In Sudan, Rediscovering Ancient Nubia Before It’s Too Late

In 1905, British archaeologists descended on a sliver of eastern Africa, aiming to uncover and extract artifacts from 3,000-year-old temples. They left mostly with photographs, discouraged by the ever-shifting sand dunes that blanketed the land. “We sank up to the knees at every step,” Wallis Budge, the British Egyptologist and philologist, wrote at the time, adding: “[We] made several trial diggings in other parts of the site, but we found nothing worth carrying away.”

For the next century, the region known as Nubia — home to civilizations older than the dynastic Egyptians, skirting the Nile River in what is today northern Sudan and southern Egypt — was paid relatively little attention. The land was inhospitable, and some archaeologists of the era subtly or explicitly dismissed the notion that black Africans were capable of creating art, technology, and metropolises like those from Egypt or Rome. Modern textbooks still treat ancient Nubia like a mere annex to Egypt: a few paragraphs on black pharaohs, at most.

Today, archaeologists are realizing how wrong their predecessors were — and how little time they have left to uncover and fully understand Nubia’s historical significance.

“This is one of the great, earliest-known civilizations in the world,” says Neal Spencer, an archaeologist with the British Museum. For the past ten years, Spencer has traveled to a site his academic predecessors photographed a century ago, called Amara West, around 100 miles south of the Egyptian border in Sudan. Armed with a device called a magnetometer, which measures the patterns of magnetism in the features hidden underground, Spencer plots thousands of readings to reveal entire neighborhoods beneath the sand, the bases of pyramids, and round burial mounds, called tumuli, over tombs where skeletons rest on funerary beds – unique to Nubia — dating from 1,300 to 800 B.C.

Sites like this can be found up and down the Nile River in northern Sudan, and at each one, archaeologists are uncovering hundreds of artifacts, decorated tombs, temples, and towns. Each finding is precious, the scientists say, because they provide clues about who the ancient Nubians were, what art they made, what language they spoke, how they worshipped, and how they died — valuable puzzle pieces in the quest to understand the mosaic of human civilization writ large. And yet, everything from hydroelectric dams to desertification in northern Sudan threaten to overtake, and in some cases, erase these hallowed archaeological grounds. Now, scientists armed with an array of technologies — and a quickened sense of purpose — are scrambling to uncover and document what they can before the window of discovery closes on what remains of ancient Nubia.

“Only now do we realize how much pristine archaeology is just waiting to be found,” says David Edwards, an archaeologist at the University of Leicester in the U.K.

“But just as we are becoming aware it’s there, it’s gone,” he adds. Within the next 10 years, Edwards says, “most of ancient Nubia might be swept away.”

Between 5,000 and 3,000 B.C., humans across Africa were migrating to the Nile’s lush banks as the Earth warmed and equatorial jungles transformed into the deserts they are today. “You cannot go 50 kilometers along the Nile River Valley without finding an important site because humans spent thousands of years here in the same place, from prehistoric to modern times,” Vincent Francigny, the director of the French Archeological Unit, tells me in his office in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum. Nearby his office, the White Nile from Uganda and the Blue Nile from Ethiopia unite into one river that flows through Nubia, enters Egypt and exits into the Mediterranean Sea.

Roughly around 2,000 B.C., archaeologists find the first traces of the Nubian kingdom called Kush. Egyptians conquered parts of the Kushite Kingdom for a few hundred years, and around 1,000 B.C., Egyptians appear to have died, left, or mixed thoroughly with the local population. At 800 B.C., Kushite kings, also known as the black pharaohs, took over Egypt for a century — two cobras decorating the pharaohs’ crowns signify the unification of kingdoms. And somewhere around 300 A.D., the Kushite empire began to fade away.

In the early 20th century, Harvard archaeologist George Reisner discovered dozens of pyramids and temples in Sudan. But with unquestioning condescension, he — like many of his contemporaries — attributed any sophisticated architecture to a light-skinned race. (Image via Wikimedia)

Almost nothing is known about what life was like for people living in Nubia during this time. British Egyptologists of the 19th century often relied on accounts from ancient Greek historians who fabricated wild tales, Francigny says, never bothering to go to Sudan themselves. Some details were filled in by Harvard archaeologist George Reisner in the first part of the 20th century. Reisner discovered dozens of pyramids and temples in Sudan, recorded the names of kings, and shipped the most precious antiquities to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. With no evidence and unquestioning condescension, he attributed any sophisticated architecture to a light-skinned race. In a 1918 bulletin for the museum, he matter-of-factly wrote, “The native negroid race had never developed either its trade or any industry worthy of mention, and owed their cultural position to the Egyptian immigrants and to the imported Egyptian civilization.” And believing that skin pigmentation marked intellectual inferiority, he attributed the downfall of ancient Nubia to racial intermarriage.

Besides belonging to an overtly racist period, Reisner was a member of an old wave of archaeology that was more interested in recording the names of royalty and retrieving treasures than looking at antiquities as a means to understand the evolution of societies and cultures. Stuart Tyson Smith, an archaeologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, takes a newer approach when he brushes dust from objects he’s found in Nubian tombs over the past several years. Underground burial chambers hold skeletons whose bones are probed for details about age, health, and place of origin, as well as cultural clues, since the dead were buried with belongings. Smith and his team have been excavating a huge necropolis south of Spencer’s locale, called Tombos, that was in use for hundreds of years before the seventh century B.C.

Smith gleefully invites me into storerooms in Tombos overflowing with items he and his team have recently found. Our ancestors considered vanity on the journey to the land of the dead: They were buried beside kohl eyeliner, vases of cologne, and intricately painted cosmetics boxes. Smith cradles a clay incense burner shaped like a duck. He’s found one other like it, from a period around 1,100 B.C. “They had fads, like us,” Smith says, “Like, you just gotta get one of those duck incense things for the funeral.”

