In the Bombast of an American TV Host, Colonial Science Lives On

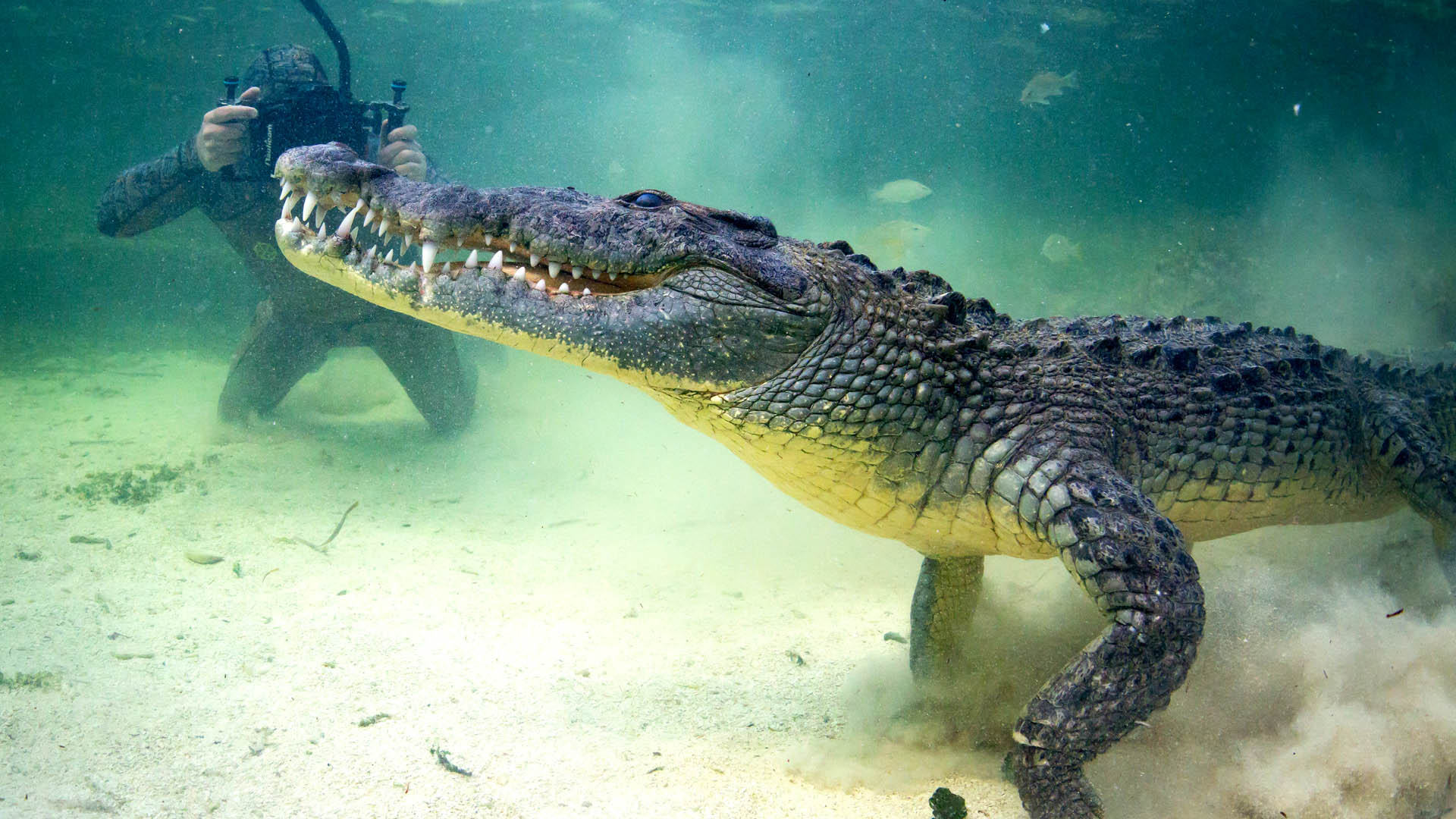

Sixty-five years ago in the Colombian jungle, a Latvian-born scientist named Fred Medem came across an unusual caiman, a smaller cousin to alligators and crocodiles. He was the first researcher to describe the creature, with its long snout and yellow hue, now known as Caiman crocodilus apaporiensis or the Rio Apaporis caiman. He believed it to be a subspecies of the more common spectacled caiman, evolving in isolation, separated from other caimans by a large waterfall and an 8-mile channel carved through a rocky gorge.

