Iwake up in the coat closet. It’s dark, and crowded. Feeling for a doorknob, I graze coats, boots, and people who seem to be sleeping. But this isn’t a dream. I’m a guest in a foreign place. I open the door and tumble into an open living room: a stonework fireplace on the north wall, a cozy, overstuffed couch. Through windows to the south, a glassy swimming pool, splaying outward to gardens beyond. It would be correct to call this place a mansion in Palo Alto, California. From the looks of it, squatters run it now.

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, Claire L. Evans shares a story that was left out of “Broad Band: The Untold Story of the Women Who Made the Internet” (Portfolio).

I move from room to room, typing directions: go south, go south, go north, go northeast, go west. I type these words into a window of ever-shifting text, before breaking into a run, switching to the faster, shorter commands e, ne, se, w, up, until I reach the master bedroom. I seem to have tripped the burglar alarm in here. It beeps silently in the text — <<< beep >>> <<< beep >>> <<< beep >>> — growing more frequent until it’s interrupting me, butting into my commands.

The burglar alarm is a puzzle, an interactive object programmed to respond to a combination of commands and conditions: In setting it off, I’ve collided into a self-contained sequence of textual events. The beeping fades as I leave, echoing through the halls of the mansion, which is really just a string of code, where people once lived, and still do, in some way or another, as someone must, until the server winks out. The house of LambdaMOO takes some getting used to.

In the summer of 1990, Curtis was a young research scientist at Xerox PARC. At the research lab’s venerable, mirrored hillside campus, he studied compilers and formal semantics; in his free time, like many people with access to a computer in those days, he studied the early internet. He couldn’t get over Usenet Newsgroups — online mailing lists devoted to all the arcana under the sun. He browsed them all by title. Here was one about MUDs, an acronym he’d never seen before. “Probably something really stupid,” he thought, “one of those newsgroups that gets created just because some weirdo out on the net wants some jollies.” Maybe mud wrestling, a “wet dirt appreciation society.”

He joined — even in the early days, the internet was full of subcultures to discover — and quickly learned three things. One, the people on the mailing list were so absorbed in the subject that they felt little need to explain it to outsiders. (Common enough online, even today.) Two, MUD had nothing to do with wet dirt. And finally, whatever it was, “approximately half of the contributors thought it was a game; the other half vehemently and heatedly disagreed.”

MUD stands for Multi-User Dungeon, or Multi-User Domain, and it’s nearly impossible to describe to a modern computer user what that means, because although MUDs once made up 10 percent of internet traffic, their dominance was obliterated by the arrival of the visual, hyperlinked, page-based Web. To anyone weaned on images and clicked connections, every explanation sounds batty: A MUD is a text-based virtual reality. A MUD is a chatroom built by talking. A MUD is Dungeons & Dragons all around the world. A MUD is a map made of words. The science fiction writer Philip K. Dick once defined reality as “that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away,” and in that sense a MUD is a real place. But a MUD is also nothing more than a window of text, scrolling along as users describe and inhabit a place from words.

