Before the arrival of Covid-19, Alzheimer’s disease was the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States, killing more than 121,000 people in 2019. Around 6 million people, most aged 65 or older, live with the disease in the U.S. Until this week, a handful of drugs could ease their symptoms, but no drug had been approved to reverse the underlying causes — which remain murky.

On Monday, though, the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a new Alzheimer’s drug called aducanumab, developed by the pharmaceutical company Biogen. But whether the drug works remains contested, and the decision to approve it has set off a fierce debate over the ways that commerce and advocacy might influence which drugs reach market. The dispute has pitted Alzheimer’s advocacy groups, the FDA, and Biogen against a chorus of researchers who say it’s still unclear whether aducanumab offers any benefits at all.

The stakes of getting the decision wrong are high: The drug has significant side effects, and analysts warn that the high wholesale cost of aducanumab therapy — $56,000 per year — could strain the health care system and raise insurance premiums.

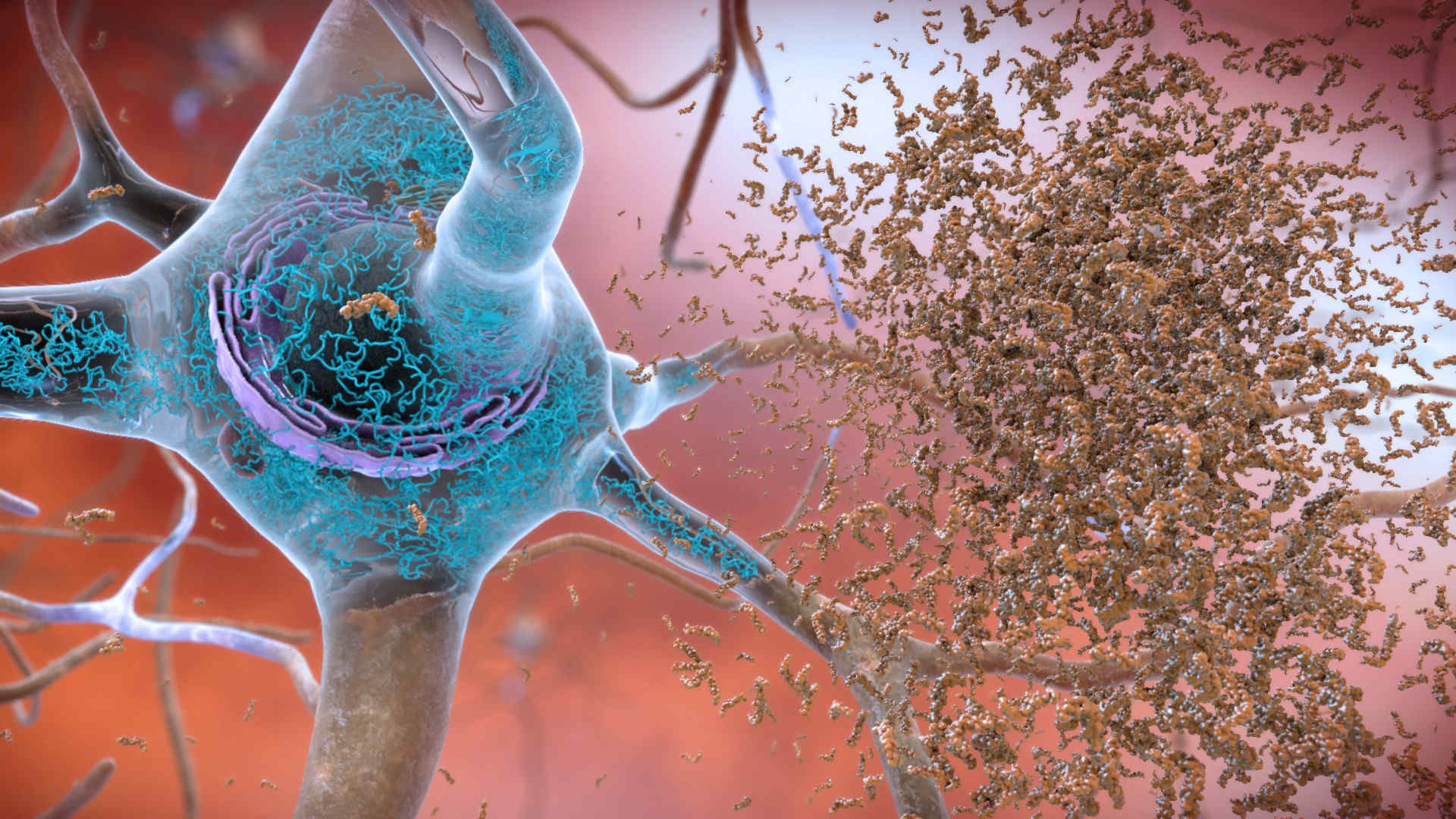

Aducanumab works by attaching to proteins that build up in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, called amyloid plaques. The drug flags those proteins for the immune system, which then clears them away. Researchers are divided on whether such plaques actually cause Alzheimer’s symptoms. And, so far, the evidence is scant that aducanumab works: Of the two phase 3 studies Biogen presented to the FDA, one did not find cognitive benefits. The other also initially seemed to have shown no benefit — until the company reexamined the data. By late last year, Biogen was describing the work as “a robust and exceptionally persuasive study.”

In November 2020, a panel of experts convened by the FDA reviewed the data. The group did not find the evidence so persuasive: Asked to judge whether the study showed that aducanumab is an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s, none of the 11 experts voted yes.

Seven months later, the FDA gave the drug the greenlight anyway, under an accelerated approval process that requires Biogen to continue studying aducanumab’s efficacy as more patients receive treatment. While the company must finalize a plan for the study by next August, it has until 2030 to submit a final report to the FDA.

The unusual decision to ignore the advisory panel, some critics charge, had less to do with the science, and more to do with the converging desires of Biogen — which stands to make billions by bringing the drug to market — and patient advocacy groups, which are desperate for some kind of cure and hopeful the approval will spur further research.

After the decision to approve aducanumab, three members of the FDA-convened panel that advised against approval resigned from their posts in protest. In an op-ed for STAT, the Alzheimer’s disease researcher Karl Herrup and an undergraduate student, Jonathan Goulazian, accused Biogen of responding to market forces more than scientific evidence in its push to get approval for the drug. “The message is simple: Wall Street wants to keep the good news coming,” they wrote. “Don’t ever let them smell your fear.”

