The Trouble with Labeling Cholesterol

Physicians have long believed that “good” cholesterol, or high-density lipoproteins (HDL), can protect patients against cardiovascular disease. Theory suggests that adequate amounts of the “good” can help prevent buildup of the “bad.” But several recent studies suggest that the “good cholesterol” label is a potentially risky oversimplification.

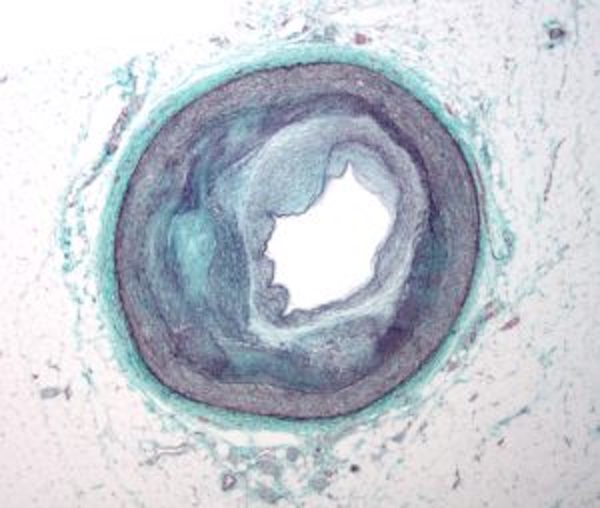

This cross section of an artery shows the narrowing walls caused by plaque buildup in people with cardiovascular disease. (Visual by Wikimedia Commons)

Last month, researchers from the University of Maryland reported that high levels of HDL are not as protective as was previously thought. The results, which were based on an analysis of data from 3,600 people in the Framingham Heart Study database, revealed that the negative impacts of having high levels of “bad” cholesterol (low-density lipoproteins, or LDL) and other blood fats known as triglycerides tend to outweigh whatever benefits HDL might provide.

In fact, if triglycerides rise above a certain level, robust levels of HDL fail to reduce cardiovascular risk at all.

The finding comes in the wake of several others published this year that identify circumstances in which HDL fails to play its typical role. Two studies, published in Science and PLOS One respectively, looked at people who had mutations in a critical liver protein called SCARB1. Despite high HDL levels, they developed atherosclerosis, a buildup of cholesterol plaque in the blood vessels which can lead to heart attack or stroke.

In a healthy person, HDL droplets are thought to prevent atherosclerosis by removing LDL from the vessel walls and carrying it through the bloodstream to the liver. As they flow by, the SCARB1 protein snatches the droplets and helps them dock on to liver cells, unloading the bad cholesterol for processing out of the system. Its link to reducing levels of LDL – with its known health risks – earned HDL the “good cholesterol” moniker.

But for someone with a SCARB1 mutation, the receptor may not work, meaning that the process of depositing LDL for clean up by the liver will fail. The obvious question in this case is: how many people are known to carry such mutations?

Though some SCARB1 mutations are exceedingly rare, according to Dr. Annabelle Rodriguez-Oquendo, the one reported in the PLOS One article is likely present in about 10 percent of the U.S. population. And data from the National Center for Biotechnology Information suggests it may be even more common, occurring in anywhere from 12 to 21 percent of the population. But that information is still being assessed in terms of patient treatment.

Hanna K. Gaggin, a cardiovascular specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital, says the careful assessment makes sense. “In order for something to be standard of care in this field, there needs to be a lot of robust studies,” she says, adding that physicians rely on their clinical training to spot irregularities as well as using calculations based on long-time cholesterol and health data.

Genetic testing can reveal SCARB1 mutations but more study may be needed to confirm the questions raised by the recent studies. And question of whether HDL should be labeled as “good” also remains one for continued debate.

Gaggin says the label is very simplified, but being able to encourage her patients to stop smoking, exercise more and lose weight in order to raise their “good” cholesterol levels is helpful. “My job is to motivate patients to change their lifestyle and HDL levels are tangible and help them track their progress,” she says.

Rodriguez-Oquendo is more critical. “We’ve been saying for a long time now that there are patients that have a high level of HDL and it’s not helping them,” she says. She tends to see the “good” label as a misleading oversimplification.

Daniel Rader, lead author of the Science study, echoed this sentiment, saying that such a label may give physicians and patients a false sense of security when HDL levels are high.

For that reason, he says, “we should probably be purging ‘good’ cholesterol from our lexicon.”

This post has been updated to clarify that high levels of LDL and triglycerides tend to outweigh the benefits of HDL.