One night in the summer of 1883, lightning struck a telephone wire on the campus of Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. Sparks flew into the nearby science building, which soon began to burn. As the fire spread, it made its way to the top-floor laboratory of ichthyologist David Starr Jordan, which was stocked with thousands of unique fish specimens, many still unnamed.

BOOK REVIEW — “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Story of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life,” by Lulu Miller (Simon & Schuster, 240 pages).

Jordan stored his fish in alcohol-filled jars, which would prove to be disastrous when the flames reached his lab. “The jars would have exploded like tiny bombs,” Lulu Miller writes in her unconventional new book about Jordan, “Why Fish Don’t Exist.” “Fish were vaporized. Unidentified creatures were incinerated, possibly never to be found again. Every last specimen was destroyed.”

It would be enough to break most people, but Jordan seemed to take the destruction of his life’s work in stride. “He dusted up the ashes, and headed right back out to the nation’s bodies of water to retrieve what he had lost,” Miller writes.

It’s this resilience, this “shield of optimism,” that drew Miller, a science journalist searching for meaning in her own life, to Jordan’s story. But Jordan’s doggedness had a dark side, too, Miller discovers. This discovery turns what initially seems like an homage to an indomitable scientist into a philosophical tale about the limitations of tidy narratives and the dangers of unyielding belief.

Jordan was born in Western New York in 1851, to a very Puritan family. His desire for order expressed itself early, and he spent his childhood making maps, memorizing the name of every star, and collecting wildflowers. Tragedy struck early, too; Jordan’s older brother Rufus, whom he adored, died when Jordan was 11. Trying to organize the natural world might have served as a “sweet salve” for his pain, Miller suggests.

In the summer of 1873, not long after graduating from Cornell University, Jordan took a tugboat to Penikese Island, a rocky outcrop off the coast of Massachusetts, to attend a summer school led by Louis Agassiz, a renowned naturalist and Harvard professor. Like Aristotle before him, Agassiz believed that every life form on the planet could be arranged into a hierarchy “of perfection,” with humans sitting comfortably at the top. To him, taxonomy was a divine endeavor. “Agassiz believed that by arranging these organisms into their proper order, one could come to discern not just the intent of a holy maker but perhaps even the instructions for how to become better,” Miller writes.

Agassiz’s views were a revelation to Jordan, giving him a powerful purpose and recasting his interest in collecting as “missionary work of the highest order,” Miller explains. Jordan, who had never seen the sea before, spent the summer learning from Agassiz and marveling at the strange creatures they pulled out of the ocean.

Jordan decided to devote his life to fish, becoming an ichthyologist who mounted collecting expeditions all over the country and, eventually, the world. He was a “fish addict,” an obsessive completionist who, Miller says, “set himself the goal of discovering every freshwater fish in North America.” And he very nearly did, reeling in new fish by the bucketful; on a single trip to the West Coast, Jordan and one of his students named more than 80 new fish species. Over the course of his career, Jordan and his team would eventually discover nearly one-fifth of the fish known to science at the time, bestowing them with scientific names and drawing new links between species.

Though Jordan ultimately rejected Agassiz’s belief in a holy creator in favor of Darwin’s theory of evolution, he pursued his work with the same kind of moral fervor. “By looking very closely at fish anatomy, he told himself, he was discovering our true creation story, what experiments in life it took to make humans,” Miller writes. “And he was uncovering the clues — written in the accidental missteps and successes of other creatures — that could potentially help our kind advance even further.”

Jordan went on to become the president of Indiana University and then the founding president of Stanford University, where he faced his second major scientific disaster. After the Indiana fire, he created an entirely new collection of fish, stacked in jars almost two stories high. Each jar contained a tin tag, which Jordan had stamped with the specimen’s brand-new scientific name.

In the early morning of April 18, 1906, an enormous earthquake, a 7.9 on the Richter scale, hit Northern California. Jordan, who’d been asleep at home, raced to his lab. He found it in shambles. “Fish were everywhere,” Miller writes. “Glass was strewn all over the floor. Flounders bashed further flat by fallen stone. Eels severed by shelves. Blowfish popped by shards of glass. There was a pungent smell of ethanol and corpse.”

“But far worse than any of the carnal damage was the existential,” she continues. “For many of those specimens left intact, hundreds of them, nearly a thousand, their holy name tags had scattered all over the laboratory floor. In those 47 seconds, Genesis had been reversed: His meticulously named fish had become an amorphous unknown again.”

Jordan sprang into action, enlisting two of his colleagues — Stanford professors — to stand in his lab with hoses, spraying water over the fish so they wouldn’t dry out. Meanwhile, Jordan grabbed a needle and thread and began picking out the specimens he recognized, stitching the tin name tags directly to the fish.

This single-minded tenacity seduced Miller and made her want to tell Jordan’s story. Even beyond his scientific setbacks, Jordan was a man intimately acquainted with loss, forced to contend with the untimely death not only of his older brother, but also his first wife, a close friend, two students, and two of his children. And yet, he always forged ahead.

