In the War on Zika, a Persistent Fog

Dora Helena Ferreira, a 20-year-old student, was about three months pregnant in the spring of 2015 when she began having fevers and sharp joint pain that kept her from bending her fingers. Mosquitos are a common sight in Ferreira’s neighborhood in the northeastern city of Barbalha, Brazil, and when she arrived at the nearest hospital with a red rash covering most of her body, she was immediately tested for dengue. But the exams came back negative and she was discharged.

“Maybe April, I think,” Ferreira told me recently, speculating on when she might have been bitten by a disease-laden mosquito. “I couldn’t do this,” she said, flexing her index finger. “It would hurt when I tried to bend it.”

Located near a fruit stand, Ferreira’s railroad-style house faces an otherwise charming cobblestone street that, on a recent visit, was found littered with trash and wet with sewage water. Inside her home, Ferreira recalled that her grandmother sometimes had to swing a broom at the mosquitos swarming around the living room fan, while a nearby chair could turn completely black with the insects. All seven members of Ferreira’s family had been diagnosed with dengue at some point, so her own symptoms, while worrying, were not particularly surprising.

RELATED STORY Is the answer to the Zika outbreak the eradication of all mosquitos, as some suggest? Not everyone thinks so.

Two weeks after that initial visit, Ferreira was back at the hospital. She was given a tentative diagnosis of dengue, but her doctor, Jácia Coelho, wasn’t so sure. Ferreira was among a growing number of her patients at the public hospital of Barbalha presenting with what she described as a “weaker dengue” — and they were showing up at an alarming rate. In fall of last year, Coelho began contacting her network of doctors — many of them from the neighboring state of Pernambuco — to see if they were experiencing similar outbreaks. They were, and they were reporting unusual numbers of newborns with microcephaly, a condition in which a baby’s brain is underdeveloped, causing the head to be smaller than normal.

Ferreira’s son, João Artur, was born this past November with a head circumference of less than 31 centimeters, greater than two standard deviations below the mean for newborns. It was only around that time that the Brazilian medical community had begun making the connection between this “weaker dengue” and an explosion of microcephaly. In 2014, the entire country of Brazil reported 147 microcephaly cases, including just 12 in Pernambuco. By the time João Artur was born, Pernambuco alone had 646 microcephalic newborns, and a nationwide public health emergency was declared.

Dr. Coelho was outraged. “Nobody sounded the alarm regarding a potential risk to pregnant women,” she said, describing a woeful lack of directives from the health ministry on how to handle these fast-multiplying cases, or even whether the rise of this “weaker dengue” had anything to do with the increased incidence of the birth defect.

Ferreira’s ultrasounds during pregnancy showed no sign of abnormality, but once João was born, it was clear: His postpartum tomography showed striking lesions to his brain cortex. As with most pregnant women currently suspected of Zika infection, Ferreira’s diagnosis was made based on a retrospective analysis at the onset of symptoms — a point at which it was far too late for João.

Of course, evidence that something was amiss had been mounting for nearly a year before Ferreira’s son was born, and researchers elsewhere in the world have finally begun developing a number of tools that can help to more quickly diagnose emerging illnesses — particularly those in underserved communities. Meanwhile, complaints of a sluggish and messy official response to the rising outbreak, possibly slowing the movement of such tools from labs into the field, have become common — as have charges that women like Ferreira have been given unrealistic reproductive advice in regions where their options are both politically and economically limited.

But it was only at a workshop held in March, in the coastal city of Recife, however, that it became clear to me why the response to the spreading crisis was so slow in Brazil, and why a more coordinated effort to understand the Zika virus, to understand its unique risks to pregnant women and its connections to microcephaly, and to diagnose Zika exposure far more quickly in vulnerable populations, has been so slow to develop.

It will be obvious to anyone arriving in Recife why it is the epicenter for the current spread of so many viral blights, from dengue and chikungunya to Zika. The city’s proximity to both the equator and the Atlantic Ocean creates a suffocating climate — precisely the sort of hot and humid breeding ground favored by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, that nimble vector so notoriously effective at spreading some of the hemisphere’s most pernicious diseases.

