What’s Good for the Heart May Well Be Good for the Brain

Over the course of her 25-year career as a neuropathologist, Ann McKee, associate director of Boston University Alzheimer’s Disease Center, has dissected thousands of brains — but two in particular stick with her. It was about a decade ago, and the brains belonged to identical twins who both died in their 70s. While one twin developed Alzheimer’s in his mid-60s, the other never showed any signs of cognitive impairment.

“Almost everything about them was the same,” McKee says, “Genes, education and even profession — both were chemical engineers.” But one major difference stood out. The twin who developed Alzheimer’s worked in a Union Carbide plant for three years where he was regularly exposed to large amounts of DDT.

In a 2009 study, McKee and her colleagues suggested that researchers need to more closely study the potential influence of life events on the development of Alzheimer’s.

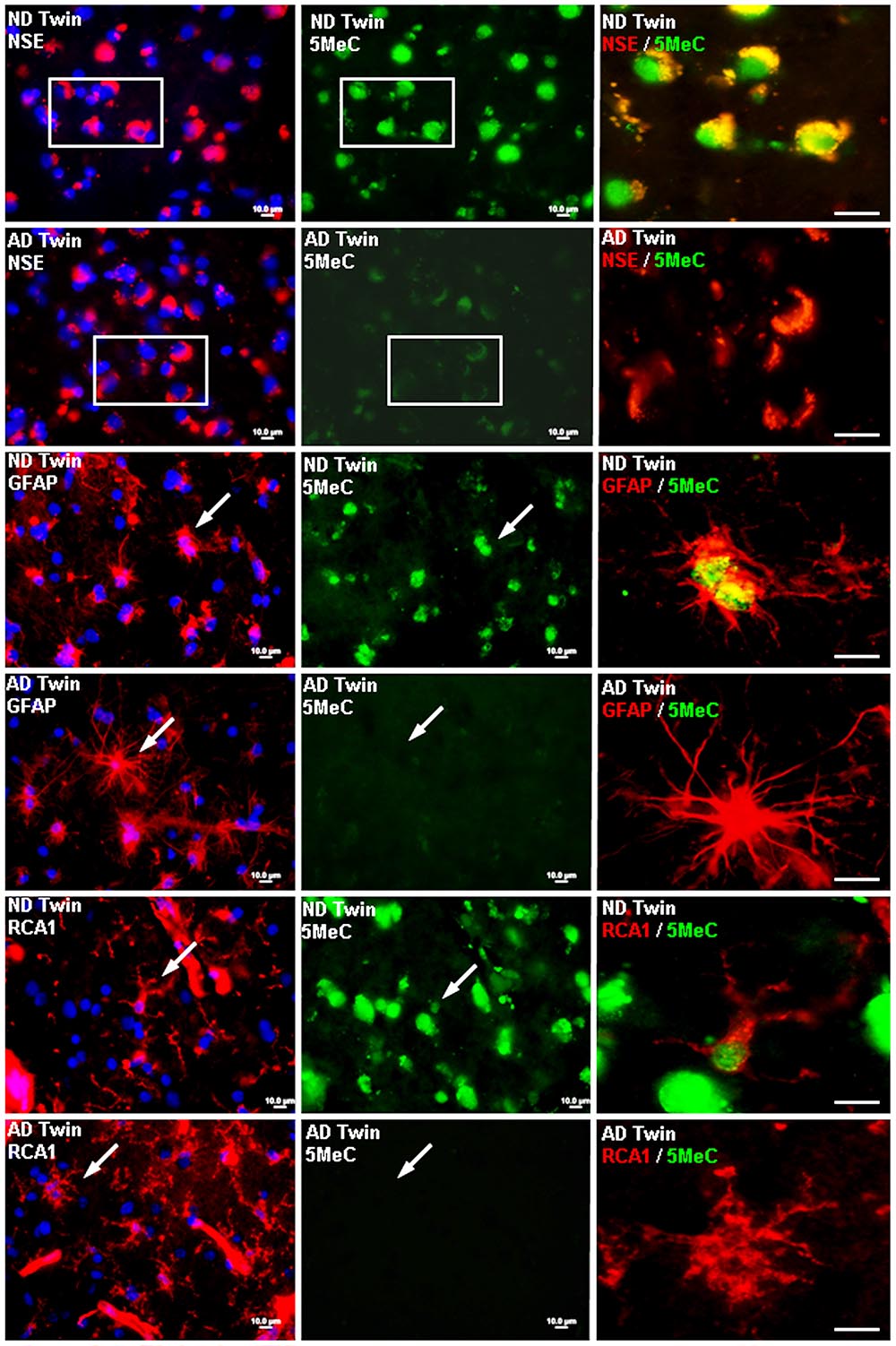

In 2009, McKee, along with a team of Arizona researchers, published a paper, “Epigenetic Differences in Cortical Neurons from a Pair of Monozygotic Twins Discordant for Alzheimer’s Disease” in the journal PlosOne, in which she offered a new way of thinking about the genetic mechanisms responsible for Alzheimer’s disease.

