Elizabeth Blackwell’s life has long figured prominently in the standard inspirational liturgy for little girls. In 1849, Blackwell became the first woman to graduate from an American medical school. She completed rigorous postgraduate training and led a busy professional life. She unlocked the doors of the male medical world and propped them wide open for the rest of us.

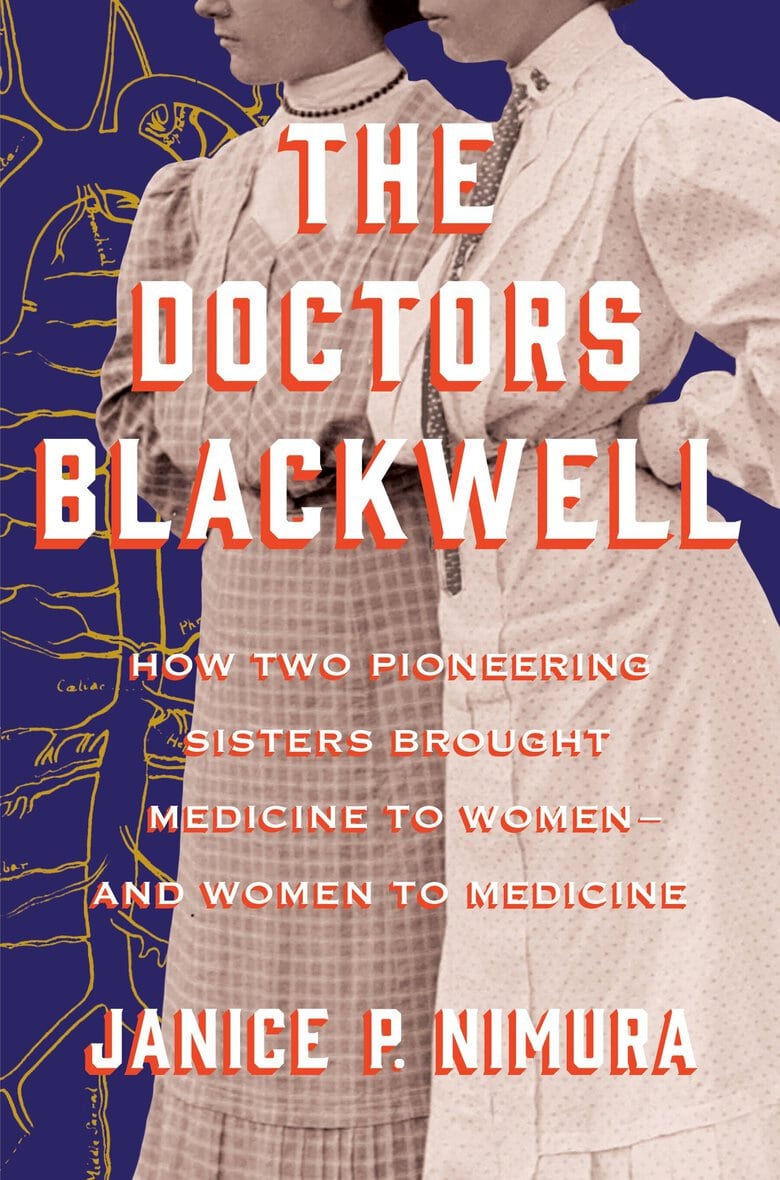

Needless to say, this hoary version of events contains some inaccuracies. For one thing, some doors barring women from male-dominated medical spheres are even now not yet open. For another, during much of recorded history uncredentialed women functioned as society’s primary healers. This truth strips any concept of “first doctor” of a certain amount of its sheen. And, most problematic of all, Blackwell was a real piece of work. As Janice P. Nimura makes clear in “The Doctors Blackwell,” her impeccably researched and beautifully articulated retelling, Blackwell was neither iconic feminist nor iconic physician, but both less and perhaps more of each than generally advertised.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Doctors Blackwell: How Two Pioneering Sisters Brought Medicine to Women — and Women to Medicine,” by Janice P. Nimura (W. W. Norton & Company, 336 pages).

The story’s arc is familiar enough. The first American female physician was actually not American at all. She emigrated from Britain in 1832, at age 11, with her large family of fervent abolitionists and religious dissenters. Although she spent time in the Midwest and practiced in New York City, Elizabeth always felt most at home in England, and would ultimately head back to retire there. Americans tended to find her stiff and standoffish in an off-putting British kind of a way. She, in turn, had fairly limited affection for those she once termed the “country boobies and boobyesses” of her adopted home.

The early death of Elizabeth’s father forced her to teach for a living, a job she loathed. The study of medicine appealed to her mostly for the “great moral struggle” of getting admitted. Was it the plaintive wish of a dying friend for a female physician that finally made Blackwell take the plunge? Nimura wonders about veracity of this story — Elizabeth was seldom quite so cuddly — and highlights instead Elizabeth’s grandiose notions that she was simply intended for great things: “I have a most perfect conviction, that holy influence surrounds me. I know that I am one of the Elect.”

