In Germany, a Heated Debate Over Homeopathy

In 2016, Christian Lübbers met a sobbing 4-year-old girl at his private medical practice in the south of Germany. The ear, nose, and throat physician quickly identified the source of the girl’s problem: acute inflammation of the middle ear. Though the condition is common, this particular visit was unusual. “You have to imagine, the ear canal was basically completely blocked — pus is coming out,” says Lübbers, “and as I was extracting it, I saw that the goop contained more or less intact white pieces.” Some were still the size of about half a Tic Tac. Others had partially dissolved, melded with the pus. He remembers turning to the girl’s parents and asking, “Have you, by any chance, put globuli in the ear?”

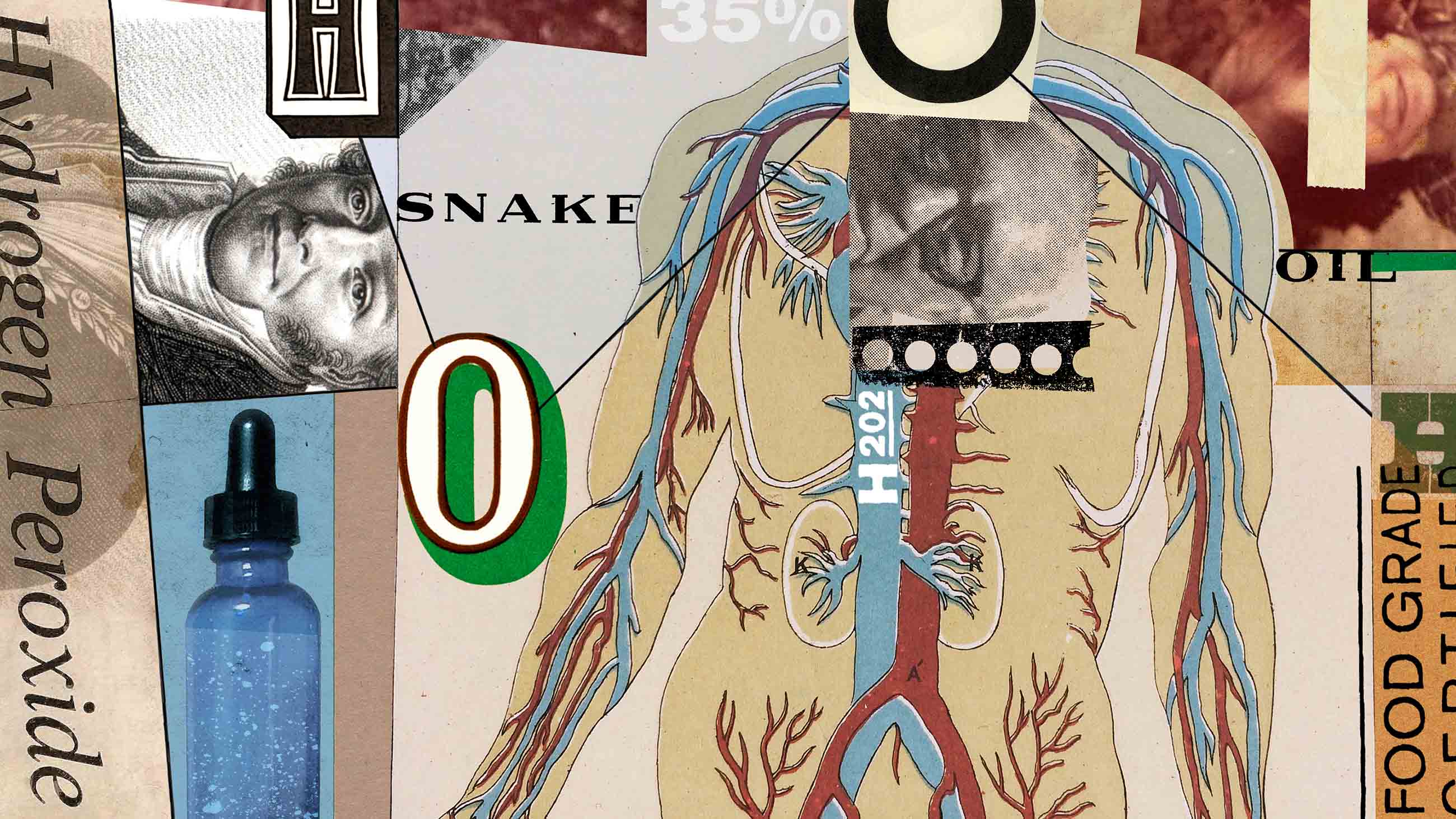

Globuli, the German term for tiny white balls comprised of sugar, are the main vehicle for administering homeopathy, a more than 200-year-old practice originally developed by a German physician named Samuel Hahnemann. In his day, Hahnemann experimented with a wide variety of substances that cause illness or symptoms in a healthy person. He believed that these substances — when given to a sick person — could cure the illness or lessen the symptoms that they would otherwise cause in a healthy person. Crucially, most of the time homeopathic products contain no traceable elements of the original substance. Instead, that original substance is diluted with water or alcohol. Practitioners claim that the substance’s “spirit-like power” is stored in water’s “memory.”

Homeopathy became wildly popular during the 19th century. The practice offered an alternative to mainstream medicine, which at the time, included ineffective and harmful treatments, such as bloodletting. Of course, over the past two centuries, the fields of medicine and public health have advanced dramatically. Vaccines, antibiotics, anesthesia, and a host of other interventions have all been rigorously tested and proven to be effective at saving lives and lengthening lifespans. Homeopathy, however, has not developed along similar lines. After a systematic review of 176 individual studies, Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council found that not a single high-quality study “reported either that homeopathy caused greater health improvements than placebo, or caused health improvements equal to those of another treatment.”