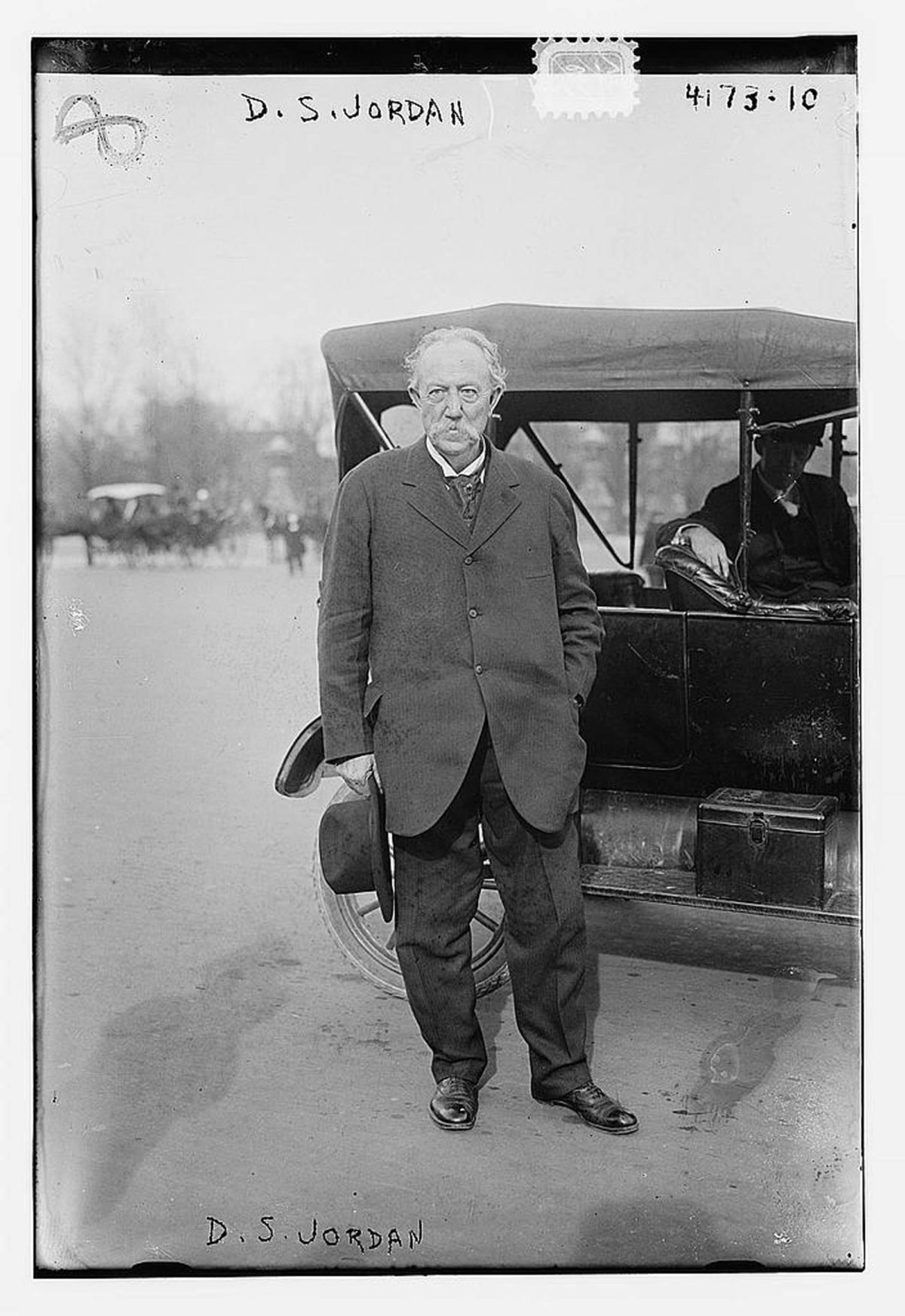

David Starr Jordan, photographed between ca. 1915 and ca. 1920.

Visual: The Library of Congress / flickr

To Miller — who had struggled with depression and whose biochemist father had taught her that individual human lives were, in the grand scheme of things, insignificant — it seemed like Jordan had deciphered some secret code. “I wondered what it was that allowed him to keep plunging his sewing needle at Chaos, in spite of all the clear warnings that he would never prevail,” Miller writes. “I wondered if he had stumbled across some trick, some prescription for hope in an uncaring world”

“Perhaps,” she continues, “he had cracked something essential about how to have hope in a world of no promises, about how to carry forward on the darkest days.”

But eventually Miller comes to question the man she once thought might help her navigate the turbulence of life. Jordan’s resolve, his unflagging belief in his work and the world as he saw it, led him to some truly ugly places. The corollary to Jordan’s belief that humans could improve themselves as a species was that certain “unfit” individuals could drag the entire species down. Jordan became one of America’s leading eugenicists, pursuing his agenda with his typical fervor, pushing for the forced sterilization of entire classes of people he viewed as unworthy.

“He wielded his belief in a natural order like a blade, convincing people that sterilization was the soundest way — the only way — of saving the human race,” Miller writes. He never abandoned or renounced these beliefs, even after the public, the legal system, and the scientific community eventually turned against them. “David held fast to this idea of a ladder,” Miller writes. “He clung to it, in the face of waves of counterevidence that should have eventually ended it.”

Miller is shaken to discover that she had been modeling herself “after a villain.” She, like Jordan, had craved certainty and purpose, some sense of a “natural order” that would imbue her life with meaning. But, as she eloquently argues, this kind of certitude, this insistence on order, this urge to simplify and categorize the world, is a trap. Ultimately, she finds a different way forward by doing something that her onetime hero never did — she allows herself to doubt.