Reading (and Understanding) Scientific Literature Isn’t Easy. Here’s a Guide to Help.

Reading scientific literature is not for the faint-hearted. It’s dense, and very often full of foreign terms and ideas.

VIEWPOINTS

Partner content, op-eds, and Undark editorials.

It also assumes a basic understanding of the discipline in question. I can’t imagine that many people outside the world of theoretical physics are reading journal articles on the subject. That makes sense: research has found that scientific literature across disciplines is getting more complicated.

But as more and more journals embrace the principles of open access, and more information becomes freely available online, curious readers are probably more likely to start engaging with scientific literature. That’s a good thing. Research shouldn’t be regarded as a closely kept secret for a small number of people. In a world full of half truths, simplistic and misleading summaries, and outright “fake news,” being able to read and engage with scientific literature can be a powerful weapon.

Of course, you can also seek out examples of scientists writing for the public. But be wary: not all scientists are willing to do this; we are, on the whole, very picky about details and don’t like generalizations. So try to engage with scientific literature where you can: it will be hard work in the beginning if you have no scientific background, but it’s a skill that can be developed.

So, if you’d like to start reading more scientific literature, here are a few tips to improve your experience. I’m focusing largely on the life sciences since that’s my area of expertise.

Science is about asking and answering questions. Scientific articles are the way in which scientists communicate their results to their peers. Here’s how to navigate those articles.

Choose journals that publish good science:

“Good science” is rigorous, verifiable and rooted in a broader body of research. There are however, an increasing number of scientific journals available. Some have better credentials than others; often, these are linked to reputable scientific societies. For instance, the South African Journal of Botany is the journal of the South African Association of Botanists.

Only people with a four-year degree who are active in the field can be members of the society. The same sort of rigour is applied to who can publish in the journal.

When journals aren’t linked to societies, you can look at their editors’ credentials. Reputable scientists are unlikely to allow their names to be linked to fraudulent or predatory (those that charge a fee to publish articles, without any review or editing) journals.

These are not reputable, and do not publish robust, good science.

Also, don’t be fooled by people’s titles. I would hope that no one would consult me about heart surgery but I sometimes see adverts where a “doctor” has endorsed a product — often one that has nothing to do with their field of expertise.

Start with the abstract for a broad overview:

It’s expensive to subscribe to most journals or to buy entire articles online. But even limited access journals usually supply the abstract for free. This summarizes the article and usually gives the major findings. You can then decide whether you want more details and are prepared to buy the article, if it’s not open access, or to keep reading if it is.

And then continue in a chronological fashion:

Most articles have an introduction which introduces the topic and sets the scene. It usually includes a statement as to the aim of the study — essentially, the question that the authors set out to answer. It also provides references to previous literature, which could be useful to understanding the topic. There will be references throughout the article; this is a way of ensuring that all statements are substantiated with reference to the published literature.

