Planting Trees to Offset the Legacy of Racist Housing Policies

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story has been updated to correct several inaccuracies. A full accounting of changes made can be found here.

When Dovie “DJ” Arnold plants trees in Richmond, California, the neighborhood cheers him on. Older residents try to tip him and bring him water. Arnold, who is Black, works with Groundwork Richmond — a local chapter of a national network aiming to improve greenspaces in low-resource communities. He works in many of the same neighborhoods where his grandparents and other families were pushed when they moved to the city following war-effort jobs in the 1940s.

The neighborhoods, a result of segregationist policies, have been long passed over for green improvements. “Seeing people happy with the results of what we do,” Arnold said, “it’s really heartwarming.”

In the United States, Black and Brown neighborhoods, like those where Arnold works, face higher pollution than their White counterparts. According to new research, the ones that were segregated also have fewer trees. This disparity was made possible by a series of racist policies instituted in both federal and local government agencies that relegated the unsavory parts of cities to Black neighborhoods.

A growing body of scientific research focuses on one of those housing policies, redlining, and how it continues to shape modern health and environmental outcomes. Redlining dates to the 1930s, when the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) designated many Black and Brown neighborhoods as high risks for financing, outlining the areas in red on maps. Mostly White neighborhoods, meanwhile, were usually lined in green and considered good investments. (The U.S. outlawed redlining in 1968 through the Fair Housing Act.)

Unlike other Bay Area cities, Richmond — which had a population of less than 25,000 back in the 1930s — wasn’t itself redlined by the HOLC. But it was still subject to policies that resulted in housing segregation, and has suffered a similar long-term fallout when it comes to health and environmental disparities.

Out of all of the past segregationist housing policies, redlining is particularly illuminating because the maps left behind by the appraisal process make it relatively easy to study, said Joan Casey, an environmental epidemiologist at Columbia University who co-authored one such study, published in Environmental Health Perspectives in January. Research like Casey’s has shown how the policy continues to shape the landscapes of U.S. cities.

“Oftentimes we’re describing inequitable distributions of resources, or increased levels of pollution in communities of color,” Casey said, which doesn’t point to why these inequities exist. “So assessing historical redlining,” she added, “helps fill in the pieces of this puzzle.”