Skulls from Medem’s expedition made their way to the United States; the Cincinnati Zoo even hosted a live Rio Apaporis caiman until 1987. But in the following decades, the caiman’s forested, biodiverse habitat became impassable thanks to Colombia’s conflict between the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerillas, and the animal virtually vanished from the public consciousness and scientific circles.

But around a year ago and within months of each other, two young men came to the lagoons and riverbanks of this basin with the same goal: to re-discover the Rio Apaporis caiman. One was a Colombian biologist looking to document the genetics and appearance of this creature for science. The other was an American TV host whose show is aimed at re-discovering species once thought extinct, whose team had allegedly talked with the Colombian biologist about the caiman before either expedition departed.

In the first week of December 2019, the two announced separate but conflicting victories: The American, Forrest Galante, and his team released an episode of his show along with a press release stating he had discovered the Rio Apaporis caiman, while the Colombian scientist, Sergio Balaguera-Reina, published his findings in a major scientific journal.

Galante’s actions, which amounted to him claiming a discovery that had already been made a year before, are emblematic of a bigger, more common problem, said Markus Eichhorn, a forest ecologist at University College Cork who has studied exploitative practices in field ecology. And it’s not just a problem because a TV host failed to give credit where it’s due, Eichhorn added, but because it echoes a longstanding issue called “parachute science,” a colonial-style practice that sees scientific collaborators in developing countries as suppliers of data and specimens, rather than equals. And those local scientists are rarely mentioned in the big journals or media coverage.

Parachute science also happens in academic publishing, he said, but the stakes are rather different. “There’s a different dynamic when there is a media story involved.” While someone’s career may not be on the line, Eichorn added, “there is a big moral problem of who is getting the credit and the acclaim for something broadcast around the world.”

Balaguera-Reina grew up in central Colombia, By 2016, he had already authored a scientific paper in a major international journal and then earned a Ph.D. at Texas Tech University in 2018. Meanwhile, Galante is a made-for-TV biologist: Crocodile-Dundee-style hat and all. He has a biology degree from the University of California, Santa Barbara, but literature searches don’t turn him up as an author on any academic papers. (Galante declined to participate in an interview with Undark.)

So what was it that drew these seemingly very different men to this part of Colombia to look for this creature? In 2016, the Colombian government ratified a historic peace treaty with FARC that ended more than five decades of conflict. It was at that time that the international scientific community started to wonder: Was the Apaporis Caiman still there? And if so, was this strange, pointy caiman genetically distinct enough to really be a separate subspecies?

Also in 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the world’s authority on the conservation status of species, made the caiman mystery a priority, said Colette Adams, deputy director of the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Texas. Over the next two years, Adams worked with collaborators at CrocFest, a regular event founded and attended by conservation experts and reptile aficionados, that raises funds for specific crocodilian projects. The organizers were able to connect Balaguera-Reina with Texas reptile expert William Lamar, who, in the 1970s, was the last graduate student to study under Medem, the scientist who originally classified the caiman, and Lamar offered strong clues as to where to find the animal. Then, at the June 2018 CrocFest in Keenansville Florida, the organization raised $20,000 to support Balaguera-Reina on an expedition to Colombia, which he planned for December 2018.

But the buzz that CrocFest generated in the close-knit crocodilian community may have attracted Galante and his show, “Extinct or Alive” on Animal Planet. The show’s premise is that species can be mistakenly declared extinct, so Galante’s aim is to find creatures that, the show’s intro claims, “we have given up on.” While biodiversity field work is typically methodical and slow, Galante’s show edits the process down to exciting vignettes where he and his crew are the center of the action and local scientists are mostly behind the scenes. In just two seasons, Galante claims to have captured the presumed-extinct Zanzibar Leopard on film, and found the first Fernandina Island tortoise in the Galapagos Islands in over a century.