A woman’s skull half coated with termite-riddled dirt rests on a wooden table. Smith beams and locates an amulet the size of his fist that he found beside this skeleton. The amulet is shaped like a scarab beetle, a common symbol of rebirth in Egypt, but the insect bears a man’s head. “This is very unusual,” Smith says. He laughs as he paraphrases hieroglyphics etched into the scarab’s underside: “On the day of judgment, let my heart not testify against me.”

Smith’s colleague, Michele Buzon, a bioarchaeologist at Purdue University, will ship the skull back to her lab in Indiana to analyze the isotopic composition of strontium buried in tooth enamel. Strontium is an element found in rocks and soil, which varies from place to place. Because strontium integrates into layers of enamel as children grow, it signals where a person was born. It will reveal whether this woman was from Egypt, as the scarab suggests, or a local with a taste for Egyptian-like things.

So far, it seems clear that Egyptian officials lived and died alongside Nubians in Tombos between 1,450 to 1,100 B.C. Egypt taxed the region, which was a hub for trade, with ivory, gold, and animal pelts transported up the Nile from the south. But by 900 B.C., Buzon rarely finds indications of Egyptian roots buried in tooth enamel. Strontium isotopes reveal that people were born and raised in Nubia, although an Egyptian influence remained embedded in the culture. In many ways, it is an early sign of artistic appropriation. “They were creating new forms,” Smith says.

In 2005, he excavated a burial chamber with a male skeleton, filled with Nubian arrowheads, objects imported from the Middle East, and a copper cup with charging bulls engraved within — the cattle being commonplace in Nubian designs. “Although he’s got these traditional Nubian objects, there is also this cosmopolitan stuff that shows he’s part of the in-crowd,” Smith explains.

“This period has been burdened by racist colonial interpretations assuming that Nubians were backwater and inferior and now we can tell the story of this remarkable civilization,” he adds.

With so little known about life in ancient Nubia, every object that’s uncovered could prove to be invaluable. “We are rewriting history here,” Smith says, “not just finding one more mummy.”

That said, a member of Smith’s group did discover naturally mummified remains at an ancient cemetery near Tombos, called Abu Fatima. Sarah Schrader, a bioarchaeologist now based at Leiden University in the Netherlands, was on her knees in a dirt pit, chipping at mud cemented onto the skin of a disembodied human leg when she brushed away loose sand and saw a lump. “Oh my God, an ear!” she yelled. “Orocumbu!” she called out, using the Nubian word for head — an alert for a few local staff nearby. Trading the trawl for a brush, she exposed a mat of curly black hair. And when she swept away sand lower down, her stomach turned. A plump tongue stuck out below two front teeth. After taking a quick break, Schrader excavated the rest of the head.

Schrader packaged the head carefully, and plans to ship it to a humidity-controlled chamber in the Netherlands. There, she will date the bones and assess strontium from the man’s tooth enamel to learn where he was from. Finally, his fleshiness gives her hope that ancient DNA might be extracted. With genetic sequencing, researchers might determine if modern-day Nubians, Egyptians, or one of hundreds of ethnic groups from the surrounding regions might trace their heritage to this early civilization.

To find the lost language of ancient Nubia, I sought out Claude Rilly, a linguist specializing in ancient languages, at Soleb and Sedeinga — sites recognized by majestic and crumbling temples and a field of small pyramids. The stretch of desert between those sites and Tombos is post-apocalyptic: scorched, flat earth and sable boulders as far as the eye can see. At a point when sand completely covers the road, I transfer into a rickety motorboat. Rilly is waiting on the riverbank. A towering man with a weathered face and easy grin, he welcomes me by saying, “Here we are in the cradle of humanity — in the place where human beings have the oldest home.”