Still, groups representing Alzheimer’s patients celebrated the announcement as a hopeful step: In a statement from the Alzheimer’s Association praising the ruling, Maria C. Carrillo, the organization’s chief science officer, said the decision “ushers in a new era of Alzheimer’s treatment and research.” (Last year, the organization received six-figure donations from Biogen and Eisai, a partner company.)

At the FDA panel in November, one advocate, UsAgainstAlzheimer’s cofounder George Vradenburg, had begged the group to give the drug a shot. “If we wait for the perfect drug or perfect data,” he said, “we will descend further into the grip of this awful disease.”

Also in the News:

• For weeks, critics have pressed the U.S. government to send surplus doses of Covid-19 vaccine to countries that desperately need them. Last week, the White House announced it would share 80 million doses with the world, the majority to be distributed by COVAX — a global vaccine-access program backed by the World Health Organization. Now the donation is getting a significant boost. On Wednesday, sources told The Washington Post that the Biden administration plans to purchase 500 million doses of Pfizer’s jab to donate to mainly low- and middle-income countries through COVAX. The first 200 million doses are set to deliver this year, with the remainder following in 2022, according to The Post. And on Thursday, President Biden confirmed the reports, announcing the donation at the ongoing G-7 summit in Britain. The move could help address the widening global disparities in vaccine distribution. As The Post noted: “The gap between vaccines haves and have-nots is vast. More than half the populations in the United States and Britain have had at least one dose, compared with fewer than 2 percent of people in Africa.” (The Washington Post)

• A former Wisconsin pharmacist convicted of trying to destroy more than 500 doses of coronavirus vaccine has been sentenced to three years in prison. In January, Steven R. Brandenburg, a hospital pharmacist who worked at the Aurora Medical Center in Grafton, near Milwaukee, admitted to intentionally removing 570 doses of the Moderna vaccine from the refrigeration required to keep them viable and leaving them out overnight. Brandenburg — a self-described conspiracy theorist — told police that he believed the vaccine would harm patients if injected. A coworker ultimately returned the vials to the fridge before the vaccine’s 12 hours of viability were up. While Aurora soon recognized the problem and tossed most of the tampered doses, 57 people had already received shots from the supply. Those doses seem to have still been effective, but they caused anxiety among those who received them. In a statement, Brandenburg said he felt “great shame” about his actions. Prosecutors have found evidence that, before tampering with the vaccines, Brandenburg had attempted to persuade coworkers not to receive other immunizations. (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel)