Even though Galante didn’t attend Crocfest, he and Balaguera were eventually put in touch by its organizers, which Balaguera-Reina said resulted in a November 2018 conference call with “Extinct or Alive” producers. Balaguera-Reina told Undark he gave the team all the information they needed to get to the likely habitat of the Rio Apaporis caiman and connected them with a guiding company that could help get them there.

According to Balaguera-Reina, Galante promised to help fund the Colombian scientist’s caiman research. “But I never saw any of it,” Balaguera-Reina said. Then Galante vanished off Balaguera-Reina’s radar.

The next month, Balaguera-Reina carried out his week-long expedition to the middle Apaporis River basin, where he documented 105 Rio Apaporis caimans across five survey areas. He also interviewed local indigenous people about their relationship to the creature and took genetic samples to clarify the genetic similarities between this population and the wider species. On the last day of his expedition, Balaguera-Reina posted photos of the rediscovered caiman as his success was celebrated by reptile enthusiasts all over the world.

Justin Miller, founding director of Pangolin Conservation and a zoo and conservationism insider remembered the photos circulating around the community. “There was a lot of excitement,” Miller said, primarily because of the fundraising buzz from Crocfest.

A year later, soon after his findings published in the Journal of Herpetology, Balaguera began to receive messages from friends and colleagues. But instead of just congratulations, the messages pointed him to a new episode of “Extinct or Alive,” featuring the Rio Apaporis caiman. In a teaser video posted online, Galante opens by pretending he’d been kidnapped by guerillas — and then admitting on camera that it was a joke — before announcing that he found the rare caiman. (Nearly 40,000 people were kidnapped in Colombia between 1970 and 2010). In another teaser, Galante cut tissue samples from a live caiman — though whether he had the permits to take and export the samples is unclear.

A press release posted on the Discovery Channel website also highlighted Galante’s claim that he had rediscovered an extinct creature. “The believed-extinct Rio Apaporis caiman (Caiman crocodilus apaporiensis) has been rediscovered by Forrest Galante, wildlife biologist and host of Animal Planet’s ‘Extinct or Alive,’ and team, making history once again,” it read.

“Thanks to genetic analysis,” the release also noted, “the species Galante discovered is entirely new!”

At the time, the press release didn’t mention Balaguera-Reina. But it did state that Galante’s team hired a private firm called Tangled Bank Conservation to do a genetic analysis and that their analysis confirmed that the creatures Galante and team saw are Rio Apaporis caiman. (JJ Apodaca, Tangled Bank’s lead scientist, confirmed to Undark that Forrest Galante and his team hired the firm for the genetic analysis of the Rio Apaporis caiman, but did not comment further.) The press release also said that Galante is working on a scientific paper that could allow the Rio Apaporis caiman to be classified as its own species, although, so far, it isn’t clear whether he has the scientific evidence to back up that claim.

The announcement of Galante’s claim caused a backlash online from those who had already seen Balaguera’s posts from a year before, said Miller. Many of the commenters didn’t directly call Galante out on the veracity of his claim, Miller added. But they would refer to Sergio’s work.

The Discovery Channel press release and Galante’s social media posts were hastily modified to acknowledge Balaguera-Reina’s paper and Galante obliquely addressed the matter on Joe Rogan’s popular podcast, saying the expeditions had been conducted “within a month” of each other.

While Galante declined an interview request from Undark, he did provide one written statement through a publicist. The statement read, in part, that any questions regarding the Rio Apaporis caiman are “best directed to Sergio and his team as he admittedly knows more than we do as the in-country scientist who is doing ongoing work on the species and in the area.”

“We are thrilled by Sergio’s discovery and work and wish him the best in the ongoing conservation of the species,” Galante continued. “We have done and will continue to funnel support towards his work in the hope that it contributes to the species’ ongoing survival.”

