When Doctors Need Doctors: Lowering the Barriers to Seeking Help

In October 2022, Marc Laruelle, a leading schizophrenia researcher who has held prestigious professorships at both Columbia University and Yale University, pleaded guilty to one count of illegally distributing oxycodone, amphetamines, and benzodiazepines to numerous patients between 2016 and 2021. In an interview conducted in March in his lawyer’s office in White Plains, New York, Laruelle admitted he was fully aware that his patients would in turn sell those drugs on the street. “What I did was horrible,” Laruelle said. “People could have gotten killed. It’s painful to accept.”

Two weeks later, the psychiatrist, now 66, was sent to FMC Devens, a federal prison 40 miles west of Boston, to begin serving his four-year sentence.

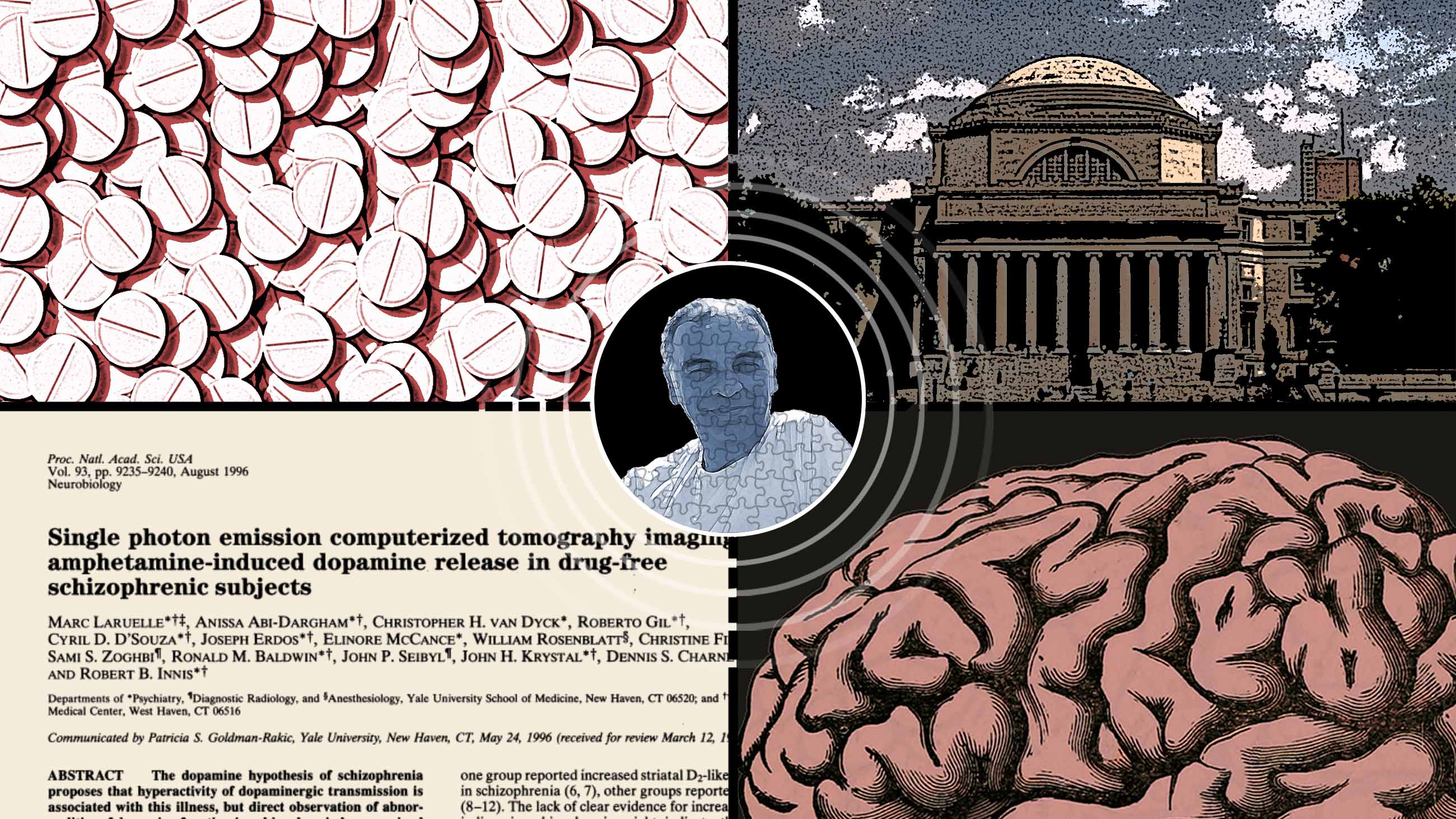

It was a precipitous fall for a celebrated doctor. In 1996, just a few years after arriving from his native Belgium to assume a position as an assistant professor at Yale, Laruelle was the lead author of a landmark schizophrenia paper co-written with numerous colleagues from his department. Using what was a new brain imaging technique at the time, this study showed a vast difference between the brains of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and those of healthy controls. When administered amphetamines, the subjects with schizophrenia exhibited both higher levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, and more psychotic symptoms than the control subjects.

