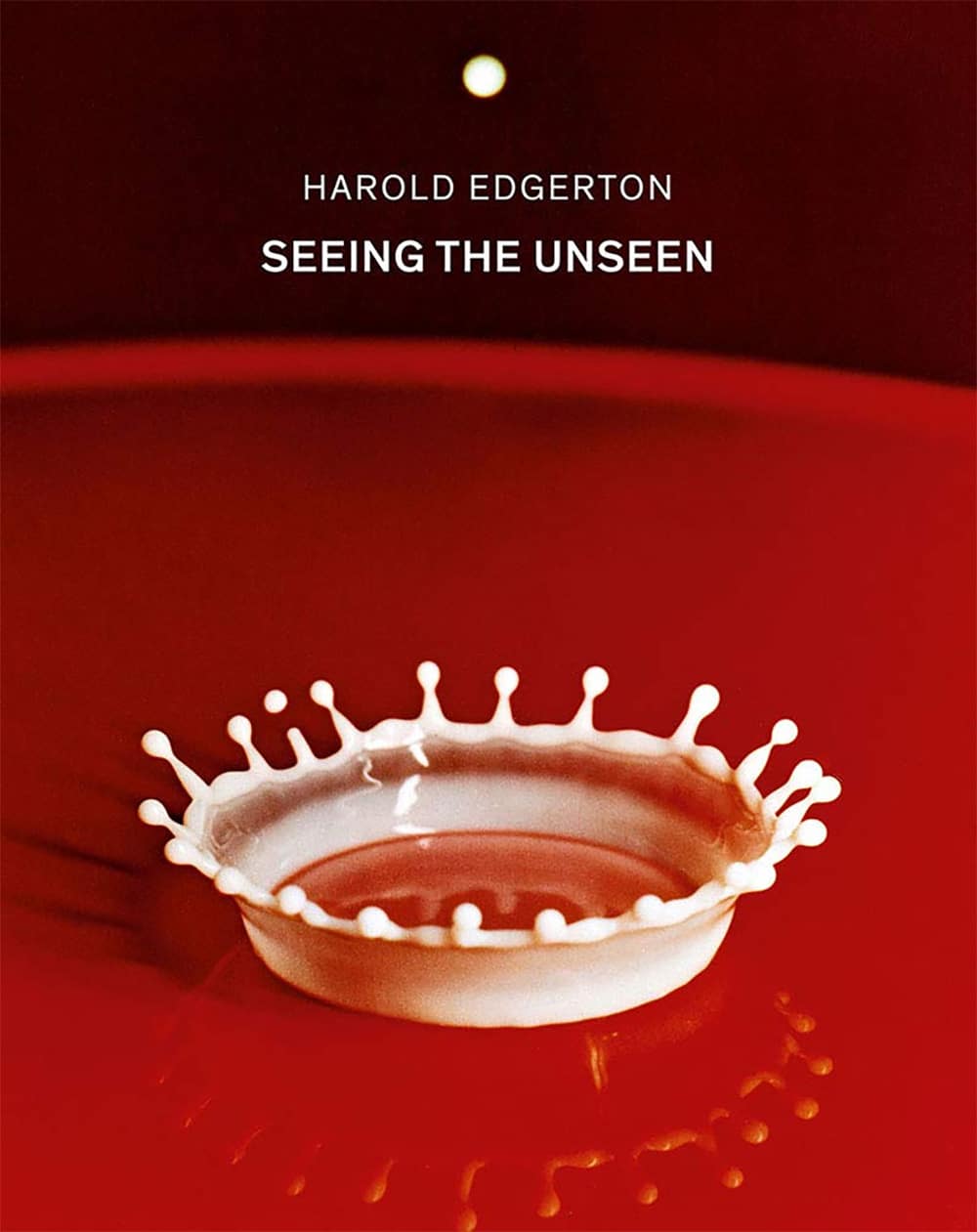

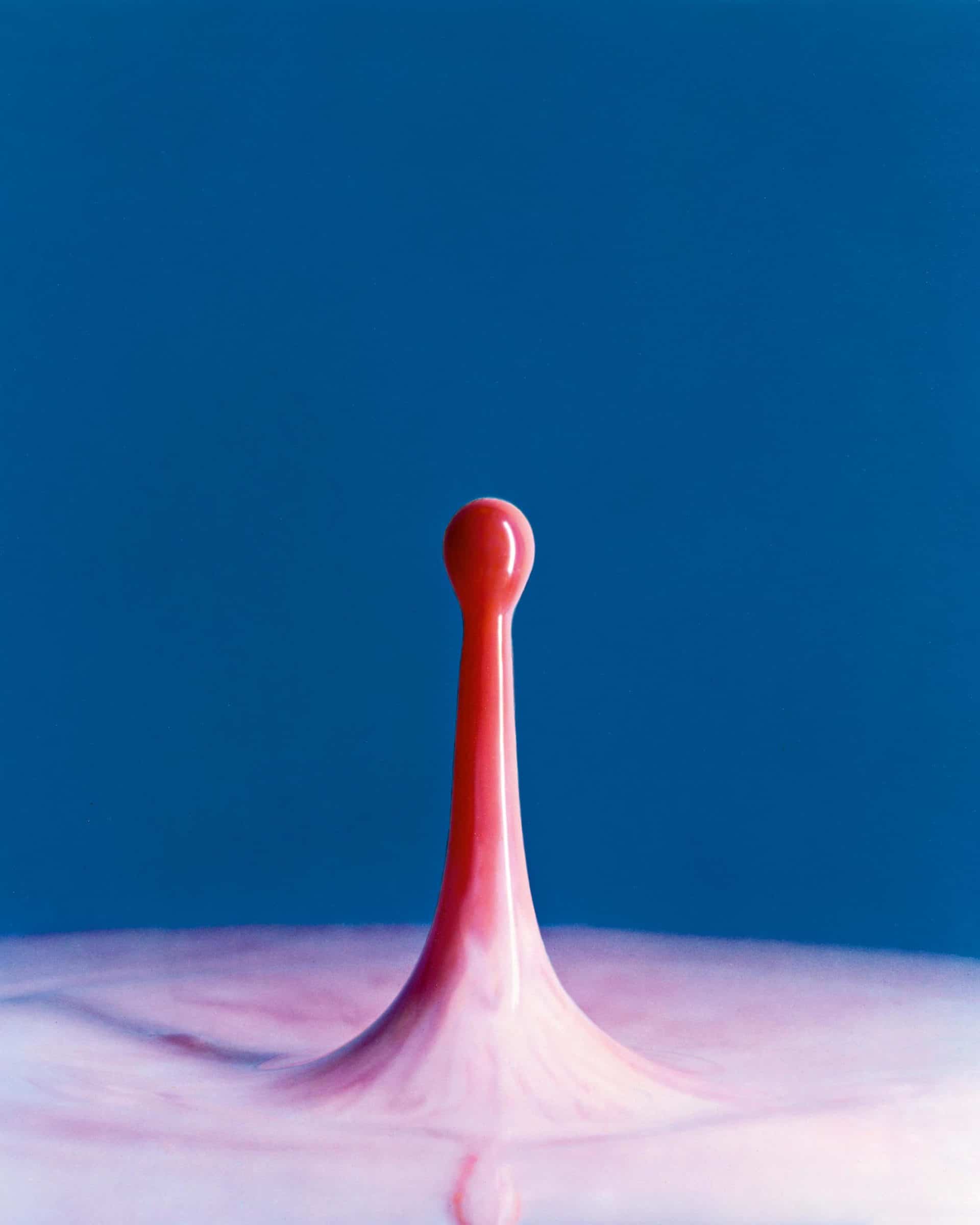

On the evening of Jan. 10, 1957, Harold Edgerton set a 4,000-volt electronic flash of his own design to the right of a small, shallow pool of milk in his “Strobe Lab” at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Edgerton, an electrical engineering professor, then released a drop of milk from a funnel 8 inches above the pool, reflecting a bright red background. A motion trigger was delayed a fraction of a second in order for the powerful flash to record the thumbnail-sized crown of the drop’s splash a few milliseconds after it hit the pool’s surface.

BOOK REVIEW — “Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen” (Steidl/MIT Museum, 224 pages).

Like any good scientist, Edgerton recorded his data in his notebook. He had first done a successful milk drop photo two decades before in black and white, but kept trying to perfect the shot. His goal was to record equally spaced droplets around the ring. Working with color film that was less sensitive to light made matters more difficult, and when he first saw the color film version of the milk crown, he said it was merely “acceptable” because the droplets were not perfectly spaced. However, to viewers around the world the photo was stunning. In 2016, Time magazine selected “Milk Drop Coronet, 1957” as one of the 100 most influential images of all time, claiming that “the picture proved that photography could advance human understanding of the physical world, and the technology Edgerton used to take it laid the foundation for the modern electronic flash.”

It has been nearly three decades since the death of Edgerton, often called the father of high-speed flash photography. A fresh look at his pioneering work, “Harold Edgerton: Seeing the Unseen,” includes more than 100 photographs and newly released selections from his notebooks, accompanied by essays by former colleagues and curators of the Edgerton photo and strobe archive at the MIT Museum.

