In Defectors From the North, Doctors in South Korea Find Hope — and Data

In 1996, in the midst of a catastrophic famine, Ms. J brought her 10-month-old son to a hospital in a North Korean city near the Chinese border. Doctors couldn’t ease his terrible stomach pain, and he soon died. A few years later, she returned to the hospital with her husband, who had cirrhosis of the liver. (“He liked to drink,” she recalls.) She was newly pregnant, and he told her not to worry about him. Better to conserve her energy for their unborn child. He died, and she miscarried soon after.

Ms. J, who, like many North Koreans escaping to the South and fearful of reprisals, asked that her full name not be used, is a slim woman with black hair gathered in a rhinestone barrette. We are sitting in a small meeting room in Anam Hospital, a busy, modern university medical center atop a hill in Seoul, South Korea’s capital. I ask if she believes these deaths resulted from living in North Korea. If she and her family had lived in a different country, might some of them have been prevented?

She looks down at her lap, folding and unfolding the end of her gold scarf. “Probably all of them,” she says.

Now 46, Ms. J, who lives in Seoul and works at a coffee shop, is a volunteer in an effort like no other — a study that aims to develop a comprehensive understanding of how conditions in North Korea affect the long-term health of its people. This study — known as NORNS, an acronym for North Korean Refugee Health in South Korea — is built on a premise that will sound odd to Western ears, though it is taken very seriously in the South: that the two nations will one day reunify under one government.

When this might happen, and what sort of geopolitical cataclysm might precede it, are questions for another day. For now, a consortium of respected South Korean researchers has recruited more than 1,100 North Korean refugees, out of approximately 30,000 living in the South, whose physical characteristics, mental well-being, and other vital data are being measured and documented — all with the goal of providing a glimpse of the health care burden that reunification might one day bring.

The researchers, based at Korea University, also believe that scientific and medical collaborations can succeed where political negotiations have failed. Last fall they initiated a graduate program in public health to lay the groundwork for a post-unification health care. As the NORNS researchers wrote in their first paper, “the health of North Korean refugees in South Korea can be an important key to shaping a more positive destiny for the Korean people.”

Though its border has become porous, North Korea remains something of a black box to the rest of the world. It is glimpsed mainly through satellite images, government-approved photographs, and reports from select humanitarian agencies — or through singular moments of hostile interaction with the outside world, as with its frequent missile tests, or more tragically, the recent revelation that a young American, convicted of dubious charges in the North last year, had somehow fallen into a coma while imprisoned there and, upon returning home, died.

But studies of the health status of defectors are providing some deeper insights. They suggest, among other things, that protracted hunger and lack of access to medical services are common in the North. Some refugees arrive in South Korea with acute diseases or injuries. Others develop chronic illnesses. North Korean refugees living in the South have high rates of depression, and many show risk factors for metabolic disorders. Life expectancy in South Korea is 82 years; in North Korea, according to the World Bank, it’s 70. As a group, the refugees are poorer and shorter than South Koreans. Many bear scars — both visible and invisible — from political torture and hardship.

For her part, Ms. J was struggling to survive by the winter of 2013. It had been 20 years since the government confiscated her savings and stopped paying her to work as a switchboard operator. She had spent most of her life in a border city located in Ryanggang Province, one of North Korea’s poorest regions. At night, the power would go off and her neighborhood would fall into darkness, along with most of the country. Yet she could see lights in China, just across a thin strand of river.

It was February or March when she left for good. The surface of the Yalu River was frozen, but when she looked closely, she could see water flowing underneath the ice. She lay down as if riding on a sled to distribute her weight evenly. Then she used her arms to push forward. The border crossing took only seven minutes.

Roughly 10,000 North Koreans have slipped across the border and are now living in China, which considers them illegal immigrants rather than refugees. Chinese authorities often seek them out and deport them back to North Korea, where they are routinely jailed and tortured. When Ms. J arrived in China, she realized she was being monitored, so she did what many of her 30,000 countrymen now in South Korea have done: With the help of Chinese relatives, she paid a broker to arrange a perilous 2,500-mile journey through China, then to Laos and Thailand, where she arrived at a Bangkok refugee center. From there, she flew to South Korea, which is required by its constitution to accept all North Koreans.

When Ms. J glanced around Incheon Airport, she thought it looked like “outer space,” everything was so modern and new. And the people were so tall.

