Unsung: James Ellis LuValle

With all the excitement surrounding the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, it seems appropriate, in our ongoing mission to highlight unsung African American scientists, to cast back a few decades to the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, Germany. Aside from the games’ unfolding under the auspices of an ascendant Nazi regime, the 11th Olympiad is perhaps best known for the singular performance of Jesse Owens, who undercut Adolf Hitler’s notions of Aryan superiority over other races – including African Americans – by taking home four gold medals. (I highly recommend watching the movie “Race,” which was released last year and provided a thought-provoking narrative about the achievements of Owens.)

Less familiar to many readers, however, might be another African-American competitor at the 1936 Olympic Games: James Ellis LuValle, who earned a bronze medal in the 400-meter event. Four years later, he would earn a PhD in physical chemistry (with a minor in mathematics) from the California Institute of Technology under the guidance of chemistry pioneer Linus Pauling.

LuValle was born in San Antonio in November of 1912. His father, James A. LuValle, was a minister, and his mother, Isabel Ellis, was a music teacher. James had a younger sister named Mayme E. LuValle. The family briefly lived in Washington, D.C. and later settled in southern California.

After graduating from Los Angeles Polytechnic High School, LuValle begin his college studies at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and earned his B.A. in chemistry in 1936 — the same year he competed in the Olympic Games in Berlin. During a 1988 interview, LuValle fondly recalled the excitement surrounding Jesse Owens when the Olympic team arrived in Berlin. According to LuValle, there was a crowd of excited teenage girls yelling, “Wo ist Jesse?” (Where is Jesse?), and Owens needed to have security with him in Berlin.

Nearing the completion of his undergraduate degree in chemistry, UCLA had established a master’s degree program. When he returned from the Olympics, LuValle received a telegram from his mother indicating he received a graduate assistantship from UCLA. LuValle earned his MA degree in 1937 from UCLA, where he focused on photochemistry, where light is used to initiate and study chemical reactions. LuValle co-authored a peer-reviewed article on these results in the prestigious Journal of the American Chemical Society.

LuValle then decided to further his studies and pursue a doctoral degree in chemistry.

“I applied to several schools — Harvard and Wisconsin — to go for a PhD and didn’t get anything from Wisconsin,” he recalled during that 1988 exchange with interviewer George Hodak, “but got a half of a scholarship from Harvard.” LuValle’s UCLA professors in physics and mathematics intervened on his behalf by talking with Professor Linus Pauling at Caltech, and subsequently he received a graduate assistantship to attend Caltech.

LuValle worked for Pauling during his last two years of graduate study at Caltech and received fellowship support from the Julius Rosenwald Fund, which provided funding support to African Americans and white Southerners. The Director of Fellowships, George M. Reynolds requested a letter of support from Pauling for the renewal request on behalf of LuValle.

Pauling responded to Reynolds on December 20, 1938: “I am very glad indeed to give a strong letter of recommendation to you for the renewal of the Rosenwald Fund Grant to Mr. James E. LuValle. Mr. LuValle has made an excellent record of his graduate work with us. There is very little doubt that he will have completed by June 1940 a thoroughly satisfactory doctor’s dissertation and will receive his doctorate at the time, if he is able to continue his studies. He is hoping then to be given an appointment in some university, such as Fisk, and I believe that with his many qualifications he will surely receive an appointment of this type.”

After earning his PhD, LuValle accepted an appointment as an instructor at Fisk University, one of the nation’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU), in Nashville, Tennessee. (Another Undark “Unsung” hero, Dr. Evelyn Boyd Granville, also taught at Fisk University.)

