Tackling the Burden and Shame of Hearing Loss

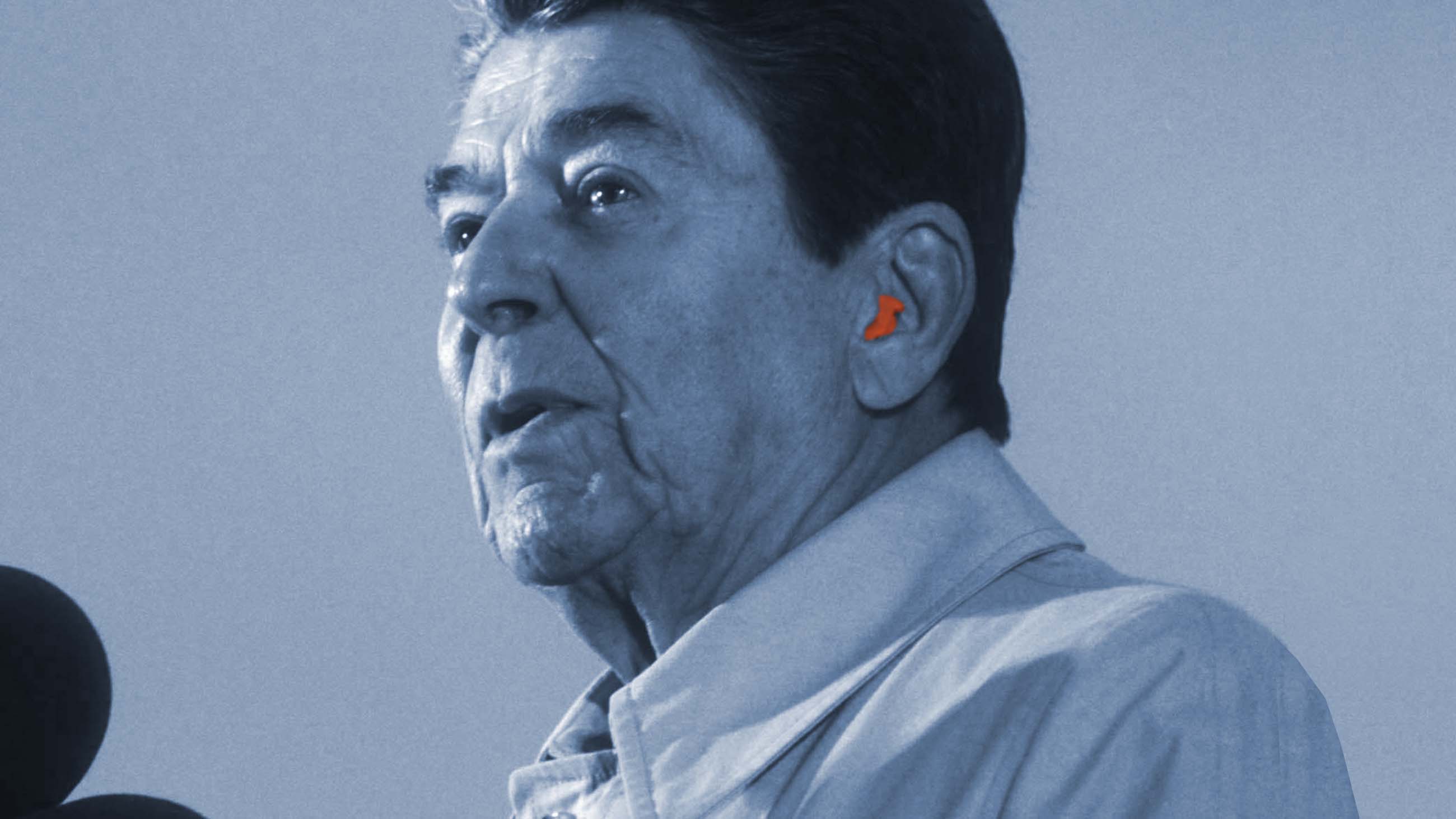

In 1983, The New York Times published a bombshell report about President Ronald Reagan: Starkey Laboratories had fitted the President, then 72, with a hearing aid. The news was welcomed by health professionals who reckoned it could help to reduce the stigma associated with hearing loss. At the time, one in three people over the age of 60 was thought to have hearing problems, though only around 20 percent who needed hearing aids used them.