Like her child who died years earlier, she’d been having severe stomach pains even before her escape. The North Korean doctors, lacking necessary medical equipment, could not provide a diagnosis; they gave her acupuncture and sent her home. In Seoul, a metropolitan hospital identified the problem: stomach cancer. “I thought I was going to die,” she says now. “It was a surprise when the South Korean doctors told me I was going to be OK, that I could be fully cured.” Roughly a year after her arrival, surgeons removed her tumor, and today she is cancer-free.

Still, life is a struggle for most refugees. In China, their undocumented status makes it virtually impossible to earn a living. Seventy percent of defectors are women (most North Korean men work in government jobs and their disappearance is easier to notice) and some female defectors become victims of human trafficking, forced to work as prostitutes or sold as brides to Chinese men. Even if they make it to South Korea, refugees are often not equipped to adapt to its competitive culture, which values academic and professional achievement. Nor do health risks simply disappear with life in a freer, wealthier country.

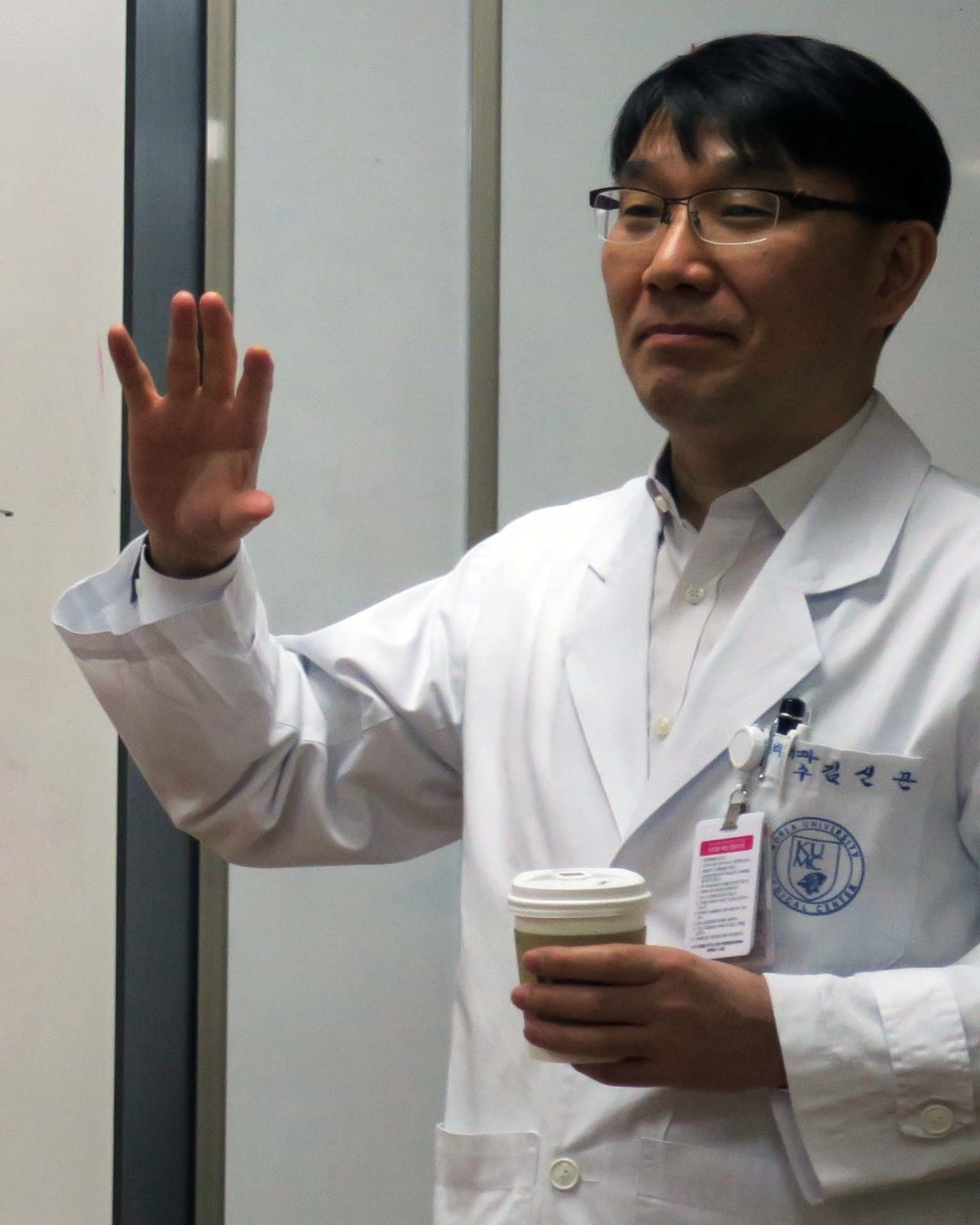

The lead researcher for the NORNS study is Kim Sin-gon, an endocrinologist and professor at Korea University Medical School. The day we met, he was wearing a white doctor’s coat and moved through the hallways so quickly I had to jog to keep up. He wore his authority lightly, joking with students and asking me to excuse his “humble” English, which he used whenever our interpreter struggled to translate medical terminology.

