In 1989, at the age of 21, Jennifer Lunden began suffering from what she calls a “mysterious fatigue” that has dogged her ever since. At first, she was told it might be mononucleosis, but she never recovered, and her symptoms, including crushing headaches and brain fog, got worse. Doctors were perplexed or dismissive.

“It was like a wicked flu that never went away,” she recalls in “American Breakdown: Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life.” “I wanted to work; my body demanded that I rest,” she writes. “When I disobeyed what my body demanded, it punished me.”

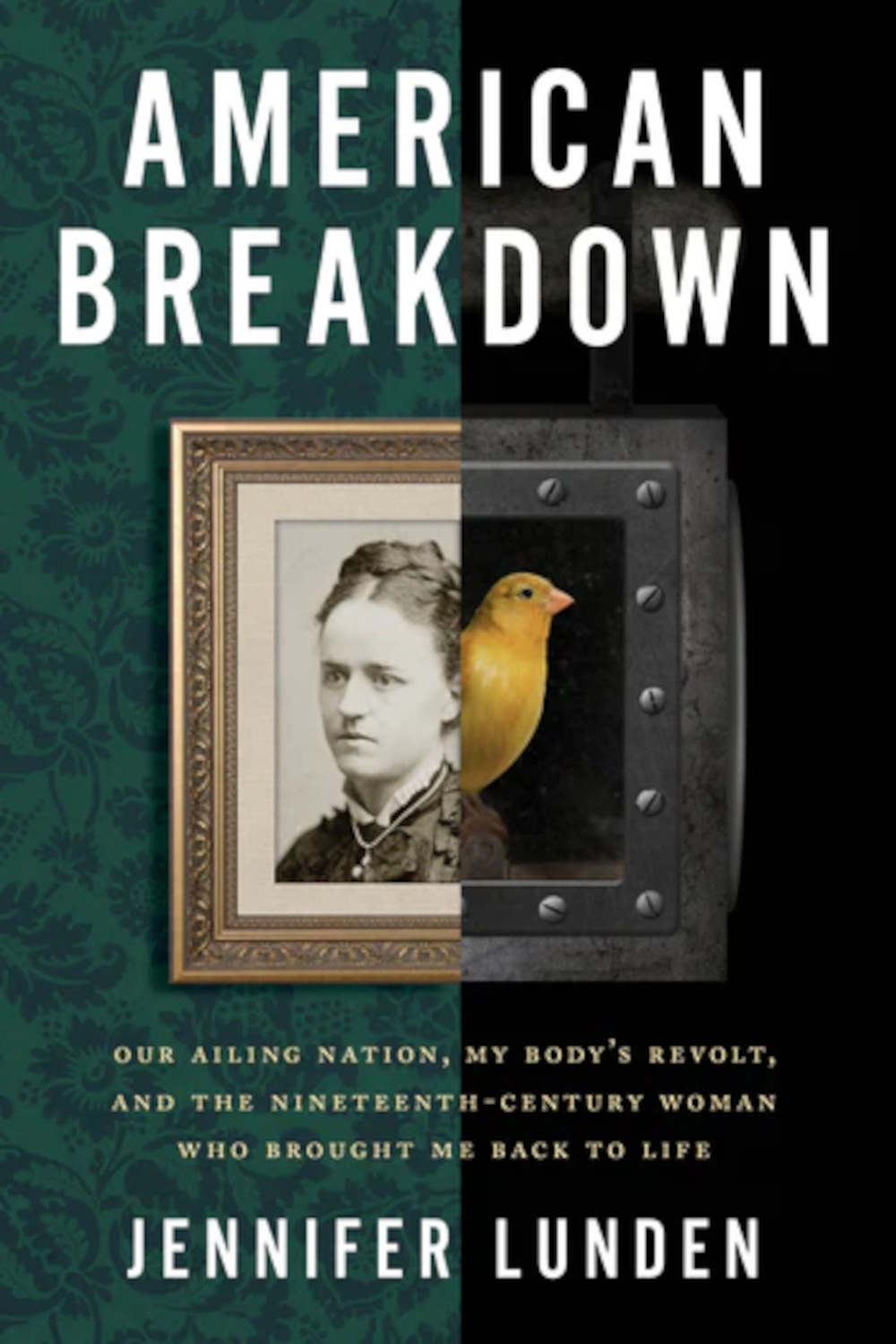

BOOK REVIEW — “American Breakdown Our Ailing Nation, My Body’s Revolt, and the Nineteenth-Century Woman Who Brought Me Back to Life,” by Jennifer Lunden (Harper Wave, 464 pages).

Five years later, while working as the caretaker of an historic house museum in Maine, Lunden ran across Jean Strouse’s acclaimed 1980 biography of Alice James, the sister of Henry and William James. Lunden would eventually come to think of James, who experienced similar debilitating symptoms, as her “bed-comrade.”

