How Scientists Can Win the War on Science

The scientific community has been having a lively debate about the so-called “war on science,” including its causes and, indeed, whether or not it is really a war at all. The political class — never one to pass up a good war metaphor — has been happy to contribute to the discussion. Democrats bash Republicans for “anti-science” stances on issues from climate change to contraception to gun control, while conservative pundits counter by crying hypocrisy when liberals are down on biotech and nuclear power.

These are heated disputes, for sure, but calling them a “war on science” is imprecise. After all, the reason science is drawn into these fights in the first place is that advocates want to be seen as having science on their side. Instead, it’s better to think of science as a front in many ongoing battles. And while these battles can make researchers and entire disciplines of science feel like collateral damage, scientists also have to come to terms with the fact that they can’t stop them from happening.

What they can do instead is engage more effectively. Increasingly, doing so requires approaching public communication not from the classic position of experts delivering pronouncements from on high, but as citizen-scientists who can partner with people on the ground in democratic dialogues.

Effective engagement first requires scientists to clearly survey the nature of the battle lines passing over their fields. They should understand that most attacks on research are rooted in political ideology, not antipathy toward science or the scientific method. Dark money funding for various front groups, including ones that attack science and support biased research, have confused the public. Our media environment is also more fragmented and noisy than ever, so it’s harder for audiences to verify scientific claims and counter-claims. As a result, many people’s trust in big institutions, including scientific ones, has grown weaker.

Second, scientists should recognize that the public doesn’t view their profession as monolithic. Indeed, scientific research itself is often the product of competing societal choices. Sociology professor Aaron McCright, for instance, has drawn distinctions between so-called “production science” – which makes new medicine, chemical compounds, food products, energy sources and, arguably, weapons of war – and “impact science,” which focuses on what’s happening to our health, our air, our water, and the world’s built and natural environments.

