EPA Proposes New Emissions Rules at Chemical and Plastics Plants

The administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency used the smokestacks of Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” as the backdrop on Thursday to announce new rules aimed at reducing harmful, toxic emissions from chemical and plastics plants across the country.

“For generations, our most vulnerable communities have unjustly borne the burden of breathing unsafe, polluted air,” Michael S. Regan, the nation’s top environmental regulator, said from behind a podium bearing the EPA seal, with grazing cows and one of the region’s ubiquitous chemical plants in the distance behind him.

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

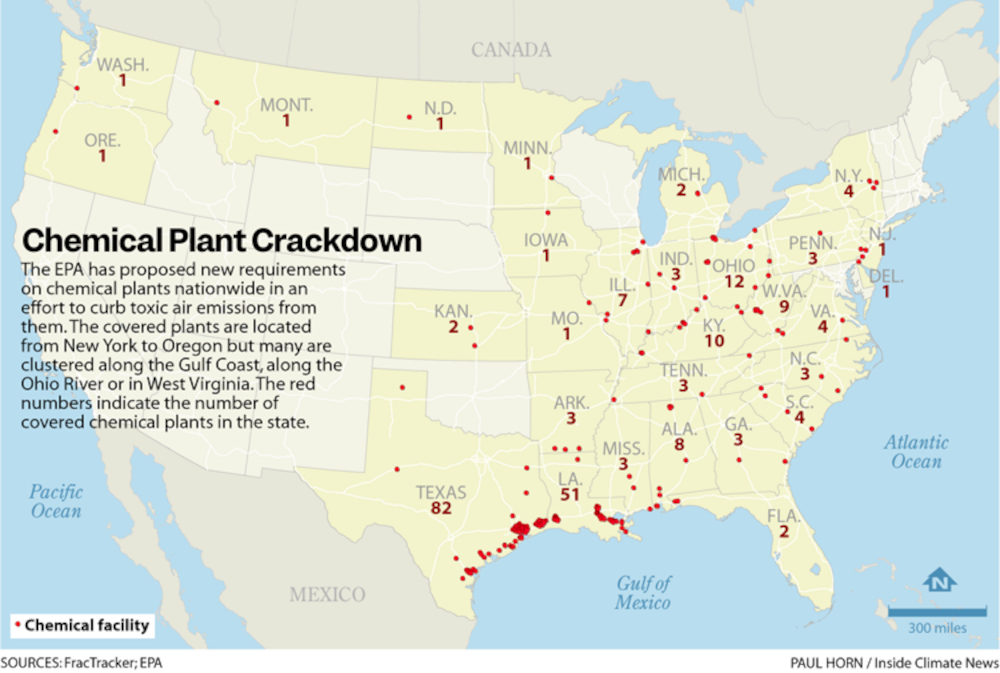

Manufacturing facilities potentially subject to the new emissions controls, from New York to Oregon, are concentrated along the Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas, with clusters in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia. They often emit chemical byproducts that have been linked to cancer and other health risks and disproportionately impact communities of color and low-income white neighborhoods.

These plants are already subject to what the EPA considers to be “maximum achievable control standards” to limit pollution. But Thursday’s proposed rules will require additional pollution control measures to counter continuing health risks those communities still face despite existing pollution controls. The new rules also reflect more current research findings on health risks from some chemicals, like the carcinogen ethylene oxide.

It has been nearly two decades since the rules were last updated, so action was long overdue, environmental advocates said.

“Today’s announcement is undoubtedly a game changer, especially for children,” Regan said, noting that youth are most vulnerable to toxic pollution. “There is no higher priority for me than protecting the children of this country.”

He made the announcement in St. John the Baptist Parish, where Denka Performance Elastomers has become a lightning rod for controversy related to emissions of the toxic chemical chloroprene near an elementary school.

The American Chemistry Council, the leading lobby group for the chemical industry, issued a statement saying that its member companies “are committed to being good neighbors and helping safeguard communities and the environment.”

Since the 1980s, the group said, “total toxic releases” and other air emissions “in the U.S. have fallen sharply,” even as population and gross economic output have grown.

Still, the council said, “we are concerned that EPA may be rushing its work on significant rulemaking packages that reach across multiple source categories and could set important precedents. We will be engaging closely throughout the comment and review process.”

Litigation by Earthjustice compelled EPA to meet a deadline of March 31 to decide whether to update the rules governing what Congress defines as “hazardous air pollutants.” The nonprofit environmental law group had represented several environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, Louisiana Environmental Action Network, Concerned Citizens of St. John, and California Communities Against Toxics.

Taken together, the proposed rules mark a critical step “in protecting communities from our nation’s largest and most hazardous chemical plants,” said Adam Kron, an Earthjustice attorney.