Like her “nineteenth-century doppelgänger,” who described herself as “an emotional volcano,” Lunden, at times spurred by her doctors’ statements, maintained a cordon sanitaire around her emotions. And like James, Lunden felt depressed to the point of suicidal thoughts, “It ruled my life,” Lunden writes. “It stole my body from me. It contradicted my will.”

After nine years of illness, Lunden was finally diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, also called myalgic encephalomyelitis, a baffling condition that often turns patients into unreliable narrators in the eyes of medical authorities. In fact, as Lunden notes, it wasn’t until 1988 — a year before she fell ill — that chronic fatigue syndrome was given an official name in the U.S.

Lunden interweaves her long struggle to understand her disease and find relief with passages chronicling James’s ailment, known in her day as neurasthenia. Among other things, we learn that both women’s symptoms would ebb and flow. In between bouts of debilitating illness, for example, James was fond of horse riding, tending to her greenhouse, organizing luncheon clubs, and teaching a correspondence course for women.

Lunden dives deeply into the history and latest research regarding ME/CFS, exploring possible links to synthetic chemicals and infectious diseases. Among her discoveries: More women than men are diagnosed with the condition, which, she speculates, is one reason that the “illness has been trivialized.”

In fact, a sense of medical chauvinism pervades her experience as a patient, at least early on in her illness. On one occasion, when Lunden asks a doctor if she might have chronic fatigue syndrome, the doctor replies, “If you think that way, you’ll make it so.” (And it wasn’t just male doctors: One female physician, Lunden writes, “disappeared me with her impatience.”)

Such attitudes spur Lunden to seek out alternative medicine. She recounts her experiences, and varying successes, with an assortment of treatments for chronic health conditions, including “brain-retraining” strategies like the Gupta Program and the Dynamic Neural Retraining System, which “included thanking the limbic system for its valiant protective efforts and letting it know it could now relax, visualizing happy past memories and vividly imagining the details of a healthy future.” During these exercises, she envisioned the monarch caterpillars that she raised as a child, the river where she now frequently swam as a form of therapy, and a range of tasks that her “future self” could easily perform.

All this came at a cost: Since insurance companies were reluctant to subsidize such experimental treatments, Lunden writes, she had to pay for them herself. Over the course of several chapters, Lunden details the toll such treatments take on her pocketbook and psyche. Though she eventually found part-time work as a social worker and therapist, she writes that “at fifty-four, I’ve accumulated a grand total of $1,800 in retirement savings.” At one point, she set up a GoFundMe campaign to help pay for four months of health care expenses.

“American Breakdown” fits into a burgeoning genre of detective-like accounts of coping with mysterious illness. Meghan O’Rourke’s “The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness,” for example, detailed the circuitous and costly road to being tested and then treated for Lyme disease. And in the recent memoir, “A Matter of Appearance,” Emily Wells writes about living with chronic pain and being diagnosed with Behcet’s disease, an incurable illness that causes blood-vessel inflammation throughout the body. Like Lunden, she braids her personal story with that of another 19th century woman, Louise Augustine Gleizes, who experienced what was then called hysteria. For authors like these, to become chronically ill is to become an investigator of one’s body.

But Lunden has a broader agenda. As the book gathers momentum, it turns into an indictment of the health care system and the medical establishment, especially in the second half. Lunden directs much of her ire at the Environmental Protection Agency, which she believes has fallen short in following its mandate to protect the health and safety of consumers. She notes, for example, that during the Reagan era the agency “lowered its standards for an ‘acceptable’ risk of cancer from one in a million to one in ten thousand.”

She also recounts the EPA’s recognition of “sick building syndrome” in the late 1980s, including studying the air in its own headquarters. The agency was prompted to do so after complaints from employees who had fallen sick while working in the building during renovations. The culprit, many agreed, was volatile organic compounds released from 27,000 square yards of newly-installed carpet, and one chemical was eventually pinpointed. Yet in all but one case, the EPA “denied that its employees were suffering from ‘real’ injuries,” Lunden writes, and stated that their tests showed no air quality issues, resulting in “the social gaslighting of ill people by the very government agency that was supposed to protect them — and us.”

Lunden’s attempt to balance the twinned histories of her and James’s illnesses with a takedown of the health care system is slightly unwieldy at times, but it’s nonetheless a passionate call for meaningful reform to help others like her coping with unexplained illnesses.

As she was finishing the book, during the Covid-19 pandemic, Lunden relapsed — “for me there is an unfortunate undertow toward illness” — and at one point took refuge in a rented hyperbaric oxygen chamber, which served as a kind of psychic bomb shelter. But even as complete health and wellness elude her, Lunden has managed to find hope in the promise of new medical research into ME/CFS, and in the act of self-discovery in the writing of her book and finding a kindred spirit in James.

“I’m a work in progress,” she concludes. “So are you; so are we all. And I, for one, will keep trying.”

Rhoda Feng is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C. whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Times Literary Supplement, The New Republic, The Nation, and Vogue, among other outlets.