In late winter 2020, when the full gravity of Covid-19 was only starting to come to light in New York City, journalist Dan Koeppel sent a text to his cousin, Robert Meyer, an emergency room doctor at the Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx.

“How are you doing? I’m worried for you.”

“Hanging by a thread,” Rob replied.

“Are you seeing a lot of cases?”

“Yes.”

“On a scale of 1 to 10, where do you think you are?”

The answer arrived 10 minutes later: “100.” After that, Koeppel encouraged Meyer to text, email, and call him about what was going on, as a coping mechanism. It eventually became a diary of sorts, and that, combined with interviews with Meyer’s colleagues, became “Every Minute Is a Day: A Doctor, an Emergency Room, and a City Under Siege.”

BOOK REVIEW — “Every Minute Is a Day: A Doctor, an Emergency Room, and a City Under Siege,” by Robert Meyer, M.D., and Dan Koeppel (Crown, 256 pages).

Montefiore is affiliated with the neighboring Albert Einstein College of Medicine and is home to the second-largest medical residency program in the United States, after the Mayo Clinic. It is part of a sprawling system with many buildings, labs, classrooms, and even housing for residents. Montefiore is the largest employer in the Bronx, “one of the poorest, least healthy urban counties in the U.S.,” as the book points out. The area is also filled with nursing homes. All of these factors came together during the pandemic to flood the hospital’s ER.

Meyer’s nearly 25 years at Montefiore had given him a wealth of experience, and he and his colleagues were prepared for everything. Everything except Covid-19. But in fairness, no hospital was ready.

As early as January, doctors at Montefiore had started to hear about patients with symptoms similar to the U.S.’s first confirmed patient, who had returned from Wuhan to his home in Washington state on Jan. 15 and tested positive for Covid-19 a few days later. Around the same time, Meyer reports hearing stories of New Yorkers coming to the hospital complaining of symptoms like fever, cough, and fatigue and being treated for the flu and released. One doctor told him that they had sent information about a suspected case to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but there was no response. Later on, Meyer muses: “Were they Covid? Later studies would say probably, but at the time Covid-19 wasn’t even on our radar.”

By early March, positive Covid-19 cases were detected in New York and the number of patients admitted to the hospital with Covid-19 started building slowly — and then exponentially. Because of its location near many nursing homes, the Montefiore ER saw many of the city’s sickest patients. Meyer and Koeppel are not shy about pointing out the systemic factors that made everything about the pandemic worse for this hospital. “Life in the Bronx is hard and resources are scarce,” they write. “All those comorbidities that have led to all those Covid fatalities in poor communities around the world were preventable in a way that Covid itself wasn’t.”