Indeed, Reagan’s handlers knew too well that the revelation risked making the president look like a feeble old man — and worse, someone ill-equipped to run the most powerful nation on earth. “Among Presidential advisers,” The New York Times noted, “Mr. Reagan’s use of a hearing aid revived speculation on whether his age would be an issue if he seeks re-election next year.”

Reagan won re-election, of course, but nearly 40 years later, negative perceptions persist — and health advocates are more concerned than ever. Hearing loss, they say, is not just a functional disability affecting a subset of aging adults. With population growth and a boom in the global elderly population, the World Health Organization (WHO) now estimates that by 2050, more than 900 million people will have disabling hearing loss. A 2018 study of 3,316 children aged nine to 11 meanwhile, found that 14 percent already had signs of hearing loss themselves. While not conclusive, the study linked the loss to the rise of portable music players.

The problem is compounded by the fact that people with hearing loss are at greater risk for a host of other problems: social isolation, abuse, depression, lower overall incomes, restricted career choices, and occupational stress. A 2017 Lancet Commissions report named hearing loss as one of the largest potentially-modifiable risk factors for dementia, and the WHO estimates that unaddressed hearing loss comes with an annual global cost of at least $750 billion.

The crisis now has Starkey Hearing Technologies (the company changed its name in 2011) — and a growing and competitive field of scientists, drug developers, technology companies, and venture capitalists — angling to head-off the intertwined problems of hearing damage and cognitive decline. “Hearing loss has always been the poor step-sister of disabilities, and people still make fun of it,” said Karl Strom, editor in chief of the trade publication The Hearing Review.

“But it’s a serious disability,” he added “and has been linked to everything from cognitive function disabilities [such as] Alzheimer’s to depression and loneliness and a raft of comorbidities from diabetes to ischemic heart disease.”

And yet, just like Reagan’s worried handlers, the specter of hearing loss is still often greeted by many people with denial, shame, and reluctance to seek out solutions. The Hearing Loss Association of America reports that 48 million Americans currently have hearing loss, making it the third most common chronic ailment in the United States — ahead of diabetes and cancer, according the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC also lists occupational hearing loss from noise exposure as the most common U.S. work-related illness. Despite that, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) says only one-fifth of people who could benefit from a hearing aid seek it out.

Overcoming the sense of stigma is one of the main challenges facing researchers and technologists looking to curb hearing loss with new drugs, or to restore hearing in those who’ve lost it with a new generation of high-tech devices. Should they succeed, the payoff — both financial and social — is potentially huge.

“The way I do the math, a third of all adults have unaddressed hearing issues,” said Kevin Franck, audiology director at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, a Harvard-affiliated teaching and research hospital. “That’s lot of people.”

The inner ear is filled with thousands of microscopic hair cells. When sound waves hit these hair cells they vibrate, creating electrical signals that reach the brain through the auditory nerve. Today, hearing loss is attributed to a number of factors, including presbycusis, which can be caused by the natural cell deterioration that comes with aging. Noise-induced hearing loss, or NIHL, is also a major factor, as are medications that, as a side effect, can cause damage to the hairs of the inner ear.

“If you are a venture capitalist,” Franck said, “you get very excited about those numbers.” But helping people who have experienced hearing loss “is not as easy as selling them an app or a pair of headphones,” he added. “It’s more complicated than that.”

One potential breakthrough may come from a handful of drugs currently being tested to combat hair cell damage from ototoxic drugs. Scores of medications used to treat everything from infections to cancer to heart disease can kill off these cells. Currently Boston-based Decibel Therapeutics has two drugs to counteract these side effects — small molecules administered via transtympanic injection or taken orally — in Phase I clinical trials.

