Medicine’s Ongoing Race Problem

Last month, students at Harvard Medical School donned their white coats and took to Harvard Yard to protest the lack of diversity on campus. Echoing racially charged protests on campuses across the country, the “White Coats for Black Lives” movement, as the students called themselves, also has roots in the singularly racist history of medicine — a profession so prejudiced and segregated that, in 2008, the American Medical Association issued an apology for discriminating against black physicians.

As noted last week in a joint effort by Vice and MedPage Today, the situation remains discouraging:

According to the latest data from the US Census Bureau, 62.1 percent of the US population is white, 17.4 percent is Hispanic, 13.2 percent is black, and 5.4 percent is Asian. Meanwhile, 60.1 percent of students entering med school between the 2013-14 academic year and the 2015-16 academic year have been white, 22 percent Asian, 9.8 percent Hispanic, and 7.5 percent black, according to the latest data from [the American Association of Medical Colleges], which runs the MCAT, the standardized test that aspiring physicians (MDs and DOs) must take to get into med school.

One wonders what African American medical pioneers like Vivien Thomas would have made of all this. A brilliant and dexterous African American surgeon, Thomas helped to develop — at Johns Hopkins University — a procedure considered by many to be the beginning of modern cardiac surgery. That was no easy feat, given that Johns Hopkins had a history of exclusion, and Thomas — unable to pay for medical medical school and paid a janitor’s wages — was a self-taught lab assistant to a white surgeon.

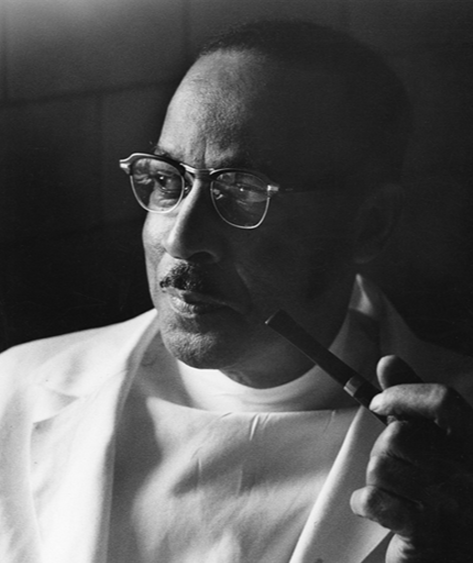

Vivien Thomas overcame financial hardships and institutional racism to become a medical pioneer. So why are African Americans still underrepresented in the medical field? Visual: NIH

“Places like Johns Hopkins wouldn’t even allow black physicians to check their patients there,” says Samuel Roberts, an associate professor of history and public health at the Columbia University. “Hopkins was particularly notorious, but if you look at any white-run hospital in the south, including major research institutions, the only way they were seeing middle-class black patients was if they were checked in by a white doctor.”

It was Alfred Blalock whom history first credited with the new cardiac procedure, which was used to help children born with a heart defect that pumped their blood past their lungs, depriving them of oxygen and leaving them cyanotic. Dividing the subclavian artery, and reconnecting it to the pulmonary artery, allowed the infants to oxygenate their blood through the lungs.

But it was Thomas who had first created the maneuver, which he perfected by working on laboratory dogs. Without a medical degree, Thomas was unable to perform surgery on humans, but Blalock channeled Thomas’s insights in the operating room.

As Katie McCabe described it in a 1998 Washingtonian article, written several years after Thomas’ death, “Blalock insisted Thomas stand at his elbow, on a step stool where he could see what Blalock was doing. After all, Thomas had done the procedure dozens of times; Blalock only once, as Vivien’s assistant.”

The title of the third and final chapter of Vivien Thomas’ autobiography, “Partners of the Heart,” is called “Recognition,” and it’s true that at the end of his life he finally received credit for his work. The Johns Hopkins Medical School awarded him an honorary degree in 1976, and the Moorehouse School of Medicine‘s summer research program now bears his name.

But Thomas remains not just an example of the gap that often exists between skills and access — especially in the medical industry — but also an enduring symbol of the ongoing challenges facing African Americans entering the medical field. As noted by ProPublica at the time, the AMA’s 2008 apology was driven in part by a paper published in the organization’s journal, which, “among other things, detailed how the AMA worked to close down African-American medical schools.”

More recently, data have suggested that despite growing diversity in medical schools in the United States, African Americans — particularly black men — still remain severely underrepresented. Last year, the American Association of Medical Colleges released a report showing that the number of black men applying to medical school had actually seen a 5 percent decline over the last three decades. The number of black male enrollees in medical schools dropped a similar extent.

In a separate survey conducted by the association, 18 percent of black high school sophomores in 2002 wanted to become a doctor. But by 2012, only a fraction of the application pool identified as black.

Roberts believes the problem is, at least in part, an issue of campus culture.

“In every school you’ll find students of all colors who are alienated by ‘Intro to Biochem’ and the kind of entry-level washout courses,” he says. “But when you combine that with the kind of culture that’s alienating black and Latino students on campus, what we have is really high numbers of qualified students leaving a career before they begin it.”

The AAMC itself isolated several factors, including one that helped to hold Viven Thomas back: The considerable financial hurdle of paying for medical school.

But in interviews the organization conducted with African American physicians, the doctors often described a bigger problem — namely, the lack of “champions, peer support [and] mentors” who looked like them. Indeed, in 2013 the AAMC found that there were nearly 140,000 people listed as faculty members at American medical schools.

Fewer than 3 percent of them were black.