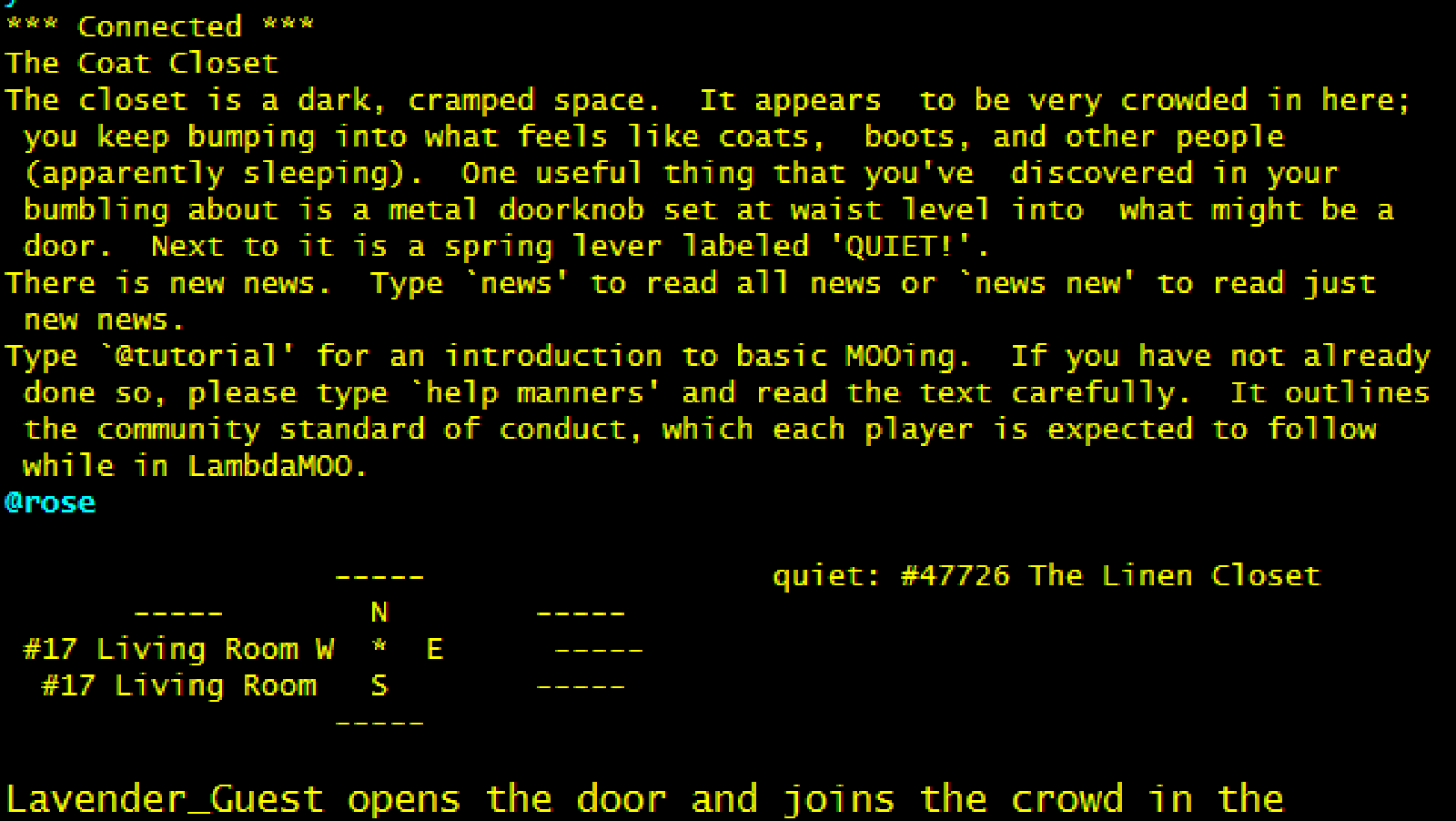

Maybe it’s easier if I demonstrate. Meet me back in the coat closet. The way I have it set up on my computer, the coat closet is in the Terminal (a program through which I connect to the LambdaMOO server in Washington State). When prompted, I type:

Connect Guest

This lets me into the house. On my screen, new text appears:

*** Connected ***

The Coat Closet

The closet is a dark, cramped space. It appears to be very crowded in here; you keep bumping into what feels like coats, boots, and other people (apparently sleeping). One useful thing that you’ve discovered in your bumbling about is a metal doorknob set at waist level into what might be a door.

We were here before. Earlier, when I groped in the darkness for a doorknob, what I really did was type “Open Door,” and immediately below the description of the coat closet appeared a fresh paragraph, titled “The Living Room”:

It is very bright, open, and airy here, with large plate-glass windows looking southward over the pool to the gardens beyond. On the north wall, there is a rough stonework fireplace … .