Born in 1968, 15 years after the ceasefire following the Korean War, Dr. Kim learned as a young child that 21 of his relatives had been herded into their church in the southwestern city of Jeonju and killed. “Among our village members, there were people who contributed to the killing of my family,” he says. When the North Koreans were forced to retreat and the South Korean military took its place, the villagers who had supported the North were killed in an act of retribution that leaves Kim shaking his head.

In the wake of the killings, many of his remaining family members became pastors. Kim quotes Isaiah 6:13 to explain: “Even when the trees get cut, the roots remain. You as people are the root, the holy seeds.” He took a different path and went to medical school. “Pastors take care of spiritual health,” he says, “but people also need to take care of physical health.”

As an endocrinologist, he’s deeply versed in what happened to the metabolism of South Koreans during the rapid economic development in the decades that followed the war. Though as a group, South Koreans are less obese than Westerners, they have a relatively high prevalence of diabetes. “After war,” Kim explains, “a pregnant woman is malnourished. Her baby will also suffer from malnutrition and the baby’s pancreas volume will be relatively small.” As the economy recovers and food consumption increases, that small pancreas won’t secrete enough insulin to support the greater calorie intake.

Kim Sin-gon, an endocrinologist and professor at Korea University Medical School, is spearheading the NORNS study. “Pastors take care of spiritual health,” he says, “but people also need to take care of physical health.”

Visual: Sara Talpos

Kim thinks the phenomenon is repeating itself in North Koreans who fled to the South. He points to his recent study showing that while North Koreans are much less obese than their South Korean counterparts, they have the same rate of metabolic syndrome, which occurs when a cluster of risk factors — such as high blood pressure and abnormal cholesterol levels — occur together, increasing the likelihood of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

These findings are especially pronounced in North Korean refugees in their 30s, who were adolescents during the famine of the 1990s. NORNS is a “cohort study,” one that tracks a group of people over time — in this case, on a first visit and then three and a half years later — to investigate the causes of a disease. Kim would like to lengthen that duration, but funding has been a challenge from the time he first applied for a government grant in 2006. With North-South tensions rising, the application was rejected, and the project has been getting by on a smaller grant from the Korean Diabetic Association and on contributions from Kim and a handful of doctors and patients.

It can also be difficult to enroll refugees. They are busy making ends meet, and many are afraid to self-identify, even to health professionals who would like to help them. And when it comes time for the follow-up visit three and a half years later, many have a different phone number. “They sometimes want to hide,” says Kim. Sometimes they move.

Despite the challenges, NORNS is the longest-running cohort study of North Korean refugees living in South Korea. Until recently, it was the only cohort study, though the South Korean government is now conducting research on refugee mental health. NORNS tracks mental and physical health, using lab tests to measure biomarkers like platelets, liver function, bone density, and vitamin D. (In one paper, the researchers report that none of the NORNS cohort had adequate levels of vitamin D.) This year, Kim opened the study to refugees under 30, and has begun to visit schools for refugee children to measure their health status.

For all of its promise, NORNS alone will not be enough to fully understand the health of North Korean defectors. Further study and resources will be necessary. Sanghyuk Shin, an epidemiologist at UCLA, served as a peer reviewer for a NORNS paper that compared the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in South Koreans and North Korean refugees. In a phone interview, Shin told me the study “addresses a very important issue in a hard-to-reach marginalized population,” but added that “it’s hard to make firm conclusions based on just this paper.” He also suggested that the study as a whole would be more effective if it supported the refugees with strategies geared toward preventing the onset of metabolic disease.

Kim agrees. In fact, last year, he applied for a government grant to study prevention strategies for refugees. His proposal was declined.

