An Opioid Antidote Gains Crucial Support

It took a national epidemic — and one that disproportionately affects rural whites rather than people of color and city dwellers. But the tide of U.S. policy is shifting toward more effective prevention of drug overdoses from opioids.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. death rate from overdoses of heroin and opioid pain relievers increased 200 percent from 2000 to 2014, and more than 33,000 deaths in 2015 involved opioids.

State laws and federal policy regarding prescriptions may curb the problem. But overdoses are likely to persist even if prescribers and pharmacies operate under the most cautious guidelines. Some overdoses occur among people who become dependent on or addicted to opioids legitimately prescribed to control pain. People who take prescription opioids along with other medication can suffer deadly consequences from drug combinations. And illicit sales of heroin and other narcotics are unlikely to be contained.

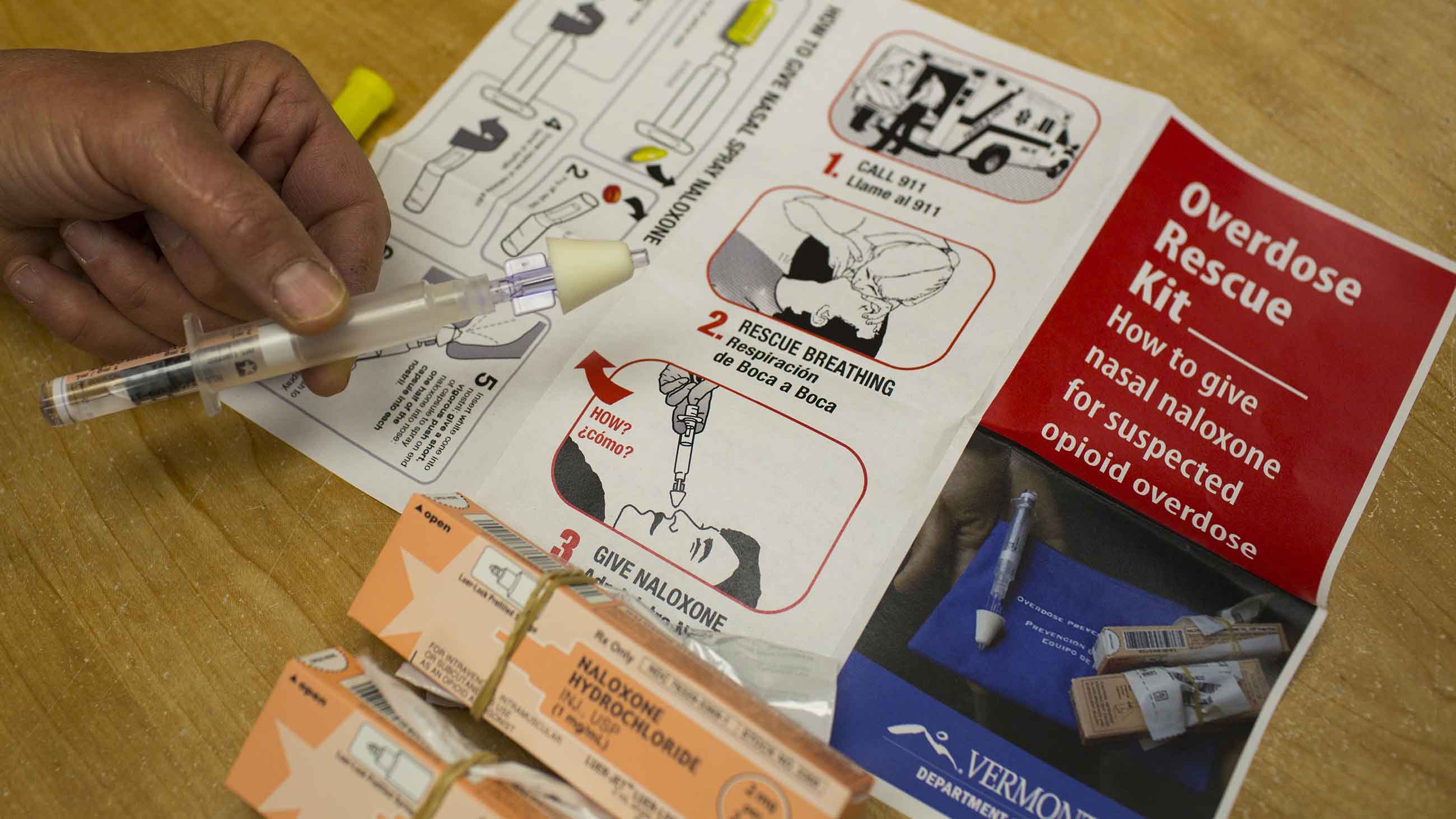

Many physicians and community health providers now advocate a multipronged solution to overdoses, including easier access to the pharmaceutical drug naloxone, which reverses the effects of heroin and prescription opioids. The drug is fast-acting and has few side effects. Paramedics and emergency-room staffers have used naloxone to save lives for decades. And some harm reduction centers and police departments have distributed the drug. Naloxone-equipped police reduced opioid overdose deaths in Lorain County, Ohio, according to a study published in 2015. But the remedy remains out of reach to many people who don’t make it to an emergency room in time.

In the past 15 years, efforts have helped make the drug more accessible. Laws in 31 states now protect laypeople from criminal liability — and in 39 states from civil liability — if they give naloxone to someone who has overdosed, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. New Mexico was the first U.S. state to take such measures. On Monday, Missouri’s House of Representatives approved a similar law.

New Mexico has now taken another progressive, scientifically grounded measure that puts it ahead of the pack. A law signed last week by Gov. Susana Martinez aims to make the drug more accessible to some of those at highest risk for overdoses. The legislation will require state and local law enforcement officers to carry “rescue kits” containing two doses of naloxone, along with information about the signs of an opioid overdose and how to best administer the drug. The law, set to go into effect July 1, also requires corrections facilities to provide the kits to inmates who are about to be released and who have a history of opioid problems.

In rural and underserved areas, where most New Mexicans live, police officers, rather than EMTs, are often the first to respond to a 911 call. New Mexico has long had one of the nation’s highest rates of death from drug overdoses, mainly prescription drugs.

A few studies have revealed a significantly higher risk of opioid overdose among former inmates during their first weeks after discharge, compared with their drug-using peers in the community. So former inmates will be required to receive a prescription for naloxone. The same set of materials will go to patients in federally certified clinics that treat addicts with narcotic replacements, such as methadone or buprenorphine, under the new law.

Joanna Katzman, a neurologist and director of the University of New Mexico Pain Center was instrumental in developing the legislation. She and her colleagues have observed that people provided with naloxone doses often use them to rescue other people. For the past year at the university’s Addiction Clinic, overdose education and naloxone were given to more than 350 patients receiving treatment for drug addiction. “Since then, 89 overdose reversals have been recorded,” she says. “Only one of the people who had a reversal was from the clinic. It’s the patients from the clinic who saved other people’s lives.”

Katzman and her colleagues are encouraged by this new policy. She notes that some evidence shows people who recover from an overdose after receiving naloxone tend to seek further treatment for addiction. As needle exchange activists said in the 1990s, dead addicts don’t recover.