In Upstate New York, Leather’s Long Shadow

It was as if a meteor had struck the tanning industry. For more than a century, leather production had been the great engine that powered the regional economy of upstate New York. And then, almost overnight, it seemed, the tanneries were gone, as one shop after another fell in the 1980s to global competition and strict new environmental regulations. Gloversville — once the glove-making capital of the world — sank into a deep depression, perilously close to extinction itself.

In the decades since, the survivors of the cataclysm have struggled to clean up and rebuild. True to form, in commerce as in nature, small mammals emerged on a landscape devoid of dinosaurs, and today, at least a few of them are thriving.

“I don’t think anyone is looking to bring back the tanning industry,” says Gloversville Mayor Dayton King. “But Gloversville and Fulton County are definitely coming back.”

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

The story of Gloversville is the story of small manufacturing communities across America, dealt near-fatal blows by the offshoring of jobs to markets in developing nations with cheap labor and lax environmental controls. Ironically, just as some American manufacturing regions are staging modest comebacks, those early offshore markets are facing their own Gloversville moments, squeezed by competition from other countries and growing environmental regulation at home.

The Hazaribagh district of Dhaka, where about 90 percent of Bangladesh’s leather is produced, is a prime example. Like their Gloversville counterparts decades ago, Hazaribagh tanners face growing competition and government orders to stop polluting local waterways or cease operations entirely. How long that transition might take is an open question, but once the tanneries are gone from Hazaribagh, the Bangladeshi government will have a monumental cleanup — far worse, to be sure, but not so different from what federal and state authorities found in New York. The parallels between Gloversville then and Hazaribagh now are more than ironic or coincidental; they are instructive.

“Growing up in a leather town was exciting. We were the leather capital of the world,” says Mark Kilmer, president and CEO of the Fulton Montgomery County Regional Chamber of Commerce. “The survivors of the business have had to think out of the box and reinvent themselves and become more specialized.”

At the dawn of the 20th century, Gloversville — named for its glove-making industry — was said to have more millionaires per capita than any other city in America. Whether that is truth or legend, one thing is certain: tanning and glove making made many families very wealthy and employed the vast majority of the town’s work force. About 90 percent of the gloves sold in America between 1880 and 1950 were made in Gloversville, which by some estimates had more than 100 leather and glove companies at its peak.

The tanneries turned out supple leather for glove makers, and back in the day before the Environmental Protection Agency, they pumped their wastes, chemicals, and filthy water straight into Cayadutta Creek at the rate of 2 million gallons a day. Stories abound of the river changing color with the dyes and foaming up into sudsy crests 10 feet high.

A young Neil Sheehan described the Cayadutta in a 1964 New York Times article as “thoroughly poisoned with sewage and household detergents and with animal grease, flesh, hair, dyes, and chemicals from its tanneries.” Sheehan’s reportage, seen through the lens of history, is eerily prescient. He tagged Gloversville as “an example of the man-made water pollution” that the state’s $1.7 billion Pure Water Program was designed to combat, and lamented that but for the contamination, a drought-stricken upstate New York would have plenty of water to drink.

The final blow for Gloversville’s tanneries came with the federal Clean Water Act of 1972 and subsequent state and local laws that ultimately required industries to have their own effluent treatment systems. Most tanners, already losing business to cheaper suppliers overseas, saw no reason to spend a million dollars or more for a wastewater treatment system. Others borrowed heavily to finance the equipment, only to bleed out slowly.

“That was pretty much the definitive line in the history of tanning in the county,” says Matthew Smrtic, owner of both Sunderland Leathers, a leather buyer, and the Colonial Tanning Corporation, one of the county’s few remaining tanneries.

Gloversville lost more than a third of its residents, shrinking from a peak population of 23,634 at the 1950 Census to just 15,665 people in 2010. The glove-making industry was the first to go, its business siphoned off by factories in Asia. The tanneries followed, and by the 1990s unemployment was as high as 13.5 percent. The official unemployment rate has come down to an average of 5.7 percent in 2016. But locals say the rate doesn’t tell the whole story; many people have aged out of the workforce or stopped looking for jobs. About 24 percent of the town’s families were living in poverty in 2010, according to New York state demographic data.

