Keiko Yamaguchi’s troubles began with diarrhea. After a few weeks, her toes went numb. The numbness and weakness crept up her legs, to her hips, and her vision began to fail. That was in early 1967. By the end of 1968, Yamaguchi, just 22 years old, was blind and paralyzed from the waist down.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, Jeanne Lenzer shares a story that was left out of her new book, “The Danger Within Us: America’s Untested, Unregulated Medical Device Industry and One Man’s Battle to Survive It,” being published this week by Little, Brown.

She was one of more than 11,000 people in Japan, (with reported cases also occurring in Great Britain, Sweden, Mexico, India, Australia, and several other nations) who were struck by a mysterious epidemic between 1955 and 1970. The outbreak was concentrated in Japan where an estimated 900 died of the disease, which doctors eventually named SMON, for subacute myelo-optic neuropathy — myelo from the Greek word referring to the spinal cord; optic referring to vision; and neuropathy indicating a disease of the nerves.

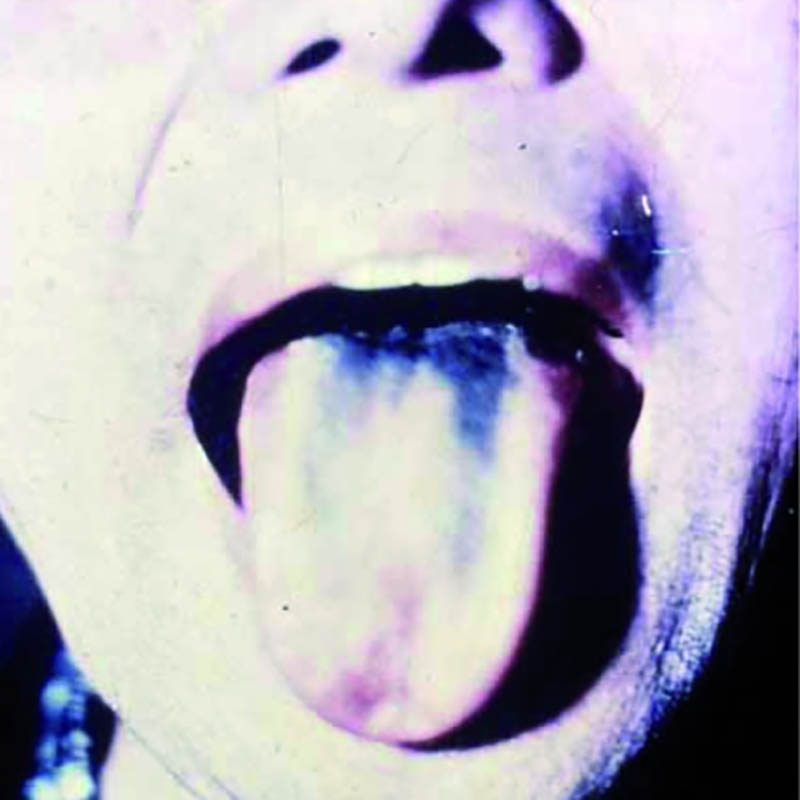

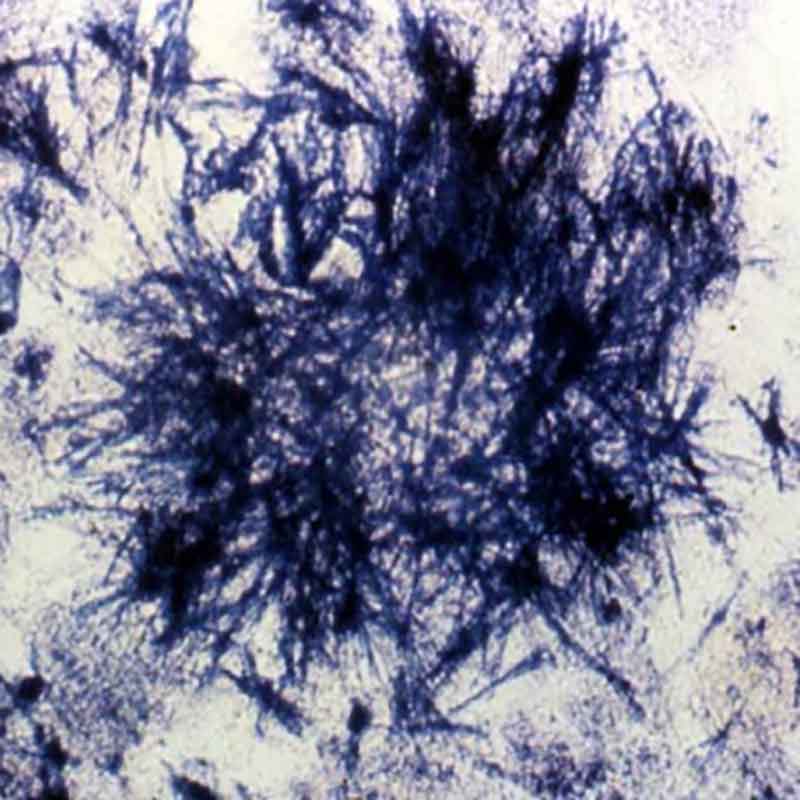

The illness usually started with bouts of diarrhea and vomiting. Some patients, like Yamaguchi, became paralyzed and blind. (My efforts to track her down have been unsuccessful.) An uncertain number developed “green hairy tongue”: Their tongues sprouted what looked like tiny green hairs. Some of the afflicted developed green urine. Family members, too, came down with the disease, as did doctors and nurses who treated it. Approximately 5 to 10 percent of SMON patients died.

What was causing the outbreak? During the 1960s, Japan — where SMON was concentrated — launched vigorous research efforts to find out. Doctors thought an answer was at hand when a researcher studying SMON patients announced that he’d isolated the echovirus, which is known to cause intestinal problems. But soon other viruses were found in patients, including Coxsackie and a herpes virus. The herpes finding was compelling, since those viruses are known to affect the nervous system. But one by one, each claim was disproved when independent researchers were unable to replicate earlier laboratory findings.