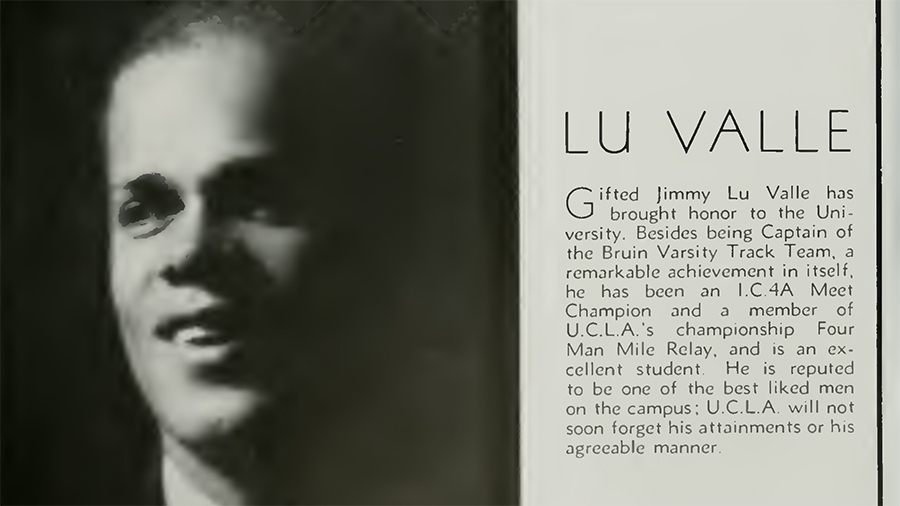

A year before his Olympic debut, LuValle’s UCLA classmates described him as “one of the best liked men on campus.”

Visual: UCLA

In 1941, LuValle left academia for an appointment as a Senior Research Chemist at Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York. LuValle was thrilled about his new appointment and in September, 1941, he wrote a letter to Pauling about his new position.

“Kodak is certainly a good firm in which to be employed,” LuValle wrote. “They do so much for their employees. The men and women in the research labs have all been very nice and very helpful to me. I like the work I am doing. It is interesting and fun, and I like the people with whom I work.”

LuValle was the first African American to work for Kodak research labs, and he remained with the company until 1953, holding various appointments where his research efforts focused on multiple projects including photographic developing agents and investigating the stability of dyes.

During his career, LuValle held positions at various industrial companies including Technical Operations, Inc. in Burlington, Massachusetts, where he served as a Senior Scientist and the Head of the Photographic Chemistry Department from 1953 until 1959, and Fairchild Space and Defense Systems in Syosset, New York, where he was Director of Research until 1968. LuValle returned to California and served as Scientific Coordinator for Palo Alto Research and Engineering from 1971 to 1975. He also served as Director of Undergraduate Chemistry labs at Stanford University.

During the course of his career, LuValle’s intellectual contributions included publishing over 30 peer-reviewed scientific journal articles, and he held eight patents. In 1987, LuValle received the Alumni Distinguished Service Award from California Institute of Technology and the Professional Achievement Award from the UCLA, where the student commons was named in his honor in 1985.

LuValle married his wife, Jean — also a chemist — in 1946. The couple had three children who all pursued careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The couple’s eldest son, John Vernon, earned a degree in physics at Williams College, and the younger son, Michael James earned a PhD in statistics from the University of California, Davis. The couple’s daughter, Phyllis Ann, earned a doctoral degree in molecular biology from the University of Utah.

LuValle recalled his children fondly to Hodak in 1988. “Now, this is a young lady who, when she was a teenager, if you mentioned the word science would say, ‘Ugh,’” said LuValle, who died in 1993. “So, I’m very proud of all of them, and very proud of that daughter of mine.”

Asked in that same interview about his history of combining sports and study, LuValle made clear his priorities. “To run in the spring, I had to take a heavy course load in the fall,” he said. “I usually also figured on taking courses in the summer. So I would go light in the spring so I could be away and compete.

“Remember,” LuValle added, “at this time, athletics was purely a sideline. The main thing was I was trying to get an education in the sciences. I had a combined major in chemistry, physics and math. It kept me busy.”

Sibrina Collins is an organometallic chemist and former writer and editor for the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C. In July, 2016, she became the first executive director of the Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, Michigan.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Thank you

I always enjoy finding new writings about him

Dear Michael, Your father was such a good friend to me and an inspiration while I completed my PhD in physical chemistry at Stanford. I still have a coffee mug that he gave me.

i really like this article because it inspires me to do better things and wants myself to be a better person and a better worker

this was an awesome article and James E. LuValle was a well educated man and a athletic person R.I.P James LuValle

Thank you for your kind words. Much appreciated.

Sibrina

Mr. Howard Romaine,

Thank you so much!

I enjoyed this piece a lot and remember 4-5

labs a week, taking organic, quantitative and

biochemistry, spring 63,then running windsprints under Freeman Marr, coach at Southwestern at Memphis, to get ready for mile

half mile, and 2 mile meets on weekend..only pay we got was a steak a week at some little Greek place down the street!!!