“Cisplatin and aminoglycoside antibiotics are powerful drugs, which unfortunately often come at the expense of the delicate cells in the inner ear that are necessary for hearing and balance,” Decibel’s chief medical officer Peter Weber wrote in an email. “We hope to change the equation for clinicians and patients by preventing these medications from damaging the inner ear, without interfering with the lifesaving efficacy that they are known for.”

In Woburn, Massachusetts, Frequency Therapeutics has begun Phase I and II trials with a potentially broader solution. The company’s regeneration platform offers hope for those with NIHL, presbycusis, and other forms of hearing loss. Its process involves progenitor cell activation — in essence, coaxing cells back to their development phrase to get them to generate more hair cells.

“I’m a drug developer by trade and have been in the field for about 30 years and I’ve been pretty bearish on regenerative therapies,” Frequency Therapeutics chief development officer Carl LeBel said. But now, he says, the company can stimulate stem cells in the ear, which in turn regenerate the more specialized sensory cells. “Up until today no one has been able to crack the nut about how we can regenerate that function,” LeBel said. “That’s why we are so enthusiastic about our technology.”

LeBel sees the company’s platform as potentially applicable to multiple sclerosis, alopecia, muscle regeneration, and a wide swath of autoimmune diseases. But others caution against looking for miracles in the coming months. “For my entire career, they’ve been five years away,” Franck said.

“Something has happened where I do believe that, after these 20 some years I have been in the profession, they are closer,” he added. “But they always seem like they’re right over the horizon.”

While drug developers are focused on regeneration, hearing aid manufacturers are aiming to make their devices as indispensable as smartphones — not just for those with hearing impairments, but for everyone. Other functions, beyond improving hearing, “would make the non-hearing aid person jealous that they don’t have one,” said Bill Facteau, the president and CEO of the California-based hearing-aid developer Earlens. “That is going to be the game changer.”

Earlens developed technology to convert sound information into non-visible light that activates a lens on the eardrum to vibrate it, which the company claims conducts sound more efficiently. The innovation represents only a sliver of the advances hearing aids have made in the past few years. Many can now be connected to mobile devices to allow wearers to stream phone calls, TV programs, and music, while directional microphones can improve everyone’s hearing in crowded restaurants, on windy hikes, or at any noisy event.

At the higher end of the spectrum, these features can be fine-tuned with phone apps, some of which adapt to make automatic adjustments as the user moves from one type of noise environment to another.

The Arizona Hearing Center breaks down the basics of a new hearing aid called Earlens.

At Starkey Hearing Technologies, chief technology officer Achin Bhowmik helped to develop the Livio AI, which doubles as a FitBit-like health tracker, a fall detection sensor, and a language translator that transcribes speech to text on your phone, among other functions. The company also added brain-health features that track daily social engagement and active listening. Although at least one 2019 study linking losses in hearing and cognitive function failed to find social engagement as a factor in staving off mental decline, Bhowmik thinks this added functionality could help combat dementia and Alzheimer’s.

“Your FitBit or Apple Watch has no clue whether you are socially engaged,” Bhowmik said.

“It was a slam dunk for me to integrate those features into the hearing aid,” he added.

For all their efforts, Earlens, Starkey, and other industry players — Widex, Phonak, Oticon — may face new competition for their creations. In October, the FDA approved the first direct-to-consumer hearing aid, which unlike the standard audiologist-fitted device, can be fitted by the user. The product, developed by Bose, must still comply with federal and state laws relating to the sale of hearing aids, though the FDA is also currently drafting regulations for a new category of hearing aids that can be sold over the counter.

All of this is aimed at increasing access and reducing costs. As it stands, Medicare doesn’t cover hearing care or hearing aids, and the average price of a single aid comes in at around $2,400. High-end offerings often double that.