I was born and lived in Recife, the capital and largest city in Pernambuco, until I was 12. I then moved with my family to Boston, where my parents pursued postdoctoral studies in medicine. I followed their interests tangentially, earning a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and later a master’s degree from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

When researchers in Recife began organizing a workshop on the Zika virus last November, they contacted me at my current home in Chile to ask about American scientists who might be interested in participating. I immediately thought of Irene Bosch.

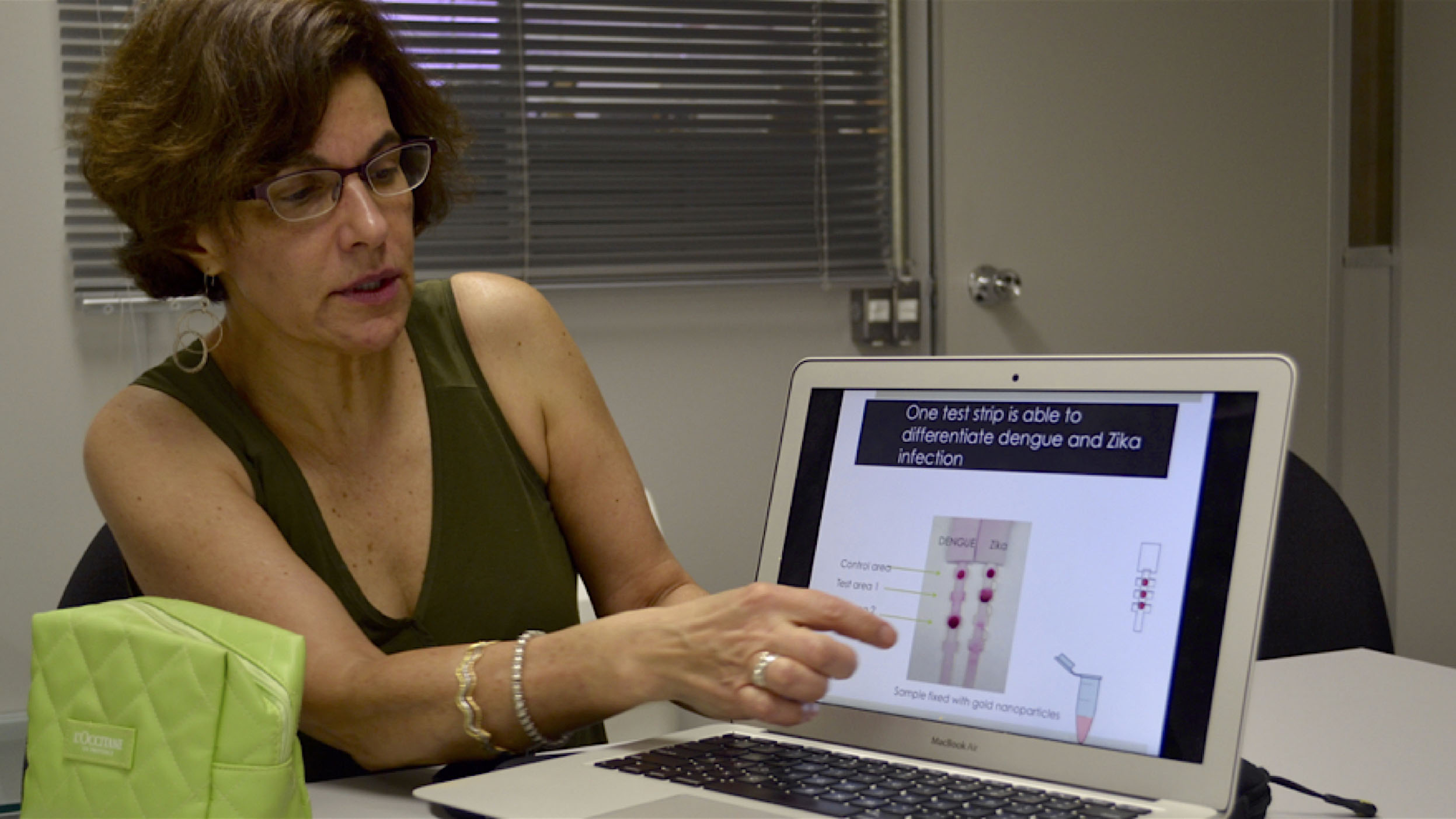

Bosch is an MIT-based expert in tropical viruses – particularly dengue — whom I had met during my studies in the United States. For years, she has been busy building simple and innovative viral diagnostic tools for use in low-resource regions. As one of the many scientists around the world working to develop a test for Zika, she’d recently been working to develop a nanoparticle-based paper diagnostic test that could quickly distinguish the disease from others like dengue.

Such a tool was desperately needed. Beyond a symptoms-based diagnosis of Zika infection — inherently imperfect but often the only one available in many far flung areas of Brazil — blood or tissue samples must be sent to a lab within the first week of infection. Technicians can analyze the samples using a molecular technique known as reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, or RT-PCR, which identifies the presence or absence of viral RNA.

Two samples of amniotic fluid from microcephaly cases were analyzed using this method during the first official inquiry into the mysterious virus, and Zika RNA was uncovered in both. It was on the basis of these findings that Brazil’s ministry of health established a task force to investigate the probable link.

But speedier diagnoses would be needed to really begin curbing and treating exposures, so organizers invited Bosch to the workshop, and I joined her as a technical assistant. Neither of us realized the mess we were walking into when we arrived for the conference in March.

I was accustomed to Brazil’s health politics, but the sheer number of obstacles arising from interpersonal and structural politics in the midst of the Zika outbreak continues to be, in a word, breathtaking. Turf wars, for example, have dictated which hospitals a researcher interested in delving into the Zika crisis can work with, and which staff must be involved. Foreigners like Bosch, who had real insights to share on viral pathology and infection testing encountered bureaucratic roadblocks for months, preventing them from accessing the labs, blood samples, and personnel that could facilitate a substantive knowledge exchange — the sort of fertile interaction among experts that might have proved useful when Coelho was encountering a deluge of patients like Ferreira.