Just about any discussion of the metabolism of North Koreans — and of their health more broadly — eventually lands on the Arduous March, a term used to describe North Korea’s devastating famine, which lasted about four years, beginning in 1994. The famine was precipitated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, which had supplied cheap fuel used in agriculture. Then, in 1995, North Korea was hit by a series of floods, which destroyed harvests, emergency grain reserves, and crucial infrastructure. At the time, virtually everyone depended on a government-run food distribution program that was stretched far too thin, leaving many families to starve.

Precise numbers are impossible to pry from the closed North Korean system, but scholars estimate that the famine killed up to one million people, in a population of 23 million. “People would be walking out in public, then they’d fall down and die,” says a National Intelligence Service employee who made frequent visits to North Korea in 1998. One defector, who was a teenager at the time, recalled seeing people who had gone to the local train station to ask for food. They were lying on the concrete in rows of four and five, dying.

Ko Yoon-song laughs when I tell him I’ve heard North Korean X-ray images are so poor that a South Korean doctor wouldn’t be able to understand them. “Yes, that’s true,” he says.

Visual: Koogle.tv

Ko Yoon-song went to medical school in North Korea and became a doctor in 1998, toward the end of the famine. A tuberculosis specialist, he saw many patients with malnutrition, which compounds the effects of TB — making people more susceptible and making the disease harder to treat. Another former North Korean doctor told me infectious disease—including TB, cholera, and typhoid—was rampant during the famine. Hospitals lacked antibiotics and IV fluids, and patients ended up dying in front of their doctors.

The famine is over, thanks to humanitarian aid and the emergence of independent markets, which sell locally grown food (as well as food smuggled in from China). But many North Koreans still experience hunger and lack high-quality food. The World Food Program reports that 70 percent of North Koreans are “food insecure” and one in four children are stunted. The northeast is especially hard hit. In Ryanggang Province, where Ms. J lived, the United Nations Children’s Fund estimated that in 2009, 45 percent of this province’s children were stunted and 25 percent were underweight — among the highest rates in the world.

Dr. Ko, who defected in 2007 from a city not far from the capital of Pyongyang, felt he had enough to eat, but he lived with chronic stomachaches: Because there isn’t enough rice, the main food is corn, but it isn’t well processed and can be difficult to digest. He described a typical meal as corn with kimchi, the fiery fermented side dish, usually made with cabbage or radish. He never had meat or cooking oil, though another defector told me that wealthier families now have access to oil and rice, even meat a couple times a month.

One afternoon in Seoul, I take the subway to the War Memorial of Korea, a large museum devoted to the Korean War. Navigation is relatively easy: Subway and street signs are in Korean and English, as is the female voice that announces each subway stop along the way. Markus Bell, an anthropologist at the University of Sheffield in England who has conducted fieldwork with North Korean defectors, suggested that for insight into how South Koreans view their relationship with North Koreans, I should visit the Statue of Brothers.

The statue, prominently placed near an entrance to the rest of the museum, shows two soldiers embracing on a Korean War battlefield. The larger one is from the South; his exhausted Northern brother leans against him for support. The statue “is emblematic of how South Korea sees itself,” Bell says: “a bigger brother with a responsibility to take care of the sibling that has lost its way.”

These days, of course, brotherhood and reconciliation are a long way off. The relationship between the two countries is frozen in a state of high alert, with the North testing missiles that might be able to hold nuclear warheads. Even here at the War Memorial, a permanent exhibition showcases large military equipment — a rocket launcher, surface-to-surface missiles, and all manner of military boats and planes. Visitors are welcome to climb the equipment, and this section is filled with young kids. Examining one of my pictures, I later note that I’ve inadvertently photographed a mother and her young child standing inside a rocket launcher.

Not surprisingly, support for unification is falling, particularly among the younger generation, who experience high rates of unemployment and low wages. “Any reunification would cost so much money,” Bell says. This is why younger South Koreans are asking, “Why do we need North Korea? They’re a bunch of nuts … and they’re going to cost us a pot of money — if they don’t destroy us first.”

Why does the South need North Korea? It’s a question that Dr. Kim Young-hoon, a cardiologist and former president of Anam Hospital, has thought about a lot. Kim directs the unification public health program at Korea University Medical School, and like Kim Sin-gon (no relation), he serves on the board of the Inter-Korea Foundation for Health and Medical Education, an NGO dedicated to promoting unification by reducing health disparities between the two countries.

