between physical stress and rest. That balance is important for young people, too, said the NBA’s director of sports medicine, John DiFiori. Evidence suggests that injuries may be underreported in youth sports, where the focus tends to be on acute injuries — ankle sprains, for example, or torn ligaments — rather than on chronic overuse injuries, which start slowly and get worse over time. Such injuries may ultimately derail an athlete’s career or lead to pain in adulthood.

The problem may be worsening. From 2010 to 2019, youth sport participation patterns drastically changed, according to a paper co-authored by DiFiori and published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. “The primary focus of youth sports has shifted from one of participation, fun and fitness, to one increasingly centered on training and performance,” wrote the authors. Young people were specializing in a single sport at earlier ages.

Evidence suggests that injuries may be underreported in youth sports, where the focus tends to be on acute injuries — ankle sprains, for example — rather than on chronic overuse injuries.

There were real incentives for kids to pour their energy into early achievement: One was college scholarships. More recently, a select few college athletes now earn up to eight figures through the NCAA’s new policy allowing student-athletes to make money off their “name, image, and likeness.” (Among those said to be earning more than $1 million are Bronny James, a University of Southern California basketball player and son of LeBron James, as well as Olivia Dunne, a Louisiana State University gymnast whose expansive list of brand deals includes Vuori, American Eagle, Forever 21, and Motorola.)

The potential for overuse injury is especially high in athletes who perform a limited range of motions, said DiFiori. For example, in baseball, pitchers are more likely to develop an injury than field players who aren’t stressing “the same joints, ligaments, and tendons over and over and over again.” In the clinic, he sometimes sees pitchers who are not yet in high school. With them, he discusses the importance not just of treating the injury, but of reassessing their training. Sometimes he tells parents, “Look, you can’t make your child an elite athlete at this age for this sport,” he said, “but you can ruin their career now if you don’t take care of this properly.”

In 2018, the NBA and the national governing body for basketball in the United States, USA Basketball, developed youth guidelines that draw on the best available evidence. Among the recommendations are not specializing until age 14. At that point, players should get at least one day of rest each week while spending multiple months per year away from organized basketball.

It’s unclear how many people are listening.

In 2021, DiFiori and colleagues published a study that surveyed nearly 800 male and female teenage basketball players. Almost half reported playing more than 50 games over the past year, and more than a third said they specialized before age 11. Nearly three-quarters reported less than one month away from organized basketball within the past year.

Perhaps most troubling: In a subset of 426 youth players, nearly half reported missing a least one month of basketball due to an injury and 17 percent reported having surgery for a basketball-related injury.

The survey offers a glimpse of load management, or lack thereof, in youth sports. More research is needed, though, to better understand the issue, said DiFiori. He pointed to a 2020 study funded by the NBA and GE Healthcare as a good example.

That study tracked more than 500 male and female players through one high school or club season in Canada. The authors defined injury as any basketball-related physical complaint, including pain, achiness, joint instability, and stiffness. “We found out that injuries in youth basketball can be as high as 14 injuries per 1,000 player hours,” said Oluwatoyosi Owoeye, an author of the paper and the director of the Translational Sports Injury Prevention Lab at Saint Louis University. “And that’s huge.”

Owoeye thinks more should be done to mitigate these problems. Delaying specialization could help, he said. But the intervention with the greatest evidence base seeks to improve biomechanics. It’s called neuromuscular training.

Neuromuscular training helps the body understand which body parts should activate first when moving, said Seidman. Imagine reaching up to grab a rebound: Ideally, the muscles around the shoulder joint move first and then, when the arm is high enough, the muscles around the wing bone, or scapula, start to engage as well. “If you do that motion rapidly and the proper muscles are not engaging in the proper order, you get abnormalities in your movement,” said Seidman. This can lead to an injury or cause pain.

In such a case, a trainer might stand behind the player with a hand on the player’s right scapula. As the player raises their right arm, the trainer applies gentle pressure on the scapula until the player’s shoulder joint is at about 90 degrees. The trainer then releases the player’s scapula so that the surrounding muscles can engage. During this process, “your brain tells your body, I want my shoulder muscles to lift first,” said Seidman. With enough repetition, the muscles will automatically engage in the proper sequence.