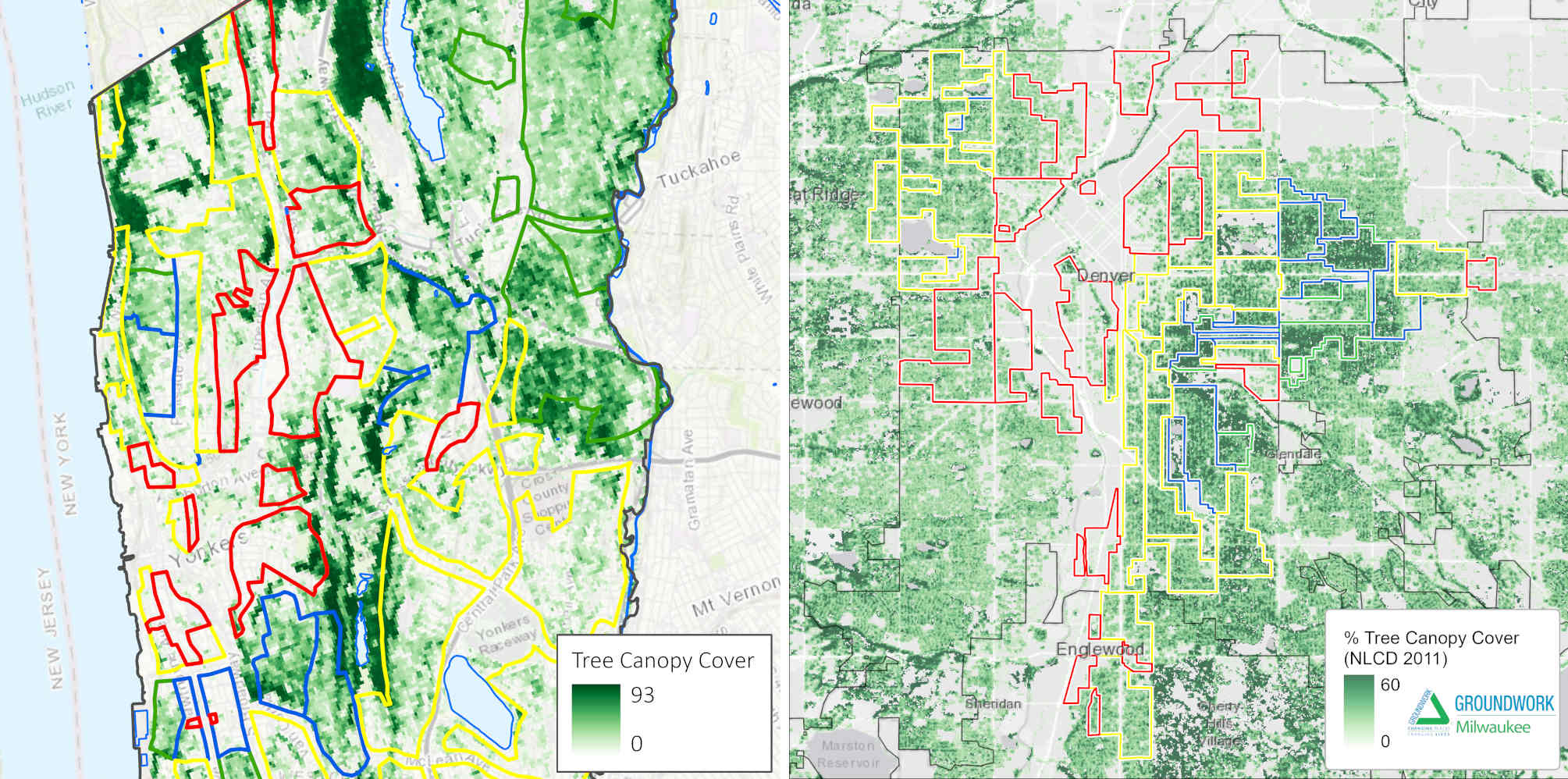

Previous research has shown that formerly redlined neighborhoods are on average 4.7 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than non-redlined ones, and have higher rates of preterm births and asthma hospitalizations. Most often, this work has highlighted health and environmental outcomes between redlined neighborhoods, graded as D by HOLC appraisers, and neighborhoods outlined in green, which were given an A grade. (Neighborhoods in between received blue for the B grade and yellow for the C grade.)

For their January study, Casey and her collaborators took a different approach. To best isolate the effects of redlining as a policy, they focused on neighborhoods that were redlined compared to neighborhoods with similar racial and economic demographics that, for unknown reasons, were graded C instead.

In order to compare the communities, the researchers used a measurement that estimates vegetation based on how much near-infrared light an area reflects — the more light reflected, the more plant cover. The researchers used this measurement, called the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), while comparing old redlining maps with satellite imagery of greenspace in 102 cities. The redlined neighborhoods had a nearly 8 percent lower NDVI score than neighborhoods outlined in yellow, after the researchers eliminated demographic outliers. Yellow neighborhoods, in turn, had a 10 percent lower NDVI score than neighborhoods in blue.

“We compared those communities that had the same probability of getting the Grade D or the redline, and found — flash forward all the way to present day — the ones that actually got redlined have lower greenspace,” Casey said.

For Casey, comparing greenspace between D and A neighborhoods would do little to show the fallout from redlining, since other factors could explain the difference in the number of trees and parks. Wealthy residents, for instance, are more able to pay for local beautification and to support existing tree cover. By comparing more similar neighborhoods, she says her team’s data are both more interesting and more damning of the policy. While other forms of disinvestment may have followed, redlining is the factor that initially placed some neighborhoods on a path that led to less greenspace in the next century.

Other researchers see Casey’s study as providing a link between current conditions and historic causes. Jennifer Wolch, a professor of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley, has also studied greenspace disparities, focusing on urban park space across the U.S. In a 2005 study on park distribution in Los Angeles, for instance, she found that neighborhoods that were at least 75 percent White had nearly 19 times more park space per capita than those that were at least 75 percent Black, and 53 times more park space per capita than neighborhoods that were at least 75 percent Latino. Wolch used current neighborhood demographics rather than historic housing policy, but her results show the same trend as Casey’s team. Wolch said both datasets are complimentary, and help explain how formerly redlined neighborhoods appear today.

