Recently, while I was conducting a survey investigating the Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on children’s mental health, I noticed all my phone conversations were starting the same way: I would introduce myself as Tom, a medical student at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan, then ask if the person I was speaking to was the parent or guardian of the patient I was inquiring about — let’s call her Jane.

The answer was nearly always yes — electronic medical record systems are, after all, very good at tracking addresses, phone numbers, and other data needed for billing. But every so often, I got a response like this: Hi Tom, Jane is no longer living with us; I don’t know where she is now.

Whenever a patient had seemingly vanished this way, a quick look into their chart usually confirmed that they were, or had been, in the foster care system.

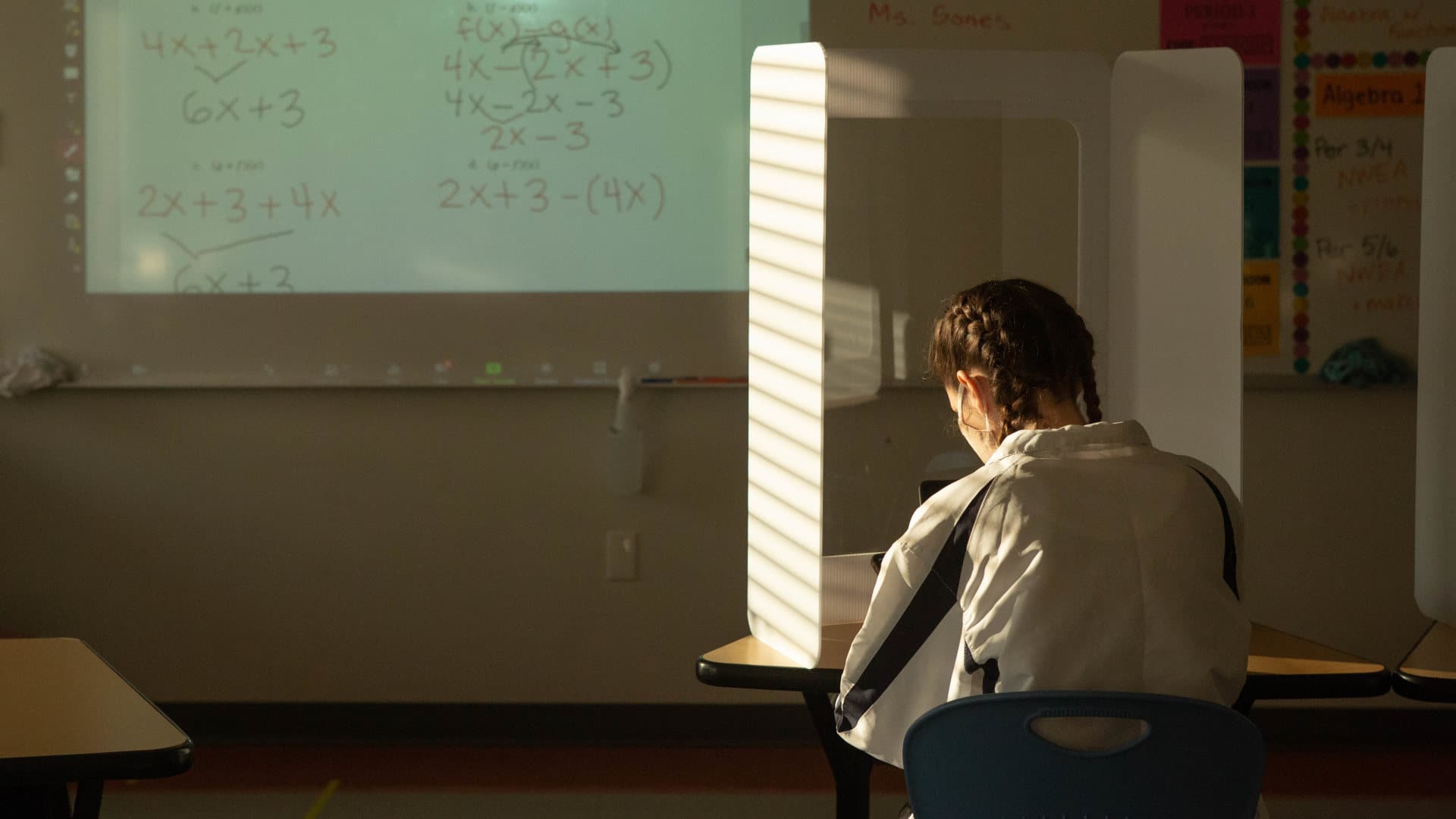

In my study, my colleagues and I were trying to untangle the thorny question of how interruptions in in-person schooling during the pandemic correlated with the rising prevalence of mental health emergencies among children and adolescents. Though hard evidence is difficult to come by, there are numerous reasons to suspect that aspects of remote learning — including a lack of in-person interaction and increased exposure to domestic violence and parental substance abuse in the home — played into the explosion in demand for children’s mental health services that began in 2020 and continues to this day.

There are also reasons to believe that these impacts may have disproportionately affected foster children, who already face tremendous instability in their day-to-day lives and relationships. Foster children are far more likely to be victims of abuse and to require individualized education plans and mental health care — services that schools, health care organizations, and governmental agencies often struggled to provide during the pandemic. Meanwhile, foster children, many of whom lacked access to primary care even before the pandemic, have been undertargeted by Covid-19 education and vaccination campaigns, potentially leading to high rates of vaccine hesitancy and greater risk of infection.

Yet researchers still don’t know the full extent of the pandemic’s toll on foster children, and we may never know. That’s because foster children do not fit neatly into our existing models of clinical care and research, and the medical field has done little to include them.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

A quick survey of recent medical research reveals that the body of literature on foster children is sparse. By the summer of 2022, thousands of papers had been published detailing Covid-19’s disparate impacts on varying demographic groups in the U.S. When I looked specifically for research focused on children in foster care, however, I could find vanishingly few studies.

