Growing Pains: Why Covid’s Disruptions Take a Heavy Toll on Teens

For 16-year-old Zuri Arreola, life today differs in almost every way since the Covid-19 pandemic began more than a year ago. Last year, she was a gregarious high school sophomore, passionate about acting and dancing. Today, Arreola rarely if ever sees her friends and has no time for hobbies. “I was so social, and now I feel so — I don’t know, introverted, awkward,” she says. Her public school in Los Angeles has been remote since last March. The online classes, which she finds exhausting, sometimes give her throbbing headaches.

Because her father’s income as a carpenter fell during the pandemic and her family is ineligible for stimulus payments — her parents are undocumented — Arreola recently started working at McDonald’s after school and on the weekends to help support them. She works as many as 34 hours a week, with shifts starting as early as 5 a.m. “It’s a blessing, but it’s also another weight on my shoulders,” she says. Sometimes, she adds, customers verbally abuse her, especially when she asks them to put on masks so that she — and they — can stay safe.

When Arreola does have time to herself, she has virtually no energy left to do anything. “I just want to be home laying down,” she says. Occasionally she checks social media, where her heart breaks when she sees pictures of her old friends with new friends they have made when they’ve spent time together outside of school. Arreola knows she is struggling, but when she asked her parents to help her find an online therapist, she says they said they weren’t comfortable with the idea. So Arreola waits for the pandemic to end, hoping that life might one day feel normal again — and hoping that her friends haven’t left her behind for good.

|

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive. |

The coronavirus pandemic has been hitting adolescents hard. During the teen years, friendships matter more than almost everything else: The pull that teens feel towards their peers naturally pushes them away from their parents, sparking a period of independence that, according to the well-known German-American psychologist Erik Erikson, is crucial to their development into healthy adults. Adolescence should be a time for teens to cultivate “a better sense of themselves, and how they relate to their friends and the world around them,” says Robin Gurwitch, a psychologist and professor at Duke University Medical Center.

But this year, teens have been forced to stay home and avoid real-world interactions with their friends. They have had to spend their days denied of their deepest needs while, in some cases, taking on more responsibilities — yet without many of the emotional supports they had in the past. Data suggests that the pandemic is putting teens at greater risk of parental abuse, and some have also become targets of discrimination. In a study published last August, researchers from the University of Maryland reported that 77 percent of the Chinese-American young people they surveyed had experienced racism during the pandemic. Native American, Black, and Hispanic teens are also grieving the loss of family members at devastatingly high rates; Arreola’s grandfather in Mexico passed away from Covid-19 on her birthday.

It’s no surprise, then, that teen mental health has been crumbling across the country. From March to October 2020, the proportion of U.S. emergency room visits among 12- to 17-year-olds attributed to mental health problems increased by 31 percent compared to the same period in 2019, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In a November 2020 survey of just over 1,900 U.S. teens and young adults by Mental Health America, a nonprofit organization that works to address the needs of individuals with mental illness, only 26 percent of youth aged 14 to 18 agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “I feel hopeful about the future.” (An even smaller percentage of LGBTQ teens and teens of color did.)

And in a study posted online in February that has not yet been peer reviewed, researchers analyzed data from a dozen ongoing international long-term studies on youth mental health. They found that depression symptoms in kids aged 9 to 18 increased by 28 percent in the first six months of the pandemic, and that symptoms were most pronounced among multiracial teens and those in lockdown.

For some adolescents, feelings of hopelessness can morph into thoughts of suicide. “Suicide attempts have gone up, and they’ve gone up even among younger kids,” says Robyn Silverman, a North Carolina-based child and teen development specialist. Although data on the impact of the pandemic on suicide rates is still preliminary, a recent study in the journal Pediatrics found that the rate of suicidal ideation and attempts at suicide in one pediatric emergency department did increase last spring and summer. And in Clark County, Nevada, 18 teens took their lives from March to December of 2020, according to reporting from The New York Times — twice as many as over the same period the year before.

