Can a Blood Test Diagnose a Concussion?

Today, the deadly neurodegenerative disorder chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which the National Football League recently admitted its players may be prone to, can only be diagnosed with an autopsy. But new tests, which look for evidence of brain trauma by measuring proteins in the blood, could help doctors spot problems sooner.

One test, being developed by Boston University’s Alzheimer’s Disease and C.T.E. Center, is looking for signatures of Tau proteins, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s that has also been linked to C.T.E. Another research group, led by Linda Papa at Orlando Health — using a test developed by Banyan Biomarkers — focuses on traces of the proteins GFAP and UCH-L1, which they say are visible in the blood within an hour of brain injury.

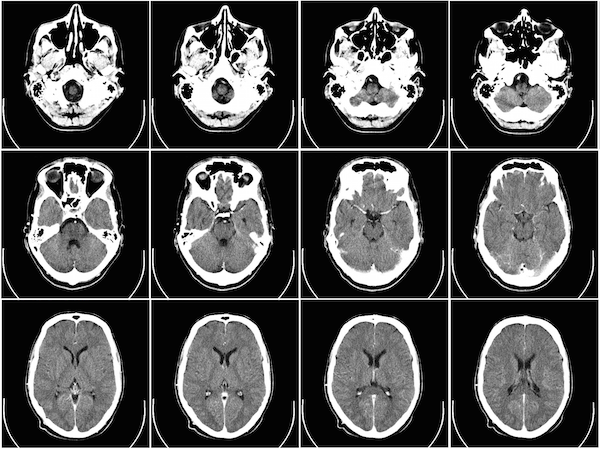

A computed tomography (CT) scan of a human brain.

It all sounds promising, but several hurdles remain.

Currently, concussions are diagnosed using a battery of cognitive tests that grade concussion symptoms along a scale. How quickly physicians would adopt a new blood test for concussions depends on the quantity and rigor of the data supporting it. “Physicians want to make sure there’s the right evidence,” Papa said. “So more studies are coming to further validate these markers.”

A test like Papa’s, while potentially helpful, would require a lot more baseline data to be clinically useful, said Lamont Cavanagh, director of the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine’s Center for Exercise and Sports Medicine. Without baseline data on biomarkers unique to the athlete being tested, for example, how would a physician know when abnormal protein levels have subsided?

Another potential problem facing concussion blood test development is the blood-brain barrier itself, which separates and regulates the movement of materials between the brain and the circulatory system. The precise mechanics of the blood-brain barrier’s permeability is still debated, particularly as it relates to inflammation, age and brain injury — and so the question remains: Can proteins associated with brain injury really pass through the blood-brain barrier and be detected in a blood test?

“No one’s actually seen them pass through,” said Papa. “We can’t say for sure that that’s what they’re doing. We suspect that there’s some jostling of the brain and a disruption of the blood-brain barrier.”

Researchers like Papa are seeing elevated protein levels in the blood after brain injury. In a study of 584 patients published last month in the journal JAMA Neurology, Papa detected GFAP over seven days and UCH-L1 within hours after brain injury.

But how to ensure that those elevated protein levels are a consequence of a concussion? Indeed, blood tests like Papa’s are predicated on the notion that the presence of proteins like GFAP and UCH-L1 indicate a brain injury. But there could be other explanations for these circulating proteins. Researchers have linked GFAP to intracerebral hemorrhages and glioblastomas, tumors of the brain and spinal cord, for example.

With evidence mounting that repetitive concussions can lead to neurodegenerative disorders like C.T.E., a rapid blood test for brain injuries would help sideline concussed athletes – or return those cleared of symptoms to the playing field. But clearly more work is needed before the quick, surefire test that everyone wants is available.

“We’re a microwave society,” Cavanagh said. “The public wants a test that says ‘do I have it or don’t I have [a concussion]?’ But we’re not at a point where we have something that gives us that answer.”