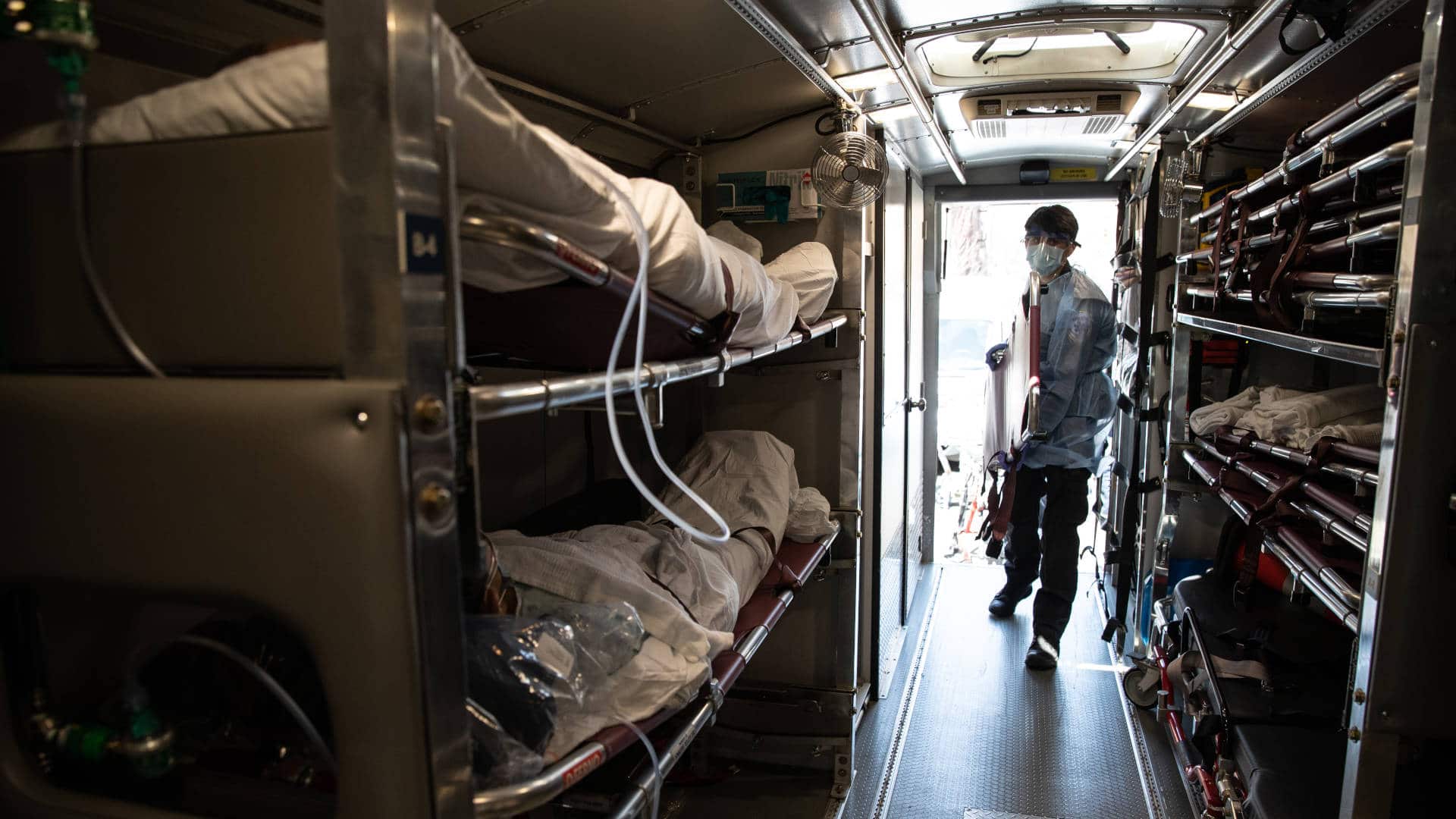

Through Meyer’s eyes, the authors paint a gruesome scene of the early days of the pandemic: ERs packed with stretchers, not enough ventilators, and soon, not enough personal protective equipment. The speed with which the virus took hold was unexpected, even for medical professionals, which led to overcrowding and the turning away of patients. By the second Saturday in March, the hospital was running out of places for those who didn’t make it through. Triage tents were set up outside. Doctors were starting to get sick; some would eventually die.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

The learning curve was steep, and as new information became available, the protocols for handling and treating patients evolved. But chaos ensued in those early weeks. For example, the ER was overwhelmed with so many people needing lung X-rays that normal safety precautions were cast aside, leaving doctors and staff routinely exposed to radiation. For the beleaguered hospital staff, there was just not enough time and too much to do.

As the pandemic continued, Meyer realized that a core element of his doctoring had changed: his relationship with his patients. No longer did he have the time to get their full story and profiles. They couldn’t even see his face. He didn’t have the time to get to know them, and they couldn’t have their families with them while they fought to survive. The struggle to retain humanity and tenderness in the face of unrelenting tragedy is returned to again and again: “When you face an emergency room where it seems like everybody is dying, where there’s no room to move, where every patient is gasping for air, you just can’t be the doctor you want to be.”

And so he finds ways to make small connections, even after death. To make it easier on a woman who has snuck past security to see her father’s body, he wraps gauze around his head to close the open mouth that occurs when rigor mortis sets in. He learns about patients after they’ve died from the relatives who call and text. But it never feels like enough, and even at the end of the book, Meyer questions his emotional responses to his patients.

Meyer details the fear doctors felt in the ER and that they brought home with them; the fear of infecting their families, or that they themselves are infected and don’t know it yet. As doctors start to become sick with Covid-19 — or have family members who get seriously ill or die — what was once professional becomes very personal.

Though the book is a bit choppy in places, with frequent chronological shifts, the authors consistently place the pandemic in a larger context: the community, the sociopolitical environment, the systemic failings. They discuss the inequities of the health care system, both in the Bronx and in the U.S. as a whole, and how Covid-19 exacerbated them. While the book mostly avoids politics, the authors make note of the reality that, early on in the pandemic, “the biggest city in the richest, most powerful nation in the world is on its knees.”

The book ends in the fall of 2020, making it more of a snapshot in time rather than a comprehensive chronicle of the pandemic. When the book leaves Meyer, he doesn’t yet know that the fall would bring more outbreaks and school closures — and many more deaths. Even with the vaccine being rolled out, the winter of 2020 and the first part of 2021 would bring plenty of heartache. He has no way of knowing about vaccine refusal and emerging variants, not to mention infection numbers returning to those of the early days of the pandemic.

All of this raises the question of whether the book would have benefited from some more time. Was there enough space for Meyer to fully examine his experiences while still in the thick of it? Would the story have been better told from an outside, more objective point of view? How have the administrators and medical staff of Montefiore adjusted to cope with the ups and downs of the crisis? Questions like these inevitably make the narrative feel unresolved, even as it succeeds as a vivid first-hand account of a doctor’s daily struggles on the front lines.

But that may be the authors’ primary goal. “We may not be able to stop the next pandemic,” Meyer concludes, “but we can be better prepared if we don’t forget this one.”

Jaime Herndon is a medical and parenting writer who also writes about popular culture in her spare time. Her work has appeared in New York Family, Book Riot, Fiction Advocate, Today’s Parent, Motherly, Healthline, and Health Union, among other publications.