At least one additional Clark County student died by suicide at the beginning of 2021, and the deaths compelled the local school district to re-open in the hopes that getting kids back to school would help. Across the nation, many other schools are in the process of reopening, too, and the issue has been contentious, with fierce debates over the balance between Covid-19 safety and teen well-being.

It’s hard to know what the long-term effects of the pandemic will be on American teenagers. For any individual adolescent, it will almost certainly depend upon the particulars of their background and circumstances. But experts say teens’ lives will undoubtedly be shaped by the many months of isolation, fear, and loss, as well as by the difficult predicaments they face at school and at home.

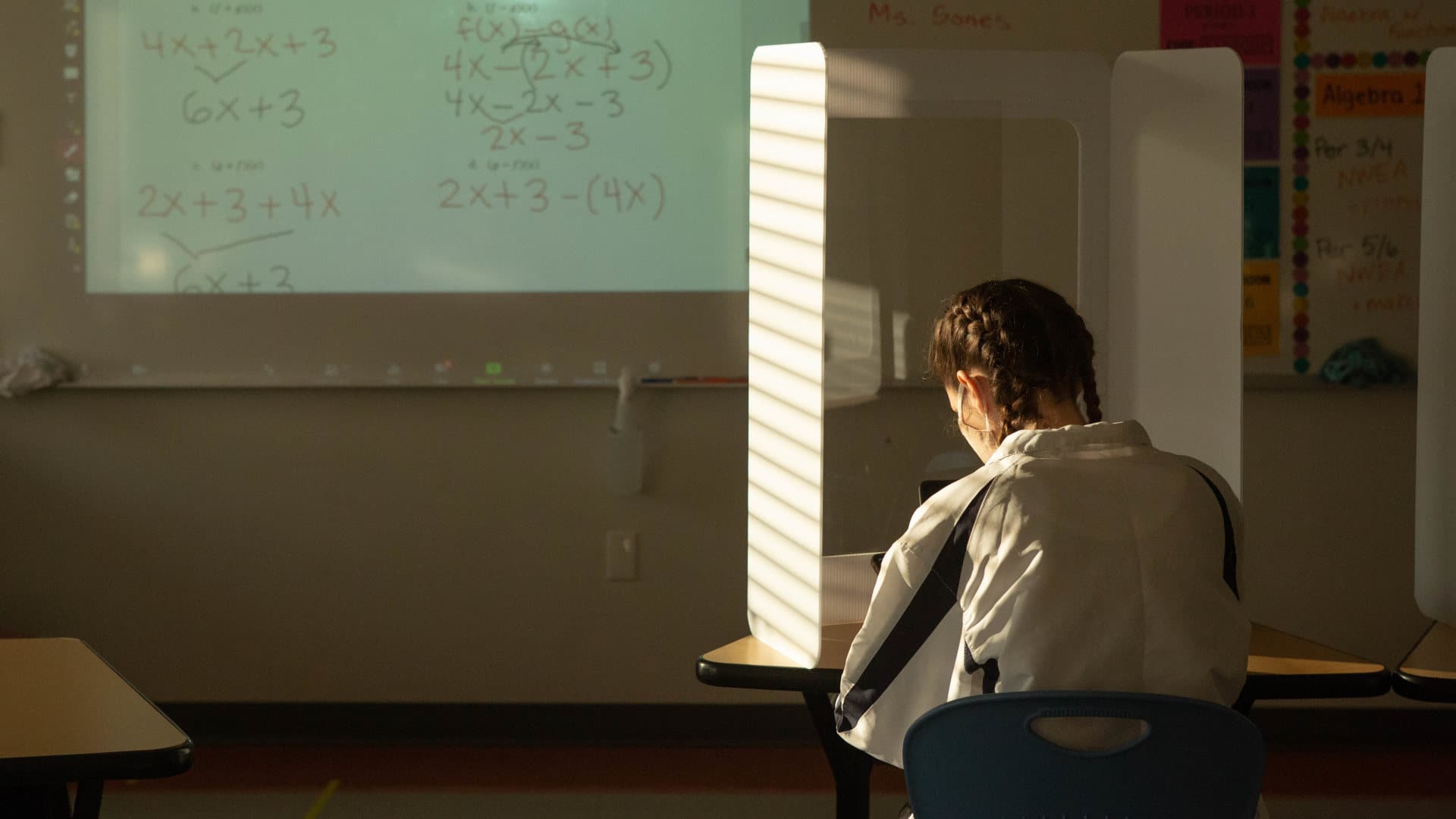

For teens, one of the hardest things about the pandemic is that even though they are still expected to learn, school has changed in ways that make it very hard to teach them. According to the School Opening tracker run by Burbio, a data company that tracks school data from 35,000 U.S. schools in all 50 states, 49 percent of high school students were attending remotely or on a hybrid schedule as of this week.

