While covering technology for The New York Times in the early 2000s, I became obsessed with what I considered an enormous question: As online resources become the main tool for gathering information, are those items left behind, in non-digital form, in danger of disappearing from the collective cultural memory, potentially leaving our historical fabric riddled with holes?

It was a question I couldn’t seem to shake. “This is profound,” I told anyone willing to listen. “It redefines the boundaries of knowledge.”

BOOK REVIEW — “The Map of Knowledge: A Thousand-Year History of How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found,” by Violet Moller (Doubleday, 336 pages).

My editors at The Times were bemused by my badgering them to cover this as if it were breaking news. Still, they ran a story or two on the topic.

Imagine my delight at discovering Violet Moller’s unusual new book, “The Map of Knowledge: A Thousand-Year History of How Classical Ideas Were Lost and Found,” which follows a small band of ancient scientific texts on their journey through the Middle Ages.

It was while studying classics and history, writes Moller, a British historian, that “I began to wonder what had happened to the books on mathematics, astronomy, and medicine from the ancient world. How did they survive? Who recopied and translated them? Where were the safe havens that ensured their preservation?”

The foundations of modern knowledge were laid by the ancient Greeks, their ideas written on scrolls and stored in libraries throughout the Mediterranean and beyond. But as the sprawling Roman Empire began to disintegrate, these precious texts grew imperiled. Books were burned and the great Library of Alexandria, the universal collector of all knowledge, gradually disappeared.

Moller looks at the years spanning roughly 500 to 1500 A.D., a period when classical Greece and Rome sent out a diaspora of ideas, ones that found their way to Islamic societies in the Middle East and Spain, and eventually returned to Renaissance Europe.