“It’s important to look at the historical context of present-day circumstances — very important. Cities are sticky, they don’t change really super fast,” Wolch said. Policies like redlining, she added, left their mark on neighborhoods in ways that don’t vanish once the policy itself is made illegal: “The historical shadow on these places is really deep.”

Although Richmond was never formally redlined, housing policies throughout the city’s history have left similar marks. In 1940, only 270 Black people lived in Richmond, but thousands moved to the area to work the shipyard when the U.S. entered World War II. By 1945, the Black population had reached 14,000. Richmond was unable to provide living space for the workers, so the federal government built temporary housing. The housing projects were explicitly segregated; Black workers were placed closer to the shipyards, which became polluted with the pesticides DDT and dieldrin that were packaged and shipped from the area. There was other pollution, too. “Much of the Black population was always focused around maritime industry,” said Darrell Owens, a Bay Area policy analyst and housing advocate. “Which actually was a problem, because that’s where a lot of munitions were located. And that’s where dumping was located.”

As Richard Rothstein, a fellow at the Economic Policy Institute, a worker-focused think tank, argues in his history of segregation, “The Color of Law,” because Richmond was essentially all White before the war, the federal government’s role in housing directly established segregation in the city.

North Richmond, where Arnold’s grandparents lived at one point, had sprung up as an offshoot to the city where Black, Latino, and Asian families could live when they could not find housing in Richmond proper. The neighborhood did not have discriminatory zoning, but also lacked basic services like streetlights and paved roads because the city of Richmond was not responsible for its upkeep.

After the war, the federal government subsidized suburban neighborhoods on the express condition that they would be White only, providing examples of restrictive covenants that mandated home buyers be of the same race as the seller. The Federal Housing Administration’s 1938 Underwriting Manual stated that including a restrictive covenant would make projects more likely to get government loans. Rothstein writes that in Richmond, this meant when White families moved to newly-built suburbs like Rollingwood, Black people were left in the same public housing built for the war, closer to pollution from industry and without federal money to help them buy their own homes. By 1950, the war projects housed more than 75 percent of Richmond’s Black population.

In the decades after the war, the Black population in Richmond expanded into more neighborhoods, and White families continued to leave the city in favor of segregated — and green — suburban neighborhoods. In 1950, 80,000 White people lived in Richmond. By 1960, that number fell to 56,000. Meanwhile, Latino and Asian families moved to Richmond, now comprising about 42 percent and 15 percent of the city’s population, respectively, drawn by some of the most affordable housing prices in the Bay Area.

When the state needed to find a place for environmentally damaging and politically unpopular projects, those projects often ended up in the communities of color. In the 1950s and 60s, residents of some of San Francisco’s wealthier neighborhoods were able to stop the construction of a maze of freeways that would have divided the city. Richmond did not have the same political power, and is surrounded by interstate highways to this day, part of a national trend of freeway construction that isolated communities of color and polluted them with exhaust fumes. Today, Richmond is crisscrossed by rail lines, and is home to an oil refinery.

“When the constituents are more Black people,” Owens said, “the environmental concerns are not taken as seriously.”

Groundwork Richmond and locals are working to build a more hospitable environment. Arnold started working for Groundwork Richmond in May of 2019 as an urban forestry technician, planting and maintaining trees across the city. Now he keeps track of the data on tree location, age, and maintenance needs for all the trees the organization has planted.

“It started off just because I needed a job, but the more I got into it, it is important,” Arnold said. “We do need these trees. They serve a really big purpose.”

The trees aren’t just a matter of aesthetics. Greenspace is associated with reduced mortality rates, especially due to respiratory disease, which can offset some of the pollution burden from the freeways, trucking, and the oil refinery that give Richmond some of the worst air quality in the Bay Area. In the mortality rate study, researchers note that sociodemographic factors may have influenced their mortality data, hinting that greenspace is only one part of the urban geography that determines which places are the designed to keep people healthy. Mental health also improves with greenspace. A 2013 study in the journal Public Health found greenspace, including both parks and dispersed city plants, is associated with reduced anxiety and mood disorders in residents of Auckland, New Zealand. By reducing energy costs and offsetting the effects of the urban heat bubble caused by concrete and asphalt, trees also make neighborhoods more climate resilient, providing refuge from the physical and mental stress of heatwaves in a paved landscape.