And yet reliance upon homeopathy is common, particularly in Europe. In Hahnemann’s native Germany, homeopathic treatments are prescribed by medical doctors, covered by 70 percent of government medical plans, and available in almost every pharmacy. In a 2014 survey, 60 percent of Germans reported trying homeopathy. The country’s homeopathic drug market is worth around $750 million (670 million euros), with consumers paying largely out of pocket. Consultation fees account for hundreds of millions more.

The practice is now at the center of a bitter political discussion, with some legislators, insurers and doctors saying homeopathy should not be included in the public insurance programs that cover most European citizens. In France, the health minister recently announced that she would phase out insurance reimbursement by 2021, following a review of more than 1,000 scientific studies that found no evidence for homeopathy’s effectiveness. In 2018, Austria’s Medical University of Vienna stopped teaching homeopathy to medical students.

But Germany appears likely to continue to support it — in a move that critics say could cause real harm to unwitting patients who forgo other treatments, believing homeopathy will cure them. Not only that, critics say, when homeopathy is covered by insurance, it’s a waste of the contributions the public is mandated to pay. Though physicians and researchers readily admit that homeopathy can yield some benefits by leveraging placebo effects, as well as practitioners’ empathy and listening skills, it’s a hefty sum for medications that have no active ingredients.

“In Germany,” Lübbers says, “we have a system in which we can register ‘sugar balls’ as medicine” and government insurance plans will pay for it. In his view, this represents nothing less than a national scandal.

After extracting the pus and globuli from the ear of his 4-year-old patient, Lübbers explained to the girl’s parents that the pills contain no active agent. At best, they work through a placebo effect, which can’t cure an infection. Upon hearing this, Lübbers says, the parents abandoned their belief in homeopathy and readily accepted his prescription for antibiotics.

Research suggests that the majority of patients are unaware that they’re being treated with sugar. In a 2009 survey in Germany, only 17 percent of respondents knew how homeopathic medicine was produced. The rest believed it to contain some sort of natural active agents. Lübbers says that he encounters this misconception in his office every day. “Roughly three-quarters of the people I tell that homeopathy isn’t natural medicine see their house of cards collapse; their support of homeopathy disintegrates,” he says.