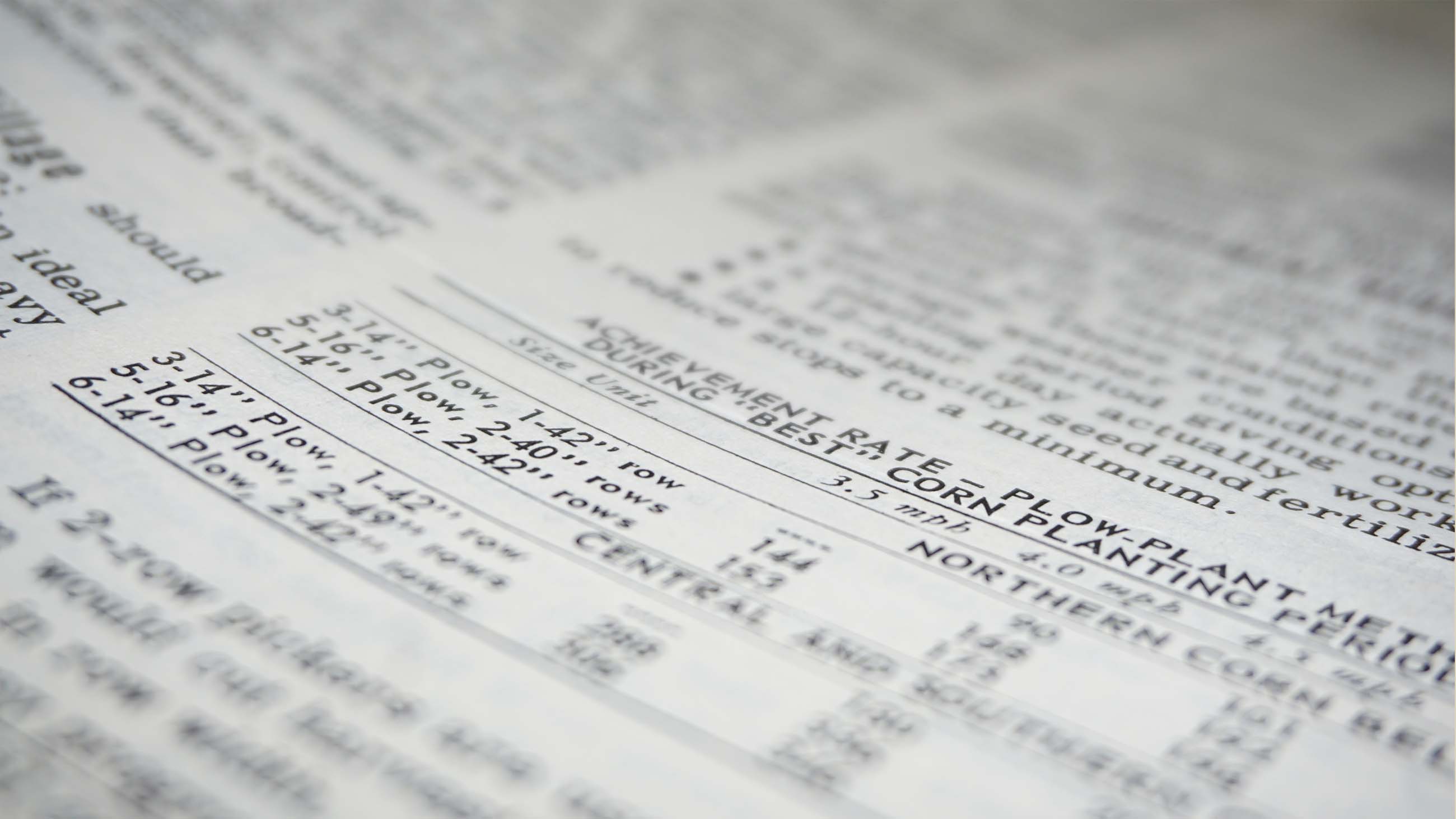

The next section of an article is usually followed by the materials and methods (although in some journals this might be relegated to the end of the article). Here, the authors will provide details about the methodology used in their experiments. This is where things can get very technical, but you will also see constant reference to other research that has been published using the same or similar methods if you want to get a better understanding of the methods.

Then comes the results section, which outlines the results yielded by the experiments. This, too, is likely to be very technical but is also where the details are provided.

The last section is the discussion, which provides the authors’ interpretation of the results. This is often what scientists read most carefully, since it’s where the authors “connect the dots”; they are also likely to provide a conclusion and suggest an answer to the question they were trying to answer.

Once you’re finished reading one article on a topic, read some more. You should not ever just believe what is stated in a single article. Science is very repetitive and builds on the research that has come before, so researchers are often repeating others’ experiments. This is where the in text references come in handy. They provide a way for results from one laboratory to be checked and tested by others. So, to get the truth about a topic, read a number of articles about it.![]()

Brenda Wingfield is vice president of the Academy of Science of South Africa and DST-NRF SARChI chair in Fungal Genomics at the University of Pretoria.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.