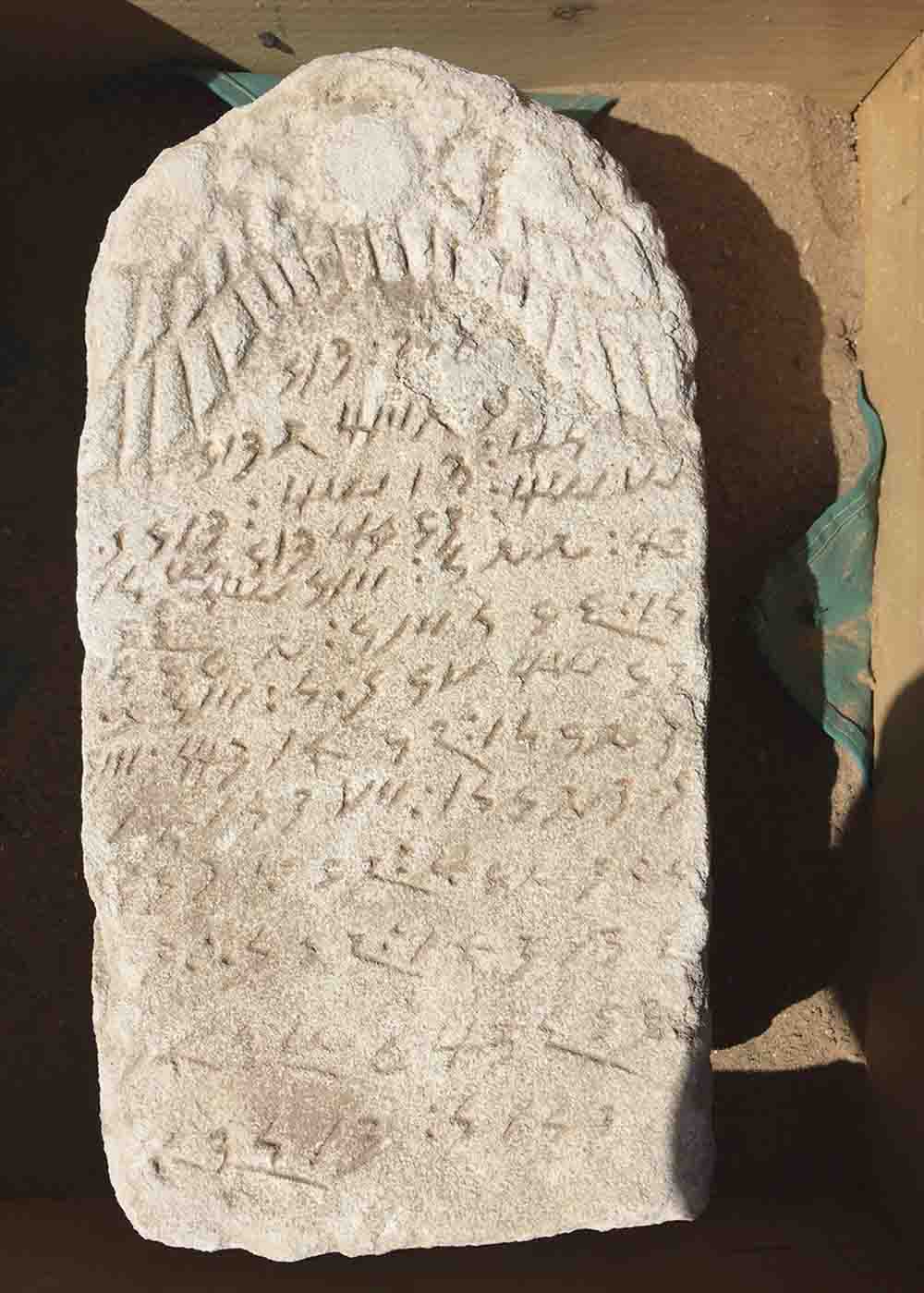

Unprompted, Rilly begins to translate Egyptian hieroglyphics etched into the sandstone columns of the temple at Soleb. But he is eager to show off his most valuable finds: stele, stone slabs engraved with Meroitic text from ancient Nubia. Based at the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris, Rilly is one of only a few people who can translate Meroitic text. It’s unrelated to Egyptian hieroglyphics. Rather, Rilly has found ties between Meroitic and a handful of languages spoken today by ethnic groups in Nubia, Darfur, and Eritrea.

To figure out what the words mean, he compares each precious tablet of text to another, searching for commonalities and themes. He lifts a recently discovered stele out of a wooden Dewar’s whiskey box, and squints at the letters. They fall into slants like heavy metal logos. He explains that the inscription begins with an appeal to the gods, and ends with a benediction: “May you have plentiful water, plentiful bread, and may you eat a good meal.” But there is a word in the middle of the gravestone that Rilly does not know. “It is guess work,” he says, “I’m not sure if this adjective means supreme or something else.”

In late 2016, Rilly found a painted stele that had fallen between the bricks of a funerary chapel at Sedeinga and was shielded from sand storms and rain. The top of the stone is decorated with a sun disk encircled by a pair of golden yellow cobras, and surrounded by a pair of red wings. An engraved line separating the illustration from the text is blue — a rare pigment. And the text includes a word Rilly has never before seen. Based on languages spoken in the region today, he suspects it’s a second term for the sun — one for the god of the sun as opposed to the physical sun, the star.

Rilly is desperate to find more text so that he can narrow down the meanings of more words, and decode the stories they tell about Nubian religion. He feels there must be a buried city near the temples, where our ancestors might have left notes on papyrus. This month, Rilly’s team will drag a magnetometer around the region to search for signs of a settlement buried beneath farms along the Nile or the surrounding encrusted land. The boxy machine calculates the magnetic signal at the surface of the ground, and compares it to the signal two meters below. If the density between the spots is different, the point is assigned a medium-gray to black shade on a map of the region, indicating that something irregular lies underground.

Rilly also seeks the remains of a Kushite temple referred to in the stele he’s decoded thus far. “There are at least 15 mentions of Isis, as well as the god of the sun and the god of the moon,” Rilly says. “We know there was a Kushite cult here, and a cult cannot exist without a temple.”

Modern-day Nubians have heard tales about ancient Nubia, passed down through the generations. And whether or not they descend directly from the Kushites, the past is inextricably intertwined with their identity. They’ve grown up amid fallen statues, temples, and pyramids. On holy days, families from the Nile River town of Karima hike up the sandy side of Jebel Barkal, a holy mountain that is distinguished by a 250-foot spired pinnacle that was decorated with etchings perhaps 3,400 years ago. As the sun sets, the view can only be described as biblical, stretching from the green banks of the Nile to a dozen temples in the shadow of the mountain, to pyramids on the horizon.

When ancient Egyptians conquered the region, they identified Jebel Barkal as the residence of the god Amun, who was believed to help renew life each year when the Nile flooded. They carved a temple into its base, and illustrated the walls with gods and goddesses. And when ancient Nubians regained control, they converted the holy mountain into a place for royal coronations, and constructed pyramids for royalty beside it.

There is another holy mountain further north on the Nile, in a town where Ali Osman Mohamed Salih, a 72-year old professor of archaeology and Nubian studies at the University of Khartoum, was born. His parents taught him that God lives in the mountain, and that because people come from God, they too are made of the mountain. This logic links the present with the past, and a people with a place. Salih says it means, “You are as old as the mountain, and nobody can get you out of this land.”