For patients — especially those with undiagnosed diseases — this wrong belief can cause real harm. In Italy, a 7-year-old boy eventually died from encephalitis caused by a common ear infection. He had for a couple of weeks been treated with homeopathy, and, according to Italian media reports, his parents only called an ambulance when he lapsed into a semi-unconscious state. In Germany, a woman received homeopathic and other alternative treatments for her breast cancer for three years before consulting a medical doctor. The doctor confirmed the lump she had was malignant and recommended chemotherapy, but she continued with alternative treatments. The cancer eventually became fatal.

“If you receive these little balls directly from a globuli producer or from a witch, it doesn’t matter,” says Nikil Mukerji, a professor at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, who studies the philosophy of parascience. “You can even throw them over your right shoulder, but be careful,” Mukerji continues jokingly, “that it’s exactly five pieces and that they have the right spin.”

Mukerji says that many people turn to homeopathy after hearing that it “worked” for a friend or a family member. But, he says, it’s all too easy to assume correlation means causation. “If you’ve consulted a homeopath for a strong headache, then chances are — unrelated to what this person does with you — that your headache won’t be as strong the next day,” he says. In this kind of situation, it’s the passage of time that leads to physical improvement, not the sugar balls.

For some patients, the passage of time can exacerbate an underlying health problem. This was true for 4-year-old girl in Lübbers’ clinic. When she returned 2 days later, the antibiotics were working. The pus and tears were gone.

Lübbers has since gone on to become an outspoken homeopathy critic. He joined the Information Network Homeopathy, a loosely linked group of German experts hoping to educate the public about homeopathy, and has retold his story countless times on German radio, in newspapers, and on some of the country’s biggest talk shows. In November, when the government of Bavaria, the second-most populous German state, signed off on a $448,000 study to research whether homeopathy could reduce the use of antibiotics, he penned a scathing article in Zeit Online titled “Globukalypse now!” Since then, the study’s budget has doubled to nearly $900,000.

And yet, for all the passion on both sides of the issue, German Health Minister Jens Spahn said in September 2019 that that topic wasn’t worth fighting over, in part because insurers themselves spend relatively little — approximately $22 million a year — for homeopathic treatments. “I’ve decided on: It’s OK the way it is,” Spahn told reporters in 2019.

In an email to Undark, the health ministry added that it needed to accommodate “a large number of doctors and a wide group within the public who follow an ideological approach that is different from the scientifically-informed, conventional medicine” and act in line with German law.

That law has its roots in the 1950s, when a West German pharmaceutical company created thalidomide, a sedative that became popular among pregnant women because it reduced morning sickness. However, the drug had not been tested for its effects on embryonic development, and in 1960s, thalidomide was found to cause malformed limbs. Globally, over 10,000 children were affected. Ultimately, the German government went on to introduce a new law to regulate the pharmaceutical industry. Known as the Medicinal Products Act — the law stipulates that medicines need to be proven safe and effective before they are allowed on the market.

But lobbyists pushed to exempt homeopathy. Currently, the manufacturers of homeopathic medicine simply need to show that the ingredients in their products do not cause any direct harm. And if a company wants to market a homeopathic medicine for treatment of specific disease, it is sufficient for a group of homeopathic practitioners to attest to the products’ effectiveness based on a handful of case studies. The process is known as “internal consensus” and is one of the most ardently debated aspects of homeopathy.

So far, the German medical establishment has weighed in with mixed messages. In a joint communique from its 2018 federal meeting, the German Medical Association called on the government to reconsider privileges given to alternative medicine, criticizing the industry for operating without any evidence or standards. In the same communique, however, the association listed guidelines on how doctors could earn a professional distinction in homeopathy by training with homeopaths and taking an exam in front of other homeopathic practitioners.

“That’s like saying that unicorn riding is now going to be offered as a special professional distinction, with exams administered by unicorn-riding doctors,” quips Natalie Grams, a physician and head of Information Network Homeopathy.