Other possible causes were considered and shot down. No drinking water pathogen was detected. Pesticides? That hypothesis was discarded when a study found that farmers, who would have the greatest exposure, had lower rates of SMON than non-farmers. There was some excitement when researchers found that many victims had taken two types of antibiotics, but it seemed unlikely that two different antibiotics would both suddenly cause the same highly unusual disease. Besides, experts noted, some patients took the antibiotics only after developing symptoms of SMON.

Then, in late 1970, three years after the drug theory was dismissed, a pharmacologist made a forehead-slapping discovery. The two presumably different antibiotics, it turned out, were simply different brand names for clioquinol, a drug used to treat amoebic dysentery. The green hairy tongue and green urine, it turned out, had been caused by the breakdown of clioquinol in the patients’ systems. One month after the discovery, Japan banned clioquinol, and the SMON epidemic — one of the largest drug disasters in history — came to an abrupt end.

It appeared that the epidemic was concentrated in Japan in part because the drug was routinely used not just for dysentery, but to prevent traveler’s diarrhea and various forms of abdominal upset; and in part because Japanese doctors prescribed the drug at far higher doses and for longer periods than was customary in other countries.

The illusion that SMON was an infectious disease was compelling: When patients with abdominal upset or diarrhea were treated with clioquinol and developed SMON, family members, doctors, and nurses often took the drug thinking it would protect them — inadvertently creating the very disease they feared. The resulting cluster outbreaks made SMON look like an infectious disease. In short, what people thought was a cure for SMON was in fact its cause.

Few doctors know the story of SMON, and perhaps even fewer use the catchphrase “cure as cause.” Yet the phenomenon is more relevant today than ever. A study published last year suggests that medical interventions, including problems with prescribed drugs and implanted medical devices — from cardiac stents to artificial hips and birth control devices — are now the third leading cause of death in the U.S.

