‘Are We Rome?” asked the author Cullen Murphy a decade ago, in a provocatively titled book that compared the 21st-century United States with the final days of the Roman Empire. Lately there’s been no shortage of Cassandras who emphatically answer yes.

BOOK REVIEW — “The Fate of Rome: Climate, Disease, and the End of an Empire,” by Kyle Harper (Princeton University Press, 440 pages).

“The speed with which we’re recapitulating the decline and fall of Rome is impressive,” opined the conservative commentator Bill Kristol, in a tweet this past July, taking issue with President Trump’s treatment of the press. “What took Rome centuries we’re achieving in months.” And the Cornell historian Barry Strauss bemoaned the parallels between alleged American failings and those of ancients in an online column for Fox News in October 2016: “Just think about what Rome had and what we have. Morals out of a bacchanalia? Check. Abuse of public office for private purposes? Check … Oh the times, oh the customs! Where is Cicero when we need him?”

Such comparisons are almost invariably political — pundits projecting onto the Roman story the particular modern grievances that most trouble them. But in the new book “The Fate of Rome,” Kyle Harper suggests that they overlook the big picture. Sure, the empire had internal problems — vicious leaders here and there, political coups, the disproportionate influence of moneyed elites, and trouble maintaining its far-flung borders. But Harper, a historian at the University of Oklahoma, has assembled compelling evidence that Rome died mainly from natural causes: pandemic diseases and a temperamental climate. If Americans want to compare our country’s faults to those of Rome, they might more closely scrutinize our biological and environmental vulnerabilities than our institutions alone.

Throughout the book, Harper positions nature as one character in a centuries-long drama. At the empire’s peak, the human actors — the political, cultural, economic, and military leaders who set up its institutions — were more than equal to the task. Under Marcus Aurelius, emperor from A.D. 161 to 180, about a quarter of humanity lived under Roman rules and influence. The Roman population swelled, wages rose, cities flowered (at its peak, the city of Rome had perhaps a million inhabitants), and vast trade networks threaded across Africa and into Asia.

But at the time, it was easy for Rome to make successful moves: Nature dealt it an especially good hand. During much of the Roman Climate Optimum (about 250 B.C. to A.D. 150), the empire was blessed with stable weather, abundant rain, and warm temperatures. Romans grew and shipped prodigious quantities of grain, especially in North Africa, and their leaders sometimes went to great lengths to hold wheat prices down, offer subsidies, and make sure citizens could feed themselves.

Then, from the middle of the second century onward, nature began dealing out some rotten hands — in the form of natural disasters and vicious germs — and the empire couldn’t hold its winning streak.