Kim Young-hoon believes that South Koreans can benefit and learn from inter-Korea collaboration, and that they have a moral imperative to help their neighbors. “We can’t escape what’s happening in North Korea,” he says. Koreans share a small peninsula, the Han River flows through both countries, and “the birds and mosquitoes don’t care if they’re on the north or the south side of the DMZ.”

He isn’t speaking poetically. Malaria, spread by mosquitoes, was eradicated in the South in 1979, but has reappeared along the border. Both countries have high rates of TB, albeit for different reasons: In South Korea, young people — “especially ladies,” Kim says — diet excessively, leaving them nutrient-deficient and susceptible to infection. Drug-resistant TB strains have emerged in the North, where patients sometimes abandon a course of treatment because their bodies can’t tolerate the side effects.

Thanks to vaccination campaigns funded by international organizations, some diseases have been declining in North Korea. In fact, childhood vaccination rates for measles, diphtheria, and hepatitis B slightly exceed those in the United States, according to World Bank data. But Kim says unification could hasten the spread of other diseases. “We need North Korean doctors to discuss this with us,” he insists, so that medical professionals can diagnose and treat people.

“Preparation is absolutely essential,” agrees Bell, the anthropologist. “If it all does go to the dogs and you end up with millions of people, internal and external refugees … then South Korea needs to have an idea of how they’re going to handle things like a TB outbreak.” Further, he and other experts say South Koreans needs to learn to approach North Koreans on an equal footing.

Bell believes many in the South view North Koreans in two ways: “Firstly, as 25 million souls waiting to be saved. Secondly, as 25 million potential factory workers.” Anything that deepens the inequality and makes North Koreans sub-citizens in a new unified country, he says, is likely to be met with fierce resistance.

Kim Young-hoon is one of the few South Korean doctors who has actually practiced medicine in the North. In 2000, at the invitation of North Korea, he implanted pacemakers in five patients in Pyongyang. He was shocked by conditions at the hospital, which lacked regular supplies of electricity and water; medical devices were 30 years old.

“After that, I tried to help them establish a lab like this,” he says, gesturing toward the conference room window, which frames a room full of computers. He tried for over a year to donate specialized equipment, but the American and South Korean governments feared it could be converted into weaponry.

Kim says that if the medical system is ever to be unified, true partnerships must be fostered. To that end, he has helped create opportunities for North Korean health professionals to get certification in the South. But South Korean physicians — surgeons especially — earn far more than the average citizen, and entry into the field is highly competitive. I ask him if he’s had any pushback from people who feel that these positions should go to South Koreans. Yes, he acknowledges, he has heard this criticism. At the same time, he says ruefully, many South Korean medical students are aiming at careers in cosmetic surgery: “No one wants to be a proper surgeon because it’s so hard.” He believes North Koreans might be more interested in applying for these positions.

While defecting physicians don’t need to complete medical school again, they do need to pass the medical licensing exam and then complete a residency. The exam is particularly challenging because the content is different from what is studied in North Korea, and the language incorporates a lot of English loan words. For this and other reasons, only 15 to 20 percent of North Korean physicians practice medicine in South Korea.

When Ko, the North Korean doctor, arrived in the South after stowing away on a container ship, he spent a year working as a laborer. Then he studied part time for two years, working half the year and studying for the medical exam — with borrowed university textbooks — the other half.

The practice of medicine is sharply different in the two countries. In North Korea, the focus is on infectious disease and physical trauma, often caused by coal-mining injuries. Doctors learn only the basics of other diseases because specialized medicines and equipment — chemotherapy for cancer, for example — simply aren’t available.

Ko laughs when I tell him I’ve heard North Korean X-ray images are so poor that a South Korean doctor wouldn’t be able to understand them. “Yes, that’s true,” he says, sipping a cup of coffee. We’re meeting at Steff Hotdog, a fast-food restaurant located, somewhat improbably, inside Anam Hospital. “That’s because they don’t have X-ray film.” Instead, the doctor takes the patient into a dark room, where the patient stands between the X-ray machine and a translucent screen. Ko borrows my pen to illustrate. His doctor sits hunched over on a stool like Rodin’s “The Thinker.”

With the image projected on the screen, the doctor can peer at the upper part of the lungs, where TB frequently occurs. The image quality isn’t perfect, but when considered together with the patient’s symptoms, it contributes to a diagnosis. Ko speaks with a slight North Korean accent, placing what’s called a fortis, or stress, on consonants that would be unstressed in Seoul. The North Korean accent is sometimes mocked in South Korea as outdated, unsophisticated, and irritating. But Ko doesn’t think his patients know he’s from the North — if they knew, they might be tempted to go elsewhere. When they ask where he’s from, he says China.

