Millions Spent by Government on a Heart Pump Known to Be Faulty

In 2014, when the Food and Drug Administration found serious problems with a life-sustaining heart pump, its warning letter to the manufacturer threatened to notify other federal health agencies about the inspection’s findings.

But for years, no such alert ever went out. Instead, the agency added the warning letter to an online database alongside thousands of others, following its typical procedures, an FDA spokesperson said.

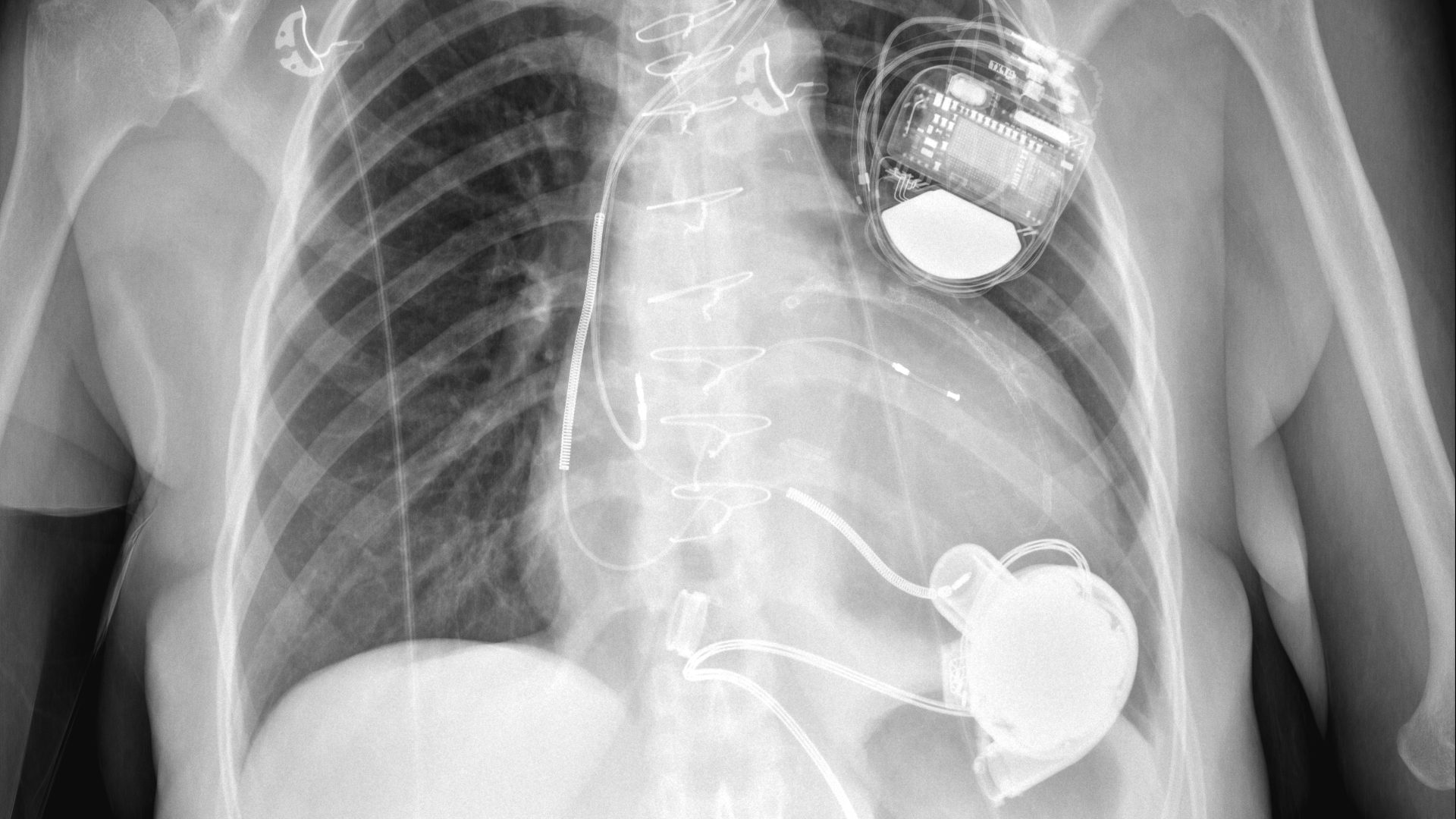

Agencies such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs went on paying to implant the HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device, or HVAD, in new patients even though federal inspectors had found problems with the device linked to patient deaths and injuries.