Elizabeth was firmly rejected from every medical school she approached. Then the irresolute faculty of little Geneva Medical College in upstate New York turned the big decision over to its student body, and those boys knew an excellent joke when they saw one. They unanimously voted Elizabeth in. She had a predictably lonely time among them, and, also predictably, graduated at the top of the class. Then she worked at a mental hospital in Philadelphia and the great city obstetric hospital in Paris, gaining huge clinical experience in medicine, obstetrics, and surgery.

Ironically, it was a baby who casually unraveled most of her dreams — not her own baby, as she never married or had children, but somebody else’s. Tending to a Parisian newborn with congenital gonorrhea of the eyes, Elizabeth splashed infected fluid onto her face, infecting both of her eyes. The gruesome therapies of the day did little for her. Nine months later, her left eye was removed and Elizabeth’s surgical career, impossible with monocular vision, was over before it began.

Back in New York, she established an office practice that went nowhere despite (or perhaps because of) her notoriety. But she delivered well-received lectures on health and hygiene, acquired some powerful supporters among the municipal elite, and joined forces with two other women who were soon to become medical school graduates themselves. One was a Polish emigree, Marie Zakrzewska, who proved to be a workhorse clinician and, unlike Elizabeth, loved medical work for its own sake. The other was Elizabeth’s younger sister Emily, also far more of a clinician. These three founded and staffed first a clinic for women, then a women’s hospital, and, finally, a uniquely rigorous women’s medical school. The last was the acme of Elizabeth’s trajectory. Soon after it opened in 1869, she returned to Britain and accomplished no more. She died in Britain in 1910, at almost 90 years old.

From this familiar outline, Nimura, a scholar whose academic credentials are in East Asian studies but whose interests have long encompassed women and medicine, spins out some fascinating threads.

First is Elizabeth’s prickly, iconoclastic personality. It is amusing to consider what a modern admissions committee might have made of her. “Tell us about your interests, Miss Blackwell,” they might have asked, only to hear, as she wrote in her memoirs, “My favorite studies were history and metaphysics, and the very thought of dwelling on the physical structure of the body and its various ailments filled me with disgust.”

Second, Elizabeth’s great moral crusade actually did not open many doors, at least not immediately. Her alma mater in Geneva declined to admit Emily when she applied three years after Elizabeth graduated. Instead, Emily talked herself into Rush Medical College in Chicago, but when she suddenly found herself expelled from Rush after a year (the faculty changed its mind) she had to persuade a dean in Cleveland to let her finish and graduate. A few women’s medical colleges did open during these years, but they were not in any way a legacy of Elizabeth’s, or at least not one she would have accepted. She bitterly deplored their weak curricula and lack of rigor.

Elizabeth also was no feminist, at least not in any common sense of the word. The Blackwell family certainly supported women’s rights. One brother married Lucy Stone, the renowned suffragist, and another married Antoinette Brown, the first American woman ordained a minister. Elizabeth tolerated her sisters-in-law, but she wanted nothing to do with their crusade. She found most women intellectually inferior to men and worth no one’s trouble: “The petty, trifling, priest-ridden, gossiping, stupid, inane, women of our day — what can we do with them?” As Nimura points out, it might easily have been a paternalistic man writing.

From this profound contempt came Elizabeth’s self-assigned mission: to raise up the boobyesses and mold them in her own image of exalted, worthwhile humans. She delivered remarkably retro speeches: “The grandest name of woman is mother — the noblest through of womanhood is maternity.” Or was she simply blandly, cleverly mouthing familiar words to secure donations for her cause, as Nimura wonders? Was she acknowledging biology yet still demanding utter equality — a legitimate form of feminism? One never really knew with Elizabeth, and perhaps she never really knew with herself.

Her feelings about medicine were similarly muddled. It was always the right to practice the profession, rather than work itself, that appealed to her. She scorned 19th-century medical cults — Mesmerism, eclecticism, and the like — for their silliness. Yet regular 19th-century medical practice could horrify her too, with its violent purgatives and useless pseudoscientific routines. Her obsessions with preventive medicine and hygiene were prescient. Her obsessions with sexual prudence and moral rectitude, both of which she deemed essential for good health, were antique. She was an anti-vaxxer. She was all tangled up in theory and practice, good instincts, wishful thinking, and her own tactless, ambitious, narcissistic self.

Emily, by contrast, was simply a good doctor and a good soul. She had loved biology and the natural world from girlhood and gobbled up her medical studies. She became a skilled surgeon, and frequently served as intermediary between her difficult sister and the rest of the world. But Emily’s story is less interesting than Elizabeth’s.

Perhaps Elizabeth should be dethroned as the patron saint of medical women (Emily will do for that role) and anointed instead as the saint of another medical archetype: the ambivalent, conflicted, well-meaning doctor who chooses the profession for all the wrong reasons, and then somehow manages to stick it out, doing some little good in the process. We have more of these doctors than anyone might believe, and they will certainly recognize one of their own in Nimura’s elegant and perceptive book.

Abigail Zuger is a physician in New York City and a longtime contributor to The New York Times.