Astrophysicist Joseph Silk’s “Back to the Moon: The Next Giant Leap for Humankind” is contemporary, futuristic, and nostalgic all at the same time. Contemporary because roughly half of the book is essentially a précis of the current state of cosmology and astrophysics; futuristic because much of it is in future tense, grammatically and thematically; nostalgic because it also reads very much like the classic aspirational works about space exploration by authors such as Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Willy Ley, and others way back in the days of V-2 rockets and Disney space documentaries.

BOOK REVIEW — “Back to the Moon: The Next Giant Leap for Humankind,” by Joseph Silk (Princeton University Press, 304 pages).

The book begins as something of a polemic, a clarion call for humanity to return to the moon for good, similar to Robert Zubrin’s 1996 book “The Case for Mars: The Plan to Settle the Red Planet and Why We Must.” But whereas Zubrin, writing with an engineer’s sense of nuts-and-bolts practicality, was big on the hows and perhaps somewhat fuzzier on the whys, Silk’s approach is roughly the opposite.

He briefly lays out the legacy of past lunar exploration, including the Apollo program and the familiar justifications for space exploration and development: finding new economic resources and raw materials; establishing human colonies and a self-sustaining infrastructure as a new arena of international cooperation; and a way to hedge our bets against human-made, environmental, or cosmic disaster with a permanent off-Earth presence. But it’s clear that for Silk, all of that is incidental to what he sees as the main driving force to return to the moon, as he enthuses in the book’s preface: “Let’s do science!”

That’s exactly what the next four chapters or so do, as Silk, a professor at Johns Hopkins University and author of many previous books on cosmology and astrophysics, provides an excellent introduction to the basics of cosmology, from the beginnings of the universe to its possible ultimate end, touring important points along the way, including black holes, stellar evolution, supernovas, radio astronomy, dark matter, exoplanets, even the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI. Silk’s expertise in and enthusiasm for his subject matter are readily apparent — perhaps overly so, because the lengthy digression is liable to leave the average reader thinking, “Well, this is all very interesting, but what exactly does it have to do with going back to the moon?”

The answer, as Silk explains in ambitious detail, is that the moon is an ideal platform to “do science.” He notes that for most of its history thus far, cosmology has actually been a rather inexact discipline. “When I began to work in the field of cosmology about a half-century ago, we were discussing precisions at best of 50 percent for any measurable parameter,” he writes. With such relatively crude data, “We were living in the dark, cosmologically speaking.” That changed markedly with the development of telescope-bearing satellites and deep space probes that could collect data outside of the Earth’s obscuring atmosphere — compare the images from the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes with the best ground-based images, for example.

