Ben Carson, secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, made news earlier this year for his statements about transgender people.

In a September meeting with HUD staff, Carson remarked that he was concerned about “big, hairy men” trying to use women’s shelters. It is reported that his comments upset the HUD staff in attendance, causing one women to leave the room in protest.

Carson later doubled down on his comments in a congressional hearing, declining to apologize and saying “I think this whole concept of political correctness — you can say this, you can’t say that, you can’t repeat what someone said — is total foolishness.”

While his comments demonstrate a lack of understanding of the needs of transgender people, his agency’s moves to remove protections represent a real threat for transgender Americans who need shelter.

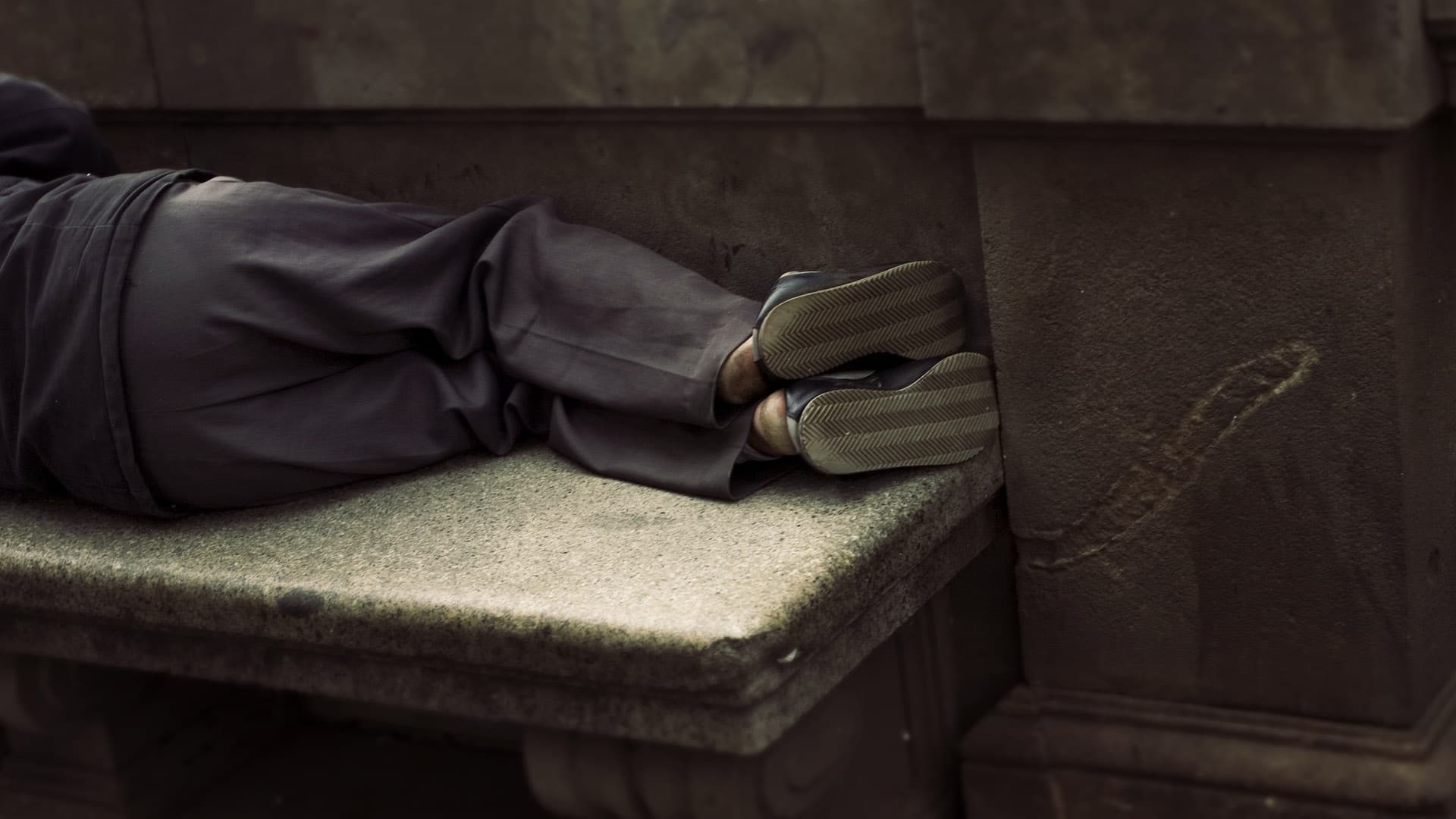

As my research shows, transgender people experience high rates of discrimination in housing and shelter services, exacerbating their already elevated rates of homelessness.

