Once, I thought I was a bear.

For one long night, tethered to medical equipment after a grueling more-than-six-hour cancer surgery performed by a human-robot team, I felt this as a strange and overwhelming certainty. I wasn’t one of the wild bears I’d observed loping through the hills in Yellowstone National Park, or even a bear in a zoo. I was a caged bear held in a bile farm somewhere in Southeast Asia.

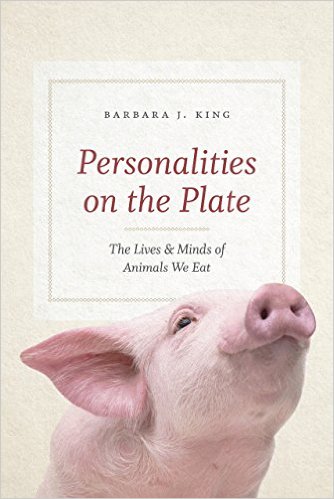

WHAT I LEFT OUT is a recurring feature in which book authors are invited to share anecdotes and narratives that, for whatever reason, did not make it into their final manuscripts. In this installment, Barbara J. King shares a story left out of her new book, “Personalities on the Plate.”

It was May 2013, and for the past few years I had been researching the expression of emotion in animals. Along the way, I had learned about the bile-farm bears and the hard cruelty of how they are kept.

For more than a thousand years, bear bile — produced in the liver, stored in the gallbladder, and extracted from that organ by humans — has played an extensive role in traditional Chinese medicine. Used to treat liver diseases, including cirrhosis and cancer, the bile is also supposed to fight fever and pain, increase libido, and even, according to an article published last year in the journal Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, to stop “endogenous wind.”

The efficacy of many of these treatments is highly debatable, but the suffering caused by the bile extraction process is clear. Originally, the bile was procured by killing wild bears and removing their gallbladders. For about 30 years now, bears — mostly Asian black bears (also called moon bears), but also sun bears and brown bears — have been squeezed into cages on farms, surreal places where they dwell in a nightmarish limbo as their bile is harvested. In 2010, Fiona MacGregor, a reporter for The Telegraph, visited such a farm on the outskirts of Luang Prabang, Laos. There, the bears are “confined in barred enclosures measuring 15 square feet,” she wrote. “Some of the animals cannot stand fully upright and some display the repetitive swaying movements of severe stress. Most also have mange, and scratch incessantly at their patchy fur. Despite the 100F heat outside, there is no water in any of the cages.”

Grimly, MacGregor noted that the Luang Prabang bears were “luckier than others” because “in some bile farms the bears live with a catheter inserted into their gallbladder.” In the 2009 book “Smiling Bears,” Else Poulsen has more to say: “Without proper anesthetic, drugged only half-unconscious, the bear is tied down by ropes, and a metal catheter, which eventually rusts, is permanently stuck through his abdomen into his gallbladder.”

That catheter was the point of connection for my imagined hospital transfiguration. My catheter didn’t hurt, but it caused constant unpleasant pressure. I was also hooked up to cardiac telemetry equipment, and on both legs were boot-like devices that automatically inflated and deflated to reduce the risk of blood clots. My husband and daughter had gone home to sleep; I was alone and feeling gutted, because to some extent I was.

Skillfully working the controls of a da Vinci surgical robot and boring small holes into my abdomen, my oncologist had removed my uterus, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and 29 lymph nodes. A few weeks earlier, a biopsy indicated that serous papillary carcinoma, a rare and aggressive cancer, had invaded my uterine lining. The sequence of my treatment was clear: surgery, three rounds of chemo, 25 sessions of external-beam radiation, three courses of internal radiation via canister inserted into my vagina, and three final rounds of chemo.

In the years since that treatment’s conclusion, I have never spoken of my nighttime bear visitation to anyone but my husband. Profound and at first inexplicable, it was not a fever dream or hallucination, I now believe, but an attack of acute, embodied empathy.

Like us, bears are omnivores, smart and often highly social. In the wild, they show evidence of prodigious learning and memory skills in foraging. Working in a zoo, the psychologists Jennifer Vonk of Oakland University and Michael J. Beran of Georgia State University have demonstrated that black bears have a degree of numerical competence, according to a 2012 study. Vonk and Beran devised a touch-screen experiment in which the bears, using their noses, showed they could distinguish sets of items based on number and surface area.

Our primate brain’s ability to take the perspective of others (our theory of mind) causes us to realize — to feel as well as to know — that bears must experience anguish when their bile is continuously harvested using the methods I have described. Yet the animal studies scholar Lori Gruen cautions in her 2014 book “Entangled Empathy: An Alternative Ethic for Our Relationships With Animals” that empathy is far more complicated than it looks on the surface.

“Entangled empathy involves a particular blend of affect and cognition,” she writes. “The empathizer is always attentive to both similarities and differences between herself and her situation and that of the fellow creature with whom she is empathizing. This alternation between first- and third-person points of view allows us to preserve the sense that we are in relationship and not merged into the same perspective.”

