Testing the Waters

Drink more water, the health gurus say. And so we do.

Americans downed 12.7 billion gallons of bottled water in 2016 and paid $15.8 billion for the privilege. For the first time last year, bottled water surpassed soft drinks as the top-selling beverage in the United States. And bottled water comes increasingly from municipal water supplies, which have their own vast network of customers. We’re drinking to our health, eight glasses a day.

But what’s in the water, and how do we know if it’s really healthy to drink?

A few months ago, organizers invited me to be a judge at the 27th annual Berkeley Springs International Water Tasting. The event, in the small West Virginia town where George Washington famously “took the waters” to heal his wounds, bills itself as the world’s largest and longest-running water-tasting competition.

Like many environmental reporters, I’d been following the story of Flint, Michigan. A combination of economic shortcuts and bureaucratic malfeasance led to a crisis where residents were poisoned by their own government. It is, and continues to be, a tragedy. But the broader story is the slow drip.

Des Moines’ municipal water works sued upstream rural counties because, for decades, farmers’ fertilizer has been adding too many nitrates to the water supply. A judge dismissed the case earlier this spring, kicking it back to the state to resolve. In Pennsylvania, the Octoraro treatment plant built a reservoir to guarantee a clean supply of water, only to be forced to blend it with Susquehanna River water — or not use it at all — because of the nitrates coming from the farm-field fertilizers used by the Amish. Many West Virginia communities face increasing bromide levels in their water because of hydraulic fracturing and other extraction industries. While bromide is not harmful on its own in low doses, when mixed with the chlorine often used to treat water, it can lead to the formation of the suspected carcinogens trihalomethanes. Even Berkeley Springs, a town known for its water purity, is not immune. Just three miles from its public baths, U.S. Silica is blasting through sand-colored hills to mine minerals for making glass. The company has notified residents that it will be mining even closer to their homes.

Would I be able to taste whether something was amiss in my own Baltimore tap water? And how would I judge a product whose most famous attribute is its lack of taste?

Fortunately, I had an accomplished teacher. Arthur von Wiesenberger comes to Berkeley Springs each year to train the judges and serve as master of ceremonies. Von Wiesenberger grew up in New York and Italy and now lives in Santa Barbara, where he says the tap water is so bad “you could chew it.” He has been drinking bottled water all his life. Americans, he said, prefer a tasteless product, while Europeans like one where the minerals stand out.

Sodium makes water salty. Calcium hardens it. Silica makes it feel slippery. Magnesium in water is a high priority for the French, who find it reduces the kidney-stone problems often produced by their rich diets, von Wiesenberger said. Magnesium-infused water was once popular in the United States, where a company in French Lick, Indiana, billed a product called Pluto Water as “America’s laxative” with the tagline, “When nature won’t, Pluto will.” Sales halted in 1971, when the U.S. listed lithium, one of Pluto Water’s ingredients, as a controlled substance.

Different countries may be used to different tastes, but no country likes a smell in the water, nor anything floating in it. A good way to start determining a water’s safety, von Wiesenberger says, is to look and sniff. A yellow tinge indicates sulfur, as does a rotten-egg smell. Greenish hues mean algae. Orange is a sign of high iron, and so is the rusty-nail smell that accompanies it. Once von Wiesenberger inhaled a strong pumpkin odor. It turned out to be a weed killer.

“None of that is desirable,” he says.

So what were we looking for, in tasting the tasteless and smelling the odorless? On that, von Wiesenberger was clear: “Pure. Clean. Fresh. Refreshing.” We would do four tastings of about 20 waters each — tap, purified, bottled, and carbonated. After 20 waters, von Wiesenberger told us, we’d have palette fatigue. Also, we might need to pee.