Bhowmik believes the ballooning number of customers and competitors will naturally drive down costs. “Look at the hearing aid market and 15 million hearing aids sold by the entire industry [per year],” he said. “Imagine a world where I can drive the volume up 10 times, and what I can do to the economics of them.”

For his part, Franck doesn’t know if treatment costs will come down fast enough to meet the rising need. But he does see the potential for a new generation of aging adults that won’t tolerate the once-thought-to-be inevitable decline that past generations accepted.

“They are going to demand greater performance from hearing for longer in their lives,” Franck said. “Some people take hearing loss as something that just happens when you get old. I think this generation might say, ‘I don’t care if I have to wear something on my ears, I’ve already been wearing stuff on my ears.’”

Whether that sort of shameless embrace of hearing-loss and hearing aids will come to pass, of course, remains an open question — not least because unease clearly persists.

When Bhowmik joined Starkey Hearing Technologies in 2017, one of the few things he knew about the company was the legendary story of Reagan’s hearing aid. A veteran of Intel, where he was vice president and general manager of the perceptual computing group, Bhowmik quickly learned that innovations in the field of audiology rivaled anything happening in Silicon Valley. Scientists working on hearing loss had their fingers in everything from artificial intelligence to stem cell therapies.

But when former U.S. President Bill Clinton came to the company recently to be fitted with new hearing aids, Bhowmik also learned that pride remains a barrier to seeking help with hearing problems. During a visit with Clinton, Bhowmik says he showed him Starkey’s latest hearing aids. The devices come packed with radically-advanced technology — light years ahead of what Starkey had offered President Reagan decades earlier — but they remain too large to fit discreetly inside the ear.

Clinton wasn’t interested.

“He still likes to use our invisible, in-ear canal device nobody can see,” Bhowmik said. “If president Clinton doesn’t want anyone to see his hearing aids, there still is some stigma.”

Jed Gottlieb is a Massachusetts-based writer whose work has appeared in The Boston Herald, Newsweek, Fast Company, Billboard, Quartz, and the Columbia Journalism Review, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I agree one hundred percent Edward, I would be right behind you in the front of the euthanasia queue! I am very suicidal because of tinnitus and acute hearing loss, the tinnitus is so loud it sounds like a huge gong on a mountaintop. It is constant, 24 hour a day seven days a week for the last 5 years. I avoid social situations with my husband, he is humiliated by my disability. If we go to a restaurant it is rare that I eat, I am so afraid I will miss what he is saying.

I hope this does not come off as self pity, it’s just how it is.

This very good article missing one important new direction, Consumer Electronics devices that look and work as Bluetooth headsets or earbuds, but additionally include hearing enhancement functionality. Wear&Hear BeHear Now, BOSE Hearphones and NuHeara IQbuds are three prominent examples that one can purchase today. BOSE has already received FDA clearance for an unidentified, self-fitted hearing aid that paves the way for others. Actually, this is already implemented in BeHear NOW and IQbuds. The devices are currently larger than conventional hearing aids, but they remove the stigma of wearing a hearing aid by not looking as aid, but rather as communication or audio device. In any case, with a little more advance in CE chipsets, CE industry will be able to create small, in-ear audio devices and the corresponding software will allow sound personalization with hearing enhancement. All affordable, cool looking and high performance.

This article is an interesting example of people talking past each other. Those involved in the hearing loss industry talk about the benefits of hearing aids and how it should be a priority in peoples lives. Those in the hearing loss consumer population segment talk about costs they can’t afford. (The overlap with expensive dental care is a small but significant fraction).

There are also failures to communicate. People considering hearing aids need to be aware of the life cycle costs and the average annual cost of hearing aids. To read most articles, this one included, you just cover the upfront capital costs and a few batteries, and voila, you are good to go. Not so. There are annual upkeep and maintenance, replacement of devices every few years and some other expenses that depend on technology and patent condition.

