Materials science is the viola of scientific fields. Caught between two celebrated string instruments — the violin and the cello — the viola is often overlooked despite its essential role in a musical performance.

Similarly, materials science often pales next to physics and chemistry and the wondrous discoveries made in their name. In fact, few non-scientists even know what materials science is, let alone the contributions the field has made in shaping the human experience.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another” by Ainissa Ramirez (MIT Press, 328 pages).

In the beautifully written and thought-provoking book “The Alchemy of Us: How Humans and Matter Transformed One Another,” Ainissa Ramirez, a materials scientist and science writer, offers a paean to her field by scrutinizing eight different inventions and the role each played in transforming the modern world.

As Ramirez describes in the introduction, it was a humbling experience one night in a glassblowing class that inspired her to write the book. A few moments’ distraction while shaping a piece of glass into a vase caused her to lose control, and the molten cylinder fell to the ground, causing momentary panic and mayhem.

Not only did the incident give Ramirez a deeper respect for glass, and materials in general, but it brought her to the epiphany that drives the book: We invent and mold materials, and they in turn mold us.

Each of the book’s chapters focuses on a different invention, starting with clocks and ending with silicon chips. Along the way she investigates steel rails, telegraph wires, photographic materials, carbon filaments for light bulbs, hard disks, and scientific labware.

She pays pro forma tribute to famous inventors, of course. How could one write about the origins of artificial light and the telegraph without mentioning Thomas Edison and Samuel Morse?

But then Ramirez does something far more compelling: With each invention, she reaches deeper, for stories of the lesser-known figures behind the famous ones.

The chapter on photography, titled “Capture,” devotes several pages to Eadweard Muybridge, the photographer famous for his studies of motion, and nods at George Eastman of Eastman Kodak. But what Ramirez really wants to do is tell us of a little-known 19th-century inventor, Reverend Hannibal Goodwin of Newark, New Jersey, who invented a process for making thin and flexible photographic film. Father Goodwin filed for his patent two years before Eastman, and a patent fight between Goodwin and Eastman Kodak lasted for decades.

