A Popular Anti-Clotting Device May Do More Harm than Good

In 1992, Susan Stedronsky Karnstedt was living in Chicago and flying around the world for work. Upon her return from a particular trip, she recalled having pain in her leg. She’d initially assumed it was a pulled muscle, but it turned out to be a potentially dangerous blood clot in a vein near her pelvis, partly attributed to her relentless plane travel. At the hospital, the doctors placed a spindly metal contraption in the largest vein in the body, the vena cava, to catch the clot.

“There was no discussion about it,” Karnstedt recalled. “We knew at the time that it was a permanent device, but nobody talks about the long-term implications of having that device in your body for that period of time.”

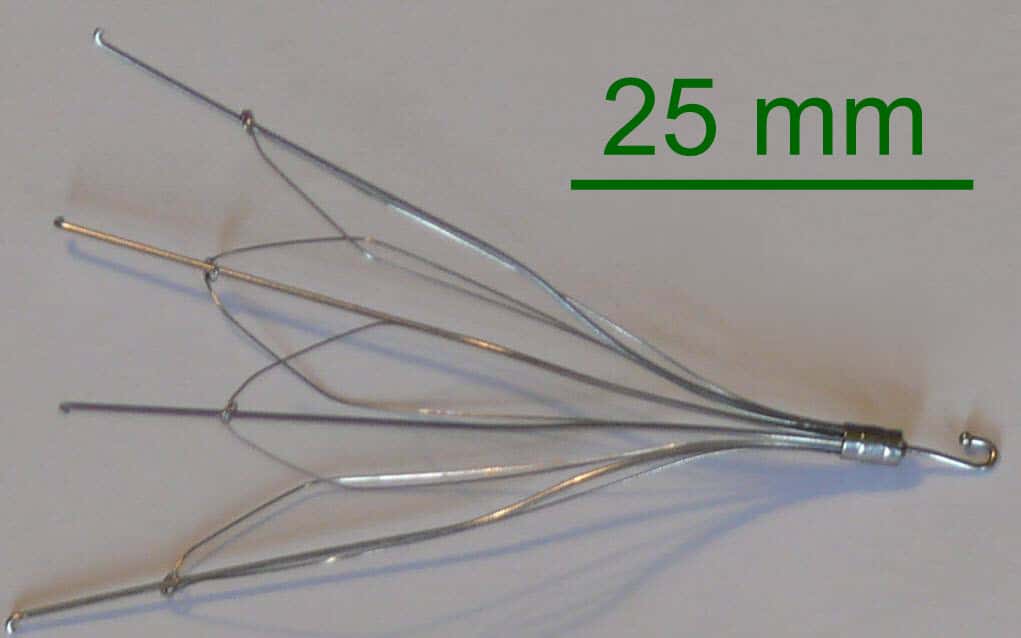

The device, an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter, is shaped like a badminton shuttlecock. The basket blocks blood clots from migrating through the bloodstream to the lungs, where they could cause a blockage — a condition called a pulmonary embolism. The development of a pulmonary embolism, if not caught or treated, can be life-threatening, and it is the third most common cause of cardiovascular death among Americans, just behind heart attack and stroke. Pulmonary embolisms are typically treated with blood thinners, or anticoagulants, but for some patients, such drugs can fail or prove hazardous, especially in people with a high risk of a bleed, or who have had recent major surgery.

That’s where IVC filters come in, and Karnstedt is in good company. Between 1982 and 2012, there was a 1,300-fold increase in IVC filters in the United States. The problem: The devices have long been dogged by controversy and reports of complications. Indeed, a paucity of robust medical evidence showing how well they actually work has led some doctors to begin advocating against them, and while use of the filters has declined in recent years, complications can occur even long after they’re put in place.

A decade after Karnstedt received her filter, she was experiencing abdominal issues. An MRI revealed that the device was perforating her small intestine, mere millimeters from her aorta. The discovery, she said, was horrifying. “I was envisioning, you know, driving,” she said, “and, like, stroking out and killing my family.” It’s a common story. According to DrugWatch, a consumer advocacy organization that provides information about medical device complications and connects consumers with lawyers, as of July 2019, more than 14,000 lawsuits had been filed against IVC filter manufacturers, suggesting the filters are linked to many other poor health outcomes.