His North Korean patients do know where he’s from and he believes they like having a doctor from their homeland. When I respond that some defectors have told me they wouldn’t want a doctor from the North, he smiles and replies without defensiveness, “So, it depends.”

Not all who leave North Korea do so out of hunger. Park Eun-hee, a student in her mid-20s, was born into a relatively well-off family east of Pyongyang. She estimates she was arrested 10 to 15 times as a teenager for trivial offenses, such as changing her hair color. Each time she’d be taken to the police department, where she’d be held until midnight and forced to perform self-criticisms. Some of her relatives lived in China, and her grandparents taught her about the world outside. “My grandmom always taught me, ‘This country is terrible. You have to escape from North Korea.’”

Before she fled, at 22, she resolved not to get pregnant and asked a friend of her grandmother’s to buy her an IUD from a hospital, which she then inserted at home. She could have gone to a hospital for the procedure, but she didn’t want to because “I am a girl. I am not a jubu [housewife]. I am embarrassed.”

Park speaks bluntly, using English, which she has been learning through a Seoul-based NGO, Teach North Koreans Refugees: “Many brokers sell North Koreans to Chinese guys … I just thought, ‘When I go to China, I don’t want to have children.’” Fortunately, her broker allowed her to sign a contract for roughly $6,000, to be paid after her arrival in Seoul. (It took her seven months in South Korea to earn enough to pay it back.) But she knows women who had babies with Chinese men, even when they didn’t want to.

Lee So-yeon publicizes the problems of female defectors, particularly victims of human trafficking, as president of the New Korea Women’s Union, an NGO with more than 7,000 members across South Korea. She tells me that North Koreans do not receive sexual and reproductive health education. Condoms are not commonly used — a comment that came up in my interviews with multiple refugees. Some defectors arrive with syphilis; they receive treatment in Hanawon, the support center where North Korean defectors stay for 12 weeks upon arrival in the South.

The NORNS study is tracking the sexual and reproductive health of North Korean refugees, but only to share with health care providers for better prevention and treatment. The authors don’t want to increase the stigma that refugees already face. “Our whole reason for this [study] is humanitarian — helping them,” says Kim Sin-gon. “The research purpose is important, but secondary.”

As for Park, her transition to life in South Korea has not been easy. She arrived in Seoul alone and in debt. The government provides defectors with monthly support for several years, but she puts most of it toward rent. She worked weekdays and weekends for an internet-based tax company. She didn’t sleep well, lost weight, and in 2014 — roughly two years after arriving in the South — she contracted TB.

“I thought, ‘Oh, I could die,’” she says emphatically. Like Ms. J, she was surprised when doctors told her she could survive a condition that had been fatal in her native country. She was hospitalized for two days and took medication for eight months. Now she’s fully cured.

It’s worth pausing to consider the many feats Park had to achieve to get to where she is today: She had to bribe a government official for permission to travel to a border town, where she took on — and eventually paid off — a debt that is by some estimates 50 times the average monthly salary in North Korea. She risked her life traveling undocumented through China, going on foot through the mountains in Laos. She started a new life without family support. She survived TB.

Now, in her first semester at a university, she says she loves the freedom in South Korea and her access to education. She plans to study business and — eventually — study in the U.S. or Canada. “But I need English!” she says. “Ah, not yet. Take a long time.”