Smrtic’s father-in-law, a longtime Gloversville tanner, was one of the survivors. He installed treatment systems, scaled back during the hard times that followed, and kept operating the tannery, which Smrtic and his wife now own. Smrtic weathered choppy economies in the 1990s and early 2000s by identifying and successfully exploiting a niche market for high-quality American deer and bison skins. Sunderland Leather buys raw deer and bison hides, sends the skins to Colonial for tanning and coloring, and then sorts the tanned leather for sale to luxury goods manufacturers, mostly in Italy and China.

“You have to have a specialty,” Smrtic says. “The commodity stuff comes out of China or Vietnam or wherever the next low-wage, low-regulation place is.”

The common denominator for Gloversville’s remaining tanners, leather finishers, and glove makers is quality custom work. Townsend Leather in nearby Johnstown produces performance aircraft upholstery leather. Daniel Hannis, president of Adjon Inc., handles sheep and goat skins, sending the raw hides to Colonial for tanning and selling the finished leather for high-end fashion and military gloves. Brent Heroth, who opened Brooklynn Custom Leather Works about a year ago, paints and stamps patterns into leather for furniture makers and interior designers.

“I was a little kid when the industry was strong, and I’ve seen it take a dive,” Heroth says. “I keep doing the small things that the bigger places don’t want to be bothered with. People are looking for custom and quality, and I can give them that.”

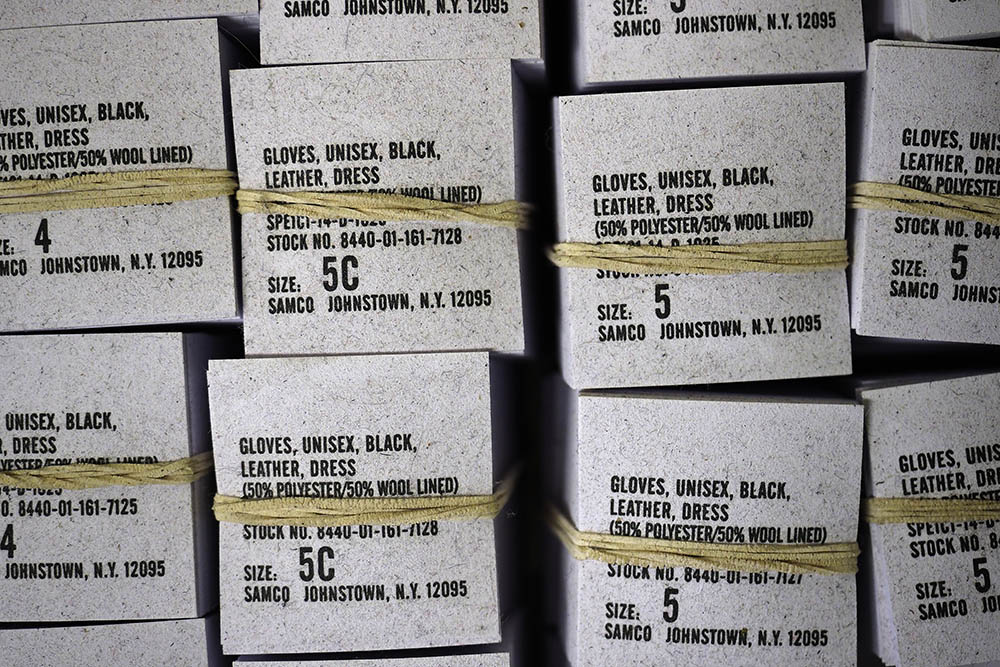

Samco, one of Gloversville’s last remaining glove companies, makes leather dress gloves for the U.S. military, turning out more than 100,000 pairs a year, by hand, on traditional sewing machines. The company’s co-owner, Richard Warner, went to work in the glove business straight out of high school in 1979. He was hired as superintendent at Samco in 1996 when its owners, Salvatore and Ila Greco, decided to expand. At its peak, Samco employed 75 people but now is down to 35, largely because sewing machine operators are hard to find, Warner says.

“The only thing that has saved us is that clothing for the military has to be made in the USA,” Warner said. “Otherwise, we wouldn’t be here.”

Glove making was always considered the upper-crust industry in town. Men wore white shirts and ties to work in the glove factories, in sharp contrast to the tanners who returned home at night reeking of animal hides and chemicals. The money was better too, allowing many families to send their children to college. City Councilman Vincent DeSantis grew up in a family of glove makers and came home from college each summer to work in a tannery, his father’s way of encouraging him to finish his degree.