Laruelle received lofty accolades for this work, and Jeffrey Lieberman, the former chair of psychiatry at Columbia, has called it “the first direct evidence in support of the dopamine theory of schizophrenia.”

Laruelle was immediately recruited by Columbia and the affiliated New York State Psychiatric Institute, where he continued to blaze trails in the fields of both schizophrenia research and brain imaging. Between 1997 and the end of 2005, when he left Columbia to lead the clinical imaging center of the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline, he co-authored roughly 80 peer-reviewed articles in leading medical and psychiatric journals.

Beneath the veneer of a high-flying psychiatrist and academic, however, trouble was brewing: Laruelle now says that he’d begun struggling with mental illness as far back as 2001 — when he says he became hypomanic. This mild form of mania is often associated with high levels of productivity. “In my last few years at Columbia, I was pulling in about $5 million a year in grants, and publishing many papers,” he said.

But by 2014, he had developed full-blown mania. Though he said he was putting in 80- or 90-hour work weeks, he was sleeping just two or three hours each night, and his behavior became increasingly erratic. He began visiting clubs and pursuing relationships with exotic dancers. He also splurged on fancy cars and vacations which he couldn’t really afford. “I felt on top of the world — like a rock star — and didn’t think there were any consequences to doing whatever I wanted,” he recalled.

In this severely manic phase of his bipolar illness, which lasted until his arrest, after Laruelle had quit all of his prestigious appointments, he was reduced to bouncing from one temporary job to another. He was using cocaine and cannabis, and he could often be found working as an attending psychiatrist at public hospitals. In addition, Laruelle says, he opened a small private clinic where his illegal drug distribution to numerous patients unfolded. His prison sentence caps what Laruelle and his supporters describe as nearly a decade of mostly untreated bipolar disorder, typified by numerous psychological symptoms, including grandiosity, extreme irritability, recklessness, and racing thoughts.

The veracity of Laruelle’s long-term account is impossible to adjudicate, and a good-faith assessment of his rise and fall might simply settle on that of a self-absorbed high-performer who earned an overdue comeuppance. But the accounts of people who have known Laruelle, including the psychiatrist who ultimately treated him for bipolar disorder, suggest a much more complicated narrative — one featuring a doctor who devoted his life to studying and treating mental illness, but whose own deteriorating mental health remained invisible and unchecked.

It’s also a narrative that a growing number of physicians say is both very real and too frequently hushed into whispers across academia and the wider health care profession: Much like anyone, they say, doctors can be afflicted with one form of mental illness or another. But within the dynamics specific to the practice of medicine, where licensure and professional stature are necessary coins of the realm, where long hours and heavy caseloads are common, and where young doctors are acutely trained to focus on their patients and not on themselves, emotional distress and mental illness can often go unacknowledged and unaddressed.

“For too long there has been a lack of attention paid, within the medical profession, to the wellness of its own members,” said Humayan Chaudhry, a clinical associate professor of medicine at The George Washington University, who currently serves as president and CEO of the Federation of State Medical Boards. In 2018, the group released a report that recommended that all state medical boards review their licensing applications and evaluate whether it is necessary to include questions about mental health treatment. But the issue isn’t just with licensing boards, Chaudhry added. “We are now focusing on getting health systems, hospitals, and insurance companies to be more supportive of physicians who take care of their own mental health needs.”

For Laruelle, who began formal treatment for his mental illness only in 2021, such support might have made a difference. “I am now back to the way I was now before I became ill,” he said before departing to serve out his sentence. “What I learned is that if you have mania, you have to get treatment. Otherwise it will destroy you. I have lost everything.”

While it is rare for a psychiatrist or any other type of medical doctor to experience so many years of untreated bipolar disorder — which can be life threatening — it is not uncommon for doctors to struggle with a less severe mental illness such as depression for limited periods of time. As noted in a review article published in The Lancet in 2021, surveys conducted over the last decade suggest that physicians tend to experience about the same rate of common mental health disorders as people who work in other occupations. And as is true in the general population, the two most common psychiatric disorders found among physicians are depression and anxiety, with several studies reporting that about one quarter of physicians likely suffer from each of these conditions.