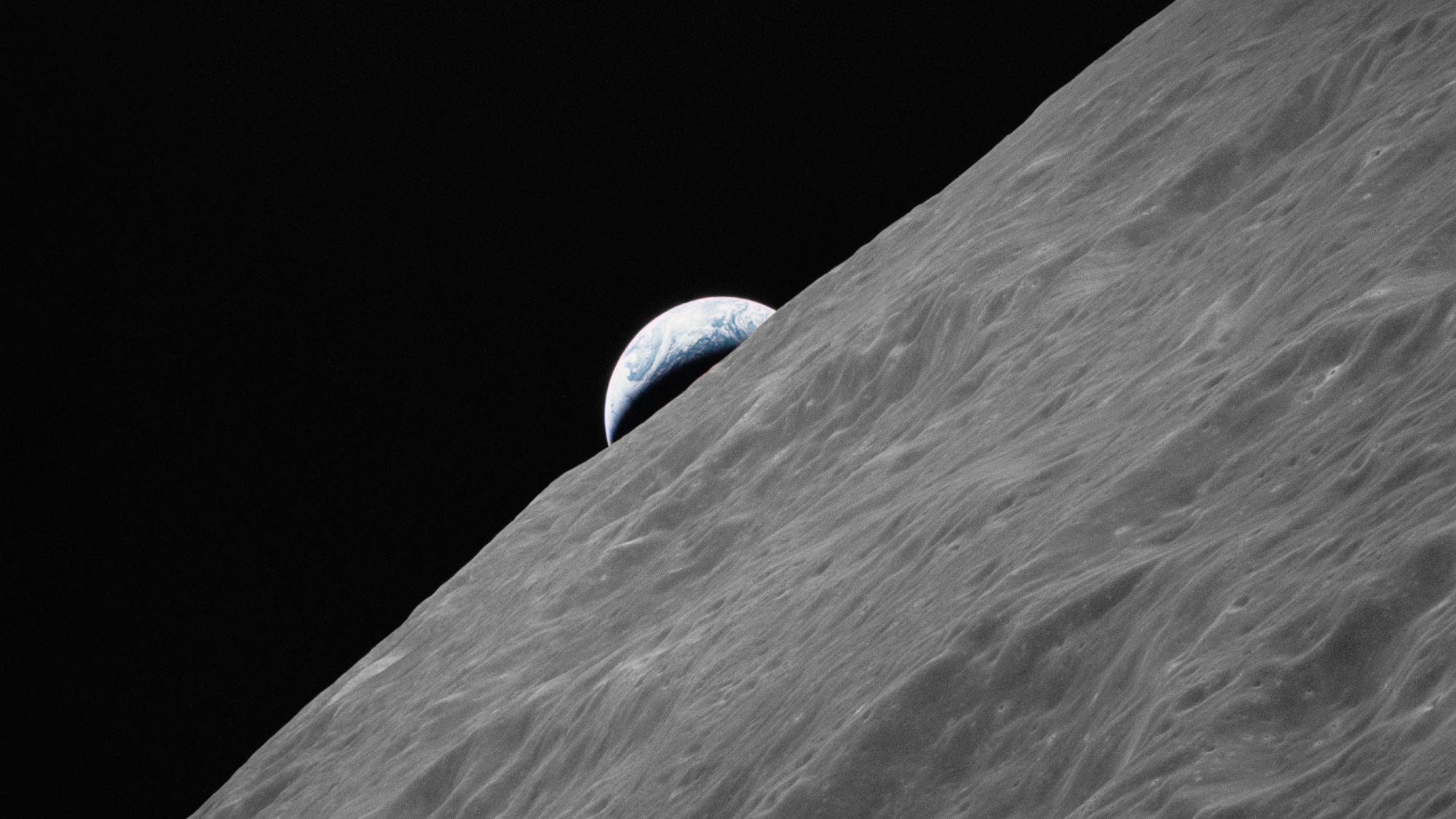

Lunar observatories are the next step beyond those resources, particularly huge crater-based infrared and radio instruments, able to make the sort of astrophysical and cosmological measurements that require the profound silence, cold, and darkness of the lunar far side away from the electromagnetically busy and noisy Earth. “We will do cosmology on the moon,” Silk writes, “and study the structure of distant clouds with unprecedented accuracy that will allow us to unlock the secrets of the beginning.”

Unfortunately, “Back to the Moon” seems to largely preach to the converted. “We can unlock the secrets of the universe thanks to the telescopes that we will construct on the moon,” says Silk. But those who are already passionate about astrophysics, cosmology, finding extraterrestrial life, and unlocking the secrets of the universe don’t need to be convinced of the value of giant lunar observatories, and aren’t worrying much about exactly how such facilities are to be built, maintained, and paid for. The people who have to be persuaded are those footing the bill, whether average taxpayers or self-made billionaires, who are probably going to be somewhat less concerned with helping cosmologists move around some decimal places. Perhaps the book might have been more aptly titled “The Next Giant Leap for Cosmology” rather than “humankind.”

“Back to the Moon” finally does go back to the moon in its closing chapters, resuming the sort of Clarkean speculations and extrapolations touched on in the beginning of the book. Silk briefly describes a probably too utopian 22nd-century lunar scenario, with thriving cities, industry, resorts, and scientific facilities, but also touches upon the darker possibilities of international competition over territory and resources leading to conflict and even open warfare.