Edgerton was born in 1903 and spent most of his early years in Nebraska. In 1925, he graduated from the University of Nebraska with a degree in electrical engineering. A gifted student, he was offered a position at General Electric and then decided to pursue graduate studies at MIT. For his post-graduate research he used a new apparatus called a Stroborama, invented by Laurent and Augustin Seguin, to study the motion of propellers and motors. Working with the New England Power Company, he found that the Stroborama could be used in a darkened room to synchronize the movements of their large motors, making power generation more stable.

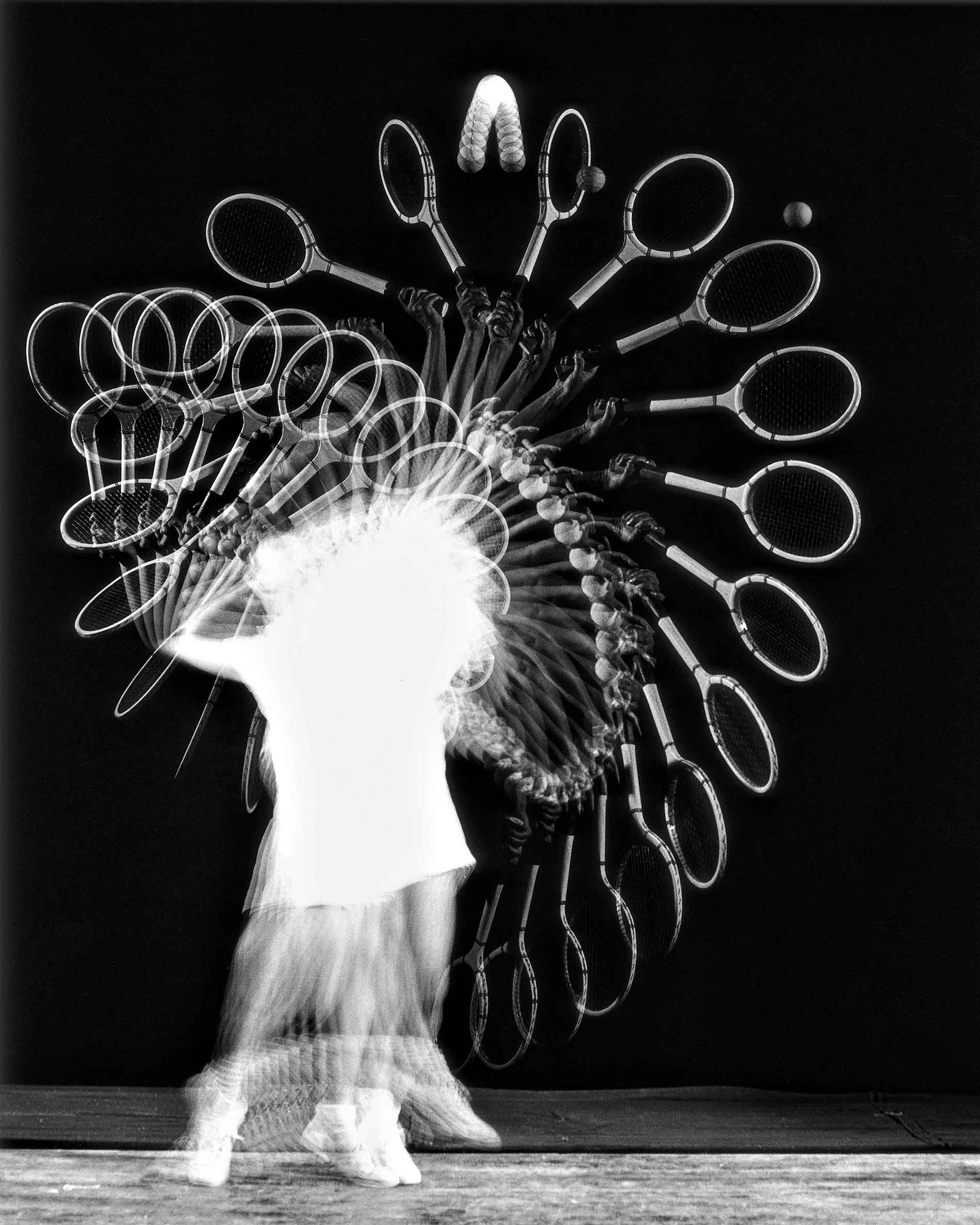

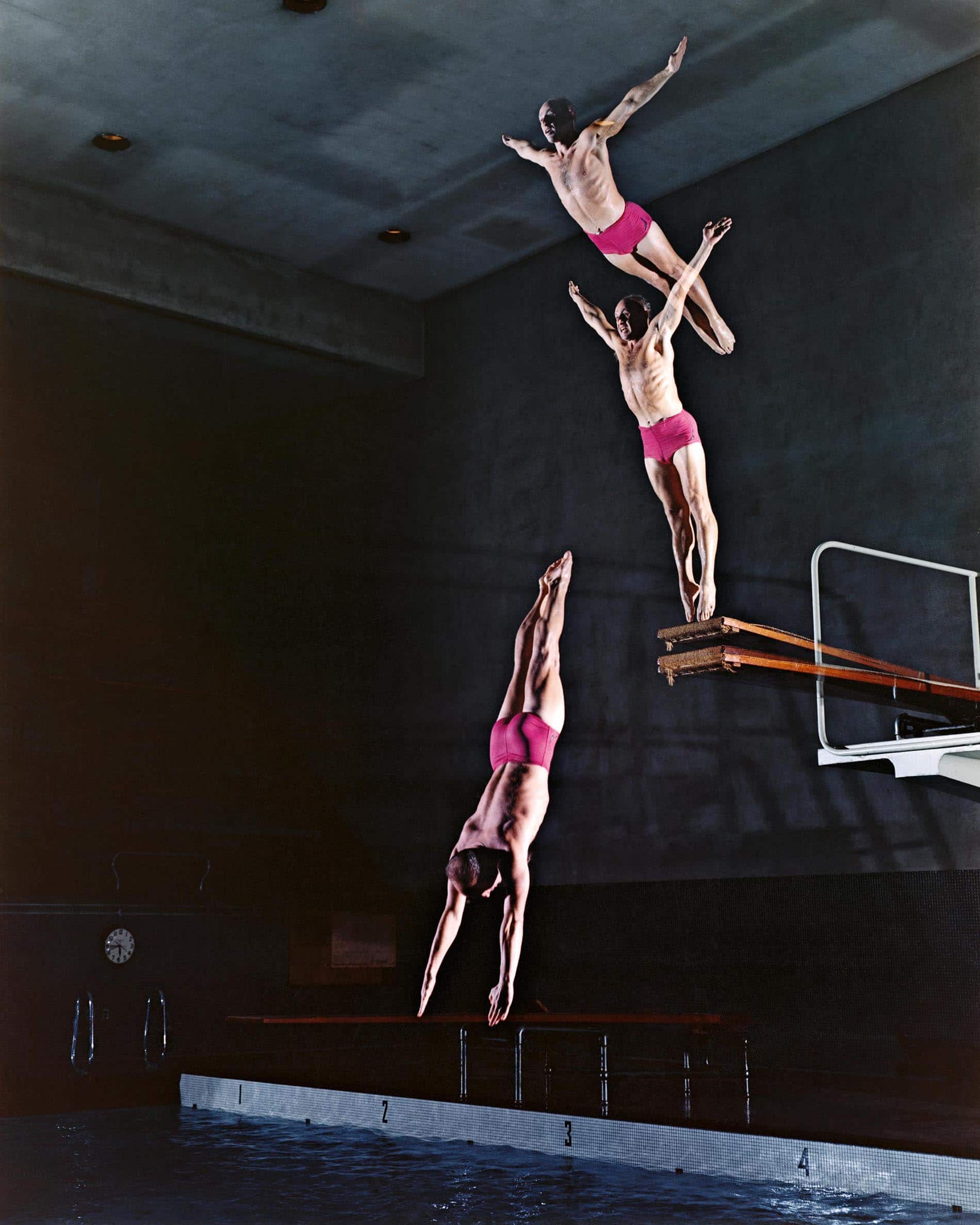

These newly invented strobes were not powerful enough or of a short enough duration to be used for photography, but Edgerton modified them to be able to freeze motion on a piece of film. At first, he used his custom flash just to make a record of scientific data. In 1932, he began his first “non-research” photos of water flowing from a laboratory faucet. He then moved into photographing the impact of falling objects, such as a shattering coffee cup and birds in flight, before creating an extended series depicting motion in sports. These images show not only the movement of athletes but also the bend of a golf club, bat, or racquet on impact and the resulting depression of the ball.