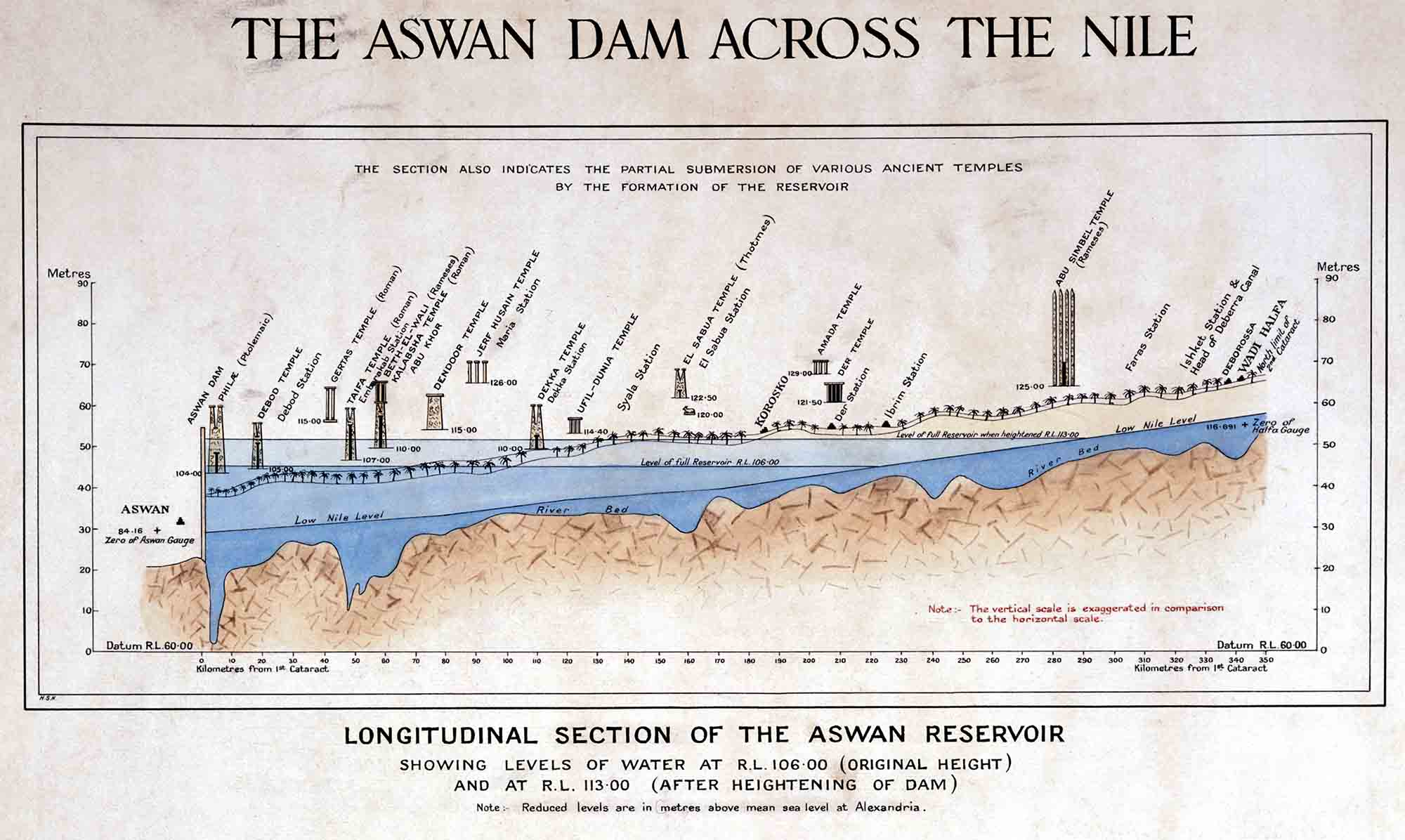

Salih is concerned that three new hydroelectric dams that Sudan’s government has planned along the Nile might do just that — along with drown Nubian artifacts. According to an assessment by Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, the reservoir created by one planned dam near the town of Kajbar would flood more than 500 archeological sites, including more than 1,600 rock etchings and drawings dating from the Neolithic period through medieval times. Estimates from activists in Sudan suggest that hundreds of thousands of people could be displaced by the dams.

Salih has protested Nile River dams before. While passing through Egypt on his way back home in 1967, he was detained in Cairo for his open opposition to the Aswan High Dam near the border of Sudan in Egypt. The dam created a 300-mile long reservoir that submerged hundreds of archeological sites, although the most grandiose were relocated to museums. It also forced more than 100,000 people — many of them Nubians — from their homes. Governments of countries along the Nile justify hydroelectric dams by pointing to a need for electricity. Today, two-thirds of Sudan’s population lacks it. However, history shows that those whose lives are uprooted are not always those who benefit from electricity and the profit it generates.

But there’s little room for negotiation. Sudan’s president, Omar al-Bashir, a war criminal according to the International Criminal Court, rules the country with an iron fist. Since 2006, his security forces have shot more than 170 people and beaten, imprisoned, and tortured many others who have protested the dams and other politically charged topics. International archaeologists who wish to continue working in the country dare not speak ill of the dams on record. And most national archaeologists stay mum knowing they could disappear into jails.

Other wonders, such as Jebel Barkal and Tombos, are threatened more acutely by population growth and the desire to live modern lives with higher education and electricity. The mummified head at Abu Fatima was in fact found because of such developments. A few yards away from where it was buried, farmers had hit bone with a bulldozer. After consulting with archaeologists, they agreed to halt while researchers excavated the cemetery. That was lucky, and no one has any illusions of other developments coming to a halt.

Nature is a destructive force as well. Since the 1980s, sand storms have increasingly eroded the intricately carved walls of 43 decorative Kushite pyramids and a dozen chapels at a UNESCO World Heritage site named Meroe. With funding from Qatar, archaeologists have attempted to remove sand accumulating in the necropolis. But a 2016 report on the effort reads, “the volume of the sand dunes by far exceeds all removal capacities.” An archaeologist who works at the site, Pawel Wolf, from the German Archaeological Institute, believes the uptick in erosion is partly due to droughts in the 1980s and 1990s that pushed Saharan Desert dirt northwards. Another reason, he suggests, is that overgrazing nearby stripped vegetation and promoted desertification. And once winds carried sand into the basin where Meroe lies, the sand got trapped within the surrounding mountains, sweeping violently back and forth each season.