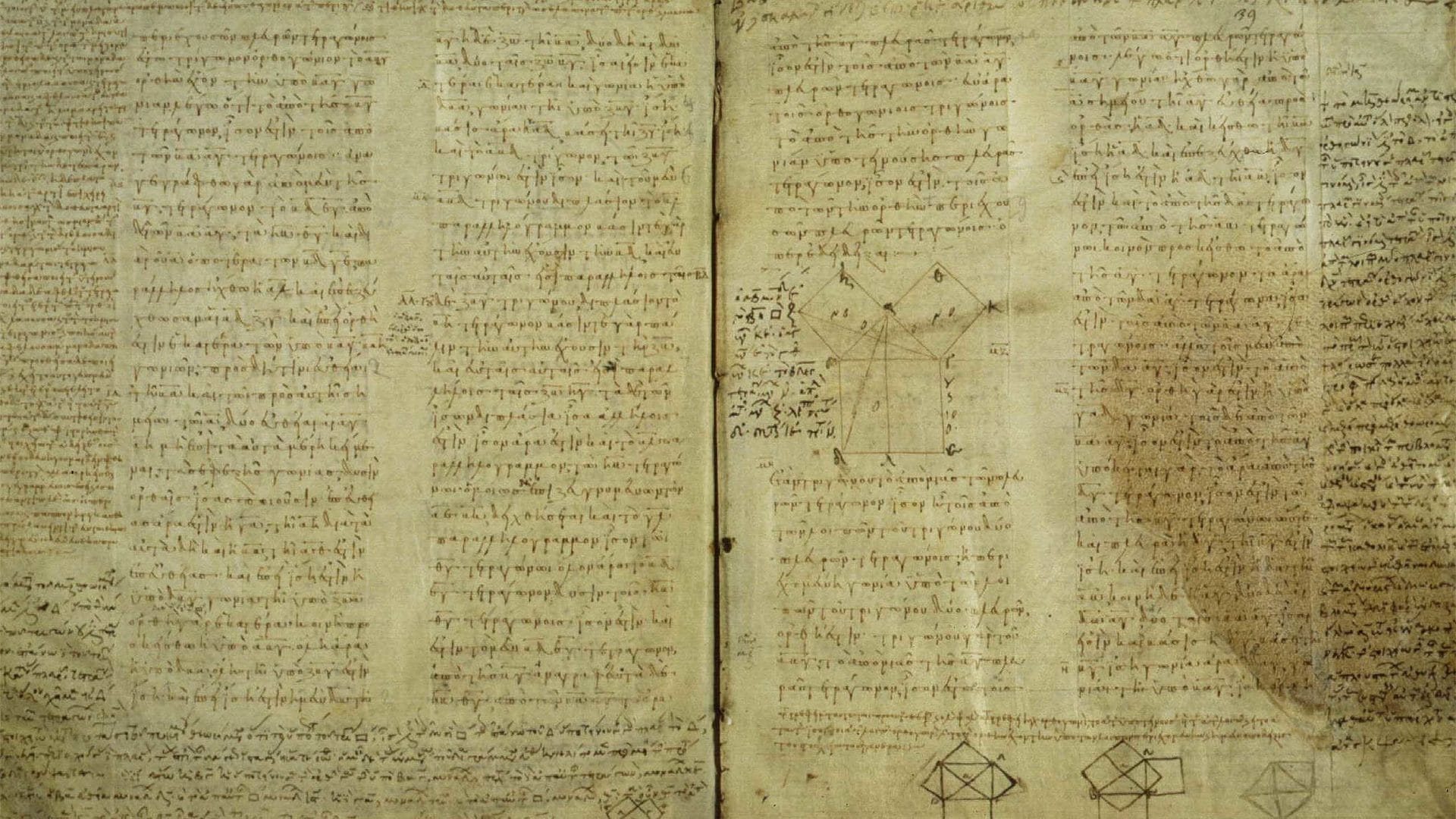

She chronicles the journey of works by Euclid, the father of geometry; physician and surgeon Galen of Pergamon; and astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, as they were “filtered through the minds of scribes and translators, transformed and extended by brilliant scholars in the Arab world.” The survival and preservation of these texts was due to a series of fortunate twists of fate.

Moller devotes seven chapters to seven cities: Alexandria, Baghdad, Córdoba, Toledo, Salerno, Palermo and, finally, Venice.

It was in Alexandria that Euclid wrote his “Elements,” around 300 B.C. Ptolemy wrote his geocentric treatise on the universe, the “Syntaxis Mathematica,” which became known as the Almagest, in second-century Alexandria. Galen spent time in Alexandria but wrote his major works on medicine — the basis for medical studies for centuries — around 160 A.D. in Pergamon.

As conceits go, Moller’s is an admirable one. She starts the journey in the sixth century, as the dark ages were descending, with Alexandria on the wane, and “the fate of these three great strands of ancient science uncertain.”

Enter Baghdad, a city that serves as Moller’s most compelling backdrop, as she describes the influence of medieval Arab intellectuals on Western ideas. In the late eighth century, Moller writes, “a new product arrived in Baghdad that would transform the world of books forever: paper.”

The same period brought advances in the manufacture of ink and glue, as well as bookbinding techniques. In the late eighth century, Yahya ibn Khalid, scion of a powerful Persian family, commissioned the first translation of “Elements.” Members of the Baghdad elite followed his example, pouring money into the recovery of ancient texts.

While religion dictated the cultural winds of the Western world, ideas flowed freely through the Middle East, traversing religions and cultures. Knowledge began flowing into Baghdad from every direction as scholars translated Greek manuscripts into Arabic. Book production soared as texts were read aloud to roomfuls of scribes so that many copies could be made at once. Ptolemy’s Earth-centric explanation of the universe was translated into Arabic early in the ninth century.

Yet Arab scholars, Moller points out, were gradually written out of history.

Moller leaves Baghdad and heads to Córdoba, which by the 10th century had become a hub of scholarship. This was thanks in large part to Crown Prince al-Hakam, who supported the sciences, built a vast network of scholarly contacts, and combined Córdoba’s three royal libraries into one, which contained 400,000 volumes. Copies of Euclid’s “Elements,” Ptolemy’s “Almagest,” and the Galenic corpus came to Córdoba from points East; they were copied in turn and made their way into the hands of scholars.

Luckily, some of those copies reached Toledo. It was there that an impassioned young scholar named Gerard translated “The Almagest” into Latin, the first such translation disseminated throughout Europe.

This was a lucky turn of events, Moller points out, as 700 years of Muslim civilization – including nearly all writings in Arabic – were snuffed out under Catholic rule.

Next stop: Salerno, which in the 11th century became a hub of learning, followed by an exploration of 12th century Palermo which had become a haven for intellectual scholarship. Finally to Venice, where the poet and scholar Petrarch arrived in 1351 to learn Greek so he could translate ancient texts. Venice became a center of book publishing, the gold standard for the preservation of ideas, thus safeguarding the intellectual legacies of Euclid, Ptolemy, and Galen.

“The Map of Knowledge” glosses over many a major epochal turn. Then again, a 270-page book (not counting notes and bibliography) that spans a thousand-year period can be excused for dispatching entire swaths of history in a dependent clause. And there are passages — some several pages in length — where Moller’s writing turns dry, reading more like a police report than a history aimed at a popular audience.

Still, we can thank Moller, not only for having posed her initial question — how did these critical texts manage to survive when so much else did not — but also for having the gumption to pursue the answer.

Katie Hafner is a journalist who writes about health care. She is the author of six works of nonfiction, most recently a memoir, “Mother Daughter Me” (Random House), and is at work on a novel. She can be reached on Twitter at @KatieHafner.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Hopefully this original data will survive the pending “dark age” of pseudo science!

See hinges of history series by thomas cahill