Grams knows what she’s talking about. As one of roughly 7,000 German physicians also accredited in homeopathy, she used to spend weekends on professional development with other homeopathic practitioners. “Everything was awesome. The patients were satisfied and so was I,” she recalls. As criticism of homeopathy grew, she began writing a book that would present all of the evidence in support of homeopathy. The issue: She found none. In hindsight, she attributes her patients’ improvement to the placebo effect and the benefits of having a caring, unhurried practitioner.

With initial consultation fees of around $220, Grams was able to speak to her patients at length, sometimes for three hours or more. In contrast, doctors like Lübbers deplore the ever more efficient, tight schedule they are expected to follow in order to see all their patients. Primary care physicians in Germany spend, on average, just under eight minutes per patient, according to a systematic review published in the medical journal BMJ Open. In the United States, that figure is above 20 minutes.

Though homeopathic medicines are not as popular in the U.S. as they are in Europe, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that about 5 million adults and 1 million children used homeopathy in 2012. Even though the U.S. Food and Drug Administration attempts to better regulate the market, major retailers like Walmart, CVS, and Walgreens sell homeopathic products that resemble conventional flu and cold medicines and can be found in the same aisle. The Center for Inquiry, a science education nonprofit headquartered in Amherst, New York, has filed lawsuits against Walmart and CVS, accusing them of fraud for their sale and marketing of homeopathic products.

Matthew Burke, a neurologist at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center in Toronto, says the placebo effect could explain why many patients report improvement after taking homeopathic medicines or other products without active ingredients. In these cases, it’s not the medicine that stimulates healing, says Burke. Instead, improvements are driven by other factors, such as prior beliefs, or trust in one’s health care provider. And while some might place their trust in an Ivy League hospital, others might turn to vitamins from the Himalayas or homeopathic globuli.

Studies have shown that the placebo effect is more powerful than previously believed and that it can modulate certain areas of a patient’s brain, making it plausible that a placebo might relieve the symptoms of some conditions, says Burke. And beyond that, “The whole patient interaction — hearing somebody empathizing with them, developing a good therapeutic relationship, relieving some of their anxieties and worries, that’s really important and that’s something that unfortunately we don’t do as much as we should in medicine,” he says.

Both Lübbers and Grams agree that placebo effects are powerful and wish that medical doctors could spend more time with each patient. “As good as our medicine is scientifically,” Lübbers says, mainstream medicine has “completely ignored” the importance of spending clinic time with patients. But, he adds, for no other issue are the facts as crystal clear: Aside from the placebo effect, homeopathic medicines don’t work.

“If we don’t succeed in kicking homeopathy out of medicine and banning it to the kingdom of esoterica,” Lübbers asks, “then how can we even begin to talk about unnecessary back surgeries?”

As he leaves the clinic each day, Lübbers passes a glass cabinet that houses a collection of historic medical devices: pillboxes, a knife for bloodletting, and a mask onto which doctors dropped ether to anaesthetize patients.

Perhaps, someday, Lübbers will be able to lock globuli behind that door, too.

Denise Hruby is a bilingual reporter and editor who covers the climate crisis and environmental crime, politics, and social and human rights issues. Her reporting has appeared in National Geographic, CNN, The Washington Post, The Guardian, the LA Times, Nature, and the BBC.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It always works for me. I was an early case of covid. I got it just before it broke the news. Very very very sick for 6 weeks before I remembered the flu remedy in my drawer. One night of self dosing and the next day I was well. Still weak from the experience but I followed up with energy work and got through the next 3 years of pandemic just fine. Then last week I got sick again. My partner tested covid. I didn’t have to test . I knew the symptoms. I went straight to my remedies. 3 days later, a bit weak, but better. During the Spanish flu those who used homeopathy died far less and got better faster. There are records of these facts. I never heard of putting the gobules in ears. That sounds like someone without training did that. I self-learn for my own benefit only. It has helped me a lot, more than pharma. Everyone has the right to take care of their own body they way they want. I was constantly sick for 2 decades and constantly at mainstream doctors who always made me worse. Finally I quit mainstream and started to learn about safer and more effective alternatives and started to get better. A lot of people have had same experience as me. I’ve been to mainstream medical conferences where doctors are desperate and in anguish because they know the medicine they were taught is not very good. Corporate medicine is based largely on chemistry. Homeopathy is more physics. Future medicine will be physics and energy.