Owoeye is currently running a study that aims to teach Missouri coaches why and how to implement five- to 10-minute neuromuscular warm-ups, which can reduce acute and overuse injuries, he said, in some cases up to 60 percent.

The evidence base is strong, he added. “We just need the coaches to start doing these programs.”

The NBA is interested in biomechanics, too. Roughly two-thirds of current players have been assessed by P3, said Elliott. The company uses high-speed cameras, in-floor force plates, and proprietary software to collect data from athletes as they perform sports-specific movements, such as jumping and sliding right and left. The end result is a detailed assessment of how each player moves on the court.

Among other things, the assessment can reveal how much certain bones rotate when a player lands from a jump, said Elliott. If the bones of the foot or leg rotate too much, an athlete is more likely to incur an injury. Exceptionally tall athletes with long feet may be especially at risk, he added: “If you have a rotation across your foot and you wear a size 11, that’s one thing. But if you wear a size 23, it’s a whole different level of forces” that get transferred to the ankle.

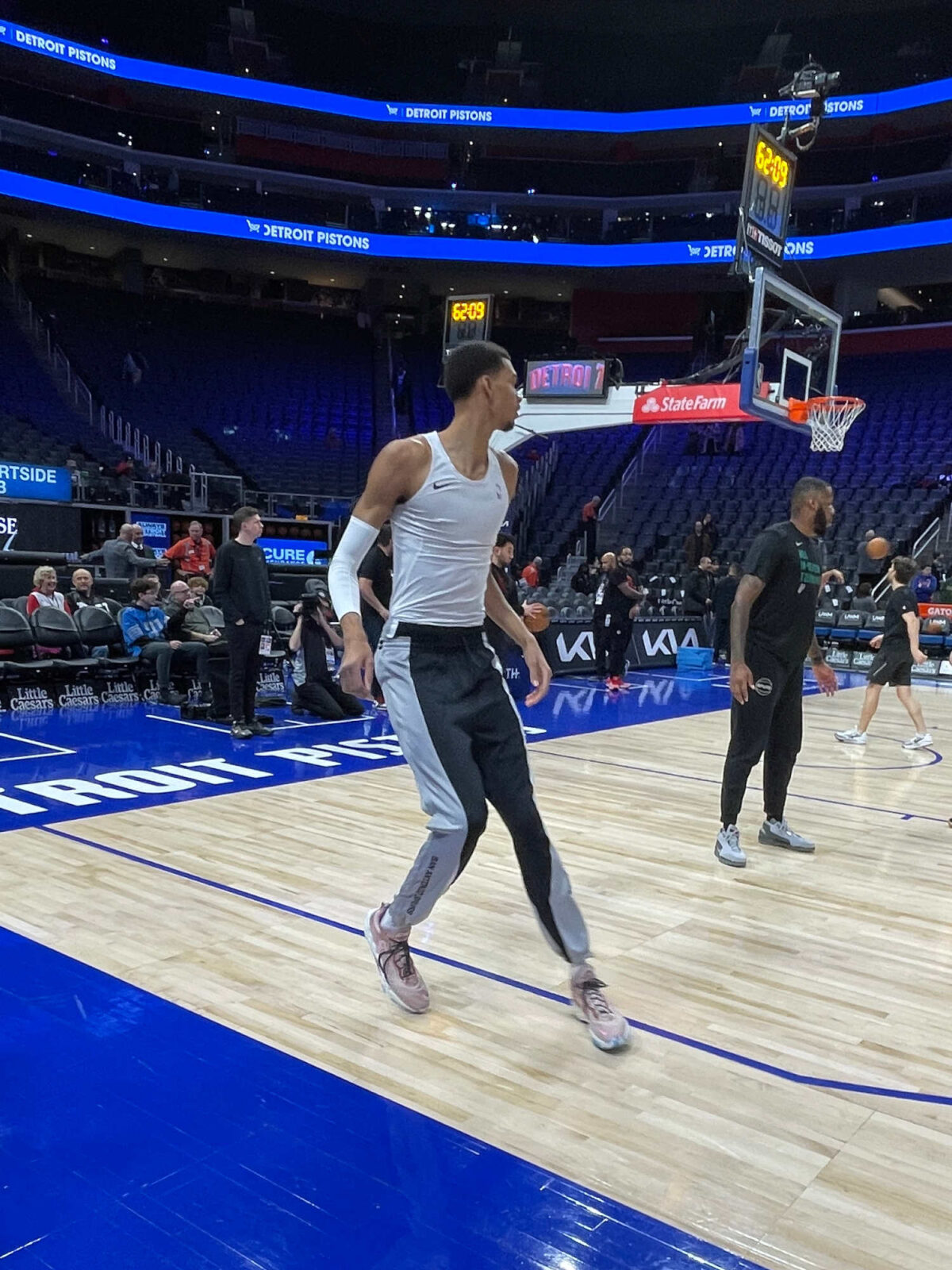

Wembenyama warms up before a January game in Detroit, clad in his pink Nikes. Basketball players tend to be hard on their feet because they do a lot of landing and cutting while their feet often remain passive inside the shoe.

Visual: Sara Talpos for Undark

Players can be trained to modify their movements. For example, landing with the toes pointing upward minimizes the amount of rotation across the foot, said Elliott. The big toe is especially crucial because it initiates most movements of the foot. But of all the professional athletes that P3 sees, basketball players tend to have the worst feet, said Elliott. That’s because they do a lot of landing and cutting while their feet frequently remain passive inside the shoe, even as they’re shaken and smashed.

Flexibility is important, too. Athletes need mobility to adequately flex when landing from a jump or changing directions, said Elliott. “That’s particularly so in the bigs,” he added, referring to 7-footers, who on average have less ankle and hip mobility.