“The tanners worked very hard physically in very rough conditions,” DeSantis says. “Sometimes when you’d walk past a tannery or in the neighborhood of a tannery, you could smell that smell of unfinished leather and the smell of tanning.” The dirty tanning of old killed the fish in Cayadutta Creek and left Fulton County with more than two dozen abandoned and contaminated industrial locations designated for cleanup as federal Superfund or brownfield sites. Several still await remediation.

“They said our city smelled so bad because of all the chemicals, but nobody complained because everybody had money,” says Mayor King.

Then, in 1989, as tanneries continued to shutter, a report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sent ripples of fear through the community. The CDC reported that tanners on the finishing line who used the solvent dimethlyformamide (DMF) could be at increased risk of testicular cancer. The CDC based its findings, in part, on three cases of testicular cancer diagnosed in workers at a Gloversville tannery. Fulton County medical records added another seven cases to the total. Half of the cancer patients had worked in tanneries. The New York Times reported at the time that the tannery in question had stopped using DMF dyes, as had other nearby facilities, but that did little to assuage anxiety.

Fulton County Sheriff Richard Giardino, who grew up in Gloversville, said he had friends with testicular cancer who had worked in the tanneries or leather shops. “It was definitely a concern,” he said. “Everybody thought that was where it came from.”

Today, leather processing in the United States is highly regulated. Smrtic’s Colonial tannery workers wear protective equipment, masks, and gloves and most of all, manage the chromium solution carefully to ensure that the chemicals are fully absorbed by the leather and not wasted in the bath. The tannery uses a multistage process to treat its effluent, separating solids, removing sulfides in a contact tank, adjusting the pH balance, filtering and clarifying (twice), and testing the water before discharging it into the closely monitored municipal wastewater system. Even Heroth’s small shop has to have a monitored wastewater permit.

The Cayadutta Creek now is a sparkling trout stream and with the Mohawk River (also much improved) provides abundant water for Fulton County’s growing dairy-products and food industry. Fage USA, a maker of Greek yogurt, and Euphrates, a feta cheese company, opened plants, attracted in part by the extensive water and sewer infrastructure built originally for the tannery industry. Pata Negra, a Spanish cured meat company, is making chorizo in Gloversville.

A Walmart distribution center in Johnstown and a Target distribution center in neighboring Montgomery County have brought jobs to the area. The county is also wooing internet businesses and light industry, touting affordable housing, beautiful scenery in the foothills of the Adirondacks, proximity to New York City and shovel-ready sites.

Gloversville has an ambitious downtown redevelopment plan that calls for renovating the city’s grand old buildings and revitalizing nearby homes to create a vibrant community where residents can walk to shops and restaurants. The Mohawk Harvest Cooperative Market has opened in Memorial Hall, an opera house built in 1881, and DeSantis expects more businesses to follow.

“I saw Gloversville when it was really booming and everybody was working,” says DeSantis. “Then I went away to school and to the Army and came back to practice law in 1978. And Gloversville was declining and really kind of bottoming out in the 90s. It’s been in a funk. And now, to see Gloversville bootstrapping itself up in the 21st century, well, that’s an exciting thing.”

Funding for this project was provided in part by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Larry C. Price contributed reporting for this story.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

What about the Cancer from the chemicals used.My Mother lived on Wilson street in the Mid 1920’s…IN THE 1960’S I would visit my grandparents the smell was horrific..Sepage from containers in the building would be all over the grass and streets!

Some efforts have been made to clean the area up (environmentally). Sadly the area is still highly contaminated. I grew up in the middle of gloversville as a child / preteen. During that time my father always had a vegetable garden as did several neighbors. My father stopped gardening the year he purchased a rototiller from sears on Fulton st. After mechanically tiling the garden he kept since I was born, he discovered massive amounts of leather under the soil. All of the neighbors that were adult age when I lived on that street have died of cancer. This was Montgomery Street.

My parents decided to move out of the city and build a new home in a “healthier area”. The area they chose was farmlands, away from the tanneries and chemicals. Well with a dairy farm down the road and miles outside the city who would have thought we would later discover the wells were contaminated by a city landfill miles away. The city was forced (they didn’t want to) extend city water to residents. In my early 20’s I watched a beautiful young girl die of cancer. Coincidentally or not, her parents water well was one of the epa monitoring wells. It had some of the highest readings of voc’s In the water. It was also the furthest monitoring well from the landfill. Unfortunately this is as far as the city water was/ is extended. Neighbors 30ft away from where this beautiful young girl died are still drinking well water. Dec has closed the case and haven’t done any further monitoring since 1996. Several people have now gotten cancer a short distance past the areas with city water. A coincidence? I don’t know. The street my family moved to trying to escape from the contamination of the city – Bemis Road. I guess that plan didn’t go so well. I believe the contamination has spread to 349 and also Warren Rd. Where stupidly I decided to settle as an adult. I guess my fate was sealed long ago!