Regan recalled his visit to what many call Cancer Alley in 2021, which EPA dubbed “Journey to Justice.”

“I distinctly remember standing on the grounds of a school that was a stone’s throw away from a facility that manufactures toxic chemicals. The children who attend that school, who study at that school, who eat lunch at that school every single day, look just like my son Matthew,” said Regan, who is Black. “I met with families all across this community. And nearly every person that I spoke with knew someone who suffered from an illness that they believed was connected to the pollution in the air they breathe.”

Robert Taylor, president of Concerned Citizens of St. John Parish, an environmental justice group, thanked Regan for coming in 2021, and then following through with action. “The man actually walked the streets, knocked on doors and he got to meet people,” he said. “And he is living up to that commitment by what we are seeing today.”

Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice in New Orleans, called Thursday “a truly historic day” in the 30 years she has been working in the area known as Cancer Alley, a 130-mile stretch along the Mississippi River that is dotted with more than 200 industrial facilities, including oil refineries, plastics plants, chemical plants, and other factories that emit significant amounts of harmful air pollution.

Data collected by the Environmental Defense Fund shows that 83 percent of these facilities have been out of compliance under the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, or the nation’s law requiring proper management of hazardous and non-hazardous solid waste.

Regan said the rule would cut the emissions of dozens of toxic air toxic pollutants and focuses new attention on several highly toxic chemicals, most known to cause cancer in humans:

- ethylene oxide, a flammable gas used in manufacturing other chemicals that go into making a range of products, including antifreeze, textiles, plastics, detergents, and adhesives.

- chloroprene, a liquid used in the production of neoprene at the Denka plant in La Place, Louisiana. Neoprene is found in wetsuits, gaskets, hoses, and adhesives. EPA considers it likely to cause cancer in people.

- 1,3 butadiene, a highly flammable gas primarily used to make plastic and rubber products.

- benzene, a highly flammable liquid used to make other chemicals that go into plastics, resins, nylon, adhesives, sealants, and synthetic fibers. It’s also used to make some types of rubbers, lubricants, dyes, detergents, drugs, and pesticides.

- ethylene dichloride, a highly flammable liquid used to make plastic, polyvinyl chloride, resin, other chemicals, and in the manufacturing of petroleum and coal products.

- vinyl chloride, a colorless gas usually handled as a liquid under pressure, used to make polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastic and vinyl products.

Some of these chemicals, like ethylene oxide and chloroprene, are emitted from a relatively small number of facilities. Others are more widely used.

The EPA inspector general’s office last year found that the EPA needed to act on chloroprene and ethylene oxide, saying EPA’s modeling and monitoring indicated that as many as a half-million people in some areas of the country may be exposed to unacceptable health risks from them.

In making its announcement, EPA said its proposal would update several regulations that apply to chemical plants. The proposed rules would reduce 6,053 tons of air toxics emissions each year, which are known or suspected to cause cancer and other serious health effects.

Facilities that make, store, use, or emit ethylene oxide, chloroprene, benzene, 1,3-butadiene, ethylene dichloride, or vinyl chloride would be required under the new rules to monitor levels of these air pollutants entering the air at the fenceline of the facility — something that environmental justice advocates across the country have been advocating for years. EPA would also make the monitoring data public.

Fenceline monitoring amounts to more than tracking emission levels at a chemical plant’s property line, said Jane Williams, executive director of California Communities Against Toxics, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit that prompted the EPA to act.

“They have to manage their plant to the metric,” she said. “It’s not just monitoring.”

She described fenceline monitoring as “the police body cams of the chemical industry.”

The rules also seek to address another frequent complaint from people who live near chemical plants — that the EPA has been too lax regarding emissions released during start-ups, shutdowns, emergencies, or malfunctions.

Federal courts have told the EPA since 2008 that chemical plants cannot use events like malfunctions or shutdowns as broad exemptions to clean-air regulations, said Kron, the Earthjustice attorney.

Along the Gulf Coast, environmental advocates have complained about emissions related to disturbances from major storms, such as hurricanes, and malfunctions that cause plants to relieve pressure by burning off or “flaring” chemicals in pipes or tanks, often sending flames or smoke billowing into the air.

These can cause “huge toxic releases, and the way the rules are written, that is completely permissible,” Kron said. “That needs to change.”

Regan seemed to agree.

“Communities don’t stop breathing during a hurricane,” he said. “They don’t stop breathing during an event. It is the company’s responsibility to control their pollution.”

Environmentalists expect robust industry pushback during the rule-making process, which will include a 60-day comment period and at least one virtual public hearing.

“I expect the industry to buck and scream and go to Congress,” said Williams, the California activist. “We look forward to working with the administration to ensure the final rules remain as strong as the rules proposed today.”

James Bruggers is reporter covering the U.S. Southeast for Inside Climate News’ National Environment Reporting Network.