Nearly every word here contains a description of its own — each summoned by the use of the “examine” command. If I “examine fireplace,” for example, it’ll prompt a list of bric-a-brac left on the mantel by users over the last 20 years: a cuckoo clock, a compass, a crystal bauble, a rumpled photocopy, the key to the Pearly Gates. These, in turn, contain multitudes. Everybody comes through the Coat Closet the first time they visit LambdaMOO, entering the Living Room through a curtain of clothes, like children into Narnia. In between the textual rooms and objects they explore, there’s a faster-moving flow of words, the coursing real-time chatter of LambdaMOO’s other users. This is a Multi-User Domain: a chatroom and a world at once, a place where telling takes the place of being.

As soon as Curtis understood this — what a MUD really was — he was tweaking code, adding to the work of another programmer with a powerful object-oriented model. He set up his own MUD server on his workstation at PARC and called it LambdaMOO, Lambda being a personal nickname and MOO a recursive acronym (something programmers seem particularly to enjoy), short for “MUD, Object-Oriented.”

LambdaMOO was different from the earliest MUDs, which were Tolkienesque fantasies — hack-and-slash games for Dungeons & Dragons types with computer access, mostly college students. LambdaMOO was one of the first social MUDs, where people convened largely to play-act society, and what might have been “one of the first MUDs to be run by an adult,” Curtis believes. Later there would be a postmodern MUD for theory heads, MUDs for kids, a rigorously detailed cyberpunk MUD, a MUD for media studies scholars modeled on an academic conference at the MIT Media Lab, a MUD for thespians, MUDs for Trekkies (of course). These were worlds built, like castles on the cloud, by dedicated users.

The thousands of people to pass through LambdaMOO since Curtis turned on the server have imbued the house with textual life. There are worlds hidden everywhere within the walls. Dive into the pool and you may find yourself exploring a subterranean cavern full of ancient relics; poke a kitchen vent, and you may end up, as I did, lost in the heating ducts. Players may venture into floating bubbles, the coils of the television set, or the Alpine village hidden away in a snow globe sitting on an end table.

Curtis barn-raised all this with a pair of Australian hackers he’d met on a MOO at U.C. Berkeley, hosted on a machine nicknamed “belch.” They modeled it on a place Curtis knew well enough to rebuild from memory: his real-life house, a split-level ranch in Palo Alto he’d once shared with an ex-girlfriend, Judy Anderson. When a writer who had spent the better part of a year living in LambdaMOO visited Curtis’ real house, he couldn’t shake the sensation that it was a copy, not the original. “Things are out of place here,” he wrote, “rearranged, as when a memory from waking life becomes a parody of itself when you’re asleep.” But Anderson felt at home in the virtual house right away.

It was the entrance: LambdaMOO’s front door is an artifact of the house itself, a weak spot where the idiosyncrasies of the real building seep into the code. In the MOO, it takes one step to get from the Living Room to the Kitchen; through the Entrance Hall, it takes three to return. It’s so common a catch tray for newbies that regulars would push guests into the Kitchen as a prank. At the house in Palo Alto, the front door opens onto a similarly illogical hallway. “The north-south entrances don’t really line up, and in the house it really felt that way,” Anderson says, and Curtis concurs: “I swear to God, that’s what it feels like in the real house — the doorways are aligned in just such a way that if you’re sitting in the living room, the kitchen is just not a destination.”

Anderson appreciated the detail, but that was her style. At Stanford, she was tutoring her fellow freshmen on the school’s DEC System 20 mainframe after only three weeks of classes. Before Stanford offered an undergraduate degree in computer science, she studied the philosophy of formal systems and logic. She got online from a shared terminal in her undergraduate computer lab, then from the Stanford AI lab, where she worked as a tape dump operator, and finally from the job at Hewlett-Packard she took before enrolling in Stanford’s new master’s program in computer science. But she met Curtis square dancing.