I graduated from Gloversville High in 1954 and I believe that there was a glove making school in a separate building next to the Sr. High School. I had heard that it taught glove making from the bottom up. Does anyone know how long that vocational school was in existence?

Great Article! Born and raised in Gloversville. I don’t think anyone who lived there wan’t involved in some way or another with the industry. I remember the smell and the many colors of the Creek very well. And contrary to what was said in the article, not everyone had money. We lived and grew up in the area because that’s were our family had been for a hundred or more years and many still do live there. Thank you again.

I grew up in Gloversville, and had a grandfather, father and two uncles in the glove business. I graduated from GHS in 1951. Went away to college and then the Korean War, coming back to visit a few times, but everyone is gone now except for one elderly aunt and one cousin.

After spending my entire adult life as a technology writer and editor, I have finally retired and am now writing my memoirs and Gloversville is an important part of my story.

Please post my email address. I will gladly correspond with anyone from Fulton County.

[email protected]

My Julien and Jeannisson ancestors came from Millau, France (France’s “Gloversville”) My Hodder and Jenner ancestors came from Yeovil, England (England’s “Gloversville”) Several generations worked in the Fulton County glove industry. My Jenner/Julien great grandparents were the last in the industry and lived next door to Salvatore “Sammy” and Ila Greco.

Awesome article – very well done! I grew up partially in Gloversville and Broadalbin. I remember plenty of older women that sewed gloves in their homes. This job and industry loss is not limited to the glove and leather industries. Look up and down the Mohawk Valley – GE, Coleco, Rug manufacturers, White Mop Wringer and hundreds of other manufacturing plants have gone and their good paying single paycheck households with them. Now families need 2, 3 or 4 paychecks to make the same money. A great treatise on this economic decline is “Men Without Work” by Nicholas Eberstadt. No political party or President in the last 40 years had any idea how to cope with this job loss. Automation, globalization, and regulation all contributed but there never was nor is there now a plan to bring relief to the minimum wage earners, seasonal and temporary employment. Willy Nilly, here we go. Consider the late writer and social critic Kurt Vonnegut observation, “I’ll tell you…one thing that no Cabinet has ever had is a Secretary of the Future, and there are no plans at all for my grandchildren and my great grandchildren.”

In the early 1950’s, my father owned a handbag factory, Kervita, located at 11-13 Cayudutta street, the backside and small parking lot bordering the Creek. I used to visit there while in high school, and was always amazed by the different colors exhibited by the rushing waters from week to week. In those days, Gloversville was a wonderful place to live. But sadly, a number of my classmates have fallen to cancer, perhaps relating to the badly contaminated Creek.

Hi Jerry, Great article. Does everyone love their hometown as much as I do? Glad to be in touch with you!

Jackie & Larry Smith: WE both grew up in Gloversville. We played on the shores of the Cayadutta Creek when we were kids. We lived upstream of the first leather factory. At that place the creek was crystal clear – not so further downstream. Jackie’s Grand-father, Dad and both brothers worked in the leather mills at some point in their lives. My mom worked at St.Thomas making wallets and she also worked at Allegro sewing shoes. We have wonderful memories of growing up in this small town.

I grew up in the south end of Gloversville and went to Lexington school and then 5th and 6th grade in the “new” Park Terrace school. We had to cross the bridge over the Cayudetta Creek on hill street. Usually we would have to hold our nose in crossing because of the stench. On the way to school the creek might be brown and perhaps red on the way home. But the city was a vibrant place to grow up. Friday nights, pay day, in downtown Gloversville was an event. Traffic jams at the 4 corners with people shopping and socializing. Ahh the good old days, maybe!!

My father ran Milligan & Higgins and was part of the group that built Omnicology (the fertilizer plant) at the industrial park in Gloversville. I had great memories growing up there as i worked summers in Kargs & the glue factory It is a shame what happened to the great little town in the Adirondacks but greed and ignorance was it’s downfall. Very good article but you should point out that there were many large corporations that owned most of the tanning operations. The big one was Karg/Fuerer who own quit a few of the problem locations. Anyone remember the deaths of the poor men who went into the sewer to clean a clog and dies from the fumes of the chemicals down there. That was at Karg and was the start of the end as the EPA really clamped down after that. I remember the hoops my dad had to jump through to meet their demands and what was once a thriving multi million dollar business lost all it’s ground and after that most of the animal hide glue was made overseas. The glue factory sold to the US Mint (for stamps), 3M for masking tapes etc, Norton for sandpaper, and Atlas for matches.