These threats and more worry the archaeologist managing Meroe, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir, at Sudan’s National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums. Bashir hesitates to expose the coordinates of sites he’s excavating in northern Sudan — points along a putative ancient trade route to the Red Sea — because of illegal gold diggers penetrating that part of the desert. “People with metal detectors are everywhere,” he says. “It’s crazy and uncontrollable.” Already, some of the tombs have been robbed.

“As an archaeologist, you are always feeling impatient and urgent,” says Geoff Emberling, an archaeologist from the University of Michigan. “There is limited time, limited money, you are always concerned.” Before turning to Nubia, Emberling focused on Mesopotamian archaeology in Syria. He says he would not have predicted that the Islamic State, or ISIS, would eventually raze ancient temples in Palmyra, and execute a Syrian archaeologist, hanging his headless body from a column.

“Syria taught me you can’t take anything for granted in life,” Emberling says, “It could all change overnight.”

Spencer, the British Museum archaeologist excavating pyramids and neighborhoods buried beneath the sand in Amara West, prepares for loss as he works. The sand starts encroaching every afternoon. If a heavy enough storm comes through, his team’s excavations may be buried once more. And if a dam planned further up the Nile is built, it will submerge Amara West entirely. Standing beside a labyrinth of recently excavated walls just below the surface of the ground, Spencer unfolds a magnetometry map, a blueprint that guides him. He points to a spot on the map outside of the grey lines of the settlements, and then off into an ocean of dunes in the distance. The low magnetic signal in this strip, Spencer says, “indicated there might have once been a river out there.”

Indeed, Spencer has revealed how different the region was about 3,300 years ago. With Optically Stimulated Luminescence — a technique used to determine when sediment was last exposed to light — his team dated the layers of fluvial clay buried beneath quartz in the strip on the map. It reveals that Amara West was in fact an island in the Nile when ancient Egyptians and Nubians inhabited the land. By 1,000 B.C., the Nile’s side channel appears to have dried up and the island became connected with the mainland.

Spencer’s colleague, Michaela Binder, a bioarchaeologist at the Austrian Archaeological Institute in Vienna, has found that bodies buried around this point died young. “Not a lot of people made it past 30,” Binder says. Their bones are often pocked — a sign of malnutrition that Binder believes occurred as farms failed. She has also found signatures of chronic lung disease in ribs — sand and dust had polluted the air. The research suggests that the town did not end through war or poor governance, as some earlier archaeologists hypothesized, but that climate change drove people out.

Amara West is uninhabitable today because of sandstorms. Spencer’s team resides on an island nearby in the Nile. In the frigid wee hours of the morning, he and his team travel to the site by boat under an ocean of stars. They start early because by noon, winds pick up and carry in clouds of sand and small flies. In addition to documenting their findings with notes, drawings, video, and models, the team also flies kites attached to digital cameras above ruins. The camera snaps a shot every two seconds. These photos are then stitched together with thousands of on-the-ground pictures, in a technique called “Structure From Motion” that can be used to create 3D reconstructions.

Back in London, the team can input these models into the same software used to develop first-person-shooter video games. On his laptop, Spencer shows me the results. He navigates through the suburb we had visited earlier that day with the scroll of mouse. The corridors that Spencer virtually walks through are so narrow that his shoulders seem to brush against the walls. He enters a cramped room with a bust of a man with a black wig and a red painted face. It is depicted precisely as Spencer found it.

Spencer exits the virtual room and scrolls down through the floor to expose older houses that the team had discovered buried below the more recent Egyptian-style settlement. A dome appears with a yolk-shaped area sectioned off. He presses another key, and the viewer swoops high into the sky like a runaway kite. Tamarisk and acacia trees stand as they did back then, according to microscopic analyses of charcoal near the dusty banks of the Nile.

The interactive graphics are now preserved on the British Museum’s website so that people can explore them without a trip to Sudan. Digital reconstructions of tombs and pyramids from elsewhere in ancient Nubia are making their way online as well. And many of the archaeologists working in Sudan post their annual finds on blogs — their academic publications following after. The interpretation of relics may shift as well, as Sudanese archaeologists lead projects and perceive the findings through an African, as opposed to European, lens. In the near future, high school teachers might inspire students with stories of ancient Nubia, and endow those relics with all the glory bestowed on ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Perhaps the next generation of students will not think of sub-Saharan Africa as a negative space lacking history, but rather as the birthplace of humans and as home to some of humankind’s earliest metropolises, replete with governance, religion, and art.

But to piece the picture together, archaeologists will need the time and funds required to explore vast territories of arid land. Both are in short supply.

“Archaeology is always a race against the clock,” Francigny, director of the French Archeological Unit in Sudan, says. But Nubia’s losses will be most dramatic because they don’t simply supplement a known history. Instead, the findings form chapters in a new, as yet untold story. “If you want to know about a god worshipped in Nubia, you need to dig up a temple and see the iconography — that’s not like in Rome, where someone has written a three-volume synthesis on all the gods and rituals,” Francigny says.

“Every single finding is valuable because we knew nothing before.”

Amy Maxmen is a staff reporter for Nature magazine. Her stories, covering the entanglements of evolution, medicine, policy — and of people behind research — have also appeared in Wired, National Geographic, and The New York Times, among other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

this is very interesting I’ve been taking notes and I learned a lot

It’s amazing when white people acknowledge something, they credit themselves for discovering it. Research the BOOKS by African scholars =<150 yrs.