Even prior to the pandemic, the medical field knew little about how inclusion in the foster system affected most health outcomes — even conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and reactive attachment disorder that are strongly associated with family upheavals during childhood. As most medical science has surged ahead, fueled by tens of billions of dollars in public and private spending, foster children have largely been left behind.

It is not hard to understand why this is the case. Data reporting systems for children in foster care vary enormously from state to state and typically place minimal emphasis on health outcomes. When health information is reported, it is often vague or incomplete. For example, the federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System — a platform designed to inform policy development and program management at federal, state, and tribal levels — reduces a vast spectrum of medical conditions to the clinically meaningless and insulting term “mental retardation.”

Researchers who do attempt to study foster children must navigate a labyrinthine review process, usually involving a state social services agency and a circuit court judge, in addition to a traditional Institutional Review Board. Though well-intentioned, these measures go far beyond the regulatory requirements for most research into other medically vulnerable populations, and they can make it virtually impossible for studies targeting foster children to gain approval.

Unfortunately, my current study on remote schooling will do nothing to mitigate these problems. When my coauthors and I eventually publish our results, the quarter of a million children who enter foster care in the U.S. each year will most likely be relegated to a brief note acknowledging their absence as a limitation of our work. There is little that my research group can do about an electronic medical record system that loses track of foster children, and there is even less we can do about a medical research establishment that still, by and large, treats some of the most vulnerable members of society as statistical inconveniences.

What I can and will do is work to ensure that the mistakes of exclusion are not repeated. Though the medical establishment has made some progress combating the homogeneity of both its researchers and its research subjects, these efforts continue to overlook many marginalized populations, such as children in foster care. In an evidence-based paradigm of clinical medicine, ignoring these patients in research studies is akin to turning them away at the doors of the hospital.

Not every research study will be a perfect model of inclusivity, but it is vital that we in the medical field acknowledge and learn from our failures. Although I don’t know what my next study will be, I know that, as I design it, I will spend more time thinking about whom I might be inadvertently excluding, and how I can bring them into the fold.

Thomas Leith, MD, is a recent graduate of the University of Michigan Medical School. He will begin residency in emergency medicine at the University of Massachusetts this summer.