There seems to be little to no advocacy for health benefits for the hearing impaired. As usual, there is no free market to provide incentives for cost and price reductions. The AARP has the heft to help here, both in terms of advocacy and information. Perhaps they could turn it into a social justice issue?

I am hearing impaired since birth and work as a hearing specialist by trade. I went my first 30 years with no help, and was shocked at how much my life changed for the better when I finally got my first set. This is why I got into this field, as well as getting access to the best technology every year. I can tell you from experience that hearing help is absolutely essential and life changing, and the negative effects are far far greater than most people ever realize. I can also tell you that when I was someone coming into this who just wanted to hear better, I had no comprehension of everything involved. I have been working in this field 10 years now, and would like to share some of my knowledge and observations here.

People want to say that hearing aids should be much cheaper, akin to other consumer electronics. What they fail to realize is that hearing aids are high maintenance medical devices that must be completely customized to every single person in order to get you the results you want. No two ears are the same, not even on both sides of the same head. No two people hear the same way or have the same lifestyle considerations or same physical dexterity. So to try and churn out a singular device that will help all people is just not possible. Each device, even when it looks the same on the outside, has to be custom fit and programmed to each individual person in order to help them hear the best that they are capable of. The complexities of sound and hearing must be taken into consideration, and most people have approximately zero knowledge about any of it. They think it’s a simple thing, stick something in your ear, hear better. Oh how I wish!

There is an incredible amount of research and development that is going into this field every single year, as we know we are still not replicating the sense of human hearing and we are trying to get closer and closer. Hearing is our most complex and complicated sense and understanding is a brain function, so it’s just not an easy thing to do. If it were easy, it’d already be done and we wouldn’t be having this conversation.

The economies of scale also do not really come into play because there is such a small market compared to the research and development costs. Apple sold more iPhones on the first day they were available in 2018 than the entire hearing aid market sold around the world all year in 2018… and the iPhones are all exactly the same, whereas hearing aids by nature cannot be. It is just not a comparable market. Also, people fail to realize how difficult it is to do all the computing and processing necessary in a device the size of a hearing aid on a tiny battery that is expected to last at least a week in an environment that is 98 degrees 100% humidity. So there are certain factors at play here that people do not understand that conspire to make “cheap” hearing aids that do every single thing people want them to do technologically out of reach… though perhaps not forever. Over the last 10 years that I’ve been a specialist, the strides forward made in hearing aid technology have been absolutely incredible. Hearing aids have changed more in the last 7 years than they have in the last 70.

Furthermore, most people wait far too long to get help for their hearing. This means that due to a process called auditory deprivation, a permanent irreversible loss of understanding has happened because the brain has not received the essential sound stimulation it needs for too long. The parts of the brain responsible for comprehending the speech have deteriorated, so this means that even when we get the sound loud enough, the comprehension is no longer there. This is a permanent process. Once the brain reorganizes, atrophies and deteriorates, we cannot get that comprehension back. This is never the fault of the person who waited too long to do something, it is always the fault of the devices that can’t compensate for the irreversible changes that have happened because the person waited too long. The only time we can get back to 100% understanding is when we treat the problem when it’s mild and keep it treated as it progresses. People want to blame the devices because that’s easy and it shifts responsibility for the problem to the “hearing aids that didn’t work” and away from them. If you wait until the problem is severe and has been going on for years, NO amount of money or technology is going to bring back the understanding you are missing. Hearing is a brain function, and it is a use it or lose it proposition.