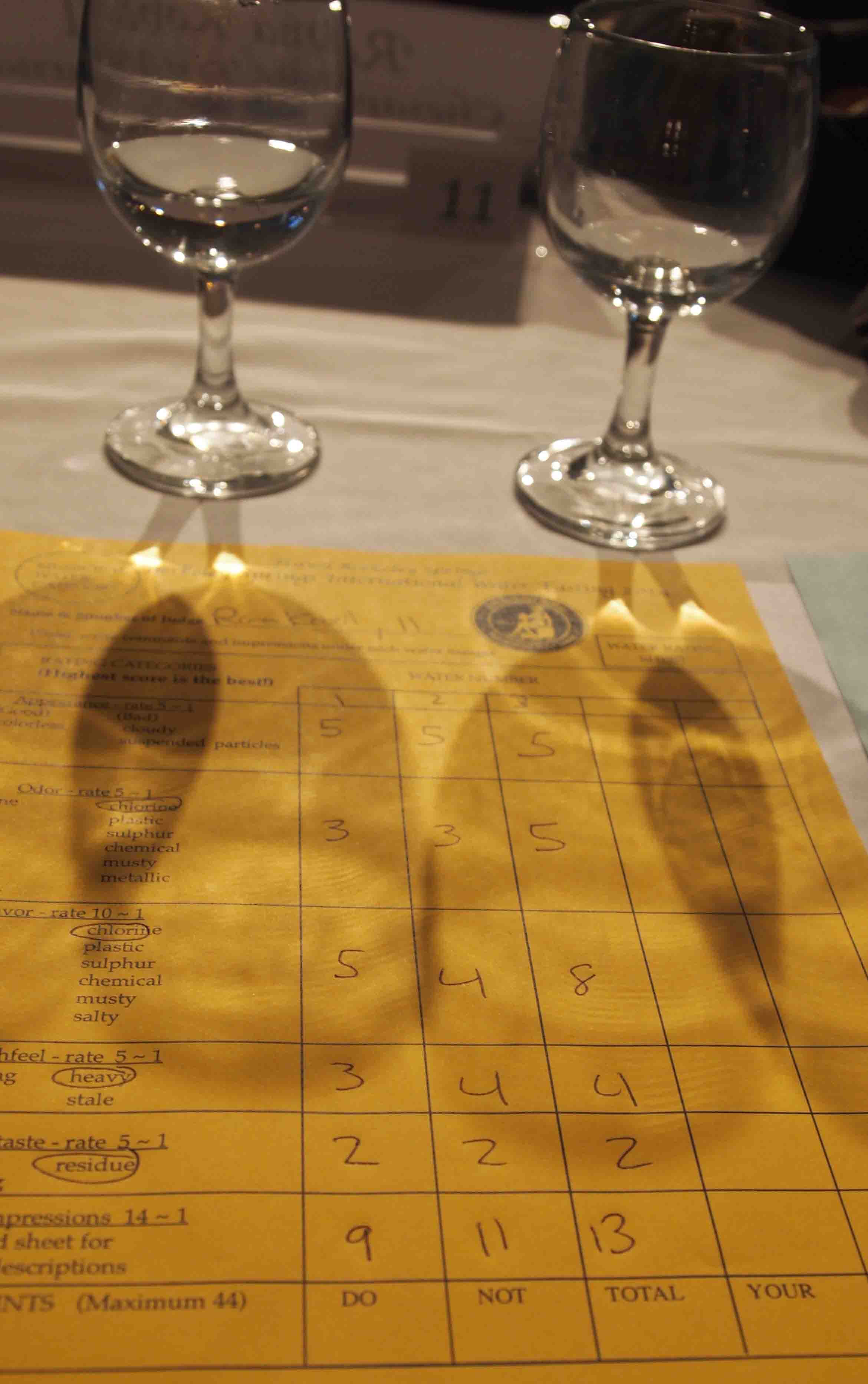

Our panel of 11 judges included regional food writers, bloggers, radio and TV producers, and me. We were to sip the water from wine glasses. The hosts provided water crackers if we needed a break. We were to rate the water on a scale of one (bad) to five (great) for its appearance, odor, mouthfeel, and aftertaste. Von Wiesenberger patiently informed us that there were no right or wrong answers. Still, I found myself looking at the paper of the judge next to me, a West Virginia writer who calls himself “the Food Guy.” We seemed to like and dislike the same waters, but my grades were far more generous.

In the end, Montpelier, Ohio, won best tap water. Products from Ocala, Florida and from Crete tied for best bottled. A Bosnian brand took best carbonated, while Toronto’s GP8 Oxygen Water took best purified. Berkeley Springs’ own purified water finished second.

When the contest ended, von Wiesenberger and co-host Jill Klein Rone opened the wooden dance floor to “the stampede,” when dozens of locals and out-of-towners rush to fill shopping bags with bottled water samples.

I see the appeal, but the best water in Berkeley Springs wasn’t in the judge’s room. It was outside, in Berkeley Springs State Park, where a spigot flows and visitors are invited to take natural spring water for a small donation. (I also recommend a foot soak, which is free.)

I went home to Baltimore, mindful of how to spot trouble but committed to continuing to drink water from my tap. The health gurus keep saying it’s good for you. But then again, a recent headline in the Livestrong health newsletter says “Drinking Your Own Pee Is the Latest Health Craze.” I’ll stick to H2O.

Rona Kobell is a staff writer for the Chesapeake Bay Journal. She can be reached at [email protected]

This piece has been updated from an earlier version.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Caution! Berkley Springs water made me sick for weeks!

BOIL IT FIRST!