“There are a lot of nerds who do square dancing,” she assures me. “It’s a formal system.” If you have brains, two left feet are immaterial: each step, called on the fly, is dictated by a set of remarkably — and perhaps blissfully — complicated rules. (Around the same time, the square dance clubs at MIT and Stanford were brimming with computer science people.) “Basic square dancing…is a certain set of about 75 or 80 calls that you have to memorize,” Curtis explains, “and you’re dancing, and it’s fun, and there are rules to it, but it’s relatively straightforward. And then there’s a level where they give you just a little bit more stuff, called Plus, and it gets a little bit more interesting. You say, ‘Oh, that’s kind of neat,’ if you’re an engineer. And then you get a little further into it and discover that no, no, the rabbit hole goes pretty deep. There’s Advanced One and Two, and then there’s Challenge One through Four, and by the time you get to C4, maybe there’s 200 people in the world who dance this level of dancing.”

Challenge square dancing is physical, social, and extraordinarily technical. “The amount of visualization and interpretation of [its] many sometimes interlocking rules has to happen in real time,” Curtis says. It’s not uncommon for an eight-person square to break down, one by one, until only one dancer remains. People who thrive at this level can call up and model complex patterns in their minds while remaining locked in step with a partner who moves diagonally across the square, dancing in mirror-reverse. Curtis and Anderson were both excellent Challenge dancers, stars of the C4 scene at Stanford. They breezed through the levels, memorizing calls and extemporaneous modifications, starting new classes before they’d finished the last, and thought nothing of flying across the country to attend C4 conventions, where they’d dance with actuaries, engineers, computer scientists, and physicians.

Anderson and Curtis bought the place in Palo Alto in 1986, with their friend Ken Olum. “It was a great house,” Curtis remembers. “We had such parties, and such game nights, and square dancing, and crazy experiments.” Roommates cycled through the place, which was, for a time, clothing optional. They delighted in swimming, and made games of walking across the pool cover, but after a few years of festive cohabitation, Anderson announced to Curtis that she and Olum were moving, together, to Massachusetts. In 1988, she sold her share in the house to a friend, who moved in with Curtis and his new partner, another woman he’d met Challenge dancing. But the exes remained friendly, and on business trips back to California, Anderson still crashed at the house. It was on one of these trips, in November 1990, that Curtis showed Anderson the MUD he’d started after their breakup.

Almost immediately, Anderson began to add to Curtis’ code. Working remotely for a software company in California, she spent her waking hours at the computer, building. She finished the master bedroom and added adjoining rooms, the pool, a hot tub — the heart of LambdaMOO social life — a belowground maze, a hairstyling salon, and “Hacker’s Heaven,” a hangout complete with intravenous caffeine drip. To her creations, she brought her C4 dancer’s fascination with spatial puzzles; LambdaMOO’s trickiest programs, including the burglar alarm, are signed with her MOO alias, yduJ. She put a motorcycle in the garage, planted a tree outside, and served as “mom of the MOO” to Lambda’s growing population of users.

When I tell her how I encountered the burglar alarm, Anderson laughs. “There was an alarm system in the house when we bought it,” she says. “We had not yet turned it off … and some guest did something, and the alarm went off. We were dashing about with screwdrivers, trying to figure out how to disable the alarm.” The early internet’s most personable areas often felt that way because they were modeled on known places and personal histories, built by real-life friends, internet buddies, and occasionally ex-lovers. Before LambdaMOO contained the universe, it was a ranch house in California shared by three programmers and their roommates. The virtual version defied physics, but it was still a home, full of memories, faulty alarm system and all.

Curtis hasn’t visited LambdaMOO in nearly 20 years (“You can’t go back,” he muses), but Anderson still logs on. She doesn’t talk to many people anymore, and when we pull up the list of 50-odd active users, she recognizes only a half-dozen names. If she’s not there to meet with friends, I ask, then why does she keep coming back to this empty house? The place is like a museum. Anderson retains some wizardly duties — dispensing new accounts, for example, to tourists like me — but the real reason she stays is that it’s easy. LambdaMOO once exhausted her connection; today, she can leave it open, in the background, a living blueprint of a place she once called home. “I have a window,” she says, simply. “And there it is, with me in it.”

