Quoting the Gray Lady Ain’t Cheap

Last month, two University of California professors published a scholarly book on health news coverage in which they used numerous examples from the press to illustrate their arguments. Every publisher and broadcaster granted them permission to reprint material without charge, except one: The New York Times.

In a move that drew jeers from a variety of press watchdogs and bloggers, the newspaper — which itself quotes other published sources daily — charged the authors $1,884 to use three quotations, each roughly 90-100 words long. The longest was 102 words. It seems the book’s publisher, Routledge, told the authors that quotations of more than 50 words exceeded what it understood to be permissible under “fair use” rules. The publisher negotiated the terms with a licensing agency representing The New York Times, and then told the authors they were responsible for paying the fee, which amounts to more than $6 per word.

(For reference, the preceding paragraph is 102 words long.)

So was the fee exorbitant? Charles L. Briggs, an anthropologist at the University of California, Berkeley, and one of the authors of the new book, surely thinks so. “This violates fair-use principles,” he said in an email message to Undark. “This was not about having to pay 1,884 bucks. This is about the rights of scholars to enjoy the same rights that journalists demand.”

The book in question, “Making Health Public, How News Coverage Is Remaking Media, Medicine, and Contemporary Life,” is an academic tome and clearly not intended for a mass audience. It sells for $140 in hardcover and $44.95 in paperback. Briggs and his co-author, Daniel C. Hallin, a communications professor at the University of California, San Diego, say they received an advance of just $800.

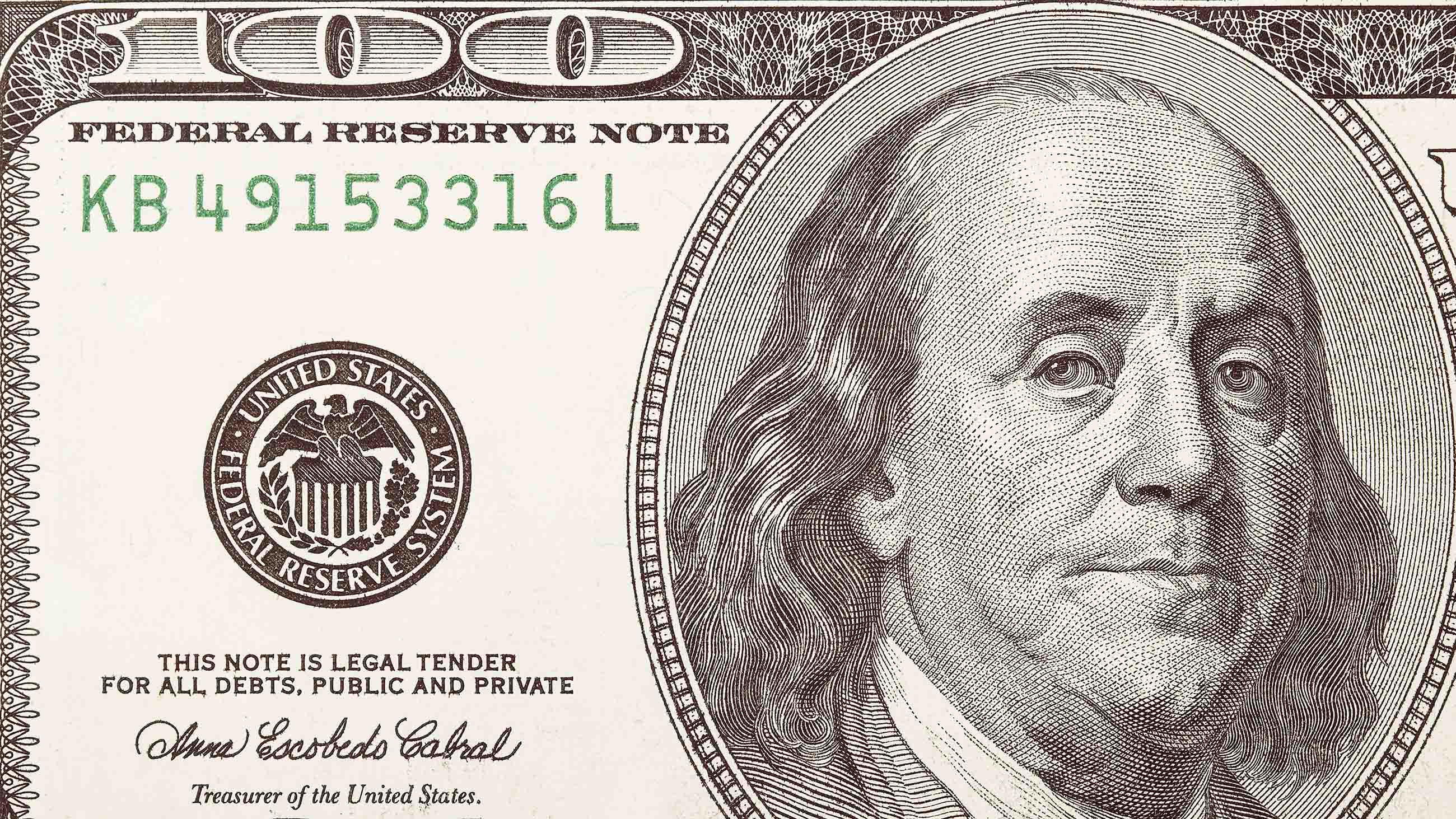

In a move that drew jeers from press watchdogs and bloggers, The New York Times charged two book authors $1,884 to use three quotations, each roughly 90-100 words long. The book’s publisher, Routledge, told the authors that quotations of more than 50 words — about the length of this caption — exceeded fair use. (Visual by iStock.com)