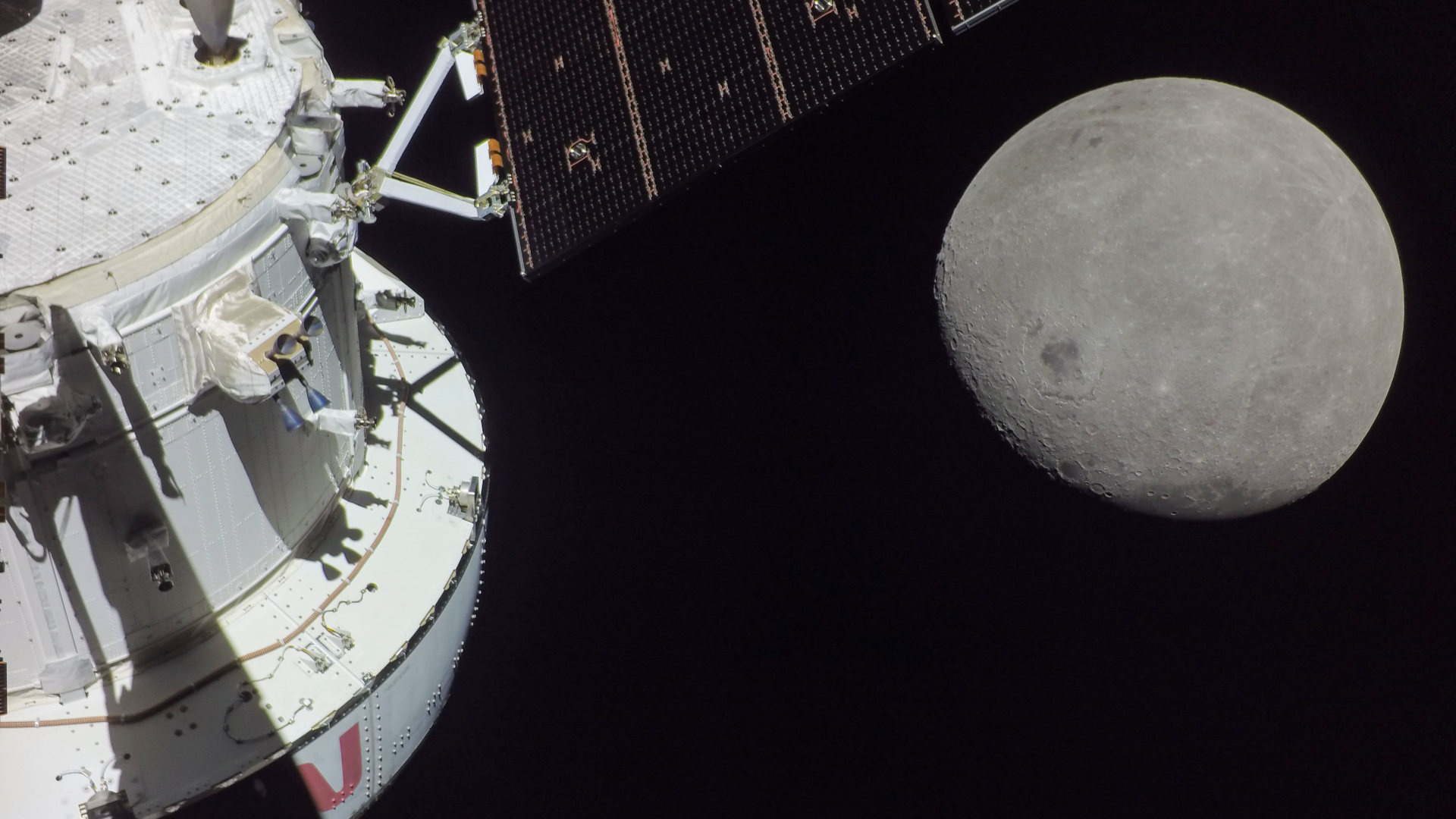

Those looking for more immediate justifications and motivations for current and near-future lunar possibilities such as NASA’s Artemis project — which seeks to return humans to the moon by 2025 and just completed a successful uncrewed voyage — are likely to be disappointed by this account. The book is to a large extent a blue-sky (so to speak) wish list for the cosmological community, certainly a valid and important set of aspirations but not one likely to seduce the shorter-term and goal-directed orientation of politicians, billionaires, and much of the public.

Even Silk notes that “development and colonization of the moon requires a long journey that will take perhaps half a century to develop, and centuries to complete.” Just as science was never the true impetus of the Apollo program, nor enough to sustain it once its original goal had been achieved, probing the secrets of the universe is unlikely to be enough on its own to support the establishment of a permanent human presence on the moon.

But grandiose as they may sometimes be, and despite their occasional disregard of the practical, the realistic, and the inevitable limits we can’t escape, we still need the sort of dreams so enthusiastically presented in “Back to the Moon.” Perhaps even more so now, as we celebrate the 50th anniversary this month of the most recent human journey to the moon. To paraphrase Clarke, they inspire us to push beyond the limits of the possible into the impossible.

Though the magnificent visions of the Asimovs and Bradburys and Clarkes never quite came true, humans have reached the moon and established a continuing presence in space, even if it’s considerably less aesthetically elegant than Pan-Am space clippers and wheeled space stations and domed cities on the moon and Mars. The visions of “Back to the Moon” may ultimately be impractical or even impossible, but they provide the motivation for somewhat more feasible dreams.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It is saddening to envision the dark reality that humanity will no longer exist on this planet due to human activity over-heating the planet. Is it elitist arrogance to pursue scientific endeavors that do nothing to promote human survival on its home planet. More is known about the surface of the moon than the surface of Earth’s oceans, where it is known that life forms do exist but remain unexplored. It must be arrogance to believe it is possible for humans to engineer a planet for human occupation and yet remain ignorant about how humans have engineered the destruction of own species on the only inhabitable planet in this solar system.