Instead of looking just for inborn genetic differences, McKee and her colleagues suggested, researchers also need to study the potential influence of life events. In her article, she reported that the cortical neurons of the twin with Alzheimer’s exhibited reduced levels of DNA methylation, a mechanism which controls gene expression, compared to those of the other twin. This is a finding that has been seen in other cases of the disease, and one that McKee suspects is attributable to the afflicted twin’s work in the Union Carbide plant. Subsequent research has lent further support to a link between DDT and the onset of Alzheimer’s. In a study funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and published in JAMA Neurology in 2014, scientists found that levels of DDE — a breakdown product of DDT — were 3.8 times higher in the blood samples of patients with Alzheimer’s than in those of comparable subjects without the disease. And DDT isn’t the only risk factor.

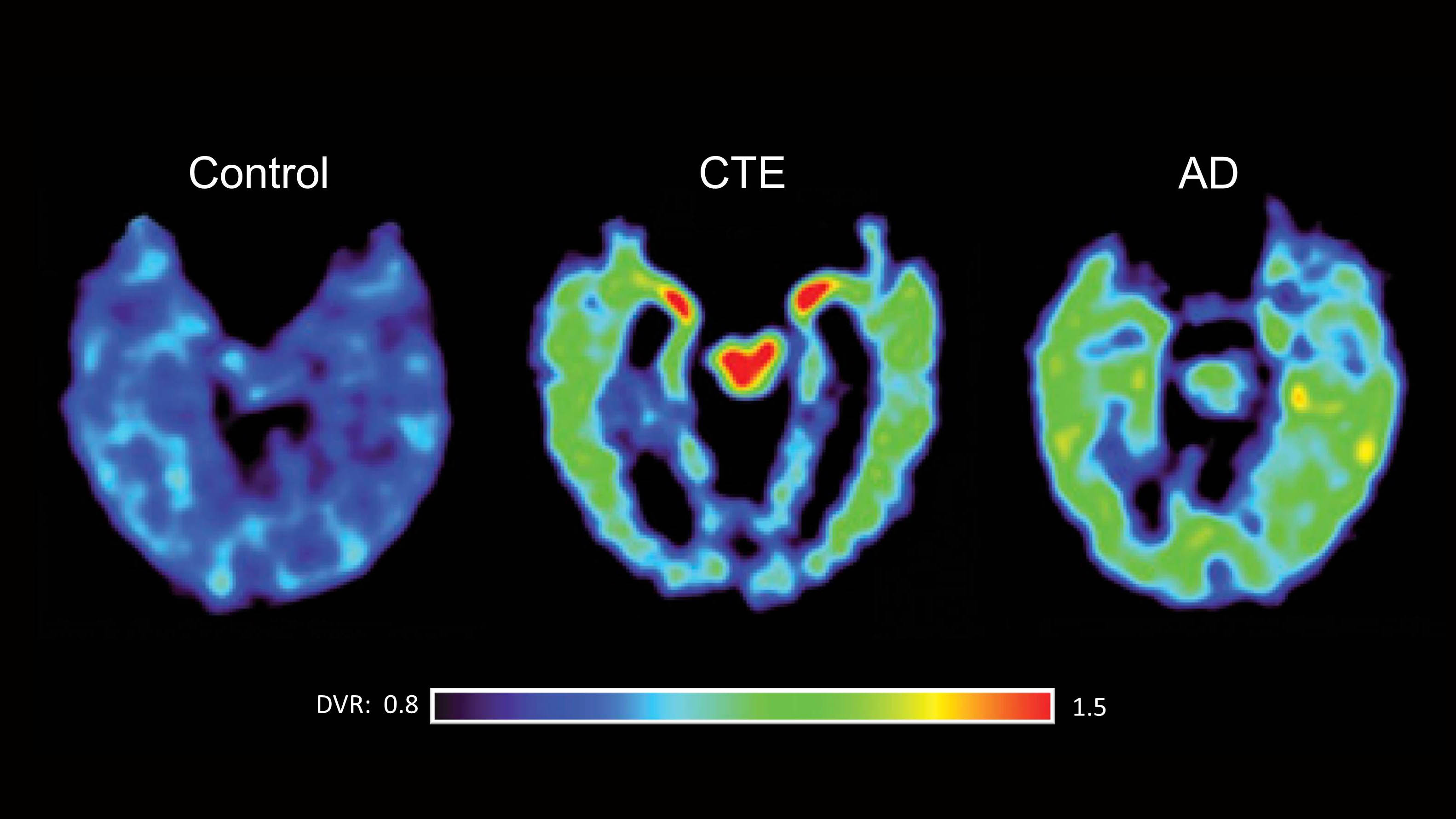

Studies have also found a link between brain injuries early in life (and sometimes not so early), and the onset of Alzheimer’s years later — including among Gulf War veterans who suffered traumatic brain