Homeopathy don’t argument. depend on natural treatment, beautiful result and helpful solution. Because argument is not a solution. Every Country even in Bangladesh 50% peoples used Homeopathy in 2021 century. Most of company investors they trying to stop the treatment. Honestly Hahnemann was an Allopathy physician when he fed-up then he convert. 21 century digital, if search on google we can easily reach everywhere. search the patients success case study with medical reports on homeopathy.

MUST READ

My husband was diagnosed with MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS five years ago. It’s very difficult for me to get him on board with major changes to his diet. We eat organic, non-GMO at home but his mom constantly gives us donuts, bagels, etc. I feel so lucky and happy i found World Herbs clinic on the internet. My husband only used their MS HERBAL FORMULA for three months and He was fully recovered. I believe this will be of great help to all MS patients across the world.

A new low level of paid journalism. No Homeopath advises to put a globuli into the ear. Thats not homeopathy. If someone has actually advised so, then it is the mistake of that individual. Havent you come across botched surgeries, wrong diagnosis in allopathic practise, and who is to be blamed for that? that particular doctor or the system he practices. Writing with ulterior motives will not take you anywhere….

Cardiac disease in bradycardia

No science was ever invented by one individual. No science is dogmatic or believes in some mysterious powers.

Let’s be real: Homöopathie is quackery. Through and through.

Homeopathy starts when all other pathies get failed.

No it is not advise by any qualified homoeopath

Shameful that half the people who are posting here have South Asian sounding names, and do not even know that homeopathy is not Indian in origin. I bet they don’t know that the key principle of Homeopathy is that “water has memory” or some such BS.

And, where there *may be* useful knowledge on new therapeutic compounds in plants or trees, classifying something like Ayurveda with nonsense like Homeopathy risks that the baby will be thrown out with the bathroom.

Came here to read about German/European treatment of nonsense, but couldn’t help but leave this comment.

*bathwater, not bathroom.

Also, these men should be shown

https://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2002/homeopathy.shtml

In the universe Homoeopathy is new scientific Modern system of Medicine, based on Natural Law. The need of the hour is genuine Research to find out the material or power in the Medicated Globules.

Do any studies with group of Homeo physicians, in consultation with conventional physician in any Acute, or Chronic condition.

The physician high and only mission is to restore the sick to Health, unfortunately so called physicians are more depending on Lab reports rather then ailing Human being

Treatment consists of 3 things

1.Emergency. 2.Surgical. 3.Medical

Homeopathy excels In Medical treatment

Homeo though uses Placebo, but it acts through its own power.

Since Time Immemorial Homeopathy,Ayurveda were practiced to cure/check various diseases both endemic and pandemic. While Allopathy never recognises Ayurveda and Homeopaqthy,it should be remembered that Homeopathy is widely used in Germany,Norway,Denmark etc. I lived in Denmark. Some Danish people used to ask me to get Publications on Homeopathy and Ayurveda from India as they are relatively cheap.

It is faith that is essential while using Ayurveda and Homeopathy Medicines. Is not Jaundice cured by traditional methods through medicinal leaves. My Brother treated over 15000 People for Jaundice,snakebite/scorpionbite etc without charging even a single rupee. He gives dosage after getting lab test results on Jaundice occurrence. So more scientific.

After Independence had Ayurveda and Homeopathy were given top preference, we might have become world leaders. Ayurveda and Homeopathy7 are affordable and as such many opt for it in Villages.

Dr.A.Jagadeesh Nellore(AP),India

Hats off Sir.

He did not disallow you to wash your mouth or rinse with water a few minutes after that, did he? So flimsy a ground to dishonor a system! Everyday thousnads of people across world die from side effects of allopathic medicines, many of them prescribed without any valid ground.

