VIEWPOINTS: Partner content, op-eds, and Undark editorials.

Newly unsealed documents from a lawsuit by the state of Massachusetts allege that Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin and other addictive opioids, actively sniffed out new, sinister ways to cash in on the opioid crisis.

Despite years of negative press coverage, unwanted attention from regulators, multimillion dollar fines, and several major lawsuits, Purdue staff and owners sought to expand the company’s sights beyond its usual array of opioid painkillers. Purdue planned to become an “end-to-end pain provider,” by branching into the market for opioid addiction and overdose medicines, looking to peddle these medicines even while the company continued to aggressively market its addictive opioids. Internal research materials coldly explained the rationale behind this plan: “Pain treatment and addiction are naturally linked.”

As thousands of Americans continue to overdose on opioids annually, Purdue’s secret marketing research predicted that sales of naloxone, the overdose reversal drug, and buprenorphine, a medicine used to treat opioid addiction, would increase exponentially. Addiction to Purdue’s opioids would thus drive the sale of the company’s opioid addiction and overdose medicines. Purdue even planned to target as customers patients already taking the company’s opioids and doctors who prescribed opioids excessively, according to the Massachusetts lawsuit filing. To keep the plan quiet, Purdue staff dubbed the scheme “Project Tango.”

The audacity of Project Tango enraged many observers. But considered in historical context, the news that Purdue sought to peddle opioid addiction medicines while continuing to sell opioids seems less surprising. In fact, there is clear historical precedent for Purdue’s business plan. Over a century ago, “patent medicine” sellers pioneered this strategy during the U.S.’s Gilded Age opiate addiction epidemic.