injuries. Other studies have found troubling signs of cognitive impairment — the first phase of Alzheimer’s — among 9/11 first responders, suggesting that there might be a common environmental trigger. The lead author of that study, which found that 13 percent of 800 first-responders suffered from some form of cognitive impairment, while 1.2 percent had possible dementia, called the findings “staggering,” given that the average age of the respondents was only 53.

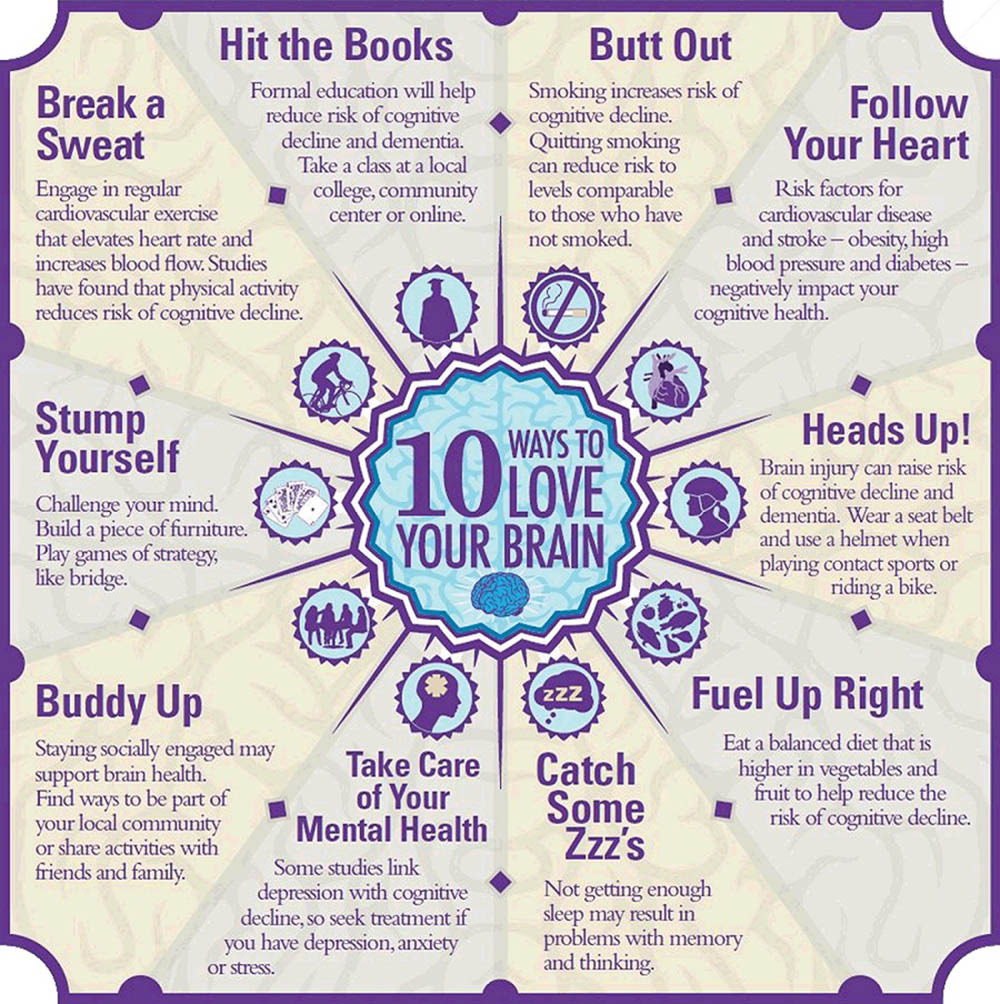

Similarly, scientists have also been studying associations between Alzheimer’s and a variety of other life events and lifestyle choices. Alzheimer’s Disease International, a federation of Alzheimer’s associations from around the world, summarized many of the key findings of this body of research in its 2014 report, “Dementia and Risk Reduction: An Analysis of Protective and Modifiable Factors.” The report identified four categories of risk factors: developmental (say, a lack of formal education); psychological (depression, for example, or a sleep disorder); lifestyle (smoking, diet, and so forth); and cardiovascular (hypertension or diabetes, among others) — all of which have been repeatedly linked to Alzheimer’s.