Also, let’s talk about the high maintenance part of the equation. I take care of my clients on average between 3-6 times per year for deep cleaning their hearing aids, removing wax from ears, replacing parts like microphone covers and wax filters, doing repairs, performing updated hearing tests and adjustments to the devices. My minimum appointment length is 30 minutes, and I frequently spend 1-2 hours with clients at a time providing care and counseling, especially in the beginning. The care I provide is bundled in to the cost of the devices so that people don’t have to be afraid of what it will cost when they need my services. We used to belong to the TruHearing network, which lowers the cost of the devices by unbundling them from the cost of the services. What I found is that people STILL thought the hearing aids were very expensive, and then skipped the necessary services to keep them working well in order to “save money”. Many of these clients would go a year or more and then come in reluctantly, and all upset because “these devices haven’t been working for months, and I can’t even wear them! What are you going to do about it, it was a big rip off!” So I use my video otoscope, which magnifies everything 150x and puts it on the big screen TV and show them, hey look, here’s wax in your filters, your microphone covers are plugged, and hey there’s wax in your ears too. Clean clean clean, replace filters, make some adjustments, and Presto! They’re working like new again! The professional maintenance is so necessary to keep them working because in my experience, most people don’t have magnification at home to be able to see the clogs in the tiny parts and pieces, nor do they have the ability to look inside their own ears, and they certainly don’t have the kind of cleaning tools that I have to be able to properly maintain the hearing aids at home. As a professional, I much prefer the plan where people pay one price up front and then they’re never afraid to call me and say, hey, I’m not hearing well, can I get an appointment? And then I just have the freedom to do what is needed in my office to get things working again without nickel and diming them for every single service performed. Imagine how much better medical care would be if when you got a pacemaker, the cost of the necessary services to keep them working were included for as long as you had the pacemaker? But they are not. The only reason you don’t mind is because insurance picks up most of the bill.

It is a shame that insurance companies either leave us on our own with this expense, or are starting to provide coverage but doing it through adding another middle man like TruHearing which is dictating the terms and charges to the point that hearing professionals are not able to provide the necessary quality care at a price point that allows us to continue to be in business. It costs money to run and staff and equip an office to be able to provide this care, but people forget that these services cost because we have bundled for so long. People think it’s all the devices when it’s not. Hearing healthcare is actually one of the most cost effective and life changing forms of healthcare out there, but it is out of reach for many simply because insurance doesn’t help. More and more studies are coming out showing how truly necessary hearing care is for proper brain function and overall health and wellness. These studies are showing that leaving hearing untreated causes a cascade of negative health effects that causes people to have 46% higher overall medical expenses and decline in quality of life and independence, compared to having normal hearing. Hearing aids mitigate this risk significantly, and are absolutely necessary to living our best life.

There are many ways to put hearing aids within reach. Payment plans are available that allow you to spread the cost over time. Lower cost basic devices are available as low as $699-$999 each which rival the cost of devices on the internet (Eargo / MDHearingAid) and also include the necessary services to customize them and keep them working for you long term. If you truly cannot afford a hearing device at any price, programs like Hear Now through the Starkey Hearing Foundation provide hearing aids on an application basis to those in need. There is help for everyone out there, sometimes it just takes a little extra digging to find the providers with inexpensive options. An inexpensive hearing aid is far better than no hearing aid, however if you want the more advanced features, cell phone connectivity, performance in noise, invisible options, you must be prepared to pay more premium prices. With hearing aids, as with all things in life, you can either have low cost or you can have high performance, you can rarely have both.

I also want to point out that hearing aids are the only medical care that comes on a trial basis with a money back guarantee. In my office, when I fit a new client and spend 2 hours testing/selecting/counseling/educating the client at first visit, 1 hour fitting and teaching them how to use their hearing aids, 2-3 visits for follow up adjustments/counseling/teaching to maintain, and if the client is not happy at the end of 6 weeks, they get back 100% of their investment and I get nothing for the time I spent. What other medical provider provides those kind of services and offers a money back guarantee if your treatment does not work? None of them. We are also the only medical care where you pay one time and get services for years after the fact without additional service charges. No other medical provider does that. I happen to think that these are wonderful things that the hearing aid industry does that no other medical provider does, and we still are regarded as little more than “used car salesmen looking to rip off old people with exorbitant pricing”. We provide necessary and life changing services/devices for pennies per day, and the only way to make hearing aids truly work for people is to customize them. There are zero one-size-fits-all cheap solutions to hearing loss and based on the complexities of the problem we are attempting to help, I doubt there ever will be.