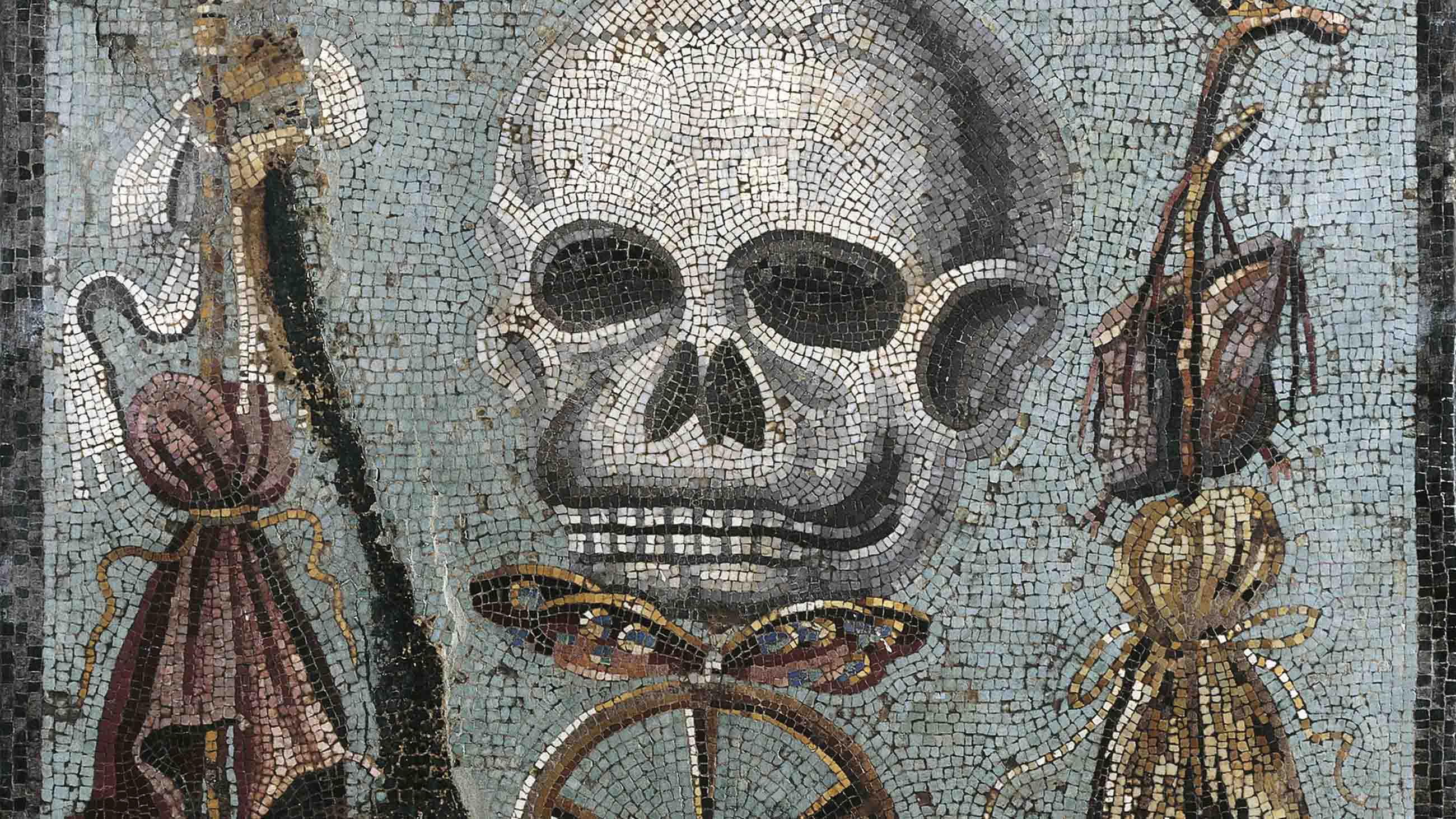

The germs were the most violent and obvious destabilizing forces. For all of the society’s technological sophistication, Roman doctors had no notion of germ theory, and Roman cities hosted a robust resident population of waterborne and airborne diseases —especially malaria, typhoid, and various intestinal ills.

On top of this, the empire’s densely urbanized populations — connected by intricate trade routes — were excellent targets for major pandemics. Harper demonstrates that the Roman Empire was hit by at least three great plagues, each a powerful blow to both its population and civic institutions. During one wave of the second-century Antonine plague, which was likely a form of smallpox, as many as 2,000 people died every day. A century later, a disease that sounds, from accounts written during that era, a lot like hemorrhagic fever (the gruesome Ebola family of diseases) migrated from Ethiopia across the rest of the empire and took a similar toll.

Meanwhile, the climate grew more and more erratic. “In winter there is not such an abundance of rains to nourish the seeds,” wrote Cyprian, an early Christian writer of Carthage. “The summer sun burns less bright over the fields of grain. The temperance of spring is no longer for rejoicing, and the ripening fruit does not hang from autumn trees.”

Drought struck the empire’s breadbasket of North Africa. The combination sent the society reeling, but it was able to recover until the climate swung again. In the fourth century, when the Eurasian steppe also fell under drought, nomadic peoples like the Visigoths and Huns (whom Harper describes as “armed climate refugees on horseback”) began to antagonize and terrorize Roman territories in Europe. Famously, the Visigoth leader Alaric sacked Rome in 410, effectively sounding the death knell of the Western part of the Roman Empire, which eventually fragmented into small, feudal territories.

The empire’s smaller eastern version, a.k.a. the Byzantine Empire, fared relatively well through the early years of Justinian, emperor from 527 to 565. Justinian — who came from a family of commoners and married a former actress and prostitute — led the empire with a style about as brash and contentious as today’s politicians. But he was also a man of action. “He was loved and loathed,” Harper writes, as he clashed with political elites, altered the tax code, and launched a massive program of government-sponsored engineering projects, with a special focus on flood control and aqueduct repair.

But by 541, the third and most gruesome of Rome’s germ invaders arrived in the Mediterranean — the Black Death, bubonic plague. The disease broke out as many as eight times between 542 and 747, and raged across the empire, carried by fleas riding on the bodies of rats. Wherever plague arrived, it killed about half to 60 percent of the population. As if that weren’t enough, the Mediterranean region suffered through a period of floods, unproductive cold summers, and dismal frigid winters now known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age. It’s hard to imagine any civic institutions that could withstand that kind of mortality and disaster.

Historians have long neglected the role of these actors — germs and climate — in bringing down Rome, partly because the evidence was simply unavailable. “Most histories of Rome’s fall have been built on the giant, tacit assumption that the environment was a stable, inert backdrop to the story,” writes Harper.