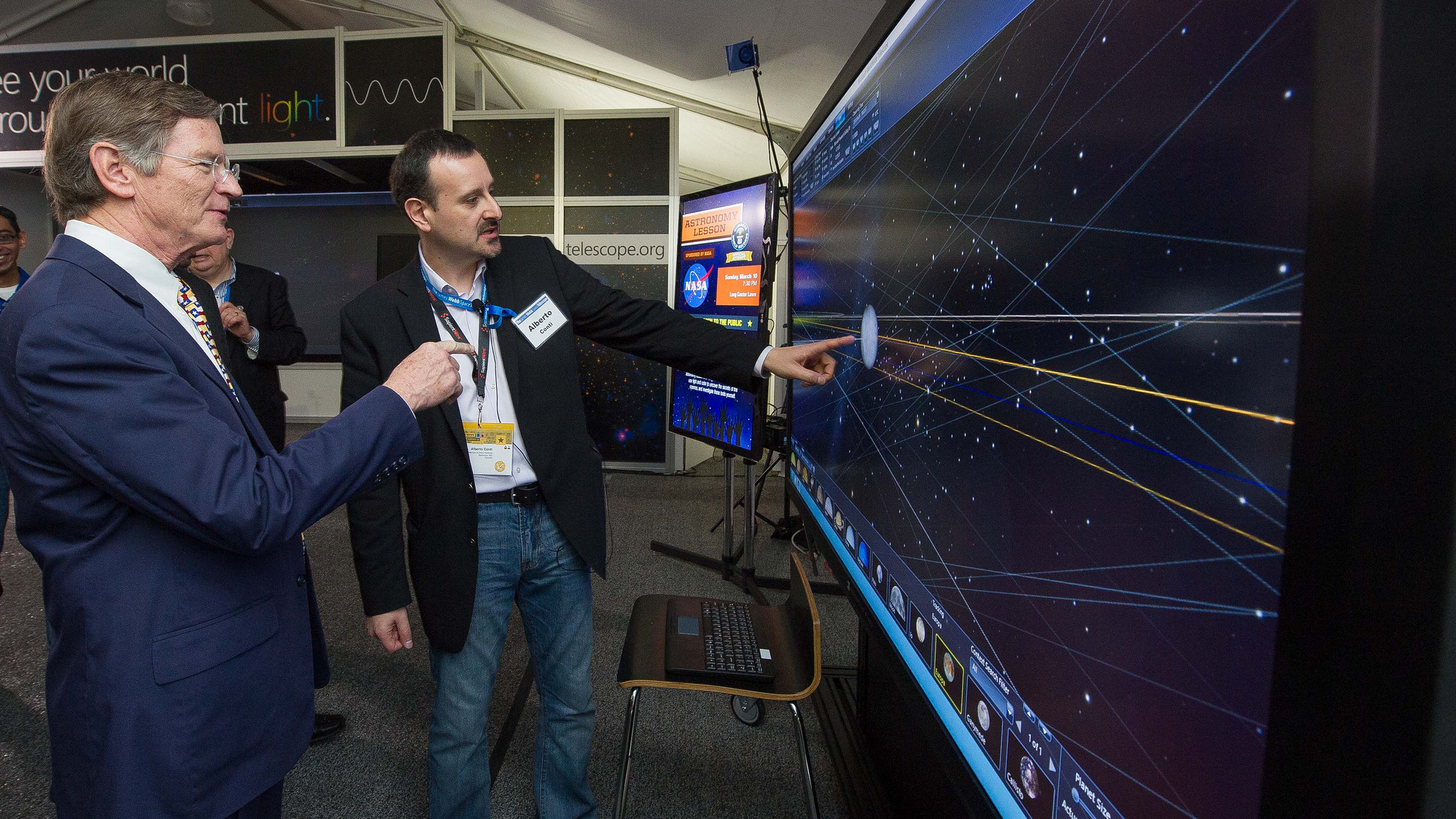

These distinctions help explain how a policymaker like Rep. Lamar Smith, a Texas Republican and chairman of the House science committee, can be bullish on NASA’s James Webb Telescope and asteroid mining, but eager to cut the agency’s climate funding and willing to threaten climate scientists with investigations. They also help explain the roots of science-related disputes in agriculture. Production science, particularly biotech, aims for higher yields, while impact science – spread across ecology, public health and related fields – examines the environmental and public health consequences of a highly concentrated agricultural system.

Third, scientists should approach contentious debates with greater openness about their own opinions. Too often, scientists assume they can “just stick to the science” or that they can approach these issues from an imagined, hyper-objective remove that will meet their colleagues’ approval even if it fails to connect with the public. But as NASA climate researcher Gavin Schmidt has argued, scientists owe it to the public to be transparent, not only about their research, but also regarding what role they think their science, and science generally, should play in public life and making policy, as well as their own values, attitudes and beliefs.

When scientists fail to examine or communicate their own motivations, they can find themselves “swimming upstream” against an array of misleading narratives, to use scientist-turned-filmmaker Randy Olson’s memorable metaphor.

This leads to a fourth step scientists can take: regularly communicating why they do science in the first place. Usually, it’s because they’re curious and because society has collectively decided to support their work.

For scientific professionals working in medicine and healthcare, the life-saving jobs and compassionate motivations are often easier for people to see. Explaining the greater utility of one’s work is usually also easy for scientists at public agencies like the U.S. Geologic Survey. University researchers and private sector scientists often need to dig a bit deeper to explain the value of their work, but they should undertake the effort. After all, their jobs are almost always supported with public funding or tax breaks, too.

Indeed, society is still making very big investments in science. Science historian Mark Largent has argued that scientists should recognize that those investments have instilled them with great power, even when they feel besieged, and that such power comes with concordant responsibilities. Penn State climate researcher Michael Mann has similarly argued that scientists have a basic moral obligation to speak up when their research is of public import.

The good news is that despite all these battles, people still place great trust in science. But scientists still must constantly earn and re-earn that trust. It’s not enough to simply assert one’s authority as a scientific expert. Instead, scientists have to be more personal, more open and more empathetic with their audiences.

Doing so doesn’t make them less serious scientists; it just makes them stronger communicators. Younger researchers – most of them digital natives – intuitively grasp the need to open up science communication. They’re urging their institutions to “evolve along with us” and break down the barriers between the rest of society that scientists have erected over the decades.

We need to listen to them. They’ve grown up in the middle of the political battles too, and they also see the need, greater than ever, for scientists to fully embrace their role as citizens.

Aaron Huertas is a science communications professional living in Washington, DC. He serves as a Senior Washington Director at Cater Communications, a bipartisan strategic communication firm, and he has worked previously for the Union of Concerned Scientists. In these and other capacities, he has worked closely with some of the scientists named in this essay. The opinions above are his own.