Why the museum in Egypt Cairo still does not include the Kushites as the 25th dynasty of the Egyptian Kingdom ?

Racism is a fact indeed.

Inferior complexity is another aspect of the same issue.

Two sides of a coin.

It is human nature which inherently ingrained in us !

The psychology of denial is another aspect and pathological envy too…

.w

Calling “Nubians” Black pharaohs is a back-handed way of saying the Egyptians weren’t Black or that they weren’t other “Black” Pharaohs. But how can that be when Ancient Egypt is in Africa and got its start in what is now called the Sudan. I went to school (70s) with people from the Sudan and they told my family about the Pyramids, ancient Nubia…etc.

I have to join my to those that spoke before me in expressing my profound gratitude for this very expository article.

Most often than not, things like this die away without anyone’s knowledge.

Thank you Amy for talking about the underrated pyramids in Sudan. Believe it or not, but my parents are Sudanese, but they’re from the south, which is now called South Sudan. It’s kind of crazy how in the past none of the archaeologists thought that the Nubians built and designed those pyramids. Anyways, thank you!

As an Afro-Caribbean, I feel is great to let the world know the accomplishment of African civilization, because, of all the races on the globe the one from the black continent is the less appreciated. All ethnic and/or race group had contributed to the knowledge the modern society had, and they need to receive credit for their accomplishment as well as the European have received their acknowledgment.

This is indeed an enthralling journey for those archeologists , excavators, linguistics and others to know , to discover and of course to bring the light upon the lost part of HISTORY. Its almost like fixing a puzzle without any clue. Starting a fresh with all difficulties from nature to politics. That’s why truly every discovery is important as we know nothing before.

I think it’s incredible how interracial marriage was seen as their downfall in the early 19th century. What is even more incredible is that interracial marriage was a thing then, despite racisn, the Nubian people married outside their race. As a person whose parents are still against interracial marriage, that stuck out to me the most.

It’s sad how great civilization, like the Nubian, are lost and forgotten in our textbooks and replaced with the age of colonization and slavery. Why do we want our youth to learn about the evils in humanity when they can learn about love?

Wow, what a great article thanks. I’ve been all over the Middle East and small parts of Africa. This is a great story and well researched, thanks very much for bringing it to us-

Enjoy Class, record history before its all earased

good stuff. I will make sure to bookmark your blog.

Fascinating article! Well done, Amy Maxmen. My friend, Stephanie Jefferson, wrote a series of fictional young adult novels about ancient Nubia. I’ll share this with her.

Good Information, thank for sharing

I was expecting a better quality of commentary on this Web-site instead it is brimming with juvenile pseudo-intellectual ignorance and broad uninformed statements made without references.

Quigley:

I find it SO FUNNY that you are basically dismissing Nile Valley Civilizations, because there are mountains of documentation showing that the Very Greeks you’re praising actually REVERED the Egyptians, Nubians and Ethiopians. The Greeks called them civilized, but called the Northerners, the people you descend from, Barbarians because all they knew how to do was steal [and] kill.

And in my opinion many Northern Europeans are still Barbarians because this whole global system of racism, which was created by them, is still perpetuated today and when you actually think about what it means to believe in that, it’s totally illogical. It is literally a regression in the mentality and societal norms that the most of the “ancient world” held, Greece included.

P.S. – the only reason why the Greeks were such a big deal is because we live in a globally Eurocentric dominated society. If it were dominated by Asians then the Ancient Chinese and Persians would be the big deal, etc.

Hey Golden, can you please help me out & refer me to Greek literature that explain their reverence for Nubian, Egyptian, & Ethiopian culture? I don’t know what to type into Google to get to credible sources. Thank you!

I’m a Papua New Guinea in the south Pacific and we have been colonized by western Christianity so I’m interested to know the original truth,

Thanks

Very interesting article. I learned more than I ever knew about this region.

I think, however, that when you referred to “Magnetometers” that you meant “Ground Penetrating Radar”.

The former detect changes in magnetic fields due to the presence of metallic substrates, or fields. These do NOT detect rocks, bricks or anything else that is not magnetically active.

The latter measures differences in soil density due to having been disturbed by human activity.

MY KINGDOM FOR A TIME MACHINE!

A well-researched well-presented article that takes yet one more necessary step in the ongoing process of what could be called “the optometry of understanding.” That incremental but inevitable correction of our vision of the world/universe and its history comes only with often upsetting recognition of self-centric flaw in our worldview that makes us myopically miss the inconvenient long-view truth that “WE are not the center of all that is.”

‘Brava!’ to author Amy Maxmen (and conscious commenter Nimfa,) who ideas might have been, (like dark-skinned Nubians,) dismissed as the inconsequential babble of any not upper-class males of European descent.

From Galileo’s permanent house arrest for his heliocentric heresy (“It still moves!”) to Darwin’s ‘Descent of Man’ from Divine Uniqueness, to Jefferson’s notion of ‘all men are created equal’ to Lincoln’s striking of the unspoken adjective “white, land-owning” to Anthony’s and Stanton’s successful struggles to upgrade “man” to “human” to Freud’s, Jung’s and James’ dethroning of the vaunted but imaginary ‘self’ to Einstein’s abolishing the myth of ‘absolute’ for merely ‘relative’ space and time to Bohr, Heisenberg et al discarding determinism for quantum uncertainty to Hubbell’s dismissal of our Milky Way as not the totality nor even the center of the universe but just one ordinary galaxy among at least a trillion others, smaller or larger than our own 200 billion stars, in what modern astrophysical cosmology calls “the principle of mediocrity,” i.e., “WE ain’t so special.”