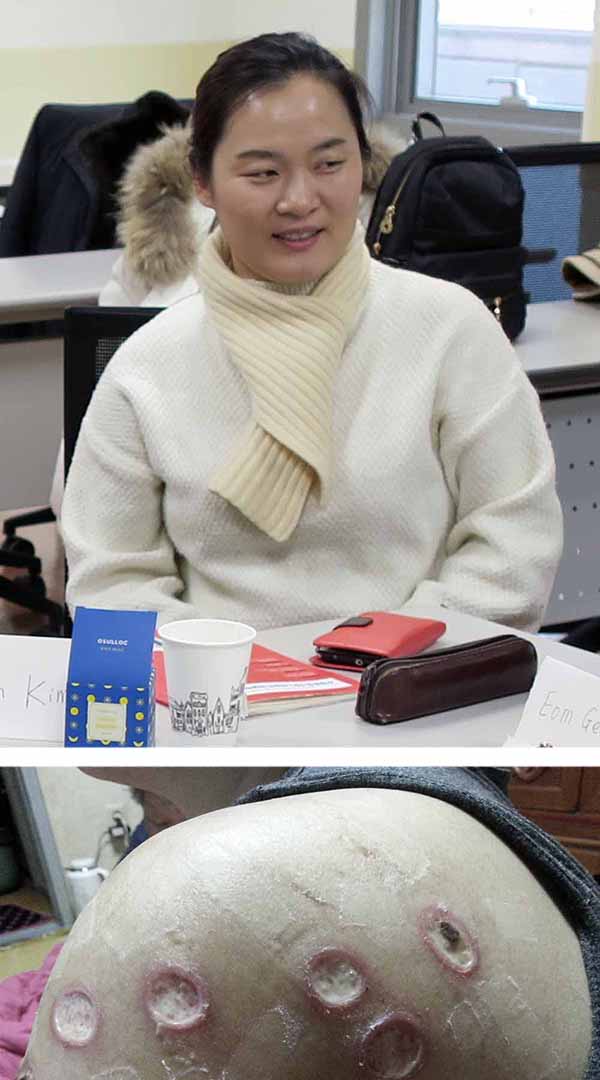

One morning, I visit Korea University to observe “Introduction to Epidemiology of Healthcare and Medicine for Unified Korea,” a class in the new public health program. A student, Kim Ock-sim (Jade), is giving a PowerPoint lecture to her classmates, an end-of-semester assignment. As a teenager, Kim escaped with her mother to South Korea. She went on to become a nurse, working in an operating room for six years until enrolling in KU’s unification program.

She puts up a slide of what look like cigarette burns — circular punched-out lesions of roughly the same size, all covered in a white milky film — and explains how they came to be on her mother’s skin. After their defection, the older woman developed shoulder pain from sewing, and physical therapy didn’t fully resolve the pain. So she treated herself with a traditional Chinese therapy: burning dried mugwort on or near the skin.

North Koreans are used to treating themselves, she says. It’s an impulse that doesn’t just disappear, even with access to thoroughly modern care. As it turns out, her mother is convinced that this rather painful-looking treatment did relieve her pain. “But,” Kim says, smiling, “as a nurse, I can’t support this.”

North Koreans are used to treating themselves, says Jade Kim, top, who escaped as a teenager to the South with her mother. Such impulses often stay with defectors — including with her mother, who inflicted these wounds on herself while treating a sore shoulder.

The story is a reminder of the sharp differences between the two nations’ health care systems. Because of lack of access to Western medicines, North Koreans rely heavily on traditional Chinese medicine. In theory, medical care is free and accessible to all, but in practice, people usually need to pay a bribe for care. And even large hospitals require patients to obtain their own supplies from the jangmadang.

Jangmadang (meaning “marketplace”) emerged during the famine when North Koreans took up illegal market activities to make money and obtain food — and, later, manufactured goods and medical supplies as well. Park explained that some doctors finish medical school but don’t work as doctors because they can’t get paid by the government. Instead, they start their own businesses, selling medicine, IV fluids, needles. Folk remedies are also sold at the market. As a result, when many North Koreans get sick, they don’t go to the hospital; they go to the market.

Researchers, too, have learned to work without access to advanced technologies and so-called Western medicines. Kim Sin-gon and his colleagues recently analyzed more than 2,000 internal medicine articles published in North Korea from 2006 to 2015. (These papers are not readily available to the outside world, and when I ask Kim, he tells me he can’t reveal his sources.) A summary of their results was published as a correspondence in The Lancet.

It turns out that their researchers in North Korea are studying some of the same natural substances as researchers in the South, but the North is further along. “It’s important not to ignore these folk remedies and natural treatments,” says Kim, citing the 2015 Nobel Prize for Medicine, which was awarded to three scientists who helped develop drugs to combat infectious diseases such as malaria and river blindness with substances found in soil and plants.

Ko also believes South Korean doctors can learn from North Korean doctors: “South Koreans doctors don’t use the basic tools, a stethoscope for example, or — even more basic —their hands for touching and their eyes for looking at the patient’s emotions,” he says. Instead, they mostly rely on machines like CT scans and ultrasounds. Some of this has rubbed off on him, he acknowledges: “I’ve become more like a South Korean doctor, but I still have some of that North Korean practice remaining in my hands.”

Of course, CT scans are more accurate than hands and stethoscopes. Yet he feels that doing both together allows him to come up with a more accurate diagnosis.