Galante’s statement did not specify the nature of that support, financial or otherwise.

Other researchers were unsurprised about Galante’s alleged activities in Colombia, including Washington Tapia-Aguilera, a biologist at the Galapagos Conservancy and director of the Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative. In February 2019, Tapia-Aguilera said, he had a similar experience when he accompanied a location shoot for “Extinct or Alive” in the Galapagos Islands.

On his website, Galante claims to have personally re-discovered the first example of a Fernandina giant tortoise in the Galapagos since it was last spotted in 1906. Numerous press outlets also attributed the discovery to Galante. But Tapia-Aguilera told Undark he, not Galante, actually decided where to look for the tortoise and Ecuadorian park ranger Jeffreys Málaga was the one that knew the land, tracked the tortoise, and ultimately made the discovery before calling over the rest of the team.

“Forrest and his team first are not scientists nor were they part of the scientific expedition,” Tapia-Aguilera said. “They were part of a television show.”

At the time, Tapia-Aguilera was surprised at Galante’s claim to have discovered the tortoise, but he was more focused on science and conservation outcomes: “I don’t care because I’m a scientist who does not seek prominence but instead to contribute to the conservation of giant tortoises, so recognition for me is not important.”

Both Balaguera-Reina and Tapia-Aguilera told Undark they thought Galante acted unethically, but saw him more as a TV host than a scientist. But the pattern is a larger problem in parts of the scientific community. Editorials in scientific journals, in international media and top scientists from major universities are increasingly highlighting the issue of parachute science, when a foreign scientist drops in, makes use of local infrastructure, talent, and resources, then returns to write a paper for a prestigious scientific journal. Although widely reported in relation to public health research in west Africa, the phenomenon has been little studied and hard numbers on its prevalence are hard to come by.

Parachute science “is incredibly damaging,“ wrote Asha de Vos, a Sri-Lankan marine biologist, by email. De Vos added that she has encountered the problem many times in her career and while running her research and education organization Oceanswell. “Because the expertise is imported and no investment is made in-country, these projects are not geared for long-term conservation efforts,” she wrote. “There is no sustainability to this model as a result.”

Eichhorn, the forest ecologist at University College Cork, recently co-authored a piece on decolonizing field ecology for major tropical ecology journal Biotropica. He told Undark that the practice was all too common and that although scientists in the developed world are increasingly aware of it, change has been slow. “I’ve been as guilty as anyone of glamorizing exotic field work, without properly acknowledging the impact of that and the inequality embedded in that,” he said, adding that the system has been built and maintained by academics in industrialized countries. They, in turn, decide where grants go and what — and who — gets published. “It’s this loop that makes it a hard nut to crack,” he said.

Eichhorn said that while it is damaging when scientists in the Global South are not being recognized or reaping rewards from their work, the greater damage is from a loss of global perspective. What questions, he wondered, aren’t scientists asking? What research isn’t being funded because of this model?

“We are just creating willing suppliers of more data instead of encouraging them to develop their own research programs and learning what research priorities fit their needs.”

Andrew J Wight is an Australian freelance science journalist based in Medellín, Colombia. He covers science in the Global South, in particular the role science plays in developing countries.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

As a wildlife biologist, I never assumed that any of the discoveries on Extinct or Alive were based on Galante’s original work. To even call it parachute science is generous in most cases. Someone with no training, degree, or experience in primatology who spends a week or 2 in the jungle looking for a primate that hasn’t been seen in a thousand years is not conducting serious science. I don’t know why the current entertainment trend is for these “adventurer” shows where the host pretends to know everything, and to have discovered everything; it’s rather insulting to the scientists who have spent their whole careers on this stuff, as well as misleading to the public regarding exactly how many resources and time usually need to go into these discoveries. Nevertheless, it is entertaining, good marketing for endangered species, and in the case of this show I comforted myself with the idea that based on their rhetoric, the show financially supported the local research. It’s disappointing to hear that may not be the case.

