The App Will See You Now

For decades, David Kupfer, the University of Pittsburgh psychiatrist who headed the task force behind the DSM-5 — the latest edition of the mental health diagnostic bible — has been a man on a mission. His goal: to make sure that psychiatry gets the same respect as other fields of medicine.

A key obstacle has been the lack of objective measures for psychological distress. Even in the early 21st century, psychotherapists rely on ancient tools — gut instinct, patient self-reporting, and paper-and-pencil questionnaires — all of which are highly subjective, if not inaccurate.

Back in the 1970s, Kupfer tried various methods to collect objective data on patients. In one series of studies, he put activity monitors on their wrists, but had to abandon the research because it proved inconclusive. Today, he believes he has finally found the game-changer he’s been looking for in mobile technology. Smartphones, after all, can provide unique insights into our social lives, including how often we typically call or text with other people, or how regularly we get out of the house. Abrupt changes in those patterns can signal many things, the thinking goes, including possible depression.

“Smartphones can easily provide continuous measures of a patient’s mood and behavior,” said Kupfer, who recently became the medical director of HealthRhythms, a startup that aims to help hospital systems, insurance and drug companies use technology to improve mental health care. Based in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the company is just one of several startups focusing on mental health care to emerge in the last few years. Among the many players: Ginger.io of San Francisco, Boston-based Cogito, and SelfEcho of Santa Barbara, California.

But while venture capitalists see unlimited growth potential in these tech companies, some psychiatrists warn about potential pitfalls.

One major problem is that the apps have rarely been subjected to rigorous scientific testing by independent experts. The American Psychiatric Association has taken a wait-and-see approach; its committee on mental health information technology has begun carefully studying the apps — as have numerous other researchers with clinical trials underway. Some experts also worry that patient data sent to third parties could be misused.

“We can’t forget privacy concerns,” said the APA committee’s chair, psychiatrist Steve Daviss. “While the idea of automatically giving clinicians information from cellphone data is good, it’s also a little Big Brotherish.”

Still, such caveats have not deterred other big-name psychiatrists from jumping onto the tech bandwagon. Last fall, one of the nation’s top research psychiatrists, Thomas Insel, stepped down after 13 years as director of the National Institute of Mental Health to join the Google Life Sciences Team—which was renamed Verily in December.

“Technology can have a greater impact on mental health care than on heart disease, diabetes, cancer or other diseases,” Insel said at a Chicago conference in October, just before his move. “It could transform this area in the next five years.”

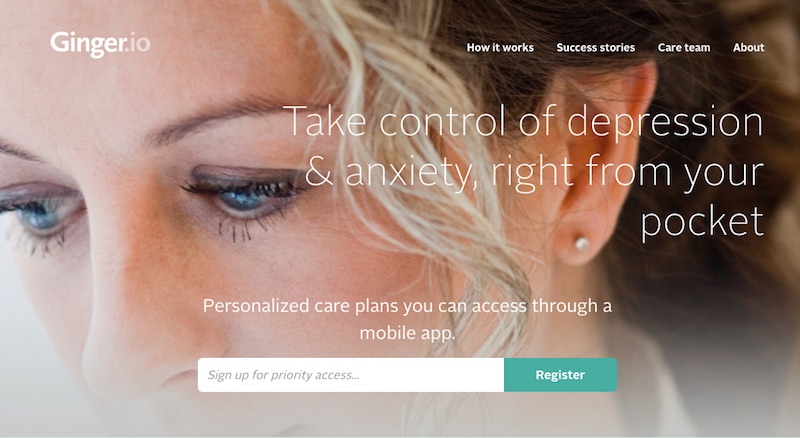

The first startup out of the gate, Ginger.io, was founded in 2011. Named a “2015 Technology Pioneer” by the World Economic Forum, the San Francisco-based company is the industry leader. It has supplied a mobile app to 40 leading health care companies — including insurers and hospital systems — that has already screened 750,000 patients for common mental disorders such as depression and anxiety. And this year it is becoming a full-fledged mental health provider: Having met the licensing requirements in California and several other states, the company will soon be offering clinical care directly to patients.

“We are no longer just providing an electric motor for traditional car companies,” said Anmol Madan, Ginger.io’s co-founder and CEO. “We are building the full Tesla.”

David Kupfer’s company, HealthRhythms, has developed an app called MoodRhythm that relies on smartphone data such as location, distance traveled, movement and conversation frequency to help clinicians assess the emotional stability of patients with bipolar disorder. The app is based on the tenets of interpersonal social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), a scientifically validated treatment for the illness, which shows that improvements in “social rhythms” — more consistent patterns of eating, sleeping, moving and interacting with others — are critical to avoiding relapses.

IPSRT is the brainchild of Ellen Frank, a psychiatrist and longtime colleague of Kupfer’s at the University of Pittsburgh, who is the company’s chief scientific officer. A study to be published this spring in The Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association shows that the app is just as effective in capturing a patient’s social rhythms as a commonly used paper-and-pencil test.

“One big advantage of the app is that it is invisible and does not require the patient to do anything,” said Tanzeem Choudhury, Health Rhythms’ chief technology officer.