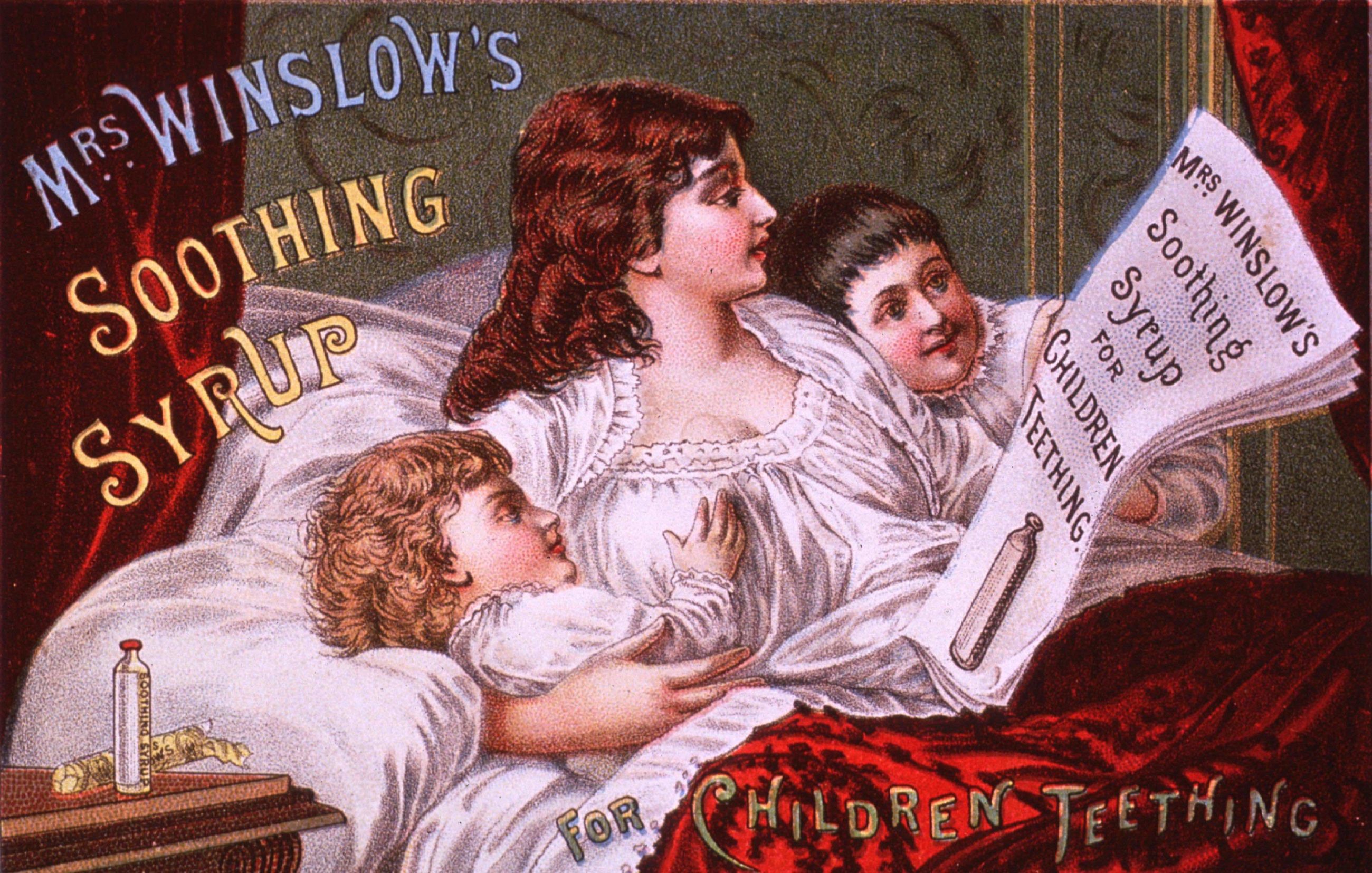

Opiates were some of the most commonly prescribed medicines in American history until the 20th century. Pills containing opium, hypodermic morphine injections and laudanum, a drinkable liquid concoction of opium and alcohol, constituted half or more of all medicines prescribed in American hospitals during most of the 19th century, according to research by the historian John Harley Warner. Opiates were also present in countless “patent medicines,” over-the-counter panaceas made of secret ingredients, often sold under catchy brand names like Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. Americans could choose from 5,000 brands of patent medicines marketed for all manner of ailments by the 1880s. In 1904, just before federal oversight began, patent medicines had matured into an astonishingly profitable industry, with estimated sales at $74 million annually — equivalent to about $2.1 billion today.

Opiate-laced prescriptions and patent medicines often caused addiction. The historian David T. Courtwright estimates that opiate addiction rates in the U.S. skyrocketed to 4.59 per thousand Americans by the 1890s — a high rate, although lower than the rate of fatal opioid overdoses in recent years. Most individuals developed addictions through medicines, rather than the infamous smoking variety of opium. Victims of “the habit” cut across demographic lines, encompassing middle-class housewives suffering from menstrual pain, Civil War veterans reeling from amputations and many others in between.

Yet even for those who became addicted to prescription opiates, the condition was socially stigmatized and physically dangerous. Like today, addiction to opiates often led to fatal overdose, condemnation and sometimes even involuntary commitment to mental asylums. As one doctor reported to the Iowa Board of Health in 1885, addicted people lived “truly in a veritable hell.”

To avoid these frightful outcomes, desperate, opiate-addicted Americans frequently sought out medical treatment for their condition.

Gilded Age Americans could choose from a range of therapies for opiate addiction. Wealthy patients frequented plush private clinics, where they could receive inpatient treatment for opiate addiction. The most popular were the Keeley Institutes, which offered patients injections of the “Bichloride of Gold” remedy, invented by the doctor Leslie Keeley.

Scores of Keeley Institutes sprang up around the country in the late 19th century, a testament to the popularity of Keeley’s “Gold Cure,” which he marketed for alcoholism and drug addiction. No up-and-coming Gilded Age city was complete without a Keeley Institute. At the height of the Gold Cure craze, there were 118 institutes serving 500,000 Americans between 1880 and 1920. Even the federal government had a contract with Keeley to provide the Gold Cure to addicted veterans. Although injections of the Gold Cure had little intrinsic medical value, historians believe that socializing with other like-minded patients in the Keeley Institutes may have helped some patients recover from addiction.