And yet for all of this, the general public still holds a variety of outdated ideas about the nature of Alzheimer’s — the most common being that this neurodegenerative disease stems solely from faulty genes. Indeed, a review article on the public’s understanding of Alzheimer’s disease published last year in the journal Alzheimer’s Disease and Associated Disorders noted that “while the public’s knowledge of genetic risk factors seems to be fair to good, knowledge of modifiable risk factors for dementia is poor.”

To back up this conclusion, the authors cited one study in which only about a quarter of respondents were aware that hypertension and high cholesterol increase an individual’s risk of developing dementia, and another study in which only about a third of respondents identified smoking as a risk factor.

The research on modifiable risk factors, of course, is still relatively new, and most of the studies conducted over the last two decades are observational, providing only links and associations. But the vast majority of clinicians who treat Alzheimer’s patients are now convinced that common-sense lifestyle adjustments can often help either ward off the disease or slow its progression. Researchers may not know precisely what exactly triggers Alzheimer’s in some people and not in others, but evidence suggests that what we eat, how we live, the way we think, and other factors are likely to play a role. As Robert Roca, vice president of medical affairs at Baltimore’s Sheppard Pratt Health System puts it, “The good news is that if you take simple steps that are beneficial for your overall health, you can reduce your risk.”

And just as public health campaigns extolling the benefits of diet, exercise, and quitting smoking have helped to raise awareness that reducing the risk of heart disease is at least partly within our control, so too, experts say, should more be done to increase public understanding of the controllable risk factors associated with Alzheimer’s. Indeed, some of the same measures that protect against cardiovascular disease — regular exercise, a diet heavy in fruits and vegetables — also protect against Alzheimer’s. “What is good for heart,” Roca says, “is also good for the brain.”

Those sorts of preventive insights are as crucial to combatting the disease as any hunt for a cure, suggests McKee, who has also done extensive research on neurodegenerative diseases in the brains of athletes like boxers and professional football players. Just as these individuals might have prevented their own disease by avoiding high-risk activities, McKee thinks much more needs to be done to educate the public on the types of activities that can increase risk for Alzheimer’s — as well as those activities that can decrease risk.

“We don’t have to step into the boxing ring, and we can also control vascular function, which often plays a huge role in Alzheimer’s disease,” McKee says.

“The brain and the heart actually have a lot in common,” she adds. “Both organs are responsive to what is going on in the rest of the body — and to our life experiences.”

When German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer published his first paper on what would become his eponymous disease in 1907, life expectancy in the United States, as in most western countries, was about 50. Given that the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease typically manifest much later in life — 81 percent of sufferers are over 75 — epidemiologists and others among Dr. Alzheimer’s contemporaries were initially slow to take notice of his findings.

By the latter half of the 20th century, however, average life expectancies began creeping into the 70s, and the scope of the disease became clear.

Today, an estimated 5.4 million Americans suffer from the disease, and that number is likely to triple by 2050. The disease affects one in nine people aged 65 and older. At age 85 and beyond, the ratio is one out of three. This year, 700,000 Americans are expected to die of Alzheimer’s — the nation’s sixth leading cause of death. The direct cost of treating the disease totaled $236 billion in 2015, and economists estimate that the unpaid labor provided by caregivers to Alzheimer’s patients last year amounted to another $220 billion.

And yet, experts estimate that only a tiny fraction of Alzheimer’s cases — about 1 percent — are purely genetic. These cases usually involve what’s called early-onset Alzheimer’s, a discrete variation of the disease that strikes before age 65 — and one that involves mutations in three specific genes.

In contrast, the 20 or so genes that are known to be associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s are susceptibility genes only, meaning that their presence could suggest a risk for the disease, but are by no means determinative. The most commonly studied is an allele known as APOE4, and scientists have associated it with an increased risk for developing late-onset Alzheimer’s. The problem: Some people with APOE4 never end up developing Alzheimer’s, and many people with the disease don’t have that gene.

Further complicating matters, demographics also appear to play a role. According to the Aging Demographics and Memory Study, which is funded by the National Institute of Aging, 11 percent of women over 71 have the disease, compared to just 7 percent of men. Scientists do not fully understand why the risk is higher for women, although one theory suggests that because men are more likely to die from heart disease in middle age than women, men who reach old age are likely to have a healthier cardiovascular risk profile and are thus less susceptible to developing Alzheimer’s.