I am practicing homeopathy in India for last 32 years and never seen less than 100 patients a day (no elaborate paperwork needed here for insurance). During my days as a government doc I even attended 300 patients a day (don’t faint). Many of them of minor illnesses, but many would certainly haver eceived antibiotics and other ‘life saving’ drugs if they attended any allopathic clinic anywhere in the world. Fad of and sceptical myself that we’re curing only by placebo effects and our long and compassionate conversation with patients, I took it from the beginning to work the opposite way.Skill to diagnose quickly came from my allopathic teachers, huge patient load, and working in rural areas with no scope of lab investigation. Now I am practicing in urban area, cater more patients than most of allopathic MDs and write far fewer lab tests. Need to refer only few patients for allopathic care. And I am satisfied to my core that it is not the compassionate talks or placebo effect that bring more than 100 people a day to my clinic. Not that I have not used allopathic medicine for myself or my family ever, but those occasions are only a few till date, because every system had its limitation. But why should we be fanatic to discard the obvious? Only for money? Or loosing our money and common sense in the face of constant miligning by some people with vested interest? Many allopathic doctors also consults me or refer patients to me, I salute them for their open mindedness.

Hats off to you Sir, finally result matters most

The Australian government issued a “report” on homeopathy that asserted that there was no evidence that homeopathic medicines were effective for any condition. However, recent evidence has uncovered the fact that the first draft of this report by a respected group of researchers found some high-quality research showing evidence for homeopathy, but this initial report was rejected by government’s committee which was led by a known skeptic of homeopathy. Then, a new report by a different group of researchers was created with a highly biased anti-homeopathy evaluation. The Chairperson was asked to resign because he lied to the government by not acknowledging a serious conflict of interest he had in his opposition to homeopathy, but he still attended various hearings despite such actions being questionably ethical.

Even the highly prestigious Cochrane Commission in Australia acknowledged many studies published in leading conventional medical journals that showed benefits from homeopathic medicines.

Reference: Click here to access a thorough critique of this highly biased report on homeopathy.

https://www.hri-research.org/resources/homeopathy-the-debate/the-australian-report-on-homeopathy/

https://www.hri-research.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nhmrcdrafthomeopathyinformationpaper140408.pdf

Where exactly does this first draft show high quality evidence for efficacy or effectiveness of homeopathy? Do you all usually presume that someone won’t go have a look at the original draft? The conclusions are pretty clear. And where they say credible papers are not available, absence of evidence shouldn’t be taken as an evidence of anything (let alone homeopathy works). Please do use those high quality science papers to claim this US$ 1 million https://www.bbc.co.uk/science/horizon/2002/homeopathy.shtml

I have benefitted from homeopathy for my long standing throat problem. After an allopathic E&T specialist told me that allopathic treatment has ruined my throat by wrongly removing my tonsils. He advised me to try homeopathic treatment and it worked.

Western media has always done propoganda against homeopathic otherwise big allopathic companies will collapse. Homeopathy has cured many infections in me when allopathy failed…not one time, many many times and in my family also. Like I’m septic tonsillitis, jaundice, etc…the allopathic doctors (who were HOD of ENT, and Gastroenterologist) were really surprised and shock to find how homeopathy cured in extreme short duration of time.

It is very deep politics,,, about Homoeopathy,it is true that it proved on healthy human being,other pathy could not do so.If a medicine proved on lower classes animal,,(thing that) it effect on human body and cause physiological change but never determined in mental change.(In human patient) disease effect not only human body but also mind obviousl. So treat a patient completel, treat his/her mind equally,which never possible in other pathy except Homoeopathy.Because it remedy prepared after proved on healthy human being.