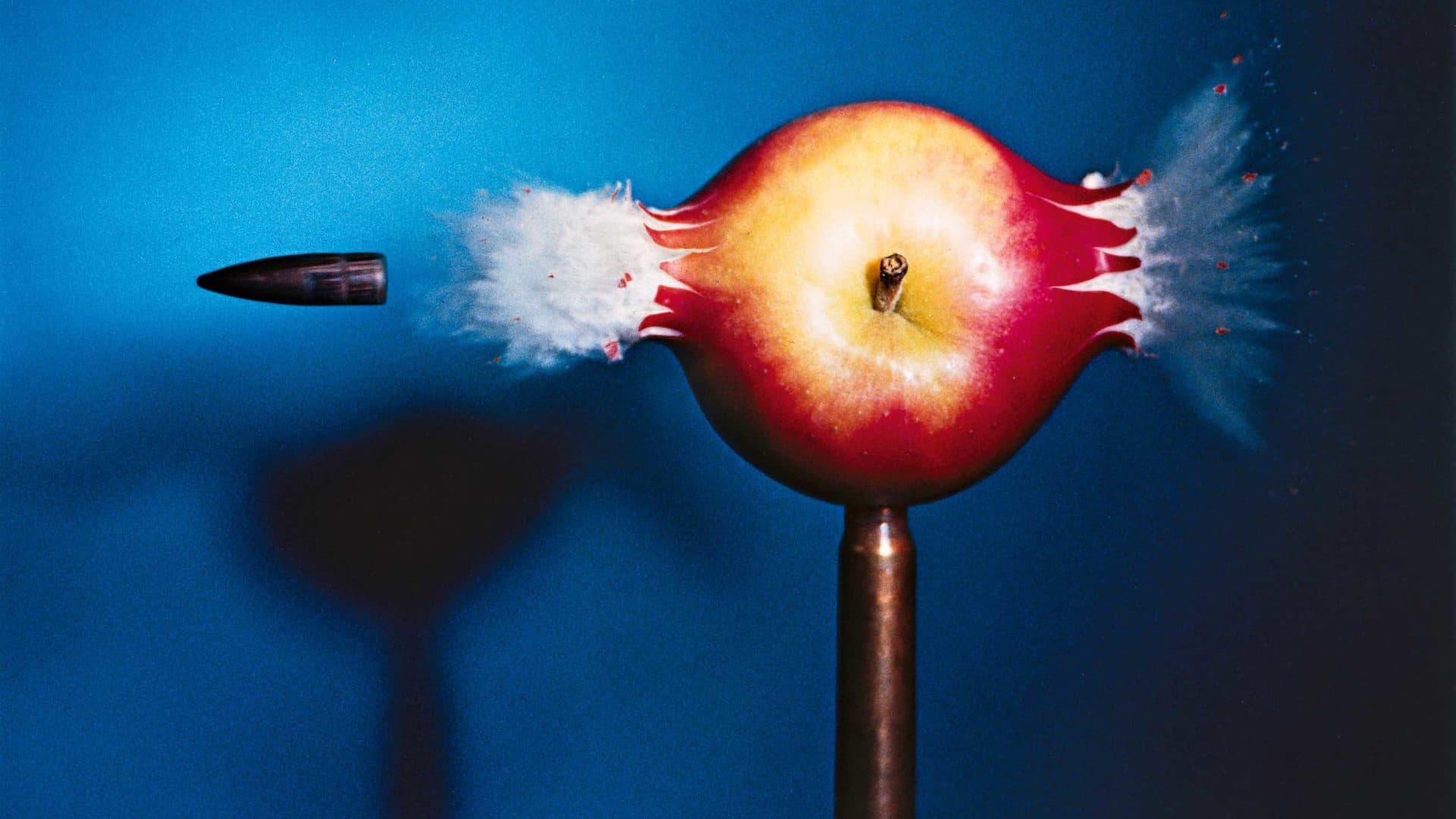

The physics of these forces had been theorized but never photographed before. Later, with the development of even more sophisticated flash equipment, he photographed bullets exiting a gun or exploding through apples, bananas, or balloons.

Long before Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson, Edgerton helped to popularize science for a general audience by capturing the remarkable in ordinary events. Yet despite his success and widespread acclaim in the photographic and art worlds, Edgerton insisted that: “I am no artist. I am an engineer after the facts.”

In addition to highlighting Edgerton’s photographic achievements, the book offers insights into his legacy as an ebullient educator. A plainspoken Midwesterner known to many as “Doc,” Edgerton was a product of a bygone era when professors wore ties in the lab. Summing up his life philosophy, he was known to say, “Tell everyone everything you know, seal a deal with a handshake, work like hell, and have fun.”

Peter Essick is a National Geographic photographer and specialist in environmental themes documenting human impacts of development on the natural landscape. His own images have been featured in Time magazine’s “Great Images of the 20th Century” and in “100 Best Photographs of National Geographic.”