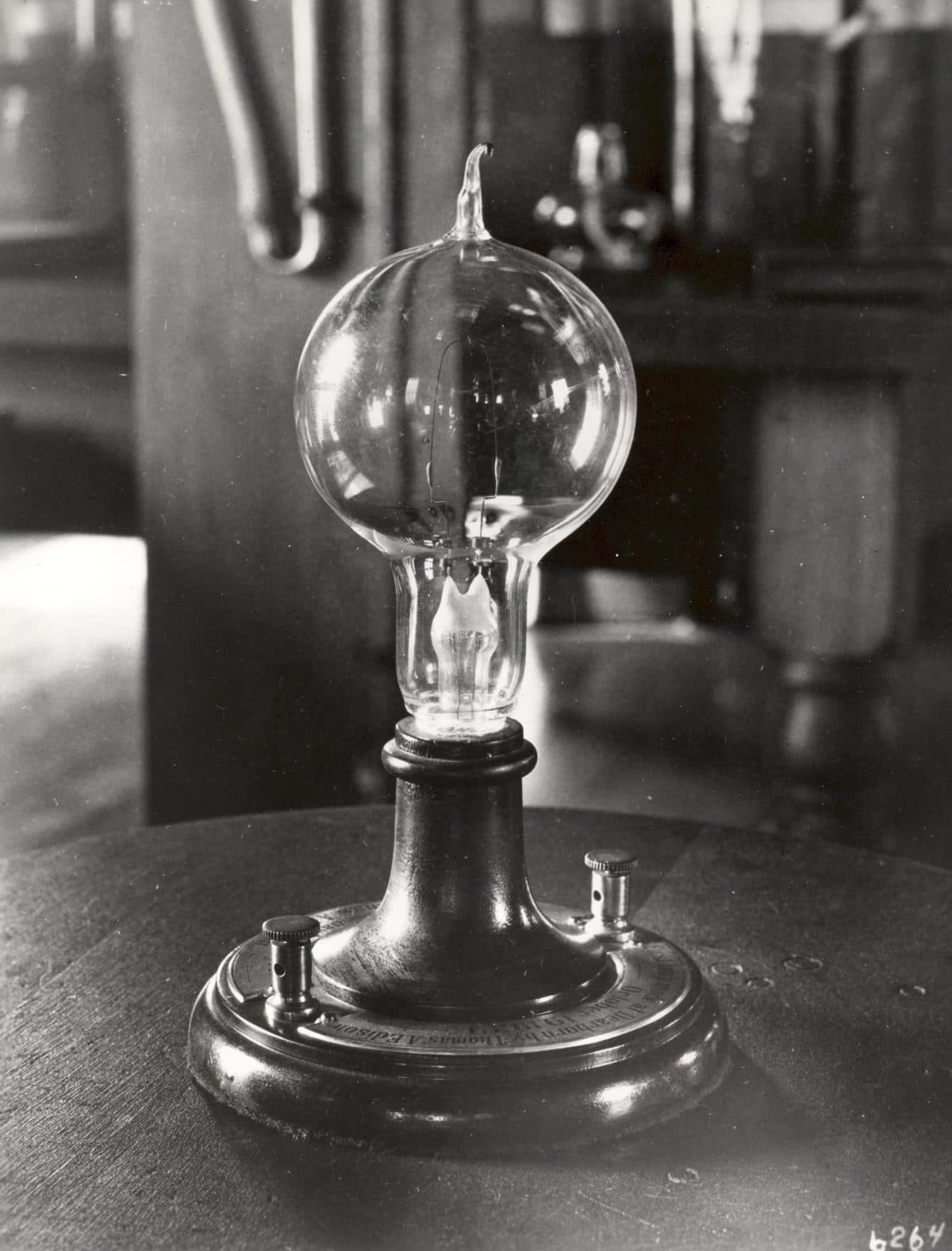

Ramirez’s reverence for the under-celebrated extends to William Wallace, who, filled with happy anticipation, showed Edison his “arc light” system. Edison rushed back to his own laboratory to create his famous electric light. “September 8, 1878, was supposed to be the best day of William Wallace’s life,” Ramirez writes. “Instead, it was the day that his own light went dark.”

An early light bulb created by Thomas Edison, the design of which was influenced by William Wallace.

Visual: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison Historical Park

Even more than a homage to the unsung heroes of invention, “The Alchemy of Us” provides a litany of unintended consequences wrought by the inventions it describes.

Who, for instance, would have associated the development of steel rails with the commercialization of Christmas? Indeed, when Christmas was transformed into a gift-giving occasion in the late 19th century in order to keep the economy going, the best way to move Christmas gifts — as well as trees and Christmas cards — was by rail.

Or the telegram’s influence on Ernest Hemingway’s writing style? Hemingway started out as a cub reporter at The Kansas City Star, which, like newspapers elsewhere at the time relied on the telegraph to receive reporters’ copy. Hemingway, writes Ramirez, loved the lean and unadorned prose required for telegraphic communication and embraced it as his own.

The chapter on clocks and the quest for ever more precise timekeeping starts with the story of Ruth Belville, the Greenwich Time Lady of England, who sold people the time by letting them look at her watch — which she set to Greenwich Mean Time — and adjust their own. From there, the chapter unfolds into a revelatory discussion of the effect of uniform timekeeping on our sleeping patterns, and the evolution from segmented sleep to consolidated sleep. “Our internal sleep clocks differ from the mechanical clocks we obey,” she writes.

Ramirez’s most powerful discussion of an invention’s effect on society comes in the chapter on photography. She points out that books about Polaroid tend to focus on the joy of instant photography without giving due to its social impact. In an early — and chilling — example of tech-enabled surveillance, Ramirez discusses at length the link between Polaroid and apartheid in South Africa.

In 1966, Polaroid created a system that produced two color photos in 60 seconds. This meant that one photo could be used for a personal ID and one for a government file. Four years later, two young Polaroid employees, Caroline Hunter and Ken Williams, discovered that the company was providing the means by which South Africa, a police state, controlled the motion of Black South Africans with a passbook system, with photos made by Polaroid.

Hunter and Williams formed the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement in 1970, organizing boycotts of Polaroid until it left South Africa. Hunter and Williams were promptly fired in 1971, but six years later, Polaroid finally stopped doing business in South Africa.

Just as interesting and impressive is Ramirez’s annotated bibliography, a rich guide to further reading. Ramirez is generous with giving credit to authors who preceded her. She doesn’t merely list Rebecca Solnit’s “River of Shadows,” about Eadweard Muybridge, but she calls it “transcendent,” a “literary masterpiece.”

And yet there is occasional carelessness. She misspells Walter Isaacson, the author of “The Innovators,” for one. And she confuses “affect” and “effect.” These and other mistakes could have been avoided with a better job of copy editing.

Nits aside, Ramirez is one of those rare science writers who can take her material, present it in wholly unexpected ways, and in the process reshape a reader’s fundamental understanding of a subject. Thank goodness she took that glassblowing class.

Katie Hafner is a journalist and the author of six works of nonfiction, including “Where Wizards Stayed up Late: The Origins of the Internet,” and most recently a memoir, “Mother Daughter Me.” She can be reached on Twitter at @KatieHafner.