Keeley faced stiff competition, however. Other popular therapies for opiate addiction included patent medicine “cures” and “antidotes,” which were cheaper than inpatient care. These could be ordered by mail without a prescription, and consumed in the privacy of one’s home, away from prying eyes.

Fueled by high demand, during its heyday at the turn of the 20th century, addiction cures bloomed into a multimillion-dollar sector of the patent medicine industry. Dozens of pharmaceutical companies peddled their “cures” to willing, opiate-addicted customers, which they marketed through pamphlets, postcards, and newspaper and magazine classifieds.

Ironically, these “cures” for opiate addiction almost universally contained opiates, unbeknownst to hopeful customers, who received little therapeutic benefit by today’s standards. But in an era before federal regulation of medicines and narcotics, there were no effective safeguards to protect addiction patients from medical fraud.

Much like Purdue Pharma, which famously marketed Oxycontin as non-addictive precipitating the opioid crisis, Gilded Age patent medicine companies also fraudulently marketed their addiction treatments as non-addictive, targeting and intentionally deceiving addicted customers. For their part, Gilded Age doctors were deeply skeptical of such products, and they often accused proprietors of fraud in medical journals and newspapers.

Samuel B. Collins of La Porte, Indiana, inventor of the “Painless Opium Antidote,” one of the era’s most popular brands, insisted that his product was not addictive. Collins was proven a fraud, however, by a skeptical Maine doctor, who in 1876 sent off a sample of Collins’ product to several chemists for analysis. Their tests indicated that the Painless Opium Antidote contained enough morphine to perpetuate opiate addiction, actually fueling demand for Collins’s product, rather than curing the underlying addiction.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, however, without any effective medical regulation or oversight, Collins maintained his fraud for decades. His business strategy presaged Purdue’s Project Tango by targeting vulnerable opiate-addicted individuals.

After decades of exposés by doctors and journalists, however, the opiate addiction cure trade collapsed during the Progressive Era under mounting public pressure and new federal legislation. One famous “muckraking” exposé, The Great American Fraud by the journalist Samuel Hopkins Adams, pulled back the curtain on the industry of opiate addiction cures for millions of appalled readers.

Hopkins painted such a scathing portrait of opiate addiction cures, whose proprietors the writer dismissed as “scavengers,” that the American Medical Association paid to disseminate Adams’s reporting as part of a lobbying campaign for the regulation of patent medicines. This strategy paid off. Although far from perfect solutions, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 regulated the ingredients and sale of patent medicines and narcotics, including opiate addiction medicines. These measures ultimately ensured that Collins, Keeley and other patent medicine sellers could no longer prey upon opiate-addicted customers.

Like its Gilded Age predecessors, today’s Big Pharma actively schemes to profit off of vulnerable, addicted customers, even while taking steps to ensure that opioid addiction persists. I believe that only sustained, vigilant oversight can prevent the reemergence of a medical Gilded Age, one in which companies like Purdue Pharma can manufacture an addiction crisis and charge customers for “curing” it.![]()

Jonathan S. Jones is a Ph.D. candidate in history at Binghamton University in New York.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

It is always fun to look into the drug use of the past and make direct comparisons to today. One of the problems with that is that addiction meant something different then than now; another is the assumption there was something we might call Big Pharma back then.

In the nineteenth century addiction was not framed as such a problem as today; in many jurisdictions opiates were readily available and so it did not require illegal activities to sustain a habit. Courtwright’s data looks at the shift of the users of opium, the changing demographic from a respectable middle class cohort using for medical purposes, to a criminal underclass using for fun; and argued that this is when opium prohibition became more of a national concern.