Examples abound in virtually every specialty, from cardiology to psychiatry to cancer care. Jerome Hoffman, an emeritus professor of medicine at UCLA, says it isn’t surprising: Because drugs and medical devices target disordered body systems, it’s all too easy to overshoot and make the disorder worse.

In the 1980s and 1990s, for instance, patients were widely treated with heart rhythm drugs to prevent the abnormal heartbeats called premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) from triggering deadly ventricular fibrillation. The drugs were quite good at reducing the abnormal beats, and doctors prescribed them widely, believing they were saving lives. But in 1989, the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial, or CAST, sponsored by the National Institutes of Health, demonstrated that although the drugs effectively suppressed PVCs, when they did occur they were much more likely to trigger deadly rhythms. Treated patients were 3.6 times as likely to die as patients given a placebo. The drugs could fix the PVCs but kill the patient; as the old joke goes, the operation was a success but the patient died. The problem was invisible for more than a decade because doctors assumed that when a patient died suddenly it was from the underlying heart condition — not the treatment they prescribed.

In another case of cure as cause, a landmark study of Prozac to treat adolescent depression found that it increased overall suicidality — the very outcome it is intended to prevent. In the study, 15 percent of depressed adolescents treated with Prozac became suicidal, versus 6 percent treated with psychotherapy, and 11 percent treated with placebo. These numbers were not made obvious by Eli Lilly, the manufacturer, or the lead researcher who claimed that Prozac was “the big winner” in the treatment of depressed teens. Doctors, unaware that the drug could increase suicidality, often increased the dosage when teens became more depressed in treatment, thinking the underlying depression — not the drug — was at fault. Studies of other drugs in the same class as Prozac, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, have shown similar problems.

There are many other instances of cure as cause: cardiac stents that caused clots in the coronary arteries; implanted pacemaker-defibrillators that misfired or failed to fire, causing deadly heart rhythms; and vagus nerve stimulators to treat seizures that instead have led to increased seizures.

One of SMON’s lessons is the danger of perverse financial incentives. Japanese doctors were paid for each prescription they wrote, a practice considered unethical in most peer nations. Doctors in some prefectures in Japan can still sell drugs to their patients. No wonder they prescribed such high doses of clioquinol for prolonged periods.

More than half of doctors in the U.S. receive money or other blandishments from Big Pharma and device manufacturers. The amounts can be stupendous: Some doctors have received tens of millions of dollars to implant certain devices or to promote certain drugs. Such influence takes a toll on the humans exposed to harmful treatments. The nonprofit group Institute for Safe Medication Practices conducted a study to quantify drug harms and concluded that prescribed medicines are “one of the most significant perils to human health resulting from human activity.” With the rise of the medical-industrial complex and its extraordinary profits, industry has a vested interest in blaming bad outcomes on a patient’s underlying disease and not on their own products.

Industry claims often mislead doctors and patients alike. Ciba-Geigy, the main manufacturer of clioquinol, said the drug was safe because it couldn’t be absorbed into the bloodstream from the intestines. Yet legal filings from a lawsuit against the company show that Ciba-Geigy was aware of the drug’s harmful effects for years. As early as 1944, clioquinol’s inventors said the drug should be strictly controlled and limited to 10 to 14 days’ use. In 1965, after a Swiss veterinarian published reports that dogs given clioquinol developed seizures and died, Ciba was content to issue a warning that the drug shouldn’t be given to animals.

In the U.S., pharma’s influence over what doctors and the public believe about drugs and devices has increased by orders of magnitude, as virtually all research is now conducted by industry and genuinely independent research has all but vanished. In 1977, industry sponsorship provided 29 percent of funding for clinical and nonclinical research. Estimates today suggest that figure has increased to around 60 percent. Even most “independent” research, such as that conducted by the National Institutes of Health, is now “partnered” with industry, making our reliance on industry claims nearly complete.