Remote school is difficult for many reasons: It’s hard to connect with peers and with teachers over a computer. It’s difficult to stay focused in lessons. Staring at a screen all day is exhausting. “It’s so much of their time, it’s so much of their day — and it’s so hard on them,” says clinical psychologist Lisa Damour, a senior adviser to the Schubert Center for Child Studies at Case Western Reserve University and co-host of a parenting podcast.

One problem is all the distractions. After the pandemic began last year, the California Partners Project, a nonprofit that champions gender equity, and the Child Mind Institute, a nonprofit in New York that supports children with mental health disorders, interviewed and collected detailed diary entries from more than 40 teens aged 14 to 17 living in California. Every teen reported using non-school-related devices and apps like Snapchat and TikTok during their online classes.

“Students can just be on their phones, watching soccer, playing video games all through class, and not learn a single thing,” says Ben Ballman, a high school senior in Potomac, Maryland who in 2019 co-founded DMV Students for Mental Health Reform, a nonprofit organization run by high school students from the Washington, D.C. area. “I could sit through a class and not learn anything, and then have a test online and be able to look up all the answers, and not retain a single ounce of knowledge.”

Even when teens want to focus, many can’t. Gwen Larsen, a high school English teacher in Long Beach, California, says that not all of her students have an environment conducive to listening and learning at home. Sometimes, when she teaches and her students aren’t muted, she says: “I hear five other siblings on Zoom, I hear the TV, sometimes I hear parents fighting.”

Another problem is the physical distance from peers. Michelle Rojas, a high school senior in Arlington, Virginia and a co-founder with Ballman of the D.C.-area student group, says that she feels less motivated in remote school in part because she’s not fueled by the competition she would feel when surrounded by classmates. “The social pressure can motivate you,” she says. “There isn’t really that in a virtual environment.”

Phyllis Fagell, a middle school counselor at the private Sheridan School in Washington, D.C., agrees that the teens she sees aren’t learning as much online. “So many grades are slipping,” she says. “There’s so much going on. It’s easier to fall through the cracks.”

And that’s just the kids who are able to show up to remote classes. Arreola says that many of her classmates stopped attending remote school entirely. Some didn’t have the equipment they needed — an issue that has plagued school districts across the U.S. Last spring, Arreola and her sister, now a high school senior, only had one temperamental laptop in their home to share, and their internet access was spotty. “We requested an internet hotspot from our school, but they had run out completely,” she says. A few weeks later, they were able to get two laptops and a hotspot from InnerCity Struggle, a nonprofit that serves L.A.’s Eastside neighborhoods, but she says that some of her friends have not been so fortunate.

Another problem with remote school is that it cannot offer the mental and emotional supports that are built into the school environment. “So much of how we take care of kids is being in their traffic patterns,” Damour says. “They run into us in the hallway or they see us in a health class or they know where our office is and they sort of swing by casually.” When school is remote, students can usually still meet with school counselors virtually, but only if they request a formal appointment — which students don’t always do, even when they need help.

According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 15.4 percent of American 12- to 17-year-olds received mental health services at schools in 2019 — a 27 percent increase from 2009 — and many of these students have undoubtedly been unable to access these same services during the pandemic. The same survey for 2020 won’t be available until summer, but experts expect a drop.

The social aspects of remote school are difficult for adolescents, too, and not just because they don’t get to hang out with their friends or feel the rush of peer competition and collaboration. In a typical classroom, students all face the same direction, so they can feel connected but not like they’re being scrutinized. Zoom creates an entirely new dynamic, with everyone face to face all at once. According to Damour, some students feel so self-conscious that they turn their cameras off, which often makes them less engaged.