I will end with a quote, I don’t know who said it but it was hung up in a store I visited. “The bitterness of poor quality remains long after the sweetness of a low price is forgotten.” AKA, you get what you pay for. Hearing loss deserves to be treated appropriately and professionally. Anything less is doing yourself, your health, your relationships, indeed your whole life, a terrible disservice.

Alina, I am a retired audiologist and you are SPOT-ON with your description of the current state of hearing health care in America. The cost of hearing devices and the professional care necessary to fit them effectively, train the user in their use and care, and provide ongoing maintenance to keep them functioning optimally is actually quite low when compared to other medical treatments.

The difference is that insurance insulates us from knowing the true cost of most medical care, and when we are faced with the high cost of health services not covered by insurance, it DOES seem exorbitant. I remember a patient of mine who said she could not afford hearing aids at the time because she had just spent $12,000 in dental work!

There is no easy solution. Insurance companies that refer their clients to third party administrators like TruHearing that contract hearing care providers to provide cut rate services are doing no favors for their customers. To do things right, corners cannot be cut.

After 40 years as an audiologist, I am discouraged that hearing loss Is still not seen as a serious disability and stigma issues are still very much a factor in people not wishing to get hearing aids – and this is true even in countries that have universal healthcare that covers hearing aids! However, I’m hopeful that new developments in hearing healthcare will make a real difference so that more people can experience the many benefits of getting help for hearing loss.

The cost of hearing aids is outrageous. Such a simple device should not cost $3500, as I paid. I was shown a chart with one set for $1700 and another for $5200. I was told that the best choice was the midrange priced pair. I found out later my mother- in- law was scammed the same way in the same audiology office.

When has a medical device or drug recently gone down in price in the U.S.? Never believe a business person who ‘promises’ such a ludicrous proposition.

Also, having tracking software in hearing aids is another opportunity for a business to know everything you do. Phones and the internet track our purchases and online history. Will businesses be able to hear what we hear and say? Let’s not give away the rest of our lives to corporate interests.

Good article that covered all the bases, but I do wish the author — and Kevin Franck — had mentioned the Hearing Loss Association of America, which is working hard with federal regulators and others to help bring the price of hearing aids down, to help make it easier to find a hearing-aid provider and get hearing aids, and to ensure compliance with the Americans with Disabilities ACT for people with hearing loss. HLAA was a significant contributor to the FDA’s discussion of over-the-counter hearing aids and continues to work with the FDA through the comment period before OTC aids go on the market. Through local chapters, including several in the Boston area, HLAA provides information, education and support for people with hearing loss. The letter writers below, especially the poor man suffering so from tinnitus, might find some new ways to deal with their disability. I serve on the HLAA board with Kevin Franck. Although the affiliation was probably lost in the editing, I’m sure Kevin would agree with me about the value of HLAA’s work nationally and locally.

I credit apple’s wireless earpods for normalizing hearing aids among the younger set. Those earpods look like in-ear hearing aids with twigs, varnished white. I’m sure the twigs serve as the mark of coolness right now. Meanwhile, I blend in with a sleek behind-the-ear silver model – no twigs, no wires. :)

Please don’t dispear. Things in the hearing loss world are getting better, I have a profound hearing loss and have learned so much to help myself. Fighting hearing loss is not totally dependent on hearing aids or cochlear implants. Fighting hearing loss really needs a three legged attack. Aids can not do it all. You also need strategy and technology. Neither of these are expensive and really cost little or even nothing. By strategy I am talking about things like where to sit in a restaurant to find the quietist spot or a way of having your spouse/partner learn and use something called Clear Speech. And some technology such as a new app for android phones called Live Transcribe that turns speech to text is FREE . Where did I learn most of this through the Hearing Loss Association of America. Seek out a local chapter. They even have a program called N-CHATT where a speaker can come and address your church or civic or other group on hearing loss ( I am in trading o be come one);Pleae Don’t dispear.