Stemming the tide of medical interventions that do more harm than good will require a deep examination of cure as cause — and a willingness to stop depending on the industry that perversely promotes it.

Jeanne Lenzer is an award-winning medical investigative journalist, a former Knight Science Journalism fellow, and a frequent contributor to the international medical journal The BMJ.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Prozac and the other serotonin uptake inhibitors are interesting. The author is correct that fluoxetine was demonstrated to increase suicidal thoughts, but not suicides. Several areas in the US saw large drops in prescribing of the serotonin uptake inhibitors (SUI is accurate, SSRI is Pharma hype) as did the Netherlands. And there was a corresponding large increase in teen suicides. Ooooooops!

Talking about suicidal thoughts is good. Suppressing such thoughts is bad. I wish that I could find the papa ER, but about 1990 a study was done that compared Ph.D. Psychologists and M.D. psychiatrists with high school seniors as the control group. They were given admission papers for 100 consecutive adult patients to a psychiatric hospital and asked to pick out the patients who subsequently committed an act of violence against staff or other patients. The three groups picked out the same admits and were all wrong—so much for all that time spent training. Patients who voiced that they felt like hurting someone were picked out. The ones who did act violently were the ones who had committed an act of violence prior to admit, but denied any feelings of violence or aggression. Expression of thoughts and ideations is good. Not understanding this cost many lives.

15 years ago after a prostate biopsy(negative) I came down with the Flu and days later severe prostatitis. My urologist proscribed a long course of the antibiotic Cipro. Weeks later my feet developed intense pain in the arch and heel bone (calcaneus), diagnosed as plantar fasciitis, which I had never had before. The foot pain vanished immediately as soon as I finished taking the Cipro and has never recurred. A rugged friend suddenly developed an achilles tendon separation putting him in a cast for several months. It turns out he had been taking Cipro for some unrelated but minor condition. I informed CDC that there were 2 cases of probable dangerous musculo-skeletal side effects from Cipro. CDC responded with the comment they had received many reports of musculo-skeletal problems associated with Cipro. I heard nothing further from CDC and Cipro is still widely proscribed, without warnings issued. Trained as an EMT, I strongly suspect wholesale corruption within the American Medical Profession and the Pharmacologic Industry, following the same corrupt developments within American Government.

just FYI – there has been a FDA ‘black box’ warning on Cipro (and the other fluoroquinolone drugs) for many years now. The medical community is well aware of the risk of musculoskeletal issues, particularly tendon rupture.

I too developed plantar fasciitis, ad well as inflamed Achilles’s tendons, while taking Cipro, but did recover after several months. My husband did not fare as well, developing “Ideopathic” Peripheral Neuropathy before he was 30. He is now 47 and on complete disability.

Actual cause of SMON still unknown; viral etiology still under consideration. Ito M, Nishibe Y, Inoue YK (1998). “Isolation of Inoue-Melnick virus from cerebrospinal fluid of patients with epidemic neuropathy in Cuba”. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 122 (6): 520–2. PMID 9625419.

Superb article. I’ve been researching SSRIs for almost 12 years now (fiddaman.blogspot.com) and it’s difficult to single out who is responsible for allowing, nae ignoring the suicidal and homicidal adverse events. Do we blame the drug companies, the medicine regulators or the prescribers?

I was recently at the trial of Stewart Dolin Vs GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Stewart had taken a generic version of Paxil, shortly after which he jumped in front of a train. The jury found for the plaintiff, his wife, who had filed the suit against GSK.

What was remarkable about this trial was the evidence shown (for the first time)

During the Paxil clinical trials, it was learned that 22 adults (over the age of 30) died, 20 of whom died by suicide. All 20 were taking Paxil.