African-Americans are also twice as likely to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease as whites, as reported in a 2009 review article in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. This discrepancy may also be explained by the higher prevalence of other health conditions in blacks such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Patients who develop Alzheimer’s typically go through three distinct phases. The first is the preclinical, in which there are detectable changes in the brain, but no symptoms. This can occur up to 25 years before the disease’s onset. This is followed by the onset of mild cognitive impairment and finally, dementia.

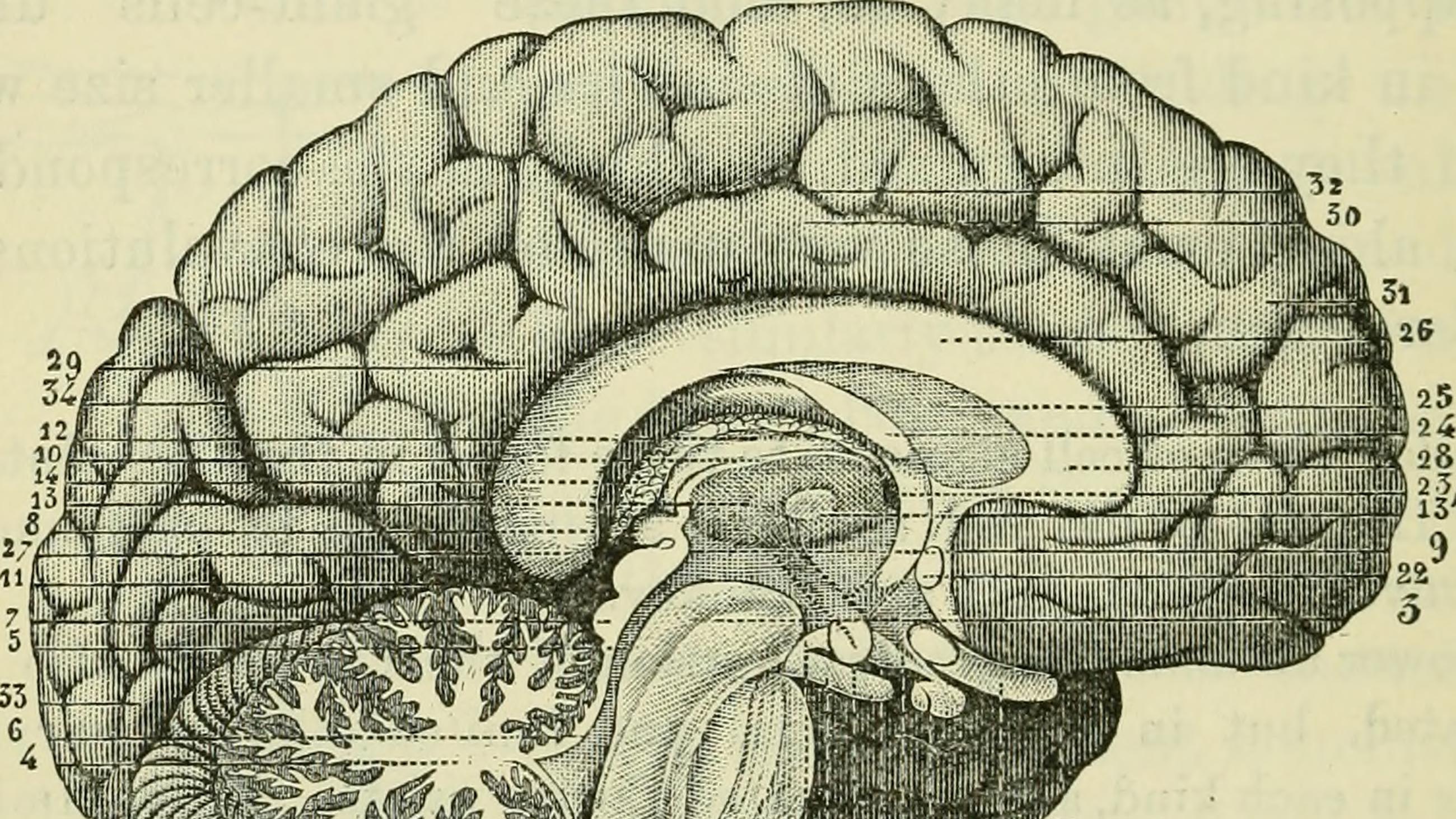

German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer published his first paper on what would become his eponymous disease in 1907.

Visual: National Library of Medicine

While Alzheimer’s can be definitively diagnosed only by a brain autopsy, a mental status exam can still be reasonably reliable, and clinicians are nearly unanimous in urging people who are troubled by problems with memory or executive functioning to seek help as soon as possible. “The longer you wait for treatment, the more limited your options are,” says Mitchell Clionsky, a neuropsychologist based in Springfield, Massachusetts, who has developed an assessment tool for Alzheimer’s. “I see MCI as a wake-up call that can enable patients to re-examine their overall health. At this phase, it’s still not too late to initiate interventions that can sometimes make a big difference.”