“I think there’s a very clear environmental justice issue,” Wolch said. “We’re used to thinking about environmental justice as disproportionate impact from exposure to toxic waste or pollution of various kinds. But it’s also a disproportionate lack of access to good things in the environment.”

Arnold and Groundwork Richmond are working to bring those good things to their city, collaborating with other nonprofits to turn a rail line built in the early 1900s into a strip of green cutting across Richmond. The tree team plants individual trees along city streets, and knocks on doors to see if residents want a free tree in their yard. Lorenzo Plazola, who runs the tree planting program, says the trees have a way of going viral.

“Sometimes we’re just driving around a neighborhood and just talking to people, and you know ‘Hey, would you like a tree?’” Plazola said. “People really take to it. In fact, sometimes we’re planting a tree and people will just come up and say ‘I want one. I saw my neighbor’s got a really nice tree. I want one just like that.’”

Groundwork Richmond, which has received funding from the city and the National Park Service, focuses on the neighborhoods lacking resources — the ones surrounded by railways and industry, that are hotter and more polluted. Plazola is from San Leandro, another heavily Latino part of the Bay Area 25 miles south. He recognizes other similarities.

“Even though I grew up outside of Richmond, every other person had asthma. And that comes from somewhere,” Plazola said. He, too, was raised between freeways, and feels fortunate to have escaped the disease. “I grew up landlocked between the 580 and the 880, so I just got lucky.” Richmond is sandwiched between 80 and 580 as well, Plazola notes.

Alongside other nonprofits, Groundwork Richmond helped build Unity Park as a part of the Richmond Greenway project, which aims to turn an early 1900s rail line into a strip of green cutting across Richmond. Members talk about the park in this 2019 video.

Video: Groundwork USA

Casey, the Columbia University researcher, says she hopes her team’s work will make lawmakers and voters consider the long-term outcomes of housing policy proposals. “This is an example of how policy decisions — from now almost 100 years ago — are still impacting environmental quality and health in communities today,” she said. “We wanted to be able to make the point that policy decisions really matter. And things that we enact now could reverberate and have effects on people 50 years down the line.”

But Wolch says new housing policy will be needed to get the most from Groundwork Richmond’s environmental gains. As neighborhoods become greener, property values go up, and locals can be pushed out before they receive any benefit from the new green spaces. In New York City, for instance, an elevated park called the High Line that was built in 2009 raised nearby property values by 35 percent, displacing residents from the area. This has led some critics to caution against flashy greening projects out of fear that it will trigger gentrification. For Wolch, a middle ground is possible. Communities, she said, need affordable housing policies that can combat gentrification and keep people in their homes so that environmental justice work can truly provide for them a healthier future. Local input, Wolch added, is key. Greening projects planned by outside investors tend to bring more people into neighborhoods than projects locals develop for themselves.

When Plazola started working at Groundwork Richmond in 2015, the organization’s big project was building what would become Unity Park in central Richmond, a 12-acre park that Groundwork and other groups planned out and built with input from the community. The piece of land used to be an abandoned lot. Now there’s a playground, a basketball court, and trees and bushes growing along garden pathways. Sandwiched between the sheet metal walls of neighboring buildings, murals depict scenes of clean blue water and people walking in the forest.

“We’re doing this to try to bring the community together, and creating this whole transformation from within,” Plazola said. “We’re all working here together, and doing this thing for Richmond, by people from Richmond.”

UPDATE: An earlier version of this story strongly implied that Richmond, California, was redlined by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation in the 1930s. Richmond was not redlined, although other housing policies in the city over the years led to environmental and health disparities similar to those found in formerly redlined communities. The headline and subheadline have been changed to correct the same error. An earlier version of this story also included a photograph of Richmond with an overlay of an artistic interpretation of a redlined map. This map has been removed. (Return to top)

Joe Purtell is an independent journalist interested in climate, ecology, and geography. He lives in Oakland, California.