Humans, Gruen says, are in relationship with “many, many animals and we may never have the opportunity to meet them or look into their eyes.” Our connection doesn’t depend on being with them; it exists and is primary. Or as the anthropologist Gregory Bateson put it in his 1972 masterwork, “Steps to an Ecology of Mind,” “The mental world — the mind — the world of information processing — is not limited by the skin.” We are in relationship all the time, everywhere.

So we need to distinguish between the experiences of other creatures and anything we might imagine to be parallel in our own experiences. Unlike the bears, for instance, I was in a safe place as a post-surgical patient. My organs had been removed for my own good; I was surrounded by people caring for me and about me; and my distress was acute, but it was temporary and inflicted without cruelty.

The bears, turned into harvestable commodities year after year and decade after decade without relief, do experience cruelty. Only by focusing on this central difference can we begin to understand and to address what is happening to them.

Claims of human exceptionalism are increasingly unsustainable because evidence from animal behavior lets us see the lives of thinking and feeling animals: Chimpanzees who make tools, hunt, and swing between poles of compassion and lethal aggression; cetaceans who create vibrant learning-based cultures in the ocean; and the savvy, moody invertebrates described by Sy Montgomery in “The Soul of an Octopus.”

Cruelty, though, stands as unique or nearly unique to humans. When lions run down antelopes, orcas hunt and consume whales, or house cats toy with mice, there’s no evidence that they are aware of causing harm to another being. (It’s an open question whether male chimpanzees, capable of taking the perspective of others to at least some degree, might qualify as cruel when they attack other male chimpanzees and twist off limbs, beat and kick their bodies, and rip a testicle clean off the body.)

A lesson of the Asian bear bile farm — in addition to the primary one, that the bears need our attention and our rescue — is that it acts as a pointer to what we may not so readily want to see. Despite intense and often successful rescue efforts by organizations like Animals Asia, bear bile farms still aren’t very widely known. It’s tempting to exoticize them as “Asian,” as something that supposedly civilized Westerners wouldn’t do. But in a very real way, they mirror the factory farms that underpin our food system in North America and the West. Unlike the prolonged suffering of the bears, the crowded, uncomfortable, and wholly unnatural lives of pigs and chickens raised for food are drastically short: They are chemically fattened and slaughtered within months.

“We have the burden and the opportunity,” writes Jonathan Safran Foer in “Eating Animals,” “of living in the moment when the critique of factory farming broke into public consciousness.” That opportunity critically depends on understanding where cruelty is present, and where it’s absent.

I have argued that eating less meat — adopting a reducetarian, vegetarian, or vegan diet according to our individual abilities — is an ethical way to put our large, evolved brains to good use for the sake of our planet (reducing global warming), other animals (reducing animal suffering), and our bodies (reducing meat-induced physical harms). A balky response often comes back to me: “But many animals eat other animals! It’s the natural way of the world!”

It’s precisely cruelty that makes what Gregory Bateson called “the difference which makes a difference.” We know — or we can know, if we choose — that we are in relationship with the other animals on our planet. We know — or we can know, if we choose — that we can eliminate or reduce the cruelty we inflict on other animals’ bodies. The bears I write of are not, of course, “bile bears” any more than chickens and pigs are “factory farm animals.” They don’t exist for the use we can make of them. They are inherently valuable animals with their own thoughts and emotions who want to live untethered.

Barbara J. King, emerita professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary, is also the author of “How Animals Grieve” and “Evolving God.”

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I’ve just read an article here in which one reads in the title that Chinese culture, among all other, is the one that feel emotions more physically. I tend to think that is true. Physically only! Not emotionally. Based on the cruelty they have been inflicting to animals nowadays (dogs and cats at the ‘horror festival, let alone these bear-bile farms) — they seem to me the heartless and soulless people in the world. Period. Of course, South Koreans with that other horror called Bok Nal ‘festival’ are very close to Chineses when the subject is cruelty to animals. I do not understand Asian culture at all. Unfortunately, they seem to me soulless people.

“endegenous wind” or inner wind was a chinese language phrase that can translate stroke or other seisure disorders. Term more descriptive than causal. Exterior wind would be a common “cold.” In-flu-enza comes from confluence of river of stars.

That is a brilliant article. I think that the bike farms are as you mentioned cruel. I also believe that the farmers that cause pain and cruelty to animals in poorer countries do so because that is all they know and their father did it. We need to ( the governments) reeducate so they are able to put food on the table.

I absolutely adore animals they are nicer to be with and nicer to each other and yes they do hurt, which is the balance of life.

It’s the cruelty westerners are probably the worst offenders as they know the hurt they are inflicting and they don’t appear to have empathy for life animal or human and that is extremely sad and scary for our children.

Thank you for this thoughtful and profoundly moving essay. This comes home to me as one of the stranger transformative experiences that the mind is capable of entering when ripe, and prompted. The birth of my son was my own gateway into feeling the animal continuum running through me, a vivid instinctual life with unignorable moral implications. Very pleased that the “Gregory Bateson” Google alert I have set up has brought me this essay.

This is a horrendous abuse of power over innocent animals and must be stopped.