Other students feel the responsibility to keep their cameras on to support their teachers, but because they are among only a handful of students visible, they feel like they’re being stared at and judged. “All of the energy and fun that comes with being in person with one’s peers is absent, and all of the scrutiny and self-consciousness that comes with being with one’s peers in person is amplified,” Damour says.

Remote school can be especially difficult for teens with disabilities and neurodevelopmental differences. Thirteen-year-old Nick Kemmerer, who is on the autism spectrum, thrived when he went to in-person school — so with the pandemic and the “sudden loss of access to his friends, his teachers, his routine — it was really jarring,” his mother Brigid Kemmerer told Undark in an email. “I was taking my kids on walks every day, and I will never forget the moment that Nick burst into tears and started yelling. He was screaming in rage, sobbing, telling me he wanted to kill himself if he had to live like this. It was awful. I can still hear his little voice. It was terrifying and heartbreaking and I didn’t know what to do.” (She called her pediatrician that day and got him help, and Nick returned to school in person in the fall.)

Even when teens do get to attend school in person, they can find navigating the new health safety rules devastatingly hard. In middle school, students are often placed into small learning groups, or pods, and are unable to freely interact with their friends. “I’m hearing all the time, ‘Oh, my best friend’s in another pod,’ or, ‘All the kids I like to hang out with are in another pod,’” Damour says.

Fagell agrees that these forced separations can be traumatic. “You can literally be looking longingly across to the other side of the playground and see your closest friends hanging out without you,” she says. This pod structure also means that students don’t get to interact with all of the people they would usually see in school hallways each day. Many teens interviewed as part of the California Partners Project report said they missed not only spending time with their close friends, but also the serendipitous encounters they used to have at school with students they didn’t know very well, which are virtually nonexistent now even if they have in-person school.

The collective struggles teens face can have devastating consequences. Last fall, Spencer Smith, a 16-year-old sophomore in high school in Brunswick, Maine, began attending school on a hybrid schedule. Most of the time, he took classes online, but he would go in person once a week, where school was nothing like it normally was. He was required to sit in a cubicle alone and work on a laptop. While there, the students “weren’t allowed to communicate with their friends,” his father, Jay Smith, told Undark.

According to Smith, Spencer didn’t feel like he could talk to his friends when he walked to and from school, either, because some parents would chastise students if they saw them walking too close to each other. “He was the type of kid that never got in trouble. So he tried to make sure he was off to the side with nobody around him,” Smith says, adding that Spencer had seemed like a happy kid before the pandemic hit. But because Spencer felt he couldn’t hang out with his friends, Smith says, he also felt as though he had lost them. Spencer was torn between doing what he felt was right and attending to his own social needs; his needs lost out.

The teen years center around many school activities and milestones, too — which due to the pandemic have been cancelled or changed in disappointing ways. Smith says that missing out on football may have been the last straw for Spencer. He had spent all summer training to play, but when school started back up, he was told that only 7-on-7 football — in which only seven players, rather than the normal 11, play on each side in shorter games — was being offered, and he quit. He “started taking naps in the afternoon, and he had nothing to do,” Smith says. Last December, Spencer died by suicide.

No one yet knows how teen suicide rates last year and this year will compare to those from years past; a research letter that recently appeared in the journal JAMA Network Open showed that suicide rates across all age groups in Massachusetts were no higher during the early months of the pandemic than over the same period in previous years. But national data have not yet been published and “youth suicide has been on the rise over the last 10 years,” says Rebecca Leeb, a developmental psychologist and epidemiologist at the CDC. “It may be exacerbated by the pandemic.”

Outside of school, the isolation spurred by the pandemic is another key driver of teen despair. Social gatherings are few and far between — and even when teens are able to see their friends in person, many feel constrained by the rules of social distancing and mask-wearing.