Medical students tend to have fewer psychiatric disorders than people in other walks of life, but tend to catch up with — and surpass — the rest of the population by the time they finish their residency, notes Thomas Schwenk, a former dean of the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine, who has published some of the earliest comprehensive studies on the mental health of medical students. “The stress of the job impairs their emotional health,” he said. And though doctors are only somewhat more likely to be depressed than the average person “their risk of suicide is higher.”

According to data compiled by the National Institute of Mental Health, physicians are about 10 times more likely to have thoughts of committing suicide or to attempt suicide than adults in the general population. And rate of suicide among physicians is also elevated — about 1.5 to 2.5 times higher than the general population, Schwenk wrote in an email to Undark.

Schwenk and other experts contend that a key reason for the higher suicide rate is that many doctors are reluctant to access mental health care. As Ronald Epstein, a co-author of the 2021 article in The Lancet and a professor of family medicine and oncology at the University of Rochester, put it: “Medical training requires putting in 80 hours per week, and doctors are used to neglecting their own health. Resilience is part of the problem.”

Epstein says psychiatrists are no more likely to seek help for mental disorders than other doctors. “This lack of self-awareness applies to doctors in most specialties,” he said, pointing out that he has known family doctors who have avoided getting treatment for their own heart problems. “The human capacity for denial is nearly infinite.”

Doctors also tend to avoid getting treatment for their psychiatric problems out of a fear of losing their license. In a survey of about 2,000 female physicians from all 50 states titled “I would never want to have a mental health diagnosis on my record,” published in the journal General Hospital Psychiatry in 2016, Katherine Gold, a professor of family medicine at the University of Michigan, reported that only 6 percent of the doctors in her sample who had either received a formal mental health diagnosis or gotten treatment notified the state licensing board of their condition.

Remarkably, nearly 50 percent of the female physicians surveyed believed that they met the criteria for a mental health diagnosis, but had not sought treatment. The three most common reasons given were: “Felt I could get through without help” (68 percent), “Didn’t have the time” (52 percent), and “Getting a diagnosis would be embarrassing or shameful” (45 percent).

Gold believes that state licensing boards should stop asking physicians about their mental health. “This just reinforces stigma and inhibits treatment,” she said. And in a follow-up letter to the editor published in 2020 in General Hospital Psychiatry, she pointed out that the punitive approach taken by some physician health programs, which are recommended by state licensing boards, poses a major risk for physician suicide.

Eliminating these mental health question from licensure and credentialing applications has been a core part of the mission of the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation, which was founded in 2020 soon after the suicide of Lorna Breen, the emergency room director at NewYork-Presbyterian’s Allen Hospital. According to this nonprofit, which advocates for the well-being of health care workers, as of May 2023, 21 states have followed its recommendations.

Gold argues that patients would be better served if physicians did not have to worry about losing their jobs for getting treatment for common mental health issues. “There is no data suggesting that physicians with a diagnosable mental illness provide worse care,” she said. “It’s usually just the physician who suffers. In our training, we are taught that the patient always comes first, and physicians are very good at masking what is going inside.”

In 2018, the American Medical Association announced a policy that “encourages state licensing boards to require disclosure of physical or mental health conditions only when a physician is suffering from any condition that currently impairs his/her judgment or that would otherwise adversely affect his/her ability to practice medicine in a competent, ethical, and professional manner, or when the physician presents a public health danger.” And the AMA is opposed to questions that ask about a past mental health diagnosis or treatment.

Even when doctors suffer from a mental health disorder, they can typically provide good care to their patients. “I have treated doctors with low-esteem who were miserable in their everyday lives, but who were modern-day saints and did remarkable work — say, with end-stage cancer patients,” said Peter Kramer, a professor emeritus of psychiatry at Brown University and the author of the 1993 bestseller “Listening to Prozac.” “A lot of good things get done by people with mental illness.”

Susan T. Mahler, a psychiatrist with a private practice in western Massachusetts, who has written about her own 20-year battle with depression, which began while she was in medical school in the mid-1990s, says her history has made her more sensitive to the plight of her patients. “When I hear a patient say something like, ‘I can’t stand to be awake,’ I realize right away that this is a sign of a really deep depression because I remember that feeling,” she said.

Mahler, who was hospitalized for depression on a few occasions but has been free of significant symptoms for about five years, said that overall, her supervisors were incredibly compassionate about her illness. But still, “I think people in medicine have a hard time when one of their own is sick,” Mahler said.