Erhan Kara, a sports scientist at Tekirdag Namik Kemal University in Turkey, pointed out other challenges that extremely tall players face: Their center of gravity is higher, which means they are potentially less stable, he wrote in an email. Additionally, rapid growth during adolescence can lead to muscle imbalances that increase the risk of injury.

The Spurs declined to comment on Wembanyama’s training regimen, but Seidman said that the 7-footer’s unusual exercises may indeed be fostering optimal biomechanics.

The toe wiggling, seen in the video clip shared last year, appears to be a form of dynamic stretching, said Seidman. This kind of stretching entails actively moving the joints, often through sports-specific motions, as part of a warm-up. Seidman cited football player Dak Prescott’s pre-game hip exercises, or hip whip, as an example. “And so when he goes to throw a football and he twists his hip quickly, the muscle will know what to do because it’s been doing that already,” said Seidman. This reduces his injury risk.

As for the bear crawl, Seidman said it strengthens the core, which can help with overall stability. Doing it in bare feet will activate tiny foot muscles, known as intrinsic muscles, that are harder to access when wearing shoes.

“Look, you can’t make your child an elite athlete at this age for this sport,” DiFiori said. “But you can ruin their career now if you don’t take care of this properly.”

An hour before the Spurs’ January game in Detroit, Wembanyama’s famous feet were clad in pink Nikes with purple laces as he warmed up. A small group of fans clustered courtside, watching as he ran through a series of dribbling drills, post-up moves, free throws, and casual dunks — his hands touching down from well above the rim. (He would use similar moves during the game, notching his first NBA triple-double as the Spurs routed the Pistons, whose leading scorer was out with a left knee injury.)

Heading to the locker room, Wembanyama stopped for a few pictures, hands on his hips and smiling. A 13-year-old named Levi stood nearby. What does he like about the league’s newest star? “The fact that he can be that tall, and he can drain threes and just drive into the hoop.”

“There has never been a player in the league like him,” said a Pistons’ broadcaster shortly before tipoff.

“My hope,” he added, “is that Victor Wembanyama stays healthy — for the long run.”