In fact, not all patients with cognitive impairment go on to develop Alzheimer’s. In a 2014 study published in the journal Neurology, which tracked about 500 patients with mild cognitive impairment, researchers at the Mayo Clinic found that after five years, 26 percent progressed to dementia without reverting back to normal, 36 percent retained their symptoms, and another 37 percent reverted at least once to normal cognitive function. “The reasons for such findings are not clear and deserve further study,” says Clionsky.

To encourage even earlier diagnosis, at this summer’s annual conference sponsored by the Alzheimer’s Association, a group of Canadian researchers led by Zahinoor Ismail from the University of Calgary proposed a new phase of the disease called “mild behavioral impairment.” The idea is to identify subtle psychiatric symptoms such as anxiety and social withdrawal that could be precursors cognitive decline.

For all of these efforts, however, Alzheimer’s diagnosis and treatment remain very much a blur of potential risk factors and confounding exceptions, often leaving the disease’s particular etiology in any individual case unclear. And it’s these sorts of incongruities that have led researchers to regard Alzheimer’s as a heterogeneous disease — one likely caused by a mix of genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors. Summing up the complex path to Alzheimer’s disease, James Hendrix, director of global science initiatives at the Alzheimer’s Association, puts it this way: “Genetics loads the gun, but environment pulls the trigger.”

Many Americans are familiar with Alzheimer’s drugs peddled on television. Most have limited effectiveness.

When Americans think about treatment for Alzheimer’s, what typically comes to mind are medications that are widely advertised on TV, like Aricept and Namenda. Unfortunately, the five FDA-approved Alzheimer’s drugs tend to be of limited effectiveness. Robert Stern, director of the clinical core at Boston University’s Alzheimer Center, notes that there hasn’t been a new drug in 12 years. “Medications can bring about some improvement for some people some of the time,” Stern says, “but they don’t modify the course of the disease.” These drugs are either cholinesterase inhibitors or NMDA antagonists, which each slow the breakdown and regulate the activity of key neurotransmitters involved in memory, respectively. A variety of new agents that use different mechanisms — such as those that are designed to attack proliferations of the proteins beta amyloid or tau, which are hallmarks of the disease — are currently in development.

Given both the unreliability of the drugs now on the market and all the research linking Alzheimer’s to lifestyle factors, many doctors now believe that treatment should focus primarily on prevention. These interventions take two forms: addressing other underlying health conditions that increase the risk of Alzheimer’s such as sleep disorders and hypertension and encouraging patients to make behavioral changes to improve brain health. “The best current tool involves not taking medication,” says David Bennett, director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Rush University Medical School, “but building up resilience.”

According to Bennett, much of the cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients is not explained solely by brain pathology — typically the presence of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles caused by the build-up of beta amyloid and tau. He demonstrated this in a landmark 2006 analysis of 134 patients culled from the thousands enrolled in his two major Alzheimer’s studies.

In a clinical exam taken shortly before death, none of the patients in Bennett’s sample were found to have experienced any cognitive impairment. And yet, brain autopsies showing the plaques and other physical signs would have suggested some of the patients were likely to have Alzheimer’s disease. The implications, Bennett says, were clear: “The brain is highly plastic and can adapt to injury. We need to do everything we can to try to help it fight against the disease.”

Bennett argues that people who received more education early in life have a greater amount of cognitive reserve — a catch-all term referring to a variety of cognitive skills — which often allows them to compensate for the damage to their brains. And he says those who did not receive as much formal education can improve their resilience by learning new skills — a second language, for example. This summer, Bennett wrote an article in Scientific American Mind titled “Banking Against Alzheimer’s.” The article highlights various steps that we can all take to age-proof our brains to make them more resistant to dementia, including remaining socially and intellectually active, achieving goals that we set for ourselves, and even helping others.

The concept of cognitive reserve dates back to the early 1990s when it was coined by Yaakov Stern, a professor of neuropsychology at Columbia University’s Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer’s Disease and the Aging Brain. In 1994, Stern published a groundbreaking paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association on a sample of about 600 patients aged 60 and older, which documented a clear link between educational and occupational attainment and a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s. “At first, the article got a lot of flak,” Stern says. “I received a letter from the wife of a Nobel Prize winner who called it idiotic because her husband suffered from Alzheimer’s. But I wasn’t suggesting that being brilliant means you won’t get the disease. “What I have been trying to get across,” adds Stern, who has since published a stream of papers on the notion of cognitive reserve, including neuro-imaging studies that connect it to regional cerebral blood flow, “is that experiences acquired over a lifetime can stave off dementia — often for several years.”