Some younger psychiatrists who have been open about their psychiatric problems report a welcoming environment in the workplace. Jessi Gold, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis who specializes in the mental health treatment of health care workers, began receiving psychiatric treatment — an antidepressant plus weekly therapy — during her undergraduate days about 15 years ago. Gold stresses that her ongoing treatment has been very helpful in keeping her depression at bay since around 2009.

A couple of years ago, she decided to go public about her use of medication to cope with her depression. “While I had mentioned being in therapy before, I realized that I had been reluctant to admit to taking an antidepressant,” she said. “But the feedback has been very positive. Many people have told me that it is nice to hear this stuff. Perhaps that’s because my situation is pretty common — it’s similar to what a lot of my patients are going through.”

Gold believes that the culture of medicine needs to evolve. “Doctors are trained to compartmentalize,” she stressed. “They learn it as a skill. Sometimes they see someone die and then have to go to lunch. But when they rely on this too much, they can get into trouble. Most of the health care workers I treat are not making errors, but worry that they could eventually get so overwhelmed that they could hurt someone.” But as Gold emphasizes, her patients typically stop working when they notice that they are becoming acutely distressed.

Gold contends that medical schools should require some individual psychotherapy as part of their curriculum: “All doctors could benefit from knowing how to take better care of themselves.”

Chase Anderson, an assistant professor of psychiatry at University of California San Francisco, also went public a few years ago about his struggles with depression and suicidal thoughts that have plagued him since adolescence. “Coming out about my history with depression was terrifying,” he said. “But I figured that other doctors would see this and the world would be a little safer for them.”

Now 34, Anderson attributes his feelings of despair to both a genetic predisposition and what he calls “minority stress” — his status as a gay, Black man. He notes that after particularly severe symptoms during his freshman year at MIT, he managed to find a group of supportive friends who could validate his experiences. His symptoms continually improved during his undergraduate years and he moved into a period of remission, he said. But while attending medical school at Northwestern University he found himself falling into deep depressions again. “I was class president, but I heard lots of racist things” and began having nightmares, he said. Long-term therapy plus antidepressant medication enabled him to get through medical school and his residency at Harvard without being hospitalized.

Anderson adds that he can still get severely depressed, but the “flash” episodes that he experiences are not as intense as they used to be. To ensure that his illness doesn’t impact his patients, he maintains a robust support network of friends and colleagues and uses other tools like medication and weekly therapy. “My patient care is paramount to me.”

At Columbia, Laruelle frequently collaborated on research projects with his wife, psychiatrist Anissa Abi-Dargham, who he now says could see his illness emerging. In 2003 he left her. (In response to a request for an interview, Abi-Dargham, who was married to Laruelle from 1992 to 2005 and is now a professor and chair of psychiatry and behavioral health at Stony Brook University, declined to comment.)

After a few years at GlaxoSmithKline, Laruelle returned to Yale in the fall of 2011. In an email, John Krystal, the current chair of Yale’s psychiatry department, who co-wrote several of Laruelle’s early papers and recruited him to return to the university, called Laruelle “one of the most brilliant, exacting, and focused scientists that I have ever met. We were colleagues, collaborators, and friends.”

But after six months, Laruelle gave up his cushy professorship at the Yale Medical School. “Leaving Yale wasn’t a wise decision,” he said. “Who in his right mind quits a tenured position?” Yet Laruelle also stressed that at the time he had a deep desire to go back into industry where he could help develop drugs, rather than stay in academia.

Even though Laruelle has treated many patients with bipolar disorder over the years, he was unable to turn his diagnostic lens on himself. “Until the day I was arrested in the fall of 2021, I never thought I was manic,” he added. “I guess the DEA agent who arrested me saved my life.”

In 2020, a bout with long Covid brought Laruelle into the office of Siddhartha Nadkarni, a New York University psychiatrist who ended up treating his bipolar disorder. “I was depressed and in a brain fog and couldn’t concentrate,” he said. At that time, Laruelle was put on an antidepressant, which, he claims, ended up making his mania worse.

After his arrest, he went back to Nadkarni for weekly psychotherapy, and that’s when he began taking a mood stabilizer, Lamictal — a drug originally designed to treat epilepsy, which he himself had helped to market for the treatment of bipolar disorder during his stint at GlaxoSmithKline.

In the last few years before his arrest, Laruelle maintained a private practice in White Plains where he specialized in psychopharmacology. “I was working long hours and would see as many as 600 patients a year.” After the interview with Undark, he provided a couple of dozen letters from recent patients — which his legal team had previously solicited to prepare for his legal case — attesting to how the medications he prescribed turned their lives around.