And yet, from the first day of the workshop, which was organized by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, or Fiocruz, the tension between clinicians, epidemiologists, mosquito-control specialists and local officials was palpable, and disagreements boiled over into the hallways.

Some experts described the connection between Zika and microcephaly as established science — a position endorsed not just by the Brazilian government, but by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Others, mainly epidemiologists, continued to quibble, warning of the difference between correlation, causation and coincidence. (Scientists offered more direct proof of the Zika-microcephaly connection this week, in the form of animal studies. In two out of three studies published on Wednesday, mice injected with Zika gave birth to babies that showed signs of microcephaly.)

At the workshop, participants bickered over the Brazilian government’s response to the crisis, widely panned as slapdash as it juggled the widening outbreak against the backdrop of an economic recession, a major corruption scandal, and impeachment proceedings against the country’s president. And still others complained of the pressure many Brazilian researchers were under to publish in the scientific literature during what was a growing public health emergency —one that remained woefully hindered by the inability to quickly diagnose infection.

“I didn’t care about publishing in Nature,” said Dr. Gubio Soares Campos, a physician-researcher from the state of Bahia, when his colleagues criticized him for not publishing his first findings on the Zika virus. Campos was profiled by The New York Times in February.

“I wanted to have information to give my patients,” he said.

Like many researchers outside Brazil, Bosch had been busy tweaking and developing her Zika diagnostic tool using whatever blood samples she could acquire. They were almost always old — useful to a point, but limited in their ability to help fine-tune a faster viral detection method in a way that could, eventually, actually help to curb the burgeoning epidemic.

“I grew the virus in the lab but I never saw it with a patient,” Bosch told me.