I think that the focus of this article is off base. Vanity is not the main deterrent for most people—it is the price. The decline in my hearing factored into my decision to retire, but as a retiree—with a pension and Social Security—most hearing aids are beyond my budget. Should I go into savings for something that may or may not actually help me with my particular hearing deficiency? These expensive little gadgets come with few guarantees. The great breakthrough that will make hearing aids costs hundred, not thousands, or dollars has been promised for at least five years. I am still waiting.

This is FASCINATING and incredibly encouraging, Undark, thank you! I hadn’t thought this kind of treatment would be available for the foreseeable future, and it’s nice to see it getting a step or two closer to reality.

I can’t speak to the cost issues in the U.S., except to point out that hearing aids are easier to pay for here in Canada, and in any other country with universal health care coverage…in other words, every other industrialized country on the planet.

BUT that’s not the comment I actually wanted to share, until I read the previous ones. Mine has to do with the stigma around hearing loss, and the frustration and social isolation that can go along with losing your hearing.

The audiologist who first diagnosed my hearing loss about a decade ago was far more concerned with giving me aids that weren’t visible than with finding the model that would fit my hereditary pattern of deafness. Needless to say, my first step to getting the right aids was to find a new audiologist.

But I appreciate that moment in retrospect, not only because I finally had a diagnosis, but because it got me thinking about how and why the stigma developed. We mostly accept that our eyesight will fail with time, and while I don’t have data for this, my impression is that most people who choose contact lenses over glasses do so for convenience, maybe for cosmetics, but certainly not out of a sense of shame.

So why is it shameful to lose our hearing? Again, this is just speculation, but I think it’s because missing one or many beats in a conversation makes you look stupid, and that points back to the time when we used to talk about people being “deaf and dumb” (with “dumb” as a synonym for “mute”). I don’t think it’s impossible that we tend to confuse the two, and for many people who lose their hearing, the first impulse is to either deny it or hide out.

I’ve found that it’s a lot more productive, and it *almost* always works, to let people know what’s going on and enlist their help. It usually lands well when I get a chance to suggest that, while there are a great many reasons to suspect me of being dumb, my deafness is not one of them.

As recently as yesterday, I was giving a talk on a contentious, urgent topic where the details matter — climate change communication — in an open-concept space with a lot of background noise. I explained right off the top why I might have to ask people to repeat their questions, then got them to consistently shout their comments so that *other participants* across the room could hear. Being pro-active made me the canary in the coal mine for others who couldn’t hear parts of the session, either because they also had diagnosed or undiagnosed hearing loss, or just because the space was distracting and echoey.

Once in a while, I’ll run into someone who gets dismissive or resentful that I can’t easily hear every supremely important word they utter. Usually, it’s easy enough to silently, politely decide that they’ve self-selected, and it really won’t be necessary to interact with them ever again. On the other hand, I’ve also learned that when I hear someone say something unexpectedly funny, it’s often because I didn’t quite hear what they actually said — and if I tell them what I heard, they can set me straight after we’ve both had a good laugh.

Pricing of hearing aids seems to be a price fixing racket. All the top brands are priced about the same for ‘premium’ aids. That makes no sense unless there is some sort of collusion.

This country should be ashamed of how little is done financially to help the hearing impaired. All the technology in the universe won’t help If average people can’t afford to access it.

I have bilateral hearing loss and bilateral tinnitus my hearing loss is significant but i would rather be deaf, than endure life destroying tinnitus which i have had for 28 years i take max dose antidepressants , valium and a bottle of wine a night just to get some sleep but my feelings towards T are very aversive so mine is just an existance if i could get euthanasia i would be first in the queue

And yet decades later, getting hearing aids is still beyond the grasp of folks that can’t shell out anywhere from $600 to $7000. Shame.

Yes this is a sad situation. My husband can’t hear a thing,my failing health I need to call on him when I fall. And he can’t even hear my screaming. Medicare needs to start paying for hearing services.