The incremental dethroning of the Sistine Chapel’s White Male Center of All Creation to just one species of less-hairy ape – sometimes “the stuff that dreams are made of” but just as often “what a [nasty] piece of work is Man” – continues each year as the conceptual optometry of modern science and technology correct and extends our sight and scope. Tomorrow’s issue of Science (23 FEB 2018) debunks the persistent H. sapiens-centric view that our species alone exhibits genuine the symbolic thinking necessary for art and ‘true feeling.’ The paper by an international team of scientists, (“U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art,” science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6378/912,) uses isotopic techniques beyond conventional radiocarbon dating to determine the age of cave paintings in three Spanish sites as 64kya-66kya (thousands years ago,) conclusively excluding early Homo sapiens as the artist, since WE arrived only 40kya. That leaves one species of hominin then living in Spain at– not “WE the humans” but those Neanderthals we’ve so long dismissed as “NOT US.”

i love your lucid comprehensive commentary.

I sometimes feel we are in a race not against time but against self-destruction due to our collective ignorance.

Thanks for a detailed look at a fascinating piece of the past.

History is written by the victor at the expense of the victim. Peaceful civilizations that co-existed side by side for thousands of years were attacked and overwhelmed by a war like people who lived to conquer, enslave and destroy. Trying to debate the scientific accomplishment of ancient European society and ancient African society is the equivalent of comparing a high school P.E. teacher to Neil Degrasse Tyson. Ancient Greek and Roman ‘civilizations’ were governed by a violence dominant culture that gave birth to great armies which swept across the known world killing and pillaging. Yes these civilization had artistic,scientific, and philosophic innovation as well but the culture as a whole was resistant to forward thinking and scientific breakthroughs. We see that with the way Socrates was murdered on trial for his intelligence or even more recently the notion of a round earth was met with calls to burn the heretics. Ancient Egyptian culture worked out the earth was round a long time ago evidence is in the dimensions of the great pyramid. The funniest part of this article is that it feeds into the same thing of which it tries to speak negatively. Mentioning the intermarriage of lighter skinned Egyptians. This is a completely made up concept. One that was made up by the same archeologists that believed Negroid’s could never aspire to create such a civilization. The whole concept of a lighter Egyptian race was developed to explain the discoveries is Egypt, but as far as I’m concerned the pictures they painted of themselves as a darker people speaks volumes. The civilizations of Ancient Africa were guided by intellectual, religious, academic, artistic and scientific pursuits. The only thing that Europeans can claim superiority in is the art of killing and war. Killing all the smart people doesn’t make you smarter, it just makes you what is left.

We are all disgusting monsters. Following simple uniformitarianism, I cannot imagine that our ancient ancestors were any better or worse than ourselves. Sure the Doric invasions destroyed what appeared to be a cool civilization, but I doubt the pre-Dorics were angels. The devils among us now have bigger stones to bash in the heads of their kinder brothers and sisters.

Interesting article but could have tried a lot harder to find local archaeologists and commentators – The one local archaeologist quoted is used almost entirely to illustrate local beliefs and politics while the ‘real science’ is quoted from European and American researchers.

Could do better…

Thank you for all the work you’ve put into this article! Our vision of the past is shaped by those who write about it and for too long history was written by a few affluent white males. Any non-white, native tribes around the world were depicted as violent, naked savages by archeologist of the last and preceding centuries. I am surprised there is still so much resistance to changing that point of view, but for every negative comment that you get, know that there are many other readers who enjoy your reporting.

I’m hoping Nubian history might get more interest because of the huge popularity of the superhero film Black Panther, which is set in Africa. That would be cool as heck,lol.

Amazing the (willfull and deliberate) ignorance that abounds here. Yes, whites lied to the world and themselves and now you have whites harping about how dismissed history is somehow encroaching on their beliefs – despite their understanding of the world as being largely a myth and elaborated. It is sad to see humans behave so selfishly and narcissitic. How small and cowardly one has to be to reject findings from archeologists who wish to reveal the truth about our history instead of disonoring themseleves with ethnocentric loyalties and bias. I resent the efforts of selfish humans to distort history and push for ways to obfuscate and obliterate that which they disagree with – as in Sudan and their destructive dam. May our children replace these corrupt persons and instill best practices and interests in the name of all humanity – not just the pale ones.

If you propose Earth to be billions of years old then you must be joking when you think civilization began in Africa or Europe a few thousand years ago. There is no trace of Earth 4000B.C. except perhaps diamonds and other rocks. Stonehenge? How about Atlantis?

The oldest hominid bodies were found very long ago in Africa this is why they say civilization started in what we call Africa today. It is undeniable that the oldest humanoids traveled out of Africa.

Your holy book, which you think has all the answers to all of man’s questions, is an uncollated hodge-podge of ancient Middle Eastern mythology which you don’t even understand. But go ahead and keep hiding in the dark cave of your ignorance, you and your ilk are now completely irrelevant.

What’s with the racist subheading?

Ironic it is white scientists who are vilified for dismissing this great ancient culture.. .. where are the black scientists and where have the black scientists been ??

If you actually read the article you would’ve seen the very prominent image of a clearly black scientist who is working to help preserve these artifacts.

Steven:

It’s Black History Month—here are the pioneering black scientists whose inventions and discoveries enriched both America and the world—despite the fact that barriers were thrown in their way, and not always getting the very few opportunities open to them due to flat-out discrimination—which is what the first black scientists always were forced to deal with,regardless of their skills/talents. Anyway,you could have looked this up yourself in 2.5 seconds like I did.

https://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/scientific-experiments/10-black-scientists.htm

It is odd that our current grandiose plans to move into outer space, an incredible allien environment to all that is Carbon based

And ,Shaped by millions of years of evolution, ignores the very planet that spawned us.

Rather the learn we destroy, rather then share we hoard. Be it money ,knowledge or resources. Rather understand the limitations of

Materialism. We keep producing and polluting.