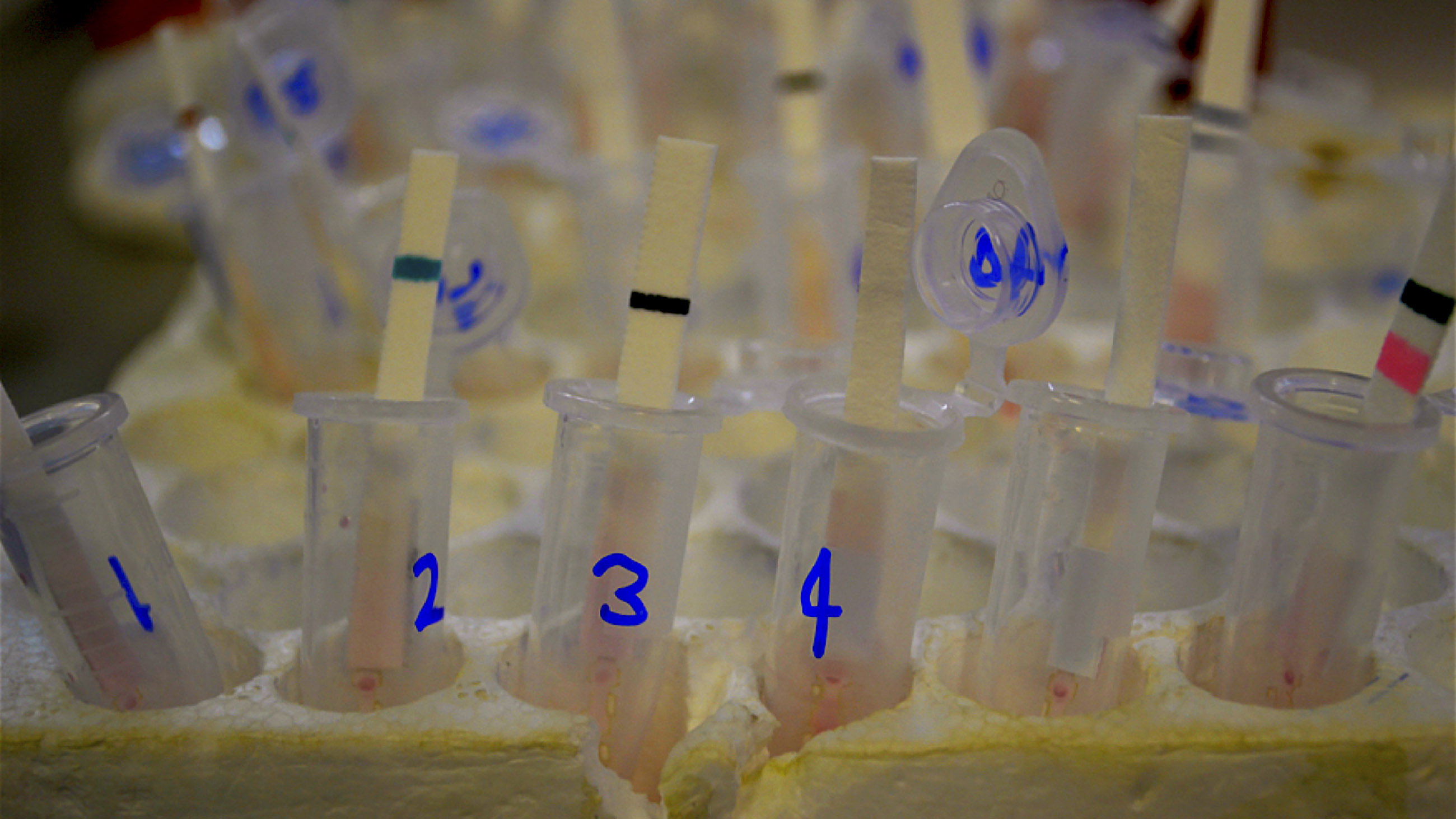

If the samples couldn’t come to Bosch, she was happy to come to the samples. Two days into the fractious workshop, Dr. Ernesto Marques, a member of the Department of Virology and Experimental Therapeutics at the Aggeu Magalhães Research Center —which is part of Fiocruz — opened his lab to us. It was an oasis amid the chaos: pristine freezers, cold rooms, long benches, and DNA amplifiers.