Sitting in the classroom at Korea University, I wonder if I might be witnessing the beginnings of a new health care system, shaped by Koreans from both North and South. The future of the peninsula is uncertain — no one knows how things will change under the new South Korean president, Moon Jae-in, nor whether the North Korean dictatorship will bomb the South, reconcile peacefully, or collapse under its own weight. Without a clear path forward, everyone is trying to see in the dark.

And North Koreans are used to that. In an email exchange with Jade Kim, I ask out of curiosity, what nights were like without electricity in North Korea. Her answer: “On winter nights, when the snow is falling and the moon is shining, we can see the world around us.”

Sara Talpos is a freelance writer whose recent work has been published in Mosaic and the Kenyon Review’s special issue on science writing. Sara has an MFA in creative writing (poetry) and is interested in the connections between science and literature. She taught writing classes at the University of Michigan for ten years.

The author would like to thank Grace Jo, vice president of the organization NKinUSA, for her help in the early stages of this article.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I wondered what happened with the Phase II results… I hope that there will be a report on the original participants soon. I could not agree more that true unification, where both sides realize the assets of the other, would be a beautiful thing. The assumption that –“of course”– North Koreans will want to be in South Korea ignores the question of why some return to their native country. The solution to the modern rat race of South Korea (so much worse than most of us in the US might realize) could well be answered by their Northern counterparts who actually take the time and have the opportunity to see the stars at night.

This is truly fascinating, and makes me wonder why more scientists have not looked at this cohort. The lack of availability of Western Medicine, and people resorting to ‘Traditional Medicine” makes it a good area for study. i found it interesting that the NK government provides Acupuncture, a scientific study there can show it’s effectiveness or lack of it. The US is forcing the poor and low income population to seek out these same kinds of remedies, adding to the death rate. The effects of starvation and deprivation on Epigentics, could be another area of study. The findings here must not be popular or they would be trumpeted by the US media. The idea of the “Marketplace” one that is being promoted in the US, as an affordable alternative can be evaluated too. It looks like the Traditional Medicine has not improved longevity, or counteracted the effects of no healthcare, or healthcare so limited, it is barely recognizable.

I simply wished to thank you so much again. I’m not certain the things I could possibly have created in the absence of the entire tips shared by you

concerning my situation. It seemed to be a real daunting difficulty for me,

but witnessing a skilled avenue you handled it took me to cry for contentment.

I will be thankful for this assistance and even hope you recognize what an amazing job you

happen to be getting into instructing some other people all through your webpage.

More than likely you haven’t got to know any of us.

This is a well written article from a different perspective. You can get an idea of the problems of unification if you look to the beginning of East-West Germany after the wall came down in 1989.

Wow! Reading on the internet, u often have to give up good spelling, intellectual subjects, deep thinking, etc. It was SUCH A PLEASURE to read an article so well put together, and so comprehensive! It never occured to me that bringing the north and south together could be so difficult and could involve so much. As someone else mentioned, the more time goes on, and the more the two sides are different than similar, it seems the harder reunification will be! Rather than the northerners just having an accent, they may eventually speak an entirely different language! Coming together needs to happen sooner rather than later. Fantastic read! Thank u!

Sara Talpos, you did very fine work on this article. I read every word with admiration for your writing skills.

Only wanna remark that you have a very nice web site, I love the design and style it really stands out.

Hiya, I’m really glad I have found this information. Nowadays bloggers publish just about gossips and web and this is really frustrating.

A good site with exciting content, that’s what I need.

Thank you for keeping this site, I will be visiting it.

Do you do newsletters? Can not find it.

A very well-written, informative article. Thank you for your effort.

With the coming war they are certainly going to need good health care!

Really interesting read. As time goes on and new generations of South Koreans become more detached to relatives they may have in the North, I think reunification becomes increasingly less likely.

That said, such a reunification will no doubt be a monstrous economic burden on the population in the South. There’s a need for medical care, basic education, social supports, food, infrastructure.

Very interesting to see the kind of data medical researchers are able to extract from defectors though. Provides a glimpse into what might be needed if the peninsula does one day come together.

Fantastic article! There are so many different problems with uniting the two countries. I never thought about the medical or education angle of it.

Excellent article. Thank you.

Thank you for this very interesting and well-written article!

OUTSTANDING article!!!

I concur. It is such a joy to read a really well put together article like this. I never comment on articles, but I wanted the author to know how much I enjoyed.