Today the concept of cognitive reserve is no longer quite so controversial, and neuroscientists have also documented how it mitigates various risk factors, including the presence of the Alzheimer’s susceptibility allele, APOE4. In a study published in JAMA Neurology in 2014, Prashanthi Vemuri, an assistant professor of radiology at the Mayo Clinic, reported that for carriers of APOE4 who also had what were considered to be high levels of intellectual enrichment, the onset of cognitive impairment occurred nearly nine years later than for APOE4 carriers with low lifetime intellectual enrichment.

Still, while experts suggest that it’s never too late to try to build up cognitive reserve, there is scant data that specific intellectual tasks or challenges, like doing crossword puzzles or reading books, can help to ward off the Alzheimer’s — despite much cultural hype to the contrary. Indeed, the difficulty in devising brain exercises that can be guaranteed to make our brains more resistant to the disease has not stopped numerous companies from trying to cash in on the promise.

“Brain games are already a big industry. They are a good idea, but some manufacturers sell products which are not backed up by much evidence,” says Ronald Petersen, who directs the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. In fact, last winter, the Federal Trade Commission slapped the brain-game company Luminosity with a $2 million fine for the false advertising used in touting its “Brain Training” program. “The best advice to keep dementia at bay,” says Prashanthi Vemuri, Petersen’s Mayo Clinic colleague, “is simply to keep a busy mind.”

Treating a troubled mind is also important, given ample evidence that some psychiatric diseases can also increase the risk of Alzheimer’s — chiefly sleep disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. The studies documenting these links invariably conclude that if more patients with these psychiatric diseases were to receive treatment, the incidence of Alzheimer’s would drop significantly. A leading advocate of this type of Alzheimer’s prevention is Kristine Yaffe, a professor of psychiatry, neurology and epidemiology at the University of California, San Francisco, who has focused her research on novel strategies for treating the disease.

In a 2011 article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Yaffe and her UCSF colleagues showed that elderly women with sleep apnea were about forty percent more likely to develop either mild cognitive impairment or dementia than controls. They traced the impairment in cognitive functioning not to the loss of sleep, but to hypoxia — a drop in the oxygen level in the blood. Likewise, a study of 181,000 veterans published by Yaffe and her colleagues in 2010 showed that veterans with PTSD were almost twice as likely to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease as their counterparts without PTSD. Yaffe noted that post-traumatic stress disorder results in elevated cortisol levels — a finding which is also associated with cognitive impairment — but she stressed that the precise biological mechanism linking the two disorders requires further study.

While depression has often been associated with Alzheimer’s, researchers are not entirely sure whether it is an independent risk factor or a precursor. In 2013, the British Journal of Psychiatry published a meta-analysis of 23 studies that tracked about 50,000 adults over the age of 50 over a median of five years. It found that those with depression were 65 percent more likely to develop Alzheimer’s.

For all of this, perhaps the most significant insight that Alzheimer’s researchers have gained over the last 20 years is that what’s good for the heart is actually good for the brain, too. Nearly all the common cardiovascular risk factors — from smoking, hypertension, and high cholesterol to diabetes and obesity — are also linked to increased risk for Alzheimer’s.

Smoking for example, damages the heart by causing a narrowing of blood vessels. It turns out it does the same inside the brain. In its 2014 report, “Tobacco Use and Dementia,” the World Health Organization concluded that 14 percent of all the Alzheimer’s cases in the world are potentially attributable to smoking.

Hypertension, meanwhile, is as toxic to the brain as it is to the heart, but for a different reason. “Reducing hypertension is critical in preventing [Alzheimer’s disease],” says Mark Bondi, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. This is because problems with blood flow can cause a build-up of beta amyloid.

In a 2015 paper in JAMA Neurology, co-authored with psychologist Daniel Nation of the University of Southern California, Bondi showed that higher pulse pressure, an index of vascular aging, was associated with more rapid progression to dementia. Bondi adds that hypertension and Type 2 diabetes constitute “a synergistic risk,” so it’s also particularly important to treat diabetes. “And it’s not just diabetes and obesity that need to be treated,” says internist Paul Crane of the University of Washington. “So, too, do high glucose levels.” In a 2013 New England Journal of Medicine study of about 2,000 participants in the University of Washington’s Adult Changes in Thought study, Crane documented how even patients without diabetes often face an increased risk of Alzheimer’s due to their high glucose levels.

The two primary takeaways from these and other studies are actually quite simple: Alzheimer’s has much less to do with one’s genes than most Americans realize, and lifestyle changes often help our brains as much as they help our hearts.