“They miss touching their friends,” Fagell says. They also miss physical experiences like huddling together over a phone, playing video games together, and roughhousing, as well as the kinds of shared experiences that serve as an important source of connection and conversation. Teens love to talk with each other about what happened during a game, or who made a funny comment in class — and now they don’t have the shared experiences to spark these conversations.

“Keeping in contact with my friends is definitely tough because it’s the little simple parts of life — being connected, talking with a friend that’s sitting next to you — it’s those little things that help us get by, help us put a smile on our face,” says 19-year-old Alondra Lara, a freshman at California State University Fullerton who is living with her parents because classes are remote. “And that’s something that technology can’t really do.”

Although adolescents connect with each other over the phone, Zoom, and social media, these venues are no match for being together in person, and they also create new challenges. “Everyone is having a harder time interpreting social cues, whether they’re doing it from a distance through a screen or through a mask,” Fagell says. Normally, if two teens get in a fight over social media, they have the opportunity to work it out in person at school the next day. But now, if a teen is in virtual school and his best friend blocks him on social media, he has no way to figure out what happened and smooth things over. “All kids right now are feeling like their friendships are more mercurial and more fragile,” Fagell explains.

Research finds that loneliness is a powerful driver of poor mental — and even physical — health. A recent review of studies of adolescent mental health found that the duration of an adolescent’s feelings of loneliness correlates with their risk for depression, even years down the line.

Many teens, such as Arreola, have also taken on new responsibilities, which makes them less available to their friends — and their inaccessibility can be misinterpreted. “My friends, we would go out constantly, just to be around each other. And right now, it feels like I’ve distanced so much from everybody,” Arreola says. “It’s just harder to keep in touch.”

Even when teens do have down time, they don’t always realize how much more intentional and proactive they have to be to maintain their friendships. “You have to make a lot more of an effort,” Ballman says. “I’ve been doing my best to keep up with my friends as much as possible, but it’s a lot harder than I realized.”

Research suggests that relationships between teens and their parents have grown more strained during the pandemic, too. In a study published in December, researchers at the CDC reported that although overall emergency room visits due to child abuse or neglect went down during the pandemic compared with 2019 numbers, the proportion of visits that required hospitalization increased — which suggests that fewer families sought medical care for minor injuries stemming from domestic violence and neglect.

And even when teens and their parents get along, things aren’t always easy. Many teens, including Arreola, feel a deep responsibility to support and protect their parents. Early on in the pandemic, Lara, the California college freshman, took a job to support her parents and then quit because she worried that she might catch Covid-19 at work and bring it home. “I was very concerned for my family — I really wanted to help them with the mortgage and paying for taxes,” she says. But “knowing that the virus impacts older folks way more than it would affect me,” she adds, “I chose to quit.” Lara eventually got another job she could do from home, and she splits her income with her parents, but she says it is exhausting.

Teens also may not be getting the support they need from even the most well-meaning parents — and understandably so, as many adults are also struggling. One problem is that teens often do not know how to ask for help. “They’re feeling all the strain of the pandemic, but for one reason or another, it’s not a conversation they can have with their folks,” Damour says. Larsen, the English teacher, says that students often linger online after class to vent about their home life. One student cried and told her, “I can’t talk to anybody in my house.”

One important question is how teens are coping with all of these added stresses — and whether they might be engaging in more risky or unhealthy behaviors. It’s unclear as yet how the pandemic is shaping overall adolescent substance use, but when researchers surveyed Canadian adolescents in the summer of 2020 as part of a study that has not yet been peer-reviewed, they found rates higher than those reported before the pandemic; more than half said they had used substances — most commonly alcohol, nicotine, or cannabis — over the past 90 days, and nearly one in five said they were using them at least once a week.

It can be hard to tell the difference between normal feelings of sadness and dissatisfaction related to the pandemic and signs of clinical depression that might require professional help. But one warning sign is that people with depression often lose interest in the activities they used to enjoy. If you have a teen who “is withdrawing more and is not engaged or connected to their friends in any way, that would be a big red flag,” Gurwitch, the Duke psychologist, says. Other signs of clinical depression include eating or sleeping a lot more or less than usual. If you’re worried about a teen, reach out to a pediatrician, school counselor, or a local mental health organization, Gurwitch suggests.