Some doctors still argue the filters are useful, at least in some circumstances. “Are filters preferred compared to anticoagulation? Clearly no. Are they preferred to doing nothing? In my view, clearly yes,” Brian Funaki, a professor of radiology at University of Chicago, wrote in an email message. When used properly and for reasonable indications, the filters are effective and safe, Funaki argues, “but like any medical device, far from perfect — and we continue to learn when and when not to place them.”

But others in the medical community say the filters may be doing more harm than good, with some doctors calling for their removal from the market altogether — or at least until more studies have been done that show that they work. “The question is always: Is the person who gets a filter, on average, better off by having it? And the answer is, we don’t know,” said Vinay Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist at Oregon Health and Science University. “And that’s not a very comfortable thing to tell somebody who you just put a piece of metal in.”

A clot in the vein is called a venous thrombus, and there are two types: deep vein thrombosis, where a clot forms in a deep vein, usually the leg; and the less common and far more dangerous pulmonary embolism, which occurs when a clot, usually from deep vein thrombosis, breaks off and travels to the lung. Karnstedt’s clot was a type of deep vein thrombosis, and the filter was placed to stop the clot from escaping to her lungs, where it could have caused a blockage.

In 1967, to combat pulmonary embolism, Kazi Mobin-Uddin, a vascular surgeon at the University of Miami, presented his design of the first IVC filter. At the time, Newsweek magazine hailed the device as the “umbrella of life.”

Since then, very few studies have tested the efficacy of IVC filters. In particular, there are few randomized controlled trials, which are designed to minimize bias and are often considered the gold standard in medical research. The first such study, conducted in 1998, found that the filters reduced the risk of pulmonary embolism, though the study did not show that the filters increased survival. In fact, the filters were shown to increase the risk of deep vein thrombosis. Today, the study’s design is now also considered obsolete, as it tested permanent filters that are now rarely used.

In the early 2000s, manufacturers introduced retrievable IVC filters, and there was a surge in filter placement. In 1979, 2,000 U.S. patients had IVC filters; Between 2005 and 2014, more than 1.1 million were placed.

But the retrievable filters are often never removed after placement. Studies consistently show that less than half of all filters are removed, with one study reporting retrieval rates as low as 8.5 percent.

In 2010, the FDA issued a warning about the risks of IVC filters after receiving more than 900 reports of adverse events between 2005 and 2010. The report cautioned that there was a risk of filter fracture, device migration, and vein perforation, and advised that the devices be removed as soon as the risk of pulmonary embolism had passed. The FDA updated the warning in 2014, repeating this advice.

Several studies have shown that the longer the filter is left in, the greater the associated risk of malfunction. In a 2015 study of filters placed over the past 44 years, filters were reported to have penetrated the vein wall in 19 percent of the cases.

David Brown, a cardiologist at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, echoed these outcomes, noting he has seen cases where “an arm of the filter will break off and it’ll end up in the lung.”

In addition to the hazards from device failure, some research suggests the filters may increase the risk of death. A 2018 study from the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) Network Open looked at 30-day mortality rates in patients with venous thromboembolism and who had IVC filters placed because they couldn’t receive blood thinners. The study found that death rates were higher in patients with the filter than those without. A similar 2018 study published at JAMA Internal Medicine found that the levels of 30-day mortality were higher among seniors hospitalized for an acute pulmonary embolism who received an IVC filter than those who didn’t.

Behnood Bikdeli, a cardiologist at Columbia University and an author of the JAMA Internal Medicine study, said these results, coupled with the “trade-offs between potential benefits versus potential harms” led him to believe “the indiscriminate use of the device should be minimized.”

Guidelines from professional medical associations are mixed. Most controversial is the placement of IVC filters for patients who don’t currently have a venous thromboembolism but are considered high-risk. According to a 2009 report in the Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, these may represent more than half of all filter placements.