Discrimination and harassment in schools, at home, and in the workplace all contribute to high levels of poverty and homelessness among transgender Americans.

According to the 2017 U.S. Trans Survey, a survey of more than 27,000 transgender people across the U.S. conducted by the nonprofit National Center for Transgender Equality, 30 percent have experienced homelessness at some point in their lives. Twelve percent report at least one episode of homelessness in the last year.

Once they become homeless, transgender people are also likely to experience discrimination and harassment when seeking shelter services. A study by the Center for American Progress found that 21 percent of shelters refuse to serve transgender women.

While in a shelter, 70 percent of U.S. Trans Survey respondents reported harassment, sexual or physical assault due to their transgender identity.

This discrimination makes transgender people hesitant to seek shelter — more than a quarter of respondents reported avoiding staying in shelter due to fear or mistreatment.

There is a small but growing body of literature on the experiences and needs of transgender people living in homeless shelters.

Organizations that work on LGBTQ housing access, such as the National Center for Transgender Equality and True Colors United, recommend that shelters respect clients’ self-identified gender as best practice for housing transgender clients.

In practice, this can include housing clients in the dorm of their self-identified gender; offering private living and bathing spaces; training shelter staff about transgender identities; and adopting inclusive language in administrative paperwork, such as intake forms.

Recognizing both the high levels of need and the unique challenges faced by transgender people experiencing homelessness, the National Coalition for the Homeless adopted a nondiscrimination policy in 2003, which protects people on the basis of gender identity and expression.

In 2016, HUD implemented new regulations to protect transgender people from discrimination in housing services. The Gender Identity Rule clarified policies for single-gender shelter facilities with shared sleeping or living spaces.

It required all HUD funding recipients to respect the gender identity of transgender clients, housing them in facilities that align with their gender identity rather than their birth sex. It also removed a previous prohibition against asking about clients’ gender identity, allowing providers to ask about gender identity and house clients accordingly.

The rule included extensive guidance of how to safely house transgender clients, including information about bathroom facilities and how to deal with concerns or harassment from other clients.

While the Gender Identity Rule provided important protections, I also see significant weaknesses.

The nondiscrimination protections apply only to organizations which receive federal funding. Some shelters are run and funded by private, and often religious, organizations, and therefore do not have to follow this rule.

Enforcement mechanisms are also weak. Individuals who have experienced discrimination may submit a complaint to HUD’s Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity. However, people experiencing homelessness may not be aware of their rights or have the capacity to submit a complaint while struggling to meet their basic needs.

What’s more, the protections that this rule offers may soon be undone.

In May, HUD proposed a new rule that would give housing providers who get federal funding the right to establish their own policies regarding how to house transgender clients. The proposed rule states that organizations may use a client’s sex to make decisions about where and how to house them, without providing any guidance about how to determine an individual’s sex.

The proposed rule is now working its way through the regulatory process, with advocacy groups meeting with HUD to discuss its potential impact. It is also supposed to go through a period of public comment.

HUD has also scaled back enforcement of the Fair Housing Act, which protects against discrimination in housing based on race, religion, sex, ability, and other protected classes, by freezing investigations into discriminatory practices. This freeze includes investigations into discrimination against parolees and former inmates, people with disabilities, and racial or ethnic minorities.

The administration’s decision to halt these investigations implies that they do not consider nondiscrimination protections to be a priority. That can further endanger transgender people experiencing discrimination in shelters and housing services.

Jonah DeChants is a postdoctoral fellow in social work at Colorado State University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.