Claire L. Evans is a musician and writer. She is a founding editor of Terraform, VICE’s science fiction vertical, and the singer in the pop group YACHT. ‘Broad Band’ is her first book.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

The evolution of MUDs continues, and a large playerbase still exists. If you read through this and are inclined to the fantasy adventure genre, check out The Carrion Fields (www.carrionfields.com). I started on MUDs in the very early 1990s during middle and high school, and have continued to enjoy them into adulthood. Put it this way- I started mudding at 300 baud, and have witnessed every step up from 1200 to 100M cable internet. Unless it was a huge battle, though, it ended up seeming that 14.4k was plenty. Now you can MUD with a Youtube soundtrack in the background, though.

LambdaMOO was downright modern and late to the scene. This article has a nice tone but it’s largely incorrect when it comes to the history of MU*s.

Who remembers me? ?

Beautiful words.. Wow

I liked it… In particular the part where when you wrote… The closest is dark…. ?

Psychedelics had a great impact on me in the early 1970s only because of psychedelics can I identify with this nonsense

Apparently there’s some controversy of which was the first social mud. Wikipedia refers to TinyMUD (my personal favorite during its short life) as “the first so-called ‘social’ MUD”:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TinyMUD

There’s still a big MU* community, I’ve been playing them since the early 90s and while many of the old ones are gone, there are plenty of active and thriving games.

Gemst9ne IV is a MUD that is still going strong since the late 80s. http://www.play.net/gs4

I lived in MUDs for a long time. I used to play a few on CompuServe. But there is one version that has disappeared…but *could* be brought back if the creator would…

Illusia: Quest of the Eternals was a GMUD (Graphical MUD) which displayed images when looking around. They were static images created and donated by the various Devs (the list changed over time) of the game. It had PvP in areas, vast environments, mazes, etc. It was a great place just to hang out with other players…it had a “social area” were we could just chat together. There were “monster players” and “heroic players” which did battle…if they happened upon each other in the world!

I’ve contacted the Original Creator of the game and tried to cajole him to bring it back. He HAS replied that, while it is doable for PCs, he *could* bring it back as a mobile game…if he could find the time. But he works for a software company now and works long hours. If *only* he could allow others to Bring It Back To Life!!! Hopefully he’ll see this article and resurrect it for us PC users to enjoy again?!

TQQdles™,

Dolnor Numbwit

Eternal Testing Newbie

Member, The Older Gamers (TOG)

Yduj and Pavel..my many many thanks for everything….i still have friend s from lambdas early days 1990s.. would like to see what you look like these days…

Snowlord aka #87010 aka Dexter Craig in TN on fb…

CHEERS!

What a blast from the past… I loved, loved, *loved* LamdaMOO… I used to have out there a lot.. I used the source to Lambda to create my own MOO to model the infrastructure of a very large bank I was a VP at in the 90s… we made network modules so we could monitor and manage bits of the network and infrastructure complete with smart agents and bots to automate a lot of grunt work. Outside of work I used MOOcode and other similarly scripted MUD systems to experiment with VRs, and intelligent agent systems.

I was just describing Lambda to a fiend this past week… the whole experimentation of the mid-late 90s seems like a fleeting dream now… I miss the 90s.

Nicely written article, but it could have done with a lot more research. Lambda was not even close to the first social MUD, and certainly isn’t the oldest still running. Presenting its creators recollections and opinions as fact is misleading at best.

beautifully written. i feel wistful for somewhere i’ve never been.

The paragraph that starts “We were here before” probably shouldn’t have that grey line on the left — since it’s the one part of that section that *isn’t* quoted material.

Thanks, Lou!

That’s a great article. I played in MUDs and MOOs in the 90’s. They were often funny and smart. It’s a peculiar feeling when the things in your personal history become a curiosity to be explained to later generations. Not that MUDs were mainstream entertainment, I was in the computer crowd, but still. I did not however, know about the square dancing / engineer crossover! Fascinating. Thank you, Claire L. Evans. Your band is great too. I have YACHT on a jogging playlist.

MUDs r alive and well. One I’ve played off and on since ‘97 is AOC or Age of Chaos, based off of Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time series. To find out more about the MUD check out http://aocblackbook.com.

If you’re looking to connect goto http://aoc.pandapub.com. See ya there!!!