According to Cambodian lore, the ocean was once ruled by the king of the Naga empire. The Naga were an amphibious people who made their home between land and water. A prince discovered this underworld when he traveled to an island and met its princess on the shore. Naturally, they fell in love. After the prince proved his mettle, the king blessed their marriage by swallowing the ocean, revealing the land below. “The land born of water was Cambodia,” writes journalist Abby Seiff in her new book, “Troubling the Water: A Dying Lake and a Vanishing World in Cambodia.”

Cambodia’s deep connection to water — culturally, ecologically, economically — is at the heart of Seiff’s book. It’s an elegy to Tonle Sap Lake, Southeast Asia’s largest body of freshwater and one of the world’s richest inland fisheries. Fed by a branch of the Mekong River, the lake is more of an inland sea, one that shrinks and swells, up to six times its size, with the dry and rainy seasons. But dams, overfishing, and climate change threaten this ancient rhythm. Fish are vanishing from the lake. On Tonle Sap, Seiff shows, this risks an entire way of life.

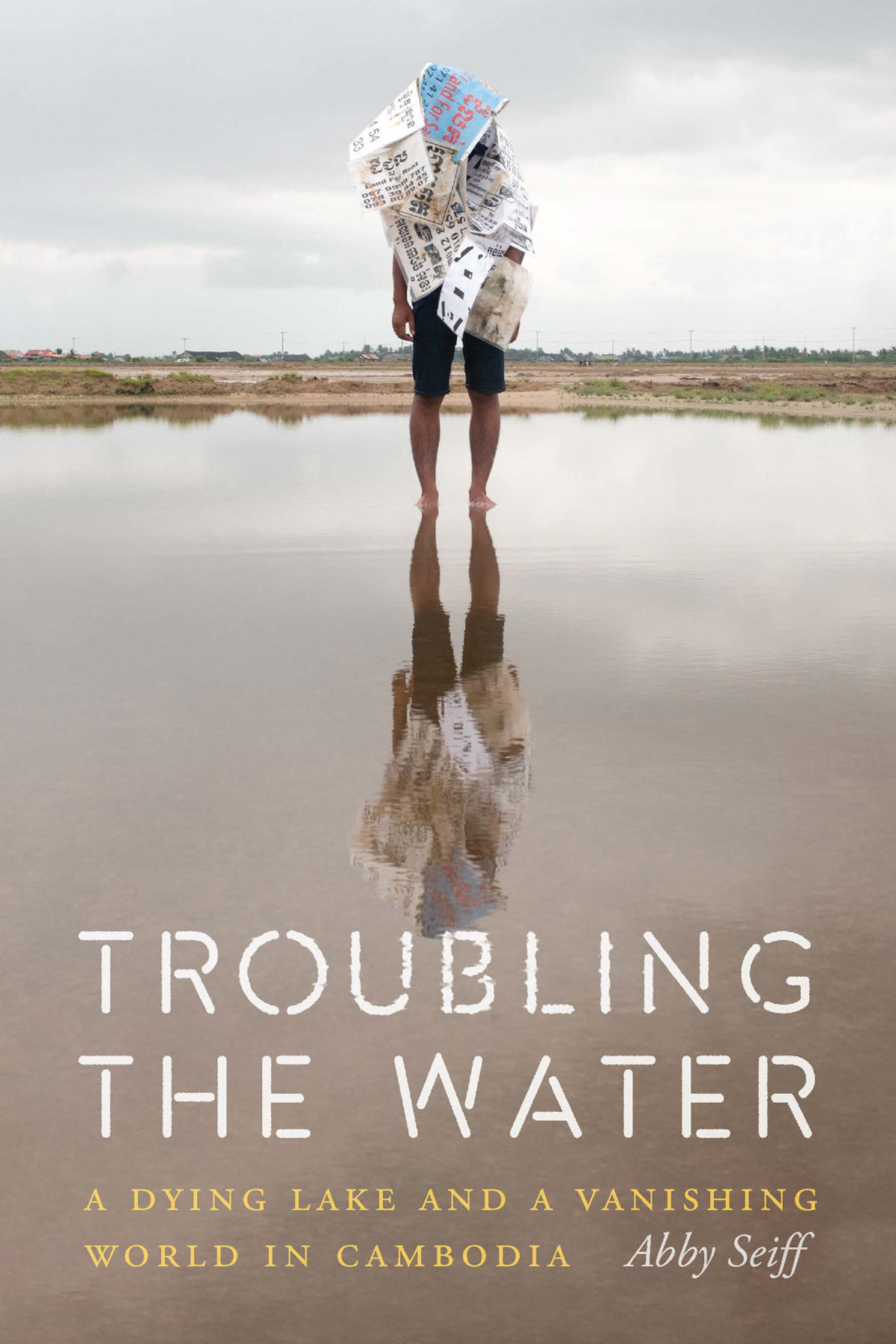

BOOK REVIEW — “Troubling the Water: A Dying Lake and a Vanishing World in Cambodia,” by Abby Seiff (Potomac Books, 162 pages).