• A new report from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission contains grim news about one of the state’s beloved marine animals: At least 761 manatees died in the state over the first five months of this year, more than were lost in all of 2020 and more than 10 percent of Florida’s total estimated manatee population. In explaining the sudden jump in deaths, experts cited an ecological chain reaction they say was likely triggered by toxic runoff from fertilizers and human waste. They believe an influx of the nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich runoff into the Indian River Lagoon — a popular manatee feeding ground — has fueled algae blooms that soak up vital oxygen and block sunlight from the lagoon floor, killing sea grass that manatees use for food. “The fact that manatees are dying from starvation signals there is something very wrong with the water quality,” Jaclyn Lopez, Florida director for the Center for Biological Diversity, told The New York Times. But the commission’s report also suggests that other factors are at play, including boat collisions, which were responsible for 49 of the manatee deaths. Manatees are considered a bellwether for the state’s aquatic ecosystem more generally; that their numbers are plunging, experts say, suggests the entire ecosystem is in decline. (The New York Times)

• According to an article published in the journal Biology Letters this week, healthy canaries displayed an immune response when they observed, from afar, other canaries that were infected with a bacterium. The finding suggests that the uninfected birds’ immune systems reacted to visual stimuli without any direct contact with the pathogen. Ashley Love, a biologist at the University of Connecticut and the lead author of the paper, conducted her research while still a graduate student at Oklahoma State University, using Mycoplasma gallisepticum to infect birds that were within sight of uninfected birds. When Love and her colleagues tested healthy birds’ blood, the researchers found that some had high levels of cells known as heterophils, which typically surge in response to an avian infection. The canaries’ blood also had elevated levels of complement molecules, which are used to fend off bacteria. The finding raises questions about whether that preemptive immune response actually improves the birds’ ability to resist an invading pathogen. To test that possibility, Love now plans to expose observing birds to Mycoplasma bacteria to see if the visual warning gives them an edge in fighting the infection. (The Atlantic)

• Carbon dioxide — a major driver of global climate change — climbed to record atmospheric levels this spring, according to a new report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In fact, the agency said that the new levels — about 419 parts per million — are worryingly similar to atmospheric CO2 levels more than 4 million years ago, in the Pliocene era. During the Pliocene, sea levels were more than 70 feet higher than they are today, and lush forests covered much of the Arctic. Researchers also noted that the carbon dioxide readings taken in May, at an observatory in Hawaii, are the highest recorded since such measurements began in 1958. Some experts expressed dismay that the increase came despite a period during which the Covid-19 pandemic depressed human activities, from air travel to heavy traffic to factory production, that are major producers of the greenhouse gas. Further fossil-fuel based activities, which generate vast amounts of CO2, are expected to accelerate this year and lead to even higher levels of the gas in coming months. Scientists urged countries to accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels: “If we take real action soon, we might still be able to avoid catastrophic climate change,” said one NOAA researcher. (Multiple sources)

• And finally: Scientists at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia believe that they have discovered a new population of pygmy blue whales in the Indian Ocean. The study, published in Nature Scientific Reports in April, has been getting attention after UNSW issued a press release this week. According to the university, the discovery happened when scientists analyzing sound data observed an “unusually strong signal” that appeared to be whale song. The sound data was collected through the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO), which deploys sophisticated microphones in the ocean to detect underwater nuclear bomb tests, but also shares recordings with marine researchers. After closely studying the frequency and nature of the signal, the scientists concluded that it belonged to a previously unknown group of pygmy blue whales. The researchers have not been able to give an estimate on how many whales live in this group. There have not been any sightings of the potential new population, but if that were to happen, it would become the fifth confirmed group of pygmy blue whales in the Indian Ocean. (Newsweek)

“Also in the News” items are compiled and written by Undark staff. Deborah Blum, Brooke Borel, Lucas Haugen, Sudhi Oberoi, Jane Roberts, and Ashley Smart contributed to this roundup.