This spring, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire will begin using another of the company’s apps — ImagineCare — to track the depressive symptoms of about 10,000 patients with chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension.

Cogito, a Boston-based software company, has developed an app called Companion that can screen for common problems like depression. The app analyzes everyday cellphone use and tone of voice from brief statements the patient enters into a daily audio diary.

In early 2015, Cogito won a three-year $1.8 million Small Business Innovation Research grant from the NIMH to test the app’s efficacy in a group of patients at a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital who suffer from co-morbid medical and psychiatric conditions. Then in December, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs contracted with Cogito to use its app to improve mental health outreach.

The information gathered from Cogito Companion will be relayed back to the patients and their caregivers, who can then discuss if further treatment is warranted. According to Steve Kraus, Cogito’s vice president of marketing, the program will track about 11,000 potentially at-risk vets, starting this September.

“We hope the app will become a crucial tool in the VA’s attempt to prevent suicide,” he said.

The VA already has a division of mobile mental health services, whose director, psychologist Julia Hoffman, developed a free mobile app called PTSD Coach that has been downloaded nearly 100,000 times in 74 countries since 2011. The app includes explanatory material about post-traumatic stress disorder and a self-assessment test to help vets figure out whether they might need professional help. Other features include links to treatment options, both at the VA and elsewhere, and tools like brief meditations and guided breathing exercises to help manage daily frustrations.

PTSD Coach has chipped away at the stigma surrounding mental health problems in the military, Hoffman said, adding, “As one vet told me, ‘PTSD is real. It’s got an app.’” She stresses that the app is unable to provide a formal diagnosis and is not a substitute for face-to-face therapy.

But she notes that PTSD Coach can be useful even for severely traumatized vets who need extensive treatment.

“It can sometimes both reduce the length of therapy and change the nature of the sessions by enabling clinicians to function at the top of their license,” she said. “Since we no longer need to spend time doing psycho-education, we can focus on the more demanding therapeutic work.”

SelfEcho, a company in Santa Barbara, California, has rolled out two products — Mobile Therapy, a web-based platform that relays information on patients’ mental health to clinicians and researchers, and UpJoy.org, an employee-wellness website. Mobile Therapy relies on both active data — provided by patient self-report — and passive data gathered from cellphone use. Using Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, a research tool developed by psychologist James Pennebaker of the University of Texas Austin, who is on the company’s scientific advisory board, Mobile Therapy relies heavily on an analysis of the emotional content of the user’s linguistic activity — such as Facebook posts and outbound emails.

“This textual analysis can help us provide a comprehensive view of psychological health,” says SelfEcho’s CEO, Jacques Habra. Developed with the assistance of Harvard psychology professor Daniel Gilbert, who is also a scientific adviser, UpJoy.org, now used by 150 Fortune 500 companies, offers short, entertaining videos — of, say, playful kittens or sports heroes — meant to help employees lift their mood during work breaks.

To make the transition from a tech company to a mental health provider, Ginger.io has recently hired about 40 coaches, with whom patients can talk or text. The coach is a case manager, functioning as an intermediary between the patient and a licensed therapist or psychiatrist, who can be reached via video chat. The company’s app, which automatically updates the coach on the patient’s well-being, also features a suite of self-care tools.

“We offer on-demand convenience,” said Madan, the CEO, who began studying sensory data at the MIT Media Lab, where he completed his Ph.D. under the noted scientist Alex Pentland. “The 50-minute hour is not ideally suited to today’s world; we can help people with how they are feeling in the moment.”

As chair of the American Psychiatric Association’s committee on mental health information technology, Steve Daviss is charged with educating APA members about apps. By the end of this year, the APA will begin posting reviews of apps behind its paywall.

At present, some companies make hard-to-believe claims in their advertising pitches. For example, joyable.com, which addresses social anxiety using the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, insists that 90 percent of its clients experience a decline in symptoms. Likewise, happify.com, though it has a dozen prominent experts from major universities on its scientific advisory board, confidently asserts that 86 percent of its frequent users will get happier within two months.

Daviss’s ultimate goal is to help psychiatrists pass on an accurate assessment of each app’s risks and benefits to patients.

“We will be looking at whether the evidence base supports the information base and whether there is peer-reviewed research behind it,” he said.

But even with companies citing data from peer-reviewed publications, there may still be a need for caution, argues Jukka-Pekka Onnela, a professor in the department of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

In 2013, Onnela won a $1.5 million New Innovator Award from the National Institutes of Health to study mood disorders using cellphone data. In 2015, he launched Beiwe, a smartphone app designed for biomedical researchers that can collect both active and passive data. Onnela, who coined the term “digital phenotyping” to refer to the moment-by-moment quantification of an individual’s behavior using digital devices, has begun collaborating on research projects with several Harvard teaching hospitals such as Massachusetts General and McLean.

While Onnela praises many of the products produced by the various startups, he sees a conflict between commerce and science. When private companies make claims for their apps, he said, “they don’t give the raw data” ⎯ just summaries of proprietary data. “In order for the field to grow, researchers need to be able to replicate studies,” he went on. “This lack of transparency is an obstacle which must eventually be addressed.”

Joshua C. Kendall’s work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, Psychology Today and BusinessWeek, among other publications.