There is more recently in favor of homeopathy and I applause about the unexplained concept of Placebo effect. This would need special studies. Near Toulouse, in France, there is a Lab with a group of Engineers in Electronic working on something unexplained but really effective : “Bio-Photonic Bridges” applied on different schemes. The most successfull at the moment is on the topic of the Lyme desease. But other aspects need to be more studied, like the property of the water in 8 kHz excitation. In homeopaty, what is important is not the suggar or the dillution : this is the magnetic structure of the water mole. All living species are concerned in the field of investigation of the Biophotonic Bridges. Products from the bees can be tested in a mounting, showing their capacity to cure human beings. Item for acupuncture, homéopathy, Essential Oils, etc. The meaning of the recorded pictures on the screen should be discuss with experts, but why to bring new scientific elements to the discussion when the Regulatory Authority in Health domain is not ready to visit the labs and to allow some fundings for more information on the Life concept (plants, animals, human beings) ?

Well put. Time will undark.

Every morning I imbibe a potent homeopathic elixir. I drink a glass of New York City tap water.

No, it is NOT ANECDOTAL.

By the end of 2014, 189 randomised controlled trials of homeopathy on 100 different medical conditions had been published in peer-reviewed journals. Of these, 104 papers were placebo-controlled and were eligible for detailed review:

41% were positive (43 trials) – finding that homeopathy was effective

5% were negative (5 trials) – finding that homeopathy was ineffective

54% were inconclusive (56 trials)

How does this compare with evidence for conventional medicine?

An analysis of 1016 systematic reviews of RCTs of conventional medicine had strikingly similar findings:

44% were positive – the treatments were likely to be beneficial

7% were negative – the treatments were likely to be harmful

49% were inconclusive – the evidence did not support either benefit or harm.

Although the percentages of positive, negative and inconclusive results are similar in homeopathy and conventional medicine, it is important to recognise a vast difference in the quantity of research carried out; chart A represents 189 individual trials on homeopathy, whereas chart B represents 1016 reviews on conventional medicine, each analysing multiple trials.

This highlights the need for more research in homeopathy, particularly large-scale high quality repetitions of the most promising positive studies.

https://www.hri-research.org/…/there-is-no-scientific-evid…/

In the U.S., homeopathy advocacy can be more subtle. Consulting a specialist at the U of Md Baltimore about peripheral neuropathy, I was told she didn’t have any clues to its source, but some of her patients reported benefits from an OTC pill, which turns out to be a homeopathic “remedy”: box instructions: put a few (dextrose) pills under your tongue when you go to bed. Cavities, anyone? Where’s “First, do no harm”?

He did not disallow you to wash your mouth or rinse with water a few minutes after that, did he? So flimsy a ground to dishonor a system! Everyday thousnads of people across world die from side effects of allopathic medicines, many of them prescribed without any valid ground.

If homeopathic product labeling listed ingredient concentrations rather than dilutions the stupidity of these products would be explicit.

For example, “Arnica 0%”.

Even better would be a requirement that if the ingredient in question is undetectable, as above, then it could not be listed as transan ingredient at all.

An appropriate product label would transparently read, for example, “Contains water 100%”.

Such labeling would differ from current homeopathic labeling only in that it would not list how the 0% arnica or 100% water solutions were derived, i.e., their histories, but only what is actually in the container, what the consumer purchased.

This is a wonderful idea. If the FDA regulated these as foods or drugs, it could be required. Current policy, though, doesn’t seem to do so. Rather than the administration whose campaign was AMA-supported redefining NIH’s research on Complementary and Alternative Medicine as “Integrative Medicine,” regulating supplements and “remedies” this way would have benefited the public substantially. But I guess that would be anti-business and pro-Big Government.

All medicine has a placebo effect. However, since Homeopathic medicine demonstrates effect on plants, animals, babies, unconscious animals and humans and on humans utterly convinced it CANNOT work, then, pretty clearly, there is more than placebo at work.

Oh, I’d so much like to see the good-quality studies showing this. Sadly, there aren’t any, are there, Ms Ross?

Have you bothered to look or do you prefer to come from a place of prejudice and ignorance? There are not as many good quality studies because most research is funded by the pharmaceutical industry who has no interest. But yes, they are there. If your prejudice is too great to search through the Homeopathy Research Institute, then just work your way through NCBI. Pigs might fly I suspect. You know nothing but your own prejudice.