GSK and medicine regulators around the world kept this “in-house”. Years later, GSK and other drug companies, along with the FDA, were forced to include a black box warning on antidepressants that warned of increased suicidality in children and adolescents. Nowhere on the black box does it give the same ‘stringent’ warnings to adults.

I wrote to the British drug regulator (The MHRA) to ask if any children or adolescents had died in Paxil clinical trials. ‘No’ was the answer.

It seems quite bizarre then that an increase in suicidality warning for children and adolescents would be placed on the labels of SSRIs when it’s the adults at risk.

Of course, GSK et al could not warn of an increase in suicidality in adults because this would mean fewer sales. Let’s face it, if the drugs can cause suicidality in adults then it stands to reason that kids could be harmed by it too. So the drug companies and regulators took away a portion of these sales by claiming it was only children and adolescents who were at risk.

So, when I’m asked, “Who do you blame?” the answer isn’t really that simple. I lay a lot of the blame on the regulatory bodies, the MHRA, for example, have an incestuous relationship with GSK. The current CEO of the MHRA is Dr. Ian Hudson who was previously the World Safety Officer at SmithKline Beecham (GSK’s name before the merger). Before him was the then Chairman of the MHRA, Alisdair Breckenridge, he was also an ex-employee of GlaxoSmithKline.

The revolving door that exists between drug companies and medicine regulators is, to be frank, quite nauseating. We will always have drug problems if we continue to allow the fox to guard the henhouse.

When I was young and speed was legal , I was prescribed it by a gynecologist. I took it for about five years before it was outlawed. It caused a lot of problems for me and I had no idea until much later that the drug was causing the problems. Now I won’t take any drug that is new. They have to be more than seven years on the market or not for me. I have no faith in the drug industry or in doctors who love them. After firing many doctors I now have some that are as suspicious of new drugs as I am , at least for me. I get black hives all over my body from Eliquis. White hives from all the statin drugs. And many other side effects from other drugs. Some just make me confused and drunk. I can’t drink alkahol either, I don’t have the enzyme that allows other people to digest it. Three day hangovers from a glass or two of wine with dinner are no fun. I find that aspirin for blood thinning works just fine as long as I eat something with it, and it is a lot cheaper. I have found work arounds for most of my health problems and pain is helped substantially with heat or cold or my vibrating bed. I have terrible asthma and that does require prescription inhalers. So the drug industry does contribute a little to my continuing life.

Fascinating article, can’t wait to start reading your book, and kudos for taking on this topic, and especially, the dangerous device industry. I have way too much experience with “cure as cause” in medicine, and equally if not more, in dentistry. That is worthy of an entire book as well – perhaps an entire encyclopedia (for those who remember what they were), or an entire library.

Could you give any examples of dental mishaps? I think I might have suffered some myself, wanted to compare notes. I had a filling fall out of the same tooth many times- that tooth then required a root canal, crown, then they said they wanted to redo the crown, then they wanted to take it out and put in an implant. WHEW- so much money down the drain!

I used Cpap. I did not have central sleep apnea until several months after starting treatment. I seriously believe the treatment cauzed the CSA . They never list it as a side effect.

The use of a CPAP does not cause sleep apnea. Your claim is false.

Interesting article! In my mid 20’s I had an aweful experience with Sleep Paralysis and began suffering with panic attacks fearing that it could occur again. I was prescribed Prozac and Celexa to treat my anxieties however, the buzz at the time was that the medications could lead to suicidal thoughts. None of which I had ever had as I was a happy positive person who received great support from my family and my boyfriend. I didn’t reveal to anyone that I was prescribed Prozac or Celexa since it was taboo. That would have created a shock value to my family and friends that something was mentally wrong with me. I never took the medication because I had feared that it would spin my mind out of control. So with each panic attack I decided to “cure as cause”(as I now can name it from your article) until to was able to maintain my anxieties. It’s been a quite a long time since my last episode and sometimes it is indeed best to “cure as cause”. Thank you for your eye opening article!

?? That’s not at all what is meant by “cure as cause”.