However, the assumption that addicted (or habituated) citizens were considered a huge problem over simplifies the case. Many docs did not see the habit as their concern—it was a personal failing, not a disease—while others were deeply concerned about habituation and the fact that it often was a result of their own prescriptions. (They saw this as a problem for the respectability of the profession). I have analyzed doctors’s records from the nineteenth century and found 25% of prescriptions included some kind of opium based pain killer. But that does not mean they were all addicts. They were, however, all people in pain.

At the same time, the shady vendors you reference (and everybody’s favourite images of patent medicines gone wild) were far from the Big Pharma we have today. The only real big pharma progenitors were mostly German (like Bayer), and they were manufacturing things like phenacetin, a nonopiated pain killer (later found to be carcinogenic) and Aspirin, which filled the anodyne demand and helped to interfere with an opiation of the nation. Bayer also introduced Heroin as a nonaddictive alternative to morphine or opium, and their mistake there was not about willful deception but about different assessment standards than we have today.

The big drug houses in North America like Parke Davis were mostly manufacturing standardized forms of popular preparations that you would normally go to your pharmacy to purchase on prescription. They were not synthesizing new drugs, as the Germans were doing. One notable quality assessment done by Canadian government chemists found these mass produced versions were much more accurately compounded than the ones you’d get from your local pharmacist. In other words they were safer and more reliable (results that seriously ticked off the emerging pharmaceutical profession). (Shameless plug I wrote a book on this).

So vilifying Big Pharma without nuance (which is often the result of the length limits of The Conversation as well I know) is tricky. There is much to learn today about the practices of the past, but I don’t think it is fair to say this is nothing new with Big Pharma. Big Pharma is a much different operation than 113 years ago when your FDA was formed. A better comparison might be with the robber baron rapacious capitalists of the time. Because to them, business and profit were foremost, but they framed it as a national imperative to allow companies to make as much money as they wanted with a little control as possible. And they profited wildly on the backs of their workers. Who then sought pain killers to deal with the effects.

And now that their fraud is coming out Purdu is threatening to declare bankruptcy to avoid having to pay for the clean up of the problems they created!

I agree with Carl (previous commenter).

I would also add that the structure of this article feeds into the alt-med stereotype/conspiracy theory world. I’m no apologist for bad actors. Yet articles like this, without a strong statement that supplements, remedies, etc. have NO requirement to demonstrate effectiveness OR even safety of the products being sold, risk pushing those without knowledge away from effective interventions and toward a land of magical treatments. Many people see Pharma as big bad impersonal corporations that only care for money and the supplement/alt med industry as caring individuals who want only the best for people. Neither of these is true.

We live in a capitalist system that attempts to drive innovation by rewarding those that create and bring to market new products. Being greedy, as abhorrent as it may be, is not a crime. Misrepresentation is another story. It seems clear that Purdue is guilty of this, and that the consequences have damaged and destroyed many, many lives. But the same is true for the many people (e.g. “Dr.” Oz, Joe Mercola, Andrew Wakefield, Gwyyneth Paltrow) who profit mightily by selling popularizing pseudoscience.

Cindy:

I went back and looked through the article and did not see *any* references to ‘alternative/herbal medicines are better than standard treatments,’ nor any references to buying products recommended by Gwyyneth Paltrow. It appears you went off an a tangent there. I think we need to stay on point in this issue, which is that many pharmaceutical companies are profiting from death and addiction, with very little regulation.

Good article, but you lost me at the conclusion when you stated ” … today’s Big Pharma actively schemes to profit off of vulnerable, addicted customers, even while taking steps to ensure that opioid addiction persists.” This is a damning statement that simply does not agree with my experience. Sure, there may be a few bad small players that willingly look the other way or view it as not their problem to address, but it is not a characteristic of “Big Pharma”. There are many, many companies making drugs, and to label the few, greedy, unethical ones as representative of an entire industry is simply misleading.

now vaccines, statins, dietary guidelines