True, the decline of the leather business played a part in the demise of Gloversville. But it wasn’t the regulations and foreign competition that killed the city. Yes, the industry, not the city. A bigger factor was the owners of these factories keeping different industries from entering the county. For nothing more than not wanting to have to “compete” for the work force out there. Competition there would have meant having to pay higher wages. Greed and lack of vision ovecame the greater good of the area. Several companies looked to gain entry into the area throughout the boom years only to be denied. Too bad, G’ville was a great place as a kid to grow up in during those times.

My Dad was part owner of the tannery that existed where Colonial Tanning is now located. I remember coming home from college on Christmas vacation and working in the tannery horsing skins, hanging skins to dry and running the buzzle-buffer for hours as well as the splitting machine. My Dad was a custom splitter at the end of the booming days in Fulton County.

My Aunt and Uncle were managers at Garfalls in Johnstown and my mother, after learning to sew “Ossan Palming” at the old high school, worked in a factory for a while making gloves. She also worked in a factory that made those soft shoes-Whinnigs slipper factory. My mpther-in=law and her sisters worked in factories making gloves as well as sewing at home. I worked in St Thomas after high school before leaving to join my husband in the air Force. My dad commuted to Schenectady to work at the GE. My father-in-lay was a toggler and I remember him working two jobs a day…Levores and another I can’t recall. I treasured all the fine leather goods we were accustomed to having-from the “cow-girl” fringed jacket I owned as a kid to the beautiful suede jackets my parents had and the quality wallets from St Thomas and the fine gloves, that I still own. (1950’s-60’s)

Jules Garfall was my great uncle by marriage. My mom and most of her family worked in their factory at some point or another. We still have some of their originals at my mom’s house, including a leather Alice in Wonderland dress that was made for one of the World’s Fairs in NYC. Jules was also a very talented artist. My dad’s parents also worked in tanning (grandpa did the dyes, grandma did sewing) but not for Garfalls.

…so long and thanks for all the gloves.

Many thanks to Debbie and Larry Price for this remarkable study. I grew up in G’ville and my step-father was a chemist and executive in a leading tannery. I loved going to his place of work and smelling the finished skins stacked and ready for shipping. Dad carried this same leather scent on his clothing when he returned home for dinner, etc. Most of my childhood friends had parents working within the leather industry or Main Street retail shop sales. My last visit home was in 1978 where I viewed a shrinking down town and population. I am delighted to learn that a comeback exists and extensive renovation of the G’ville Public Library is nearing an end. I am proud to say that I was born and grew up in Gloversville, New York.

This is an interesting and well written synopsis of our region. I’ve lived in Fulton County morning entire live and I’m excited to see the revitalization taking shape. We are blessed to have the beautiful Sacandaga Resevoir and incredible Adirondack Park as a part of our region. With increased business expansion and revitalization our population and sociology-economic base will grow as well. Thank you for a wonderful article ??????

My Dad worked as slokum staker and worked 16 hour days stretching leather. Talk about work ethic. As a youth sometimes he’d bring me along to help horse up the skins on palettes. I’d fall asleep on topic some. He’s 88 years old now and going strong. My stepfather’s mother sewed thumbs on gloves. I do remember the strong odor while driving by the leather mills.

I grew up in Gloversville during the “boom” years. My uncle was a tannery owner and my father spent some time working in the local tanneries. Life was good then…the downtown vibrant and busy, providing a grand social playground…and many happy memories!

LIved on Hoosac street in J Town….can still smell “Karg BRos” tannery was right nearby,,house is gone now…along with the whole plant, Hard to believe,,,

Very well done. My grandparents were glove makers. My father was a shoe designer. I became a leather finish technician. From 1930-2017 the industry has supported 3 generations of my family.

leather is part of glamour like gloves boots thighigh crotchboots

Very well done. Having grown up in the region (johnstown) made this especially interesting. I remember checking out the Cayadutta Creek to see if it was flowing and what color it was. I’m glad to see the area being revitalized.

Thanks!!!!!!