Psychologists also recommend that parents try to connect with their teens and show them empathy. “Don’t stop asking, ‘How are you? How can I be helpful? You seem sad, you seem depressed, you seem frustrated, my door’s always open,’” says Silverman. “Even if it feels like it’s falling on deaf ears.” Importantly, she adds, parents also need to drop what they’re doing and engage with their kids when they do want to talk, even if it’s at an inconvenient time. “When you’re about to get on a work call, or at two o’clock in the morning, that may be exactly when they are ready to open up to you. And I usually say that the inconvenient call comes at the inconvenient time because cries for help don’t wait for a hole in your schedule,” Silverman says.

Damour agrees. “Kids do create openings, but we need to be attentive to those openings,” she says. And in those moments, it’s important to listen — to quietly be there for your teen and to resist trying to solve all their problems. “When kids come to us, they don’t often want us to make suggestions,” she says. “And that’s usually what we do.”

What parents should do with a struggling teen is acknowledge that this is a terrible time and that what is being asked of them is unfair, Damour suggests. Beyond that, it’s often most helpful to listen, or even to sit together in silence. “It can just be two people sitting with each other and feeling that sense of connection and maybe a little bit of normalcy,” Silverman says.

Fagell suggests also helping teens become more flexible and positive in how they interpret their friends’ behavior. An adolescent might assume that her best friend hasn’t texted her back yet because she’s angry, when it may just be that she’s busy. “Ask them to come up with five alternative explanations,” Fagell says. The alternatives don’t have to be realistic, and your child doesn’t have to believe them. “But I just want kids to get in the habit of thinking a bit more flexibly to help them have an easier time assuming positive intent, and to help them sit with the discomfort in those moments.”

Parents might also want to grant their teens more space, independence, and control. “If we can give our teens some sense of control during this pandemic, their outcomes are going to be much, much better than if we try to do everything for them or dictate how it’s going to be done,” Gurwitch says. “I think that’s incredibly important.”

Fagell agrees. “We want to always be helping kids not feel like victims of fate, but to feel like they’re in the driver’s seat, and there’s always something they can do to improve their circumstances,” she says. Help them recognize that even in difficult situations, they can still make choices that would make things easier. Parents might also want to ask if their teen is interested in doing more to support their family or community, Silverman says, because having a sense of purpose can boost their spirits as well. Perhaps they want to cook dinner once a week for the family or look for volunteer opportunities online.

Schools should be doing much more to reach out to students to offer counseling and support, too. “Having more therapists at school — I feel like they’d help so many kids,” Arreola says. Eugene Vang, a junior at the University of California, San Diego, agrees. “Sometimes we just need our school to tell us that they’re present,” he says. “And they’re going to be here for us.”

The pandemic is going to be a formative experience in adolescents’ lives. It will shape them forever, and many will bear the scars of its stress and pain for years. “There will be crisis, there will be loss, there will be trauma,” says David Schonfeld, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. But “there will also be many who end up taking this experience and changing in some way — becoming more resilient.” For some, the pain will sow seeds that will grow into greater strength and sense of perspective.

Arreola certainly feels that way. Her days are long and hard, but the pandemic has “made me appreciate everyone in my life,” she says. “Life is so short.”

If you or someone you know are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HELLO to 741741.

UPDATE: An earlier version of this article incorrectly described Eugene Vang as a freshman at the University of California, San Diego. He is a junior.

Melinda Wenner Moyer is a science journalist based in New York’s Hudson Valley. She is the author of the forthcoming book “How To Raise Kids Who Aren’t Assholes.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

“The pandemic” is not the cause of these young people’s distress. GOVERNMENT OVER-REACTION to the pandemic is the cause, in addition to mass media and social media fear-mongering. Government-ordered lockdowns and school closures caused this mental health crisis in young people. Not “Covid,” and not “the pandemic.”

Its interesting that so many youth spend a lot of time virtually, social media, gaming and not always in personal connections. But then because of the pandemic, being virtual is an issue. Hopefully this will make everyone realize that face to face communication is better than virtual and people will spend more time in real time with people.