I also find this very one sided. I’m not a biologist but am a Chemical Engineer in my 25 yrs of working I have found that Scientists and Engineers are some of the worst offenders at taking credit from non scientists and engineers as well as each other. In my opinion, it should be like when someone murders somebody and another is there watching they are both as guilty regardless of their “titles” or how they both arrived at the scene. It should be the same here, not in the guilty sense of course, but in the achievement.

This article seems a bit one sided and seems to ignore other contributing factors. While Galante may have utilized anothers research in this one instance, isn’t it worth noting that he has had several other major findings with no controversy attached to them? Also he is not just another scientist but also a host of a show whos’ goal is to shine light on the existence of these critically endangered animals and in doing so procure additional funding for their conservation. Without people like Galante the general public would have no knowledge of this animal.

Sergio Balaguera-Reina was my PhD student and is already an amazing scientist (he has published some 40 papers). When he first told me about the interest that Galante had in the apaporis river caiman, I was very happy and assumed that they would go out to the locality together and that Sergio would get the credit for the discovery. Obviously that was not true. I want to thank Andrew Wright for doing this piece. However, do not worry this event will not impact Sergio’s career as he is already established as one of the best young crocodylian biologists in South America. However, it does reinforce the all too frequent observation that people that have little or no credibility, but do have connections can undermine the efforts of the folks that actually did the work.

It’s even worse than this. One doesn’t have to go abroad to find university scientists stealing the ideas and work of non-university scholars. I was part of a program in Minnesota, launched by local citizens, to involve the University in working on locally developed projects. There were some 15 of us; ranging from artisanal cheese to city lighting. At the big “sum up” meeting – we had a nice dinner- then a meeting just for the citizen scientists and 2 program execs. How did it go; ideas for doing better, that sort of thing.

Eventually – one citizen scientist broke down almost in tears and stated she’d been pushed out of her own work, ignored in its management, and left out of “next funding” directions… and left in no doubt she was an inferior intellect…

Then – it came out. 100% of us had exactly the same experience. Our research; our blood, sweat, and capital – had just been stolen. Every one. By 15 different sets of University professors.

Problem? Oh, yeah. From every possible aspect. The creative people not only get no rewards for their initiatives- but their creativity is then pushed aside from development, and good old standard processes replace innovation. And, oh, yeah; professors – with no ethics at all – get the rewards.

A quote from Galante on Balaguera-Reina:

A Colombian scientist named Sergio Balaguera-Reina has also discovered the caiman and published a paper on it this year. “The ongoing conservation work by an in-country scientist like Sergio is the best news of all,” Galante added.

It’s almost like you twisted the truth of the situation to fit the narrative you wanted to tell. Ironic, considering one of the taglines of this site is “Truth.”

Crap, should have read the rest of the article before posting.

Notably this statement was only put out after mass criticism in the herpetology community and only in one outlet- ignoring Balaguera-Reina both on the show and subsequent media pieces, but also-

“Also discovered the caiman” downplays that Galante used Balaguera-Reina’s instructions to find them. Maybe if he was unaware of Balaguera-Reina’s work you could argue that they were independent discoveries, but Galante is very clearly still attempting to falsely portray this as his own discovery.

Galante’s behaviour on social media further demonstrates he intends to claim full credit for this, only recognising Balaguera-Reina’s discovery after massive criticism, as a footnote, and blocking and deleting comments that mention Balaguera-Reina.

Great article! Thank you for addressing this. Many of us however, on social media, directly to Joe Rogans people and publicly in his comments, and on all the social media network promos very publicly denounced Forest Galante (tagging him until we were all blocked) and his stolen glory and falsified claims. We likened him to being no different than a comedian who steals other comics material, saying he ‘pulled a Mencia’ (getting the attention of JRE immediately) and coining new names like Forest Fraudlante as better suiting for this TV paper biologist. We’ve all maintained from the beginning that Sergio deserves every ounce of credit and Forest was nothing more than a trailing dingleberry that knew if they aired their episode fast enough that they’d beat the publication and could claim what they want. Thanks again for the great article and helping to expose him and these underlying issues.