The challenge of detecting a pathogen — in this case, a virus — is the relatively small window of opportunity when it is present in the blood. In dengue, we know that this window aligns with the presentation of fever in patients, lasting for about five days. With Zika, on the other hand, we have yet to understand the precise timeframe.

Bosch explained that there are precious few viral features that can be targeted for detection and diagnosis here. The RNA or genome is one. The proteins that form the virus, the envelopes of proteins that sit just outside the virus, and the proteins that are shredded by the infected cells are others. In flaviviruses — the family of viruses to which dengue and Zika belong — the viral protein called nonstructural 1, or NS1, is secreted, and this is what Bosch’s paper test looks for. The benefit is that it has the potential to detect a viral infection in under 30 minutes, at the very onset of symptoms.

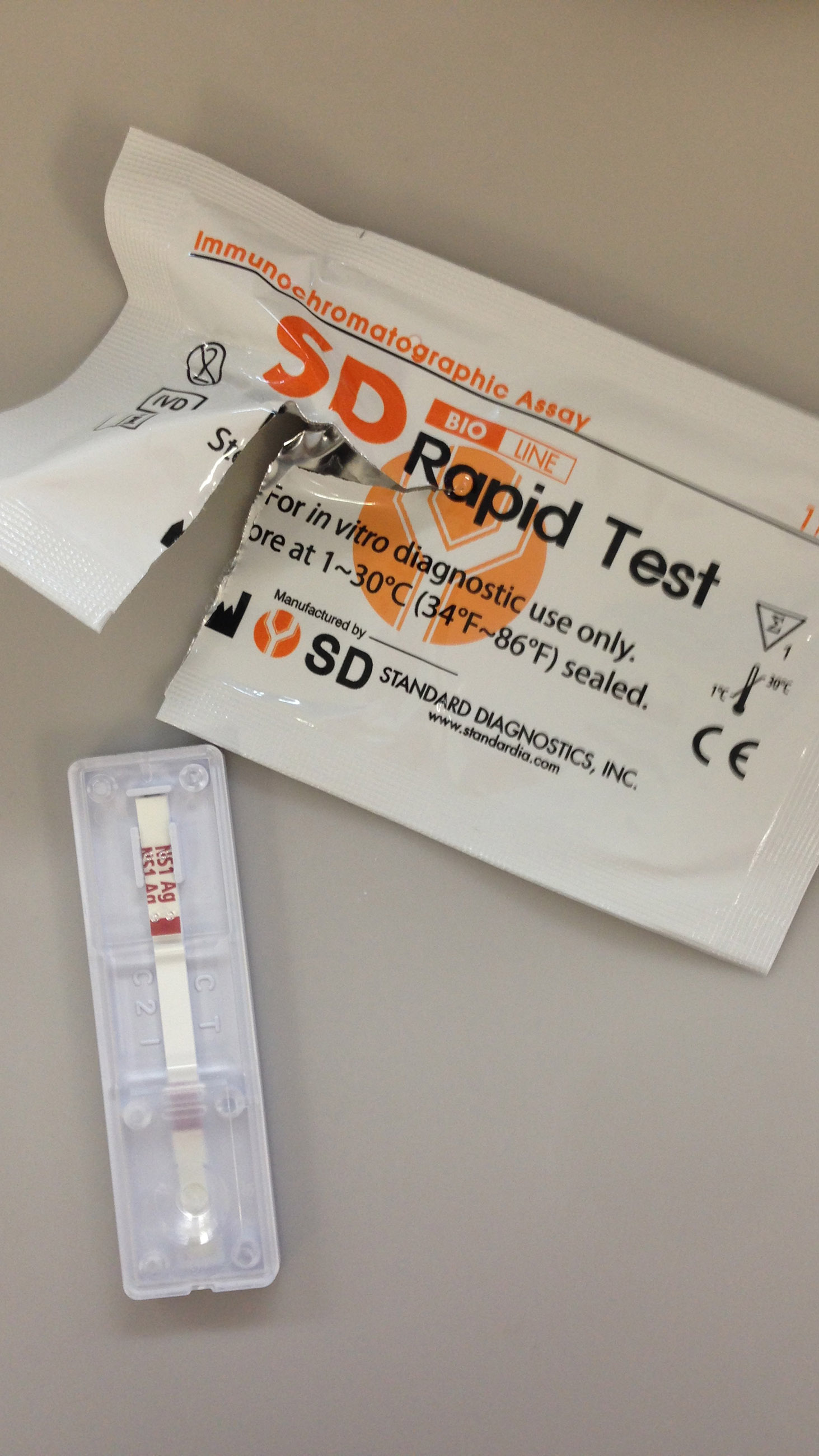

The tool looks a bit like a stick from a pregnancy test, and does not require any machine or reagents at time of deployment — a crucial aspect for testing in more remote areas, because it doesn’t require refrigeration, and is stable for up to a few months. It also only requires a very small drop of blood — a mere a finger prick. Other fluids such as saliva, urine and tears, which have been found to contain Zika virus, can also be used with this technique.

Effective paper-stick tests are already available for other diseases like dengue — indeed, Bosch brought some samples of a rapid dengue test, made by Standard Diagnostics, with her to Brazil. It was telling that some physicians at the hospital in Recife had never seen the equipment before. But the ultimate goal is to build rapid, paper-stick tests that allow two or more viral diseases to be detected in one strip. This could prove crucial in many regions affected by viral outbreaks like Brazil, where co-infections of multiple diseases — dengue, chikungunya, and now Zika — are common.

In Marques’s lab, we were able, for the first time, to test the strips on fresh blood samples known to contain the viruses, including Zika, and the test performed well, though further validation with patient samples is needed, Bosch said.

