Genetic Differences in Cell Line Could be Big News for Researchers

Thomas Hartung was part of a team trying to understand how estrogen affects human cells. A professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, he and his team, along with a second group at Brown, needed breast cancer cells on which to test the hormone, so they went through the relatively ordinary process of ordering some from a cell bank.

They did not exactly get what they expected.

Up to 36 percent of the cell lines used in experiments are thought to be contaminated or mislabeled, calling the findings into question. But a study by Hartung and fellow researchers, published last week, presents a different problem entirely: the possibility that mutations are changing the cell lines themselves, leading to distinct subpopulations of cells.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, found that cells thought to be identical reacted differently to the same chemicals.

Hartung said he and his team, along with the team at Brown were conducting research for the Human Toxome Project, an effort to better understand how different chemicals affect human health. The cells they bought, known as MCF-7, were originally from the tumor of a patient with breast cancer and have been used in research for over 40 years.

(One author of the paper is a consultant for chemical and pharmaceutical companies and owns stock in the biotech company Semma Therapeutics, and two other authors are employees of Agilent Technologies Inc., which “manufactures and sells products used in this study,” according to the paper.)

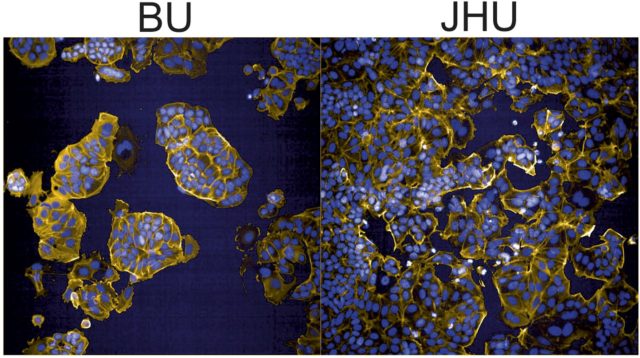

“The difference between the two labs were enormous,” Hartung said. The most striking difference was the way they grew: At Johns Hopkins, the authors noted that the cells grew in a flat cobblestone pattern, while at Brown they grew in large separated clumps. The different growth turned out to be a result of genetic variation. The team concluded that the cells must have had the variation before they were shipped out, although Hartung said he did not think the differences were the fault of the laboratories that supplied the cells. Instead, he added, the differences probably lie in the fact that by definition, cancer cells act differently from normal cells and have more mutations.

“This is a bit of an elephant in the room and it is good that people like Thomas [Hartung] are willing to discuss it in open papers,” said Glyn Stacey, a microbiologist at the U.K.’s National Institute for Biological Standards and Control. In fact, Stacey said that when it comes to problems with cells in biological research, this paper may have only scratched the surface.

“For a long time it has been a problem with people publishing about a cell line that isn’t even the right cell line,” Stacey said. “They may have done this for decades, and of course it is a professional reputation issue if they have to admit that they actually haven’t been using the right cells. So these things very rarely get out into the public.”

If these results are true, they could have a big impact on biological research, said Warren Casey, director of the Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods at the National Institutes of Health. While there have been problems in past decades with researchers using cells that were labeled incorrectly, Casey said he hasn’t heard of cells actually splitting into different genetic variants like those described in the paper. But before he can trust such results, he would want other researchers to order the same cell line and see if they get similar results.

“It is unusual for sure, and is something that needs to be replicated for sure,” he said.

It is possible that the genetic differences were a rare anomaly. But if not, Hartung said researchers might need to discuss reliable ways to use cancer cells like MCF-7 for research. The International Cell Line Authentication Committee sets standards for testing cells and making sure they all come from the same lineage, but Hartung recommends that researchers go further and verify the cells independently.