A unique water cycle underlies the riches of Tonle Sap Lake. The lake depends on the Tonle Sap River, a tributary of the Mekong in the dry season, itself one of the most biodiverse river basins in the world, second only to the Amazon. Twice a year, the Tonle Sap River reverses itself. It’s the only river in the world to do so, Seiff writes. It starts in May, when the rainy season kicks off. Monsoons flood the Mekong, sending a wall of water — and with it, silt and nutrients — down the Tonle Sap and into the lake. The lake swallows the land, leaving only treetops to gesture to the plain below. Residents anchor their rafted homes to the submerged tree trunks, and entire villages take float. Then, come November, the rain tapers off and the Mekong subsides. The lake, swollen with rainwater, pours into its parent river and back into the Mekong. Floating homes settle back onto their stilts.

“Scientists call that a monotonal flood-pulsed system; poets liken it to a beating heart,” Seiff writes. The flood pulses are as essential to the region and national identity as a heartbeat is to a body. Once, they fed the ancient city of Angkor, whose ruins sit on the north side of the lake. Today, rice paddies dot the floodplains and fish is the main protein for an estimated 80 percent of the country. Fishers draw in heaps of riel, the small, oily, silvery fish that bears the same name as the national currency. They’re processed into the fermented paste prahok, a mainstay of Cambodian cooking.

But the heartbeat is weakening. Climate change has strengthened the droughts that grip the region. Without rainfall, there’s nothing to power the pulse. For the past decade, the Mekong’s water levels, and in turn, Tonle Sap’s, have steadily declined. In the searing heat, many villagers are facing wildfires for the first time in their lives.

On top of that, dams are on the rise as countries in the Mekong region strive to meet power needs and support development. But dams obstruct fish migration and starve the drought-stricken river basin of water and nutrients. In China, dams on the Lancang River, as the upper half of the Mekong is known, retain trillions of gallons of water — effectively withholding supply from southern neighbors. Still, the lower Mekong nations — Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam — maintain more than 100 dams of their own, and so their consequences cascade downstream.

The problems of dams and climate change are compounded by overfishing. In the last decade, the government has established conservation zones, but they are poorly enforced, and the fishery patrol is easily paid off. Illegal fishing is rampant, and forces individuals to engage in illegal practices themselves, at a much smaller scale. Seiff speaks with a couple in their 70s struggling to catch enough to feed themselves. Patrol officers confiscated their traps, which are considered illegal because they’re either made with wood from protected forests or use nets with holes smaller than permitted. For the couple, who spent their entire lives subsisting off the lake, these methods are a matter of survival.

Seiff’s reporting is intimate, taking readers into the homes of fishers on the margins. She describes villages of homes that float on rafts of bamboo or steel oil drums, and houses with tarp for walls. For a picture of Tonle Sap’s former glory, Seiff looks to the archives. Explorers and military officials are “breathless” in their accounts of the lake, she notes. In the 13th century, a Chinese emissary was awed by the biodiversity. “There are giant soft-shell turtles and alligators as big as large pillars,” he wrote. In 1871, one French naval officer marveled at its abundance: “The shivering on the surface indicates the presences of the fish.” Seiff also pulls from Cambodian mythology, the weight of which sometimes trickles into her own occasionally twee prose.

Most remarkable is the speed with which the Tonle Sap system has unraveled. Seiff encounters many who needn’t reach far to recall better times on the lake. Some remember the now-critically endangered Mekong giant catfish; others, fish so plentiful they’d flop right into your boat. The book opens in 2016, in the middle of one of the worst droughts ever recorded in Southeast Asia. By 2019, the river’s reversal lasted just six weeks — a fraction of the usual five months. Then, in 2020, “the river never quite reverses course,” Seiff writes. “For nearly the whole wet season, the height of the Tonle Sap stays too low to push any significant amount of water upstream.”

“Troubling the Water” is a time capsule: contained, viewed from a distance. Seiff spent nearly a decade in Southeast Asia, freelancing and working at The Cambodia Daily and The Phnom Penh Post. In a note on translations, she thanks her interpreters for “put[ting] up with my barang fumbling,” slang for Westerner. There is also a physical separation. Seiff finishes writing her book from New York City. There, she remembers the lake through a colleague’s photographs, traces the river on a yellowed map, and scopes out floating villages in satellite imagery.

Her close focus on the lives of ordinary people doesn’t offer much to the reader who is curious about what the Cambodian government will make of this crisis. Then again, Seiff doesn’t seem hopeful much can be done: “If it is too late to turn back the clock and restore the Tonle Sap, as I fear it may be, let this be some small attempt to memorialize a place and time before it vanishes.”

Lina Tran is science writer from the Alabama coast who is based in Milwaukee.