But Laruelle’s practice of medicine had taken a decidedly darker turn a few years earlier, in 2016, when he says he gave an illegal prescription to a patient for the first time. By Laruelle’s telling, the patient was a woman in her thirties who was deeply depressed. As Laruelle learned later, she had been beaten and raped on several occasions. This patient, Laruelle claims, referred others, and his drug peddling subsequently spiraled. Another female patient, he stated, “was worried about becoming homeless and told me that she could pay her rent if she also sold oxy on the street.”

“I now know that I should never have done that, as I broke the law. In my manic state, I felt I was omnipotent and could do no wrong,” Laruelle said.

The veracity of this account and its sympathetic framing of Laruelle as a doctor who erred only in trying to help patients who were suffering cannot be independently verified, and the investigatory documents that ultimately led to his arrest contain no corroboration of this particular narrative. What is known, according to an affidavit from a drug enforcement agent filed in October 2021 to support Laruelle’s indictment, is that the doctor’s prescription history shows he sold medically unnecessary prescriptions for oxycodone to at least 60 patients between September 2016 and July 2021.

The affidavit also reports on an undercover operation by the DEA between August and October of 2021. During the course of this investigation, three special agents were able to purchase illegal prescriptions from Laruelle, including oxycodone and Adderall, both Schedule II controlled substances, as well as Xanax, another controlled substance. According to the affidavit, Laruelle never performed a physical or psychological examination on the undercover agents who were posing as patients. And after one agent noted that his job involved hosting parties in Puerto Rico, Laruelle asked the agent if he could supply him with “‘coke,’ ‘weed’ and ‘Molly’” for use during a trip to Puerto Rico with his girlfriend.

In the fall of 2021, Laruelle pleaded not guilty. Then, a year later, he reversed course. “The prosecution presented a lot of evidence to support their claims,” said one of his lawyers, Gregory Ryan, managing partner of the White Plains firm Tesser, Ryan and Rochman. “And clearly, his bipolar disorder impaired his judgment and caused the criminal conduct.”

At Laruelle’s sentencing hearing this past January, Ryan’s partner, Irwin Rochman, brought up Laruelle’s long bout with bipolar disorder and invoked the concept of diminished capacity to argue that Laruelle did not deserve to serve the full sentence for his offense, which typically runs about seven to nine years. (A request for a judge to consider diminished capacity is different from the more widely known insanity defense, the latter being functionally equivalent to a not-guilty plea. The former, in contrast, only seeks to lower the punishment for the crime during sentencing.)

Allen Frances, a former chair of psychiatry at Duke University and the chairman of the task force that produced the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-IV, says that courts have historically been skeptical when defense attorneys bring up a psychiatric diagnosis at sentencing. “That’s because defendants typically have a lot to gain by faking a mental illness in this context,” he said.

But Ziv Cohen, who teaches forensic psychiatry at both Columbia and at Cornell University, said that state and federal courts are beginning to take the psychiatric condition of defendants more seriously. Cohen pointed to People v. Sepe, a 2013 case in New York State in which the defendant was found guilty of killing his girlfriend with a baseball bat, but in which his conviction was reduced from murder to manslaughter in an appeal. “The court decided that this defendant, who had a long history of depression, was suffering from an extreme emotional disturbance at the time of his crime,” he said.

In his effort to reduce Laruelle’s sentence to two years, Rochman submitted to the court a detailed report by Nadkarni, which covered all of Laruelle’s manic behavior and concluded that his severe case of bipolar disorder “was the direct cause of his illegal conduct.”

At the hearing, Federal Judge Denise L. Cote acknowledged “the torment that Laruelle has suffered due to his illness” and called Dr. Nadkarni’s report “very helpful,” but she ultimately decided on a four-year sentence. In explaining her reasoning, she alluded to the seriousness of Laruelle’s crimes, noting, “as counsel and the defendant have recognized, they happened and are happening when we as a nation are suffering from an opioid epidemic.”

Laruelle hopes to get his medical license back after he leaves prison. While his lawyers plan to argue that he is not likely to re-offend as long as he continues to remain in treatment for bipolar disorder, his lawyer Greg Ryan, acknowledges that this will be “an uphill climb.”

After all, “Laruelle did use his medical license to commit a felony,” he added. “And a medical license is a privilege — not a right.”

If you or someone you know are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

UPDATE: This article has been updated to clarify that Chase Anderson was not symptom free during his undergraduate years at MIT, as he did experience severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation when he was a freshman.

Joshua C. Kendall is a Boston-based journalist and author. His reporting on psychiatry, neuroscience, and health policy has appeared in numerous publications, including BusinessWeek, The Boston Globe, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Daily Beast, Scientific American, and Wired.