Rather intelligent well planned birth control, we birth ourselves out of house resources and our planet. Rather then make e everyone welcome we are still stuck behind the arrogance of colour.which after all is merely wall paper.

To value colour, wallpaper, over substance, makes us exactly what we are ?Horrible species.

Greedy to a point that self distruction is only matter of time .

We don’t respect what we built and are built to raze what we do not understand or refuse to understand.

Camus , now you know you are going to die ,the futility of it all. We wish for immortality not

understanding that with good evil will be immortal as well.

From Vlad the Impaler, Hitler ,Stalin ,the Pot Pal regime.

We are and will become cannibals of all that we know.

Poetic nonsense as the liberal college-knowledge bound academic cowards are know for. If we are not to forget our pasty, then explain the leftists’ attempts to erase American history by removing and/or destroying Confederate statues and assaulting our flag and even our National Anthem. Hypocrisy – thy name is tenure. Actually for living in the part of this region for 8.5 years, the problem is simple – we are holding back millions for bones…and one of their own rules the country with an iron fist. Here like in South Africa and before in Liberia point out what we back in the USA fear to acknowledge as truth – male tribalistic primitive cultural norms still prevail where the strong man rules and life is cheap. No difference here or in Chicago -genetic or just a refusal to assimilate, what does one expect.

So try preserving our own national history and identity first in the EU, UK and USA. Without our present societies and values which are under assault by the liberal NWO Nazis, none of these activities or even values would exist. Remember the Aswan dam and what that entailed – how did we save some of what was far more precious?

There are no words or sentiment to address your selfish and hateful beliefs. Extermination is still on the table for those of you who repeatedly invoke the race card, racism, bigotry, white nativism and the idiotic sense that you are somehow ‘strong’, ‘manly’, more deserving of others whose cultures stem farther back and gave birth to all we know now. I’m open-minded to deportation of such ignorance and feebleness. America and the EU would certainly benefit from the removal of your hateful species. Selfish loser.

J. Yuna:

European and American history has already been well-preserved for hundreds of years. The history of Nubia was dismissed simply because racist white archaeologists, in their ignorance and arrogance, didn’t think that black people could have created their own civilization. You sound just like them, claiming again that Nubia isn’t worth studying simply because its creators were black. I’m American, and let’s be real—you’re just another racist right winger who can’t accept the fact that white people didn’t create every great civilization in the world, or every great history, for that matter. First of all, nobody is destroying any Confederate statues—they are being put in museums. And kneeling before the flag is not disrespecting it at all. Bottom line is, the only reason we don’t know a lot about Nubia is because these white archaeologist didn’t care about it that much, and weren’t exactly trying to preserve it. But your little right-wing racist diatribe wasn’t even needed here, so move on,please.

well said.

So sad how European intellectuals decided all non whites were ignorant savages.Look at northern Europe before Roman era. They were the savages . A similar thing was done to American Indians . It is good they expose the truth . Shalom.

Indeed I know. Life as we know it began in two places – the fertile crescent of course and in Europe. I speak of Homo Sapiens and Neanderthal – because if you sequence us that bias still comes out – we get our Neanderthal alright – and if you’re African American it comes back into sub-Saharan and such.

So Stonehenge, older than the pyramids, was built by savages?

Now, now Robert. Let the critics critique. It’s a release for them, an opportunity to vent.

Robert,

Stone age does not have any architecture or a work done based on blueprint like Egyptian pyramids. Stone age does not show civilization, just a ritual place. There were no libraries with books on science and culture in Europe at the time (Egypt had the Alexandrian Library – a great loss for humanity when burned). What could you say we had in Europe at the time? We Europeans should not have thin skin because we were anticipated by civilized societies. History is history. We cannot deny it because we think we are the vanguard of the world at this moment and time. Today Europe is the one that holds the “flag ” of the modern society, but that does not imply we were ahead of other civilizations throughout the history of human civilization. We have had our moment for more than 10 decades, a moment that in 2000-5000 years from now we might not be able to hold. There might be another part of the world that will surpass us and become the new civilization that will bring our world to a higher level. That where the expression of, “The rise and the fall” comes from. Each civilized society has its moment, it rises and reaches a point when it is not able to keep up with the change the times require and unfortunately it experiences its downfall. Hopefully does not happen that way! Let’s hope that the western democracy will be capable to resist the times and help the rest of the world to rise to its standards to make our planet e better place for mankind.

Northern Europeans contemporary with Romans were savages? Because the Romans had uniforms and the North Europeans didn’t? What’s more, how do we know the Nubians were dark-skinned? Do we have images, like we do of Egyptians? And what is so great about a civilization whose largest monumental buildings are simple tombs for absolutist rulers? Classical Greece surpassed the entire ancient world in art, technology, and government in just one century.

Quigley:

The point is,Nubian history was ignored and dismissed because it wasn’t white European history—that’s why we’re still learning about what remains of its history. Did you even bother to read the article? There was more to Nubian civilization that monuments and tombs (which are a sign of a civilization,like Egypt.) Once again, you’e just dismissing anything Nubian because it’s not about white European history. How close-minded and ignorant of you.

So, you’re saying a civilization isn’t worth studying if its people aren’t white or light-skinned enough for you? Get over yourself and your stupid racism,please. This is the 21st century—that kind of thinking is so outdated and ridiculous,I have to laugh at you.

Why was the Greek learning center Alexandria in Egypt?

Because when Alexander the Great went on a conquering binge, he decided to leave a lot of cities in his trail bearing his name. I don’t see how it’s relevant.

The name isn’t important but the location surely is. The Greeks had a learning center in Egypt because that is where the knowledge stemmed from.

…. i saw the remaims of huge encampment near Gebeit – dozens of grinding stones remained there until 1995