In response to the licensing fee, the pair launched a Kickstarter campaign last week in an effort to recover the $1,884 charge — and with 25 days left, they’re more than two-thirds of the way there, having earned nearly $1,400 as of this writing. As part of the campaign, they also took the opportunity to lambaste The New York Times, calling its fee “an arrogant rejection of the principle of fair use that is ironic for an organization that presents itself as a defender of freedom of expression.”

The concept of fair use, according to the Center for Media & Social Impact at American University, is defined as “the right to use copyrighted material without permission or payment under some circumstances — especially when the cultural or social benefits of the use are predominant.” In other words, fair use allows scholars and journalists to quote from published works — just not too much.

But there’s the rub: How much is too much? American copyright law offers only the roughest of guidelines, and not surprisingly, U.S. courts are often busy adjudicating the topic, which can seem situational and subjective. The folks at American University, meanwhile, have published a detailed compilation of fair-use best practices for both journalists and scholars, and for their part, Hallin and Briggs are convinced that their quotations fell well within the boundaries.

Jordan Cohen, a spokesperson for The Times, said in a prepared statement circulated to the media that the newspaper supported fair use, and that as a content producer itself, it frequently finds itself on both sides of what can be a roiling debate.

But, Cohen added:

It would be impossible for us to make “fair use” judgments for the vast number of people and organizations that wish to use New York Times content — we leave that to them and their attorneys to work out for themselves, just as our lawyers make judgments about fair use for The New York Times. If those third parties don’t feel comfortable that their proposed use of our content is a fair use, then we are happy to make the content available through our licensing program.

Our journalism costs money to produce and we share royalties with the reporters, photographers and others who helped create it.

When pressed, Cohen would not say how the newspaper arrived at the $1,884 fee for the Routledge book, but Corrine Pulicay of PARS International, the reprint and licensing agency that represents The Times, said “the fees for republishing licenses begin at $250-$500 and are based on content requested and the rights required.” She said that PARS does not advise on fair use, and that a client must decide “whether or not to publish copyrighted material under fair use standards, at his or her own risk.”

The person who handles permissions for use of Routledge content, Elizabeth Sheehan, said she was not party to the negotiations on this book, but she did say that 50 words is the limit that Routledge itself sets before quoted content from its copyrighted material must be licensed by third-parties.

Still, she characterized the fee demanded by the Times as “quite a premium charge.”

“The reward people get [for donating] is we put their names on a letter of protest we’re going to send to The New York Times and Routledge,” Briggs said of his Kickstarter fundraiser. “We could eat the cost of this if we really had to, although neither of us is the kind of scholar who has big grants.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

As an academic author, I have ejected quotations from a book numerous times because the publisher said we’d have to get permission, and the fees were beyond what they authors could afford. Most academic authors do not get any kind of advance and have to cover any copyright fees out of pocket. I am surprised by the very-conservative limit of 50 words chosen by Routledge, but these costs are often very expensive at academic publishers as well. Personally, the worst offender is not a quotation, which is covered by fair use, but rather tables and charts. A table or chart is not covered under fair use even if the table or chart is only 20 words because it’s classified as a graphic or image. I’ve seen some very outlandish charges for short tables by numerous publishers. Again, I just do my best to avoid using anything that would need copyright clearance.

One consequence of the Times’ policy will be that writers will paraphrase from works, instead of quoting them directly. This will lessen the degree of factual accuracy and diminish the clarity of scholarly discussion. It is surely a poor application of the fair use principle, and it’s to be hoped that the Times will reconsider its position. Fair use should mean the encouragement of scholarly dialogue, not the muzzling of it.

Agreed, Roxana. The policy is bad for everyone. Except, I suppose, the Times, which pockets the money.

As an author who has dealt with clearing permissions dozens of times, I see this as Routledge’s fault for being overly cautious about what constitutes fair use. If they had been more reasonable, the authors would have gone ahead and used the quotes, and there would have been no repercussions. As the Times spokesman said, the company (or rather its licensing agency) doesn’t make fair use judgments. They just process requests from people who have decided (or been told by their own publisher) that they need permission. I’ve been charged exorbitant fees from a public university for reprinting photos from its archives and from a small literary press for using four lines of a poem, even though the poet had given me permission. A college at Oxford charged me hundreds of dollars to reproduce a drawing from Isaac Newton’s notebooks.

It’s disappointing that the Times would charge for such a use. It hurts non-fiction authors who often don’t have that kind of money to spare, and it gives copyright a bad name, making it more difficult for those of us trying to ensure that copyright doesn’t become so eroded that it fails to support the ability of full-time writers to keep writing.

It’s also disappointing that the Times – so far at least – has foregone the opportunity to do the right thing and abate that charge. Maybe the Public Editor ought to weigh in here. Or maybe the Haggler (the Times’s consumer advocate).