These preventative filters are often used on a patient for whom the “physician feels is so high risk [for a clot] that they need to go above and beyond,” said Adam Cifu, a professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, “even though that’s been shown not to be effective in the randomized trials we have.”

Those who have suffered complications from IVC filters have begun to take action. Patients are suing on the grounds that these companies knew the devices were prone to fracture and migration, but failed to warn the public and the medical community. Some cases that have gone to trial have resulted in million-dollar awards to plaintiffs. Others have led to settlements for which payment amounts are not disclosed. (Karnstedt’s case falls beyond the statute of limitations, so she’s unable to pursue legal action.)

In 2015, NBC News reported that a device from one of the largest manufacturers of IVC filters, C.R. Bard, was associated with 27 deaths and at least 300 other non-fatal problems since its introduction in 2002. The report suggested that, despite being aware of the cases of injury and death, Bard didn’t issue a recall and continued to sell the filter for nearly three years. In 2005, the company introduced a modified series of filters, but according to NBC, these failed to resolve the issues. Bard continued selling them until 2010.

In 2018, the company was ordered to pay $3.6 million to a woman who suffered complications from one of its filters. In two other trials, Bard prevailed, while another lawsuit against the company ended in a settlement last year.

In a statement sent by email to Undark, Sandra Moskowitz, a spokesperson for BD, which acquired Bard in 2017, said that the company strongly disagrees with the findings of the NBC investigation. “Stating that the company did not properly notify physicians about the risks and benefits of the device is absolutely false,” she wrote. “Any implantable medical device carries inherent risks, but also provides clinical benefits that outweigh those risks.”

Despite the limited evidence for their efficacy, use of IVC filters remains high in the U.S.; a 2016 study by Bikdeli’s team found that one in six Medicare beneficiaries with a pulmonary embolism received an IVC filter between 1999 and 2010.

Brown said a financial incentive can be partly to blame. “Everybody wins financially. The manufacturers get paid, the doctors get paid, the hospitals get paid. And so, it’s hard to find somebody that doesn’t benefit from just, what the heck, putting them in,” he said. “Except for the patient.”

The lack of data on the devices, Brown said, is the medical system’s “carte blanche to put in as many as they want.” Until there are more robust studies, Brown said doctors should “boycott putting in filters.” Until then, he said the IVC filter should be taken off the market.

On Facebook, patients who have been affected or suffered complications from IVC filters offer sympathy and advice in a private support group. Karnstedt is among them. While she was able to have her filter removed by a doctor at Stanford University, she said she still suffers from long-term consequences, including pre-cancerous polyps at the site where the filter perforated her intestine and, she said, “massive digestive issues.”

Patients in the Facebook group often seek filter removal and recommend doctors to one another. In cases when patients have been turned away by their doctors because removing the filter seems too risky, the group often points to another member named Osman Ahmed, an interventional radiologist at the University of Chicago. With time and practice, Ahmed has become an expert at removing the filters; by his estimate, he has removed hundreds.

This also means Ahmed sees first-hand the serious complications the filter can cause. While he said he loves what he does, he added that he gets upset and frustrated with the effects that these devices can have on patients’ health.

But Ahmed said he is optimistic about the future, pointing to newer, safer types of filters in development, including one designed to dissolve and disappear into the bloodstream. IVC filter use is also in decline, according to a study co-authored by Ahmed: Filter placement fell by almost 26 percent from 2010 to 2014, when the FDA released its warning.

Ahmed noted that recently, he and his colleagues “were joking that like, you know, are we going to see a day where there’ll never be an IVC filter ever placed or made or be around to remove?”

“I can foresee like 20 or 30 years from now,” he added, “looking back and saying, can you imagine that we used to place these devices in people?”

Grace Browne is a freelance science journalist based in London. Her work as appeared in New Scientist, BBC Future, and Hakai magazine, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Are you familiar with Disraeli-Twain Statistics?

This article is full of them addressing each would require picking nits. No one would disagree with advising against indiscriminate use.