Efforts like those of the MIT team are unfolding all over the world. At least one rapid diagnosis test for Zika — developed by Canadian biotech firm Biocan — was recently approved for sale in Brazil. But more are desperately needed — and quickly. Having a clear and quick picture of which virus or viruses are affecting which communities can impact whole decision chains, including when and where resources are allocated for controlling an outbreak. This is particularly crucial in remote communities like Ferreira’s, where resources are scarce and patients are often located far away from the nearest medical facility — though of course, this would not have done much for Ferreira’s son João, and therein lies what might be an even more vexing dilemma.

Flummoxed by the outbreak, officials in affected countries like Brazil, Colombia, and El Salvador have been recommending that women delay pregnancies. El Salvador went so far as to recommend that women abide by a two-year restriction, delaying pregnancy at least until 2018. For women who are already pregnant, the World Health Organization recently recommended that in Zika-prone countries, “ultrasound should be performed to identify, monitor, or exclude brain abnormalities in [the] fetus, especially microcephaly.”

The WHO also recommended that pregnant women be offered first-trimester ultrasounds to identify any brain abnormalities.

Of course, with abortions being illegal in most of these affected countries, early knowledge of microcephaly in the unborn would be of little use. And while increasing access to ultrasound technology early in pregnancy sounds like a good idea, most cases of microcephaly are not discovered until the final trimester. Ferreira’s own ultrasound showed no problems for little João Artur.

And so the chaos continues.

As of last month, Brazilian officials were reporting over 91,000 suspected Zika infections. This includes 7,500 pregnant women, roughly 3,000 of who were confirmed to have the disease.

So far, 1,326 cases of microcephaly have been confirmed in Brazil.

Brena F. Sena earned a masters degree in Public Health from the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York. She is currently based in Santiago, Chile, where she works as a researcher and writer for Business News Americas covering energy and infrastructure projects in Latin America.