Quote: The following is an extract from an article entitled “Homeopathy In Influenza- A Chorus Of Fifty In Harmony” by W. A. Dewey, MD that appeared in the Journal of the American Institute of Homeopathy in 1920.

Dean W. A. Pearson of Philadelphia collected 26,795 cases of influenza treated by homeopathic physicians with a mortality of 1.05%, while the average old school mortality is 30%.

Thirty physicians in Connecticut responded to my request for data. They reported 6,602 cases with 55 deaths, which is less than 1%. In the transport service I had 81 cases on the way over. All recovered and were landed. Every man received homeopathic treatment. One ship lost 31 on the way. H. A. Roberts, MD, Derby, Connecticut.

In a plant of 8,000 workers we had only one death. The patients were not drugged to death. Gelsemium was practically the only remedy used. We used no aspirin and no vaccines. -Frank Wieland, MD, Chicago.

I did not lose a single case of influenza; my death rate in the pneumonias was 2.1%. The salycilates, including aspirin and quinine, were almost the sole standbys of the old school and it was a common thing to hear them speaking of losing 60% of their pneumonias.-Dudley A. Williams, MD, Providence, Rhode Island.

Clearly idiots for putting Homeopathic pillules in the ear. They are only ever taken dissolved under the tongue or dissolved in water before drinking. Sorry, but pillules in the ear is NOT homeopathic medicine.

And since Homeopathy has been healing and curing for more than two centuries, and has been practised for centuries by doctors also qualified in Allopathic medicine, pretty clearly, it works.

“healing and curing for more than two centuries”

And do you have any interobjective evidence for that statement? Because that is damm broad. Any homeopathy related cancer-curing, maybe?

Don’t ask for evidence from anyone promoting homeopathy. There is none, as she knows. It’s a con to extract all their money from vulnerable, desperate people.

There is a sort of evidence, as we all know. However, it’s anecdotal evidence. Because we are so easily convinced by a good story, and by firsthand and even secondhand personal testimony, it’s pretty potent. There’s also lots of it, whereas putting together controlled studies takes effort, expertise, funding, and the conviction that yet another study showing the these are placebo effects is more worth doing than other research that’s crying to be performed. Part of that calculus has to be the consideration of whether yet another “failure to show any advantage” is going to make a difference to people who are willing to try or recommend homeopathy.

The mere fact that Homeopathic medicine has survived and thrived for more than two centuries is not in the least damn broad.

Until the early 20th century when the pharmacists ganged up on Homeopathic medicine for intruding into its profits, there were Homeopathic hospitals throughout the US, UK, Europe and elsewhere. Homeopathy is still practised in those countries and continues to thrive with massive growth rates in India, China and South America. Why? Because it works and unlike allopathic medications does not kill people or cripple economies.

And given the huge failure rate of Allopathic medicine in curing Cancer you are being a tad hypocritical. You are also revealing you know zip about Homeopathy which treats the individual, not the disease. The body can cure anything in the right circumstances.

I am astonished at the blind prejudice by the Allopathic mafia against Homeopathy! I am a Homoeopathic physician with more than 30yrs of experience. I can say with pride that I have made some wonderful cures in my three decades of practice! I have successfully treated many cases of warts, kidney stones, menstrual problems, various kinds of allergies, enlarged glands, neuralgias and psychological problems. I studied Homoeopathy for the sheer love of the subject and I must confess that it has given me great satisfaction. I do not take fees. I charge only for medicine. I believe we can try curing COVID-19 with Homoeopathic medicine. The bias against Homoeopathy is condemnable! We should work in the interest of humanity! Money is not everything in life!

Here are few studies showing clinical results on the brain and other cancers. Dr Banerji is renowned for his method describe in his book :

https://www.amazon.com/Banerji-Protocols-Treatment-Homeopathic-Medicines/dp/938081321X

https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/26491/InTech-Homeopathy_treatment_of_cancer_with_the_banerji_protocols.pdf

https://www.spandidos-publications.com/or/20/1/69