Some of the most interesting passages in “The Fate of Rome” describe how historians are now partnering with researchers in genetics, archaeology, and climatology to open up whole new avenues of inquiry into the past. Advances in DNA sequencing have made it possible to verify the presence of bubonic plague in ancient graves, for instance, and more definitively document some of its whereabouts in antiquity. Meanwhile, new research in historical climatology has painted more detailed pictures of Roman-era climates.

In the end, if Harper is correct, the story of Rome and its climate and germs is more deterministic than hopeful. American society does resemble Rome, but in even more alarming ways than we previously understood. Though modern health care systems give us a formidable advantage in the fight against disease, our hyperconnected globalized society is still an excellent medium for transmitting powerful germs. The next H1N1 or Ebola outbreak could have a far more calamitous outcome than those of the recent past.

Meanwhile, we’re at the precipice of a rapidly destabilizing climate, this time thrown off kilter by the same energy sources — fossil fuels — that helped create our prosperous modern global institutions. The two phenomena are connected, since the warming climate may be expanding the range of some diseases, including Lyme, malaria, Zika, and West Nile virus. Still, we know far more about both the causes of climate change and the ecology of germs than our ancient ancestors did. Perhaps we have a fighting chance of avoiding Rome’s fate, if we heed the true lessons of its fall.

Madeline Ostrander is a freelance science journalist based in Seattle. She has written on climate change for Undark, and her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Audubon, and The Nation, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Read with a voice? Yes/No.

Wait, you mean dramatic changes in climate existed before humans started burning fossil fuels on a massive scale? Whodathunk?

Climate scientists, for one. They’re the reason we actually know what climate was like at this time.

Here’s a fairly comprehensive debunking of the tired insinuation that past changes in climate somehow debunks anthropogenic global warming: https://skepticalscience.com/climate-change-little-ice-age-medieval-warm-period-intermediate.htm

The book was poorly organized. It had factual errors that no competent modern historian would make, and several errors that no linguistic classicist should make. Many charts were inadequately labeled. Footnotes were sloppy. It failed to integrate non-disease, non-climate history well enough to allow assessing the relative importance of disease and climate to the health of the empire. It failed even to allude to the historic role of plagues and climate in important predecessor and neighbor cultures. What a wasted opportunity!

BTW, anyone who imagines Justinian to have been anything other than a lousy emperor really should read Procopius.

Your argument about ancient Rome is reasonable and in line with Jared Diamonds theories on the effects of germs and climate, which is the best scientific theory of cultural development available. However, unlike Rome, we know with increasing accuracy the mechanisms of global biological threats and the effects on climate of increasing atmospheric CO2. We have remedies for both, and epidemics on historical scales have not materialized for over a century. Biological and nuclear weapons are much more of a threat. Your argument about the relation between climate change and disease risk, not associated with disruption of food supply, is exceedingly weak.

Seems like thin beer to me. I’d say the barbarian invasions had a thing or two to do with the fall. And didn’t the subsequent barbarian kingdoms in the West thrive?

And did not Alaric and his successors also deal with cold and disease, yet won out.

“Now that I know about confirmation bias, I see it everywhere!” (Clearly label as satire.)

The author makes good arguments in the same genre as “Guns, Steel and Germs” and “The Silk Roads”. Like the Romans, there is a lot of finger pointing and avoiding personal responsibilities for what will unavoidably be, a precarious future. There has always been a precarious future – there are no tablets on which humankind is guaranteed stable climate, freedom from disease, or unending resources. We will as likely face 100 years of unparalleled prosperity as 100 years of unparalleled disasters – every prophet forecasting either extreme has been proven wrong time and again. We can, however, be prudent in our actions and limit the excesses of extravagant spending and thoughtless exploitation of resources.

From the Amazon web page on this work, “A sweeping new history of how climate change and disease HELPED bring down the Roman Empire”. There were many causes of the disintegration of the Western Empire and the truncation of the Eastern Empire all of which contributed to this ancient upheaval, not just one. Believe the reviewer has an agenda and is attempting to sway opinion to hers. Publication data (omitted from the review:

Series: The Princeton History of the Ancient World

Hardcover: 440 pages

Publisher: Princeton University Press (October 24, 2017)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0691166838

ISBN-13: 978-0691166834

Bad analogies. If we lived in the relatively primitive Roman times, you might have a point but we don’t. The ideas that we will suffer pre-modern scale pandemics or wide-spread severe famines are a bit of a stretch. Hyperbole is far too commonly used in the media today. We all should learn to be a little more accurate in our thinking to avoid this kind of junk.

Your article mentions climate change. The later Roman Empire experienced a COOLING climate, NOT a WARMING climate.

Note that the EASTERN Roman Empire did NOT collapse.

The means to study past climate cycles and the effect on human history is a fascinating development as we gather more data from ice cores, sediment cores, and the pages of history. Extraordinary events such as volcanoes, earthquakes, tsunamis, celestial cycles, and bolide impacts are being discovered as well. The Roman, Peruvian, Mayan, Chinese, and other cultures were all struck by extreme climatological disasters.