Several studies show that improving our diets by eating primarily plant-based foods and reducing our intake of red meat can be as effective in combating Alzheimer’s as in combating heart disease. In a 2015 paper published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, Martha Clare Morris and her colleagues at the Rush University Medical Center showed that the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet — a hybrid of the of the well-known Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet promoted by the National Institutes of Health — lowered the risk of Alzheimer’s by as much as 53 percent in subjects who adhered to it strictly, and by about 35 percent in those who followed it moderately.

Aerobic exercise protects against Alzheimer’s indirectly through its impact on heart health, but it also has the potential to slow down deterioration of the brain. In a neuro-imaging study published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences in 2007, Bonita L. Marks, a professor in the department of exercise and sport science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, showed that greater aerobic fitness was associated with more white matter integrity in several regions of the brain. Likewise, in a 2016 paper published in Alzheimer’s Dementia, Dane Cook, a professor of kinesiology at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, showed that regular physical activity can protect against temporal lobe atrophy.

“Staying physically active,” says Creighton Phelps, deputy director of the National Institute of Aging’s division of neuroscience, “is a key part of Alzheimer’s disease treatment.”

Despite the decades of research linking environmental and lifestyle risk factors to Alzheimer’s, public service efforts to get the word out have begun only recently. In 2013, the World Dementia Council, which consists of experts on neurodegenerative diseases from Canada, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, and the United States, among other countries, asked the Alzheimer’s Association to evaluate all the data on risk factors. The resulting paper, “Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk-factors for cognitive decline and dementia: A population-based perspective,” published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia in the spring of 2015, was unequivocal in its conclusion: “[T]here is sufficiently strong evidence, from a population-based perspective, to conclude that regular physical activity and management of cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, obesity, smoking, and hypertension) reduce the risk of cognitive decline and may reduce the risk of dementia.”

That June, during the Alzheimer’s Association’s “Brain Awareness Month,” the group rolled out a campaign called “10 Ways to Love Your Brain.” These tips, which are still prominently featured on its website, include such measures as cutting out smoking, eating a balanced diet and getting treatment for various mental health conditions.

The American Heart Association provides a clear blueprint for this type of public education. In the early 1960s, it started an aggressive campaign to inform the American people of the links between risk factors such as smoking and hypertension to coronary heart disease. The effects were dramatic. By 1990, the heart disease mortality rate in the United States had declined by about 50 percent. Today, the American Heart Association maintains that 90 percent of cases of heart disease can be prevented.

One reason that public health advocates have been relatively slow to jump on the Alzheimer’s bandwagon is that the research on risk factors remains somewhat tentative. At present, it points merely to correlations, not to definitive causes or cures. “The Alzheimer’s data are largely observational and there have been no randomized clinical trials,” says David Bennett of the Rush University Medical School. Likewise, while many of the same factors increase the risk for both heart disease and Alzheimer’s, the links to heart disease invariably tend to be stronger. After all, Alzheimer’s is a particularly complicated disease and many different pathways can lead to it.

Still, experts say there is enough evidence to suggest that lifestyle modifications are likely to matter — and that more people should be made aware.

For decades, Ann McKee of Boston University’s Alzheimer Center has also served as a pathologist for the Framingham Heart Study, which has been documenting the risk factors for cardiovascular disease since 1948. Back then, the causes of this epidemic were largely a mystery. She says she is hopeful that researchers will also eventually be able to pinpoint the major causes of Alzheimer’s.

“In contrast to heart disease, the Alzheimer’s field is just getting started,” McKee says. “And all kinds of negative life experiences can damage brain health, from exposure to environmental toxins to stress and poverty. We need to know more about what the precise effects are, and public health measures are definitely part of the answer.”

Joshua C. Kendall is a frequent contributor to Undark. His work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, Psychology Today, and BusinessWeek, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I remember hearing on the radio, years ago, that a study had found that an Alzheimers risk factor is a diversity of jobs and perspective-altering experiences throughout one’s life. In other words, people who work at the same job, do pretty much the same things and routines throughout their lives, may be at a higher risk than those who make big changes, think outside of the box in terms of lifestyle and habits, etc. However, in looking for that info online now, I am not finding anything specifically about that. Can anyone help?

As we learn more about the brain’s drainage system, the glymphatics, we will better understand how to further mitigate risks. Effective drainage of beta-amyloid prevents its build-up, after all. This is why sleep is so critical. It’s when the brain drains and cleans house.

Here’s my non-scientific theory: as drugs are being used to ‘treat’ (actually mask or offset) the effects of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease, these are now expressing themselves through Alzheimer’s–ie the brain, instead of the heart. The rise in Alzheimer’s is due to longer life expectancy, especially for people with heart disease thanks to the effects of their heart medication.