Taxpayer dollars continued to flow to the original device maker, HeartWare, and then to the company that acquired it in 2016, Medtronic, for seven years while the issues raised in the warning letter remained unresolved.

This story was originally published by ProPublica and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

If crucial safety information in FDA warning letters doesn’t make it to other arms of the government responsible for deciding which medical devices to pay for, experts said patients are the ones put at risk.

“It’s clearly a breakdown of communication,” said Rita Redberg, a cardiologist at the University of California San Francisco who researches medical device safety and regulation. “It’s not just the money, obviously. It’s people’s lives.”

The FDA acknowledged that it doesn’t directly notify other agencies when it issues warning letters, pointing instead to its online database, which is accessible to both government officials and the public. “The FDA’s decisions are intended to be patient-centric with the health and safety of device users as our highest priority,” the agency spokesperson said in an email.

The HeartWare letter was removed from the public database about two years ago, even though the problems remained unresolved and patients were still receiving implants. The database clears out letters that are more than five years old.

CMS, which oversees the Medicare and Medicaid programs, would not say why it continued paying for a device that didn’t meet government standards. It directed questions about the HeartWare warning letter to the FDA. “CMS does not have oversight of the manufacturing and related safety assessments of a medical device manufacturer,” a spokesperson said in an email.

The spokesperson noted that CMS requires heart pump patients to have specialized medical teams managing their care, which should monitor FDA communications regarding safety of devices.

CMS doesn’t track data on devices by manufacturer, so it’s essentially impossible to calculate its total spending on HVADs. One 2018 medical journal study found that Medicare and Medicaid paid for more than half the cost of all heart pump implants from 2009 to 2014. If that rate of spending continued, CMS may have spent more than $400 million on implanting HVADs since 2014.

A spokesperson for the VA said his agency was never notified about the HeartWare warning letter. The VA paid HeartWare and Medtronic more than $3 million after the FDA issued the letter in 2014. It offered this explanation for why: “It’s important to note that FDA Warning Letters are notifications issued to manufacturers found to be in significant violation of federal regulations. They are not product recalls.”

In the case of the HVAD, the FDA’s failure to make sure its warning reached beyond the manufacturer may have had life-and-death consequences.

In August, ProPublica reported that federal inspectors continued finding problems at the HVAD’s manufacturing plant for years. Meanwhile, the FDA received thousands of reports of suspicious deaths and injuries and more than a dozen high-risk safety alerts from the manufacturer.

The documents detailed one horrifying device failure after another. A father of four died after his device suddenly failed and his teenage daughter couldn’t resuscitate him. Another patient’s heart tissue was charred after a pump short-circuited and overheated. A teenager died after vomiting blood as his mother struggled to restart a defective pump.

In June, Medtronic ended sales and implants of the device, citing new data that showed patients with HVADs had a higher rate of deaths and strokes than those with a competing heart pump.

Medtronic declined to comment for this story. It has previously said it believed that after the 2014 warning letter the benefits of the HVAD still outweighed the risks for patients with severe heart failure.

Experts said the lack of communication between federal agencies when serious device problems are found is baffling but not surprising. It fits a broader trend of device regulators focusing more on evaluating new products than monitoring the ones already on the market.

“The priority is to get more medical devices out there, paid for and getting used,” said Joseph Ross, a professor of medicine and public health at Yale University who studies medical device regulation.

Other U.S. health care regulators move more forcefully when providers and suppliers don’t meet the government’s minimum safety requirements for an extended period, putting patients at risk.

Take hospitals. When inspectors find a facility is not meeting safety standards, CMS can issue an immediate jeopardy citation and, if problems aren’t fixed, move to withhold federal payments, which make up substantial portions of most hospitals’ revenues. In the rare cases when hospitals don’t take sufficient action, CMS follows through and revokes funding.

Redberg, the UCSF cardiologist, said the lack of similar action for medical devices offers a clear “opportunity for improvement.” At minimum, the FDA could establish processes to directly inform other agencies when it issues warning letters and finds serious problems with devices being sold in the United States.

“If the agency’s mission is to protect public health, they would want to do these things and move quickly,” she said.

Neil Bedi reports on the federal government for ProPublica in Washington, D.C.