I read that around 1187 B.C. several eastern Mediterranean cultures experienced rapid declines that have yet to be adequately explained.

One can only speculate on the disasters faced by human cultures with the climatological disasters at the end of the Younger Dryas period (12,800 years ago) when mile high glaciers at New York latitudes melted and sea levels rose 400 feet (120 meters). Most coastal and riverine based cultures would have been devastasted.

The Roman Empire fell because it

ceased having a unified culture and

identity due to an amalgamation

many other cultures and races with

their respective values and beliefs.

Too much too fast. So called” climate

change” had little to do with it.

Droughts and plagues occurred at

other times previously and it did not

bring down the Republic or the Empire.

The fall o Rome lead to the so called

dark ages. The light went out.

Beware uncontrolled immigration

America!

The fall of Rome did not lead to the Dark Ages. The ascent of Christianity in Western Europe and its zealous adherents led to the Dark Ages due to active destruction or neglect of pre-Christian knowledge. No such age exists in the history of the Eastern Empire or the Caliphate.

Which presumes one definition of Christianity, and not that of the definitive source of that title, while others disagree: “As much as it suits the agenda of some clumsy anti-Christian zealots to claim that Christianity caused the “Dark Ages” it’s an attack based on a weak grasp of history.” – https://www.quora.com/Did-Christianity-cause-the-Dark-Ages-i-e-the-5th-to-the-15th-centuries

Funny I must have missed where the climate change resulting from the carbon based ‘pollution’ caused by the Empire’s bustling industrial emissions and automobile’s burning fossil fuels caused their decline…. oh wait.

Very interesting! I see you’ve gotten some nasty blowback from at least one defender of the sacred cows of Roman historiography. You must be on to something! I love the way real science is being used to re-examine our understanding of the past. There’s nothing like having the facts when seeking the truth.

Ahm no, Rome didn’t fall due to climate change or disease. Rome fell for many reasons, but the biggest and most important of it were internal strife, lack of cultural identity (Romans didn’t want to serve in military anymore, and military was primarily composed of barbarians, without good discipline, over spending, and inability to develop sustainable economy.

You are trying to make a very tortured point without obviously understanding Roman History.

The biggest weakness of Rome was it’s Large Government and lack of good succession. Augustus tried to create a stable system, and did for a bit, but ultimately Principate had a huge weakness as it was based on military rule. This ultimately meant that leaders needed to pay off military and be in effect strong man. There is very good reason why it didn’t take even a century for the year of 4 emperors to happen. In addition to the fact that after Augustus you had Tiberious who was seriously flawed, then Caligula (you maybe familiar with him?), Cladius, and Nero.

This was why Rome fell not your tortured and silly argument.

Marek – did you even read this?

Your rebuttal does not address any of the points raised in this piece. I would like to see you make an attempt at a counter argument rather than simply restating the currently accepted historical theory.

I think you may find that these are not mutually exclusive.

Ahm no. It’s quite a well written review of what is no doubt quite a well written book. Couldn’t make much sense of what you wrote but did note the term “large government”, which is quite revealing as to how you prefer your ‘history’.

Rome’s reach grew until Marcus Aurelius. At that point, Germanic tribes were partially incorporated into the empire. There were times of ebb and flow, but disintegration occurred slowly after MA’s reign. The western empire’s capital moved from Rome to Ravenna starting in 402 AD, with Rome too difficult to defend. Internal disputes between west and eastern leaders led and poor local leadership was the primary source of downfall.

The last great Roman general, Flavius Aetius led a coalition of Visigoths, French and Germanic tribes against a superior force of Huns led by Attila in 451. Aetius was generally credited with stabilizing the west during his 20 years as military commander. The western “Emperor” had Aetius killed in court in 454; the emperor Valentinian was in turn assassinated as his guards stood by 6 months later. Then the Huns invaded northern Italy unopposed. So I would venture that internal politics had a greater impact on the end of the western empire than plague.

I would suggest that the USA can not fix anything and that previous leaders(some presidential) have not headed history either. Climate and nature don’t destroy moral values, we do! Think about and apply that to what the article says about us as a society.

The missing part is, as always, energy. Back in Roman times most energy was coming from grain. Nowadays it’s mostly coming from fossil fuels. Working on energy availability is a much stronger and direct predictor of economic turmoil than climate.

Have somebody read this to the sitting president and smack him silly over cutting financial medical/health aid for overseas nations. As long as aircraft fly around the world, these dollars are well spent to stop Ebola, etc., from killing off US populations.

Oh right, we have to keep paying for, what, everything? We pay for Europe’s defense. We pay for east Asia’s defense. And we have to pay for the good health of third world countries? Please.