Paper Trails: Living and Dying With Fragmented Medical Records

It was a cool April day in 2016 when Michael Champion’s wife, Leah, noticed that her husband’s forehead was drenched in sweat. She took his temperature and couldn’t believe the number: 102.4 degrees Fahrenheit. He had been lying in bed more often, and as she watched him over the previous weekend, she’d hoped he would improve. But when Michael became so weak he couldn’t even hold up his head, she knew this couldn’t wait any longer and she called an ambulance.

I was a first-year resident working at the Palo Alto veterans’ hospital when I got a call to evaluate an elderly vet with fevers. Michael was not able to tell me his symptoms. From his chart, I gathered that he was a longstanding diabetic. He’d also suffered a stroke several years earlier that left him with a weak right side, slurred speech, and trouble swallowing. He had a permanent feeding tube and required bladder catheter insertions several times every day. Stripped of the ability to interact the way he could before his stroke, he spent most of his time in bed or in his wheelchair. Leah was his primary caregiver.

Now she sat by his bedside, coloring in the details of a medical history he was unable to voice himself. She told me how tired and disoriented he seemed. He was pale. It wasn’t right.

I ordered blood and urine tests that traced his fevers to a multi-drug resistant infection in his bladder. We treated the infection with antibiotics and worked on techniques for hygienic catheterization. Because of the infection, his blood sugar ran consistently high, so we also added extra insulin to his diabetes regimen.

He was doing better within a few days and his mental status had perked up. Every morning, when I asked how he was feeling, he was able to provide one-or two-word answers. Several times he gave me a thumbs-up.

INTERVIEW: Hear the author of this story, Ilana Yurkiewicz, discuss how it came about with veteran science journalist and director of the MIT Graduate Program in Science Writing, Seth Mnookin.

But his hospitalization had taken a toll — especially on Leah, who now realized Michael would need to regain his strength for her to care for him at home. He could hardly move from his bed to a chair without two people assisting him, and even that left him drained. Our case manager identified a skilled nursing facility nearby, just south of San Francisco, with continued physical therapy and around-the-clock nursing care. I remember Leah expressing relief about the choice. She would be able to visit him every day but still rely on a dedicated team of professionals to help him until he fully recovered.

I performed the rituals of hospital discharge that had become second nature to me as a resident. I typed out a discharge summary outlining each of his medical problems. I spelled out his antibiotics plan. I wrote his new insulin regimen — an additional injection every six hours and extra doses with his tube feeds, on top of his usual morning dose. I summarized what we were thinking, what we had done, and what needed to be done next. Whenever possible, I had learned to bolster that sheet. I used simple and straightforward language. I bolded. I double-checked my medication list. I knew this sheet was often the only guidance a nursing facility would receive. If I didn’t write something here, it very often didn’t exist.

But I also knew that even if I did write it down, it might not be read by the caregivers and health care professionals who would treat him next. And I knew that only fragments of their notes and charts were likely to get passed down the line of Michael’s care, too. And that’s precisely what happened. Over the next few weeks, Michael would return to my hospital more than once, in bad shape thanks to unconnected records that were not easy to transfer. In one instance, he didn’t receive the insulin doses that I had so carefully marked in his discharge form, which left him in a near-comatose state.

Michael isn’t alone. Every year, an untold number of patients undergo duplicate procedures — or fail to get them in the first place — because key pieces of their medical history go missing. Countless others suffer from medication errors. Hospitals, nursing homes, and other medical facilities use a patchwork of methods to track records, relying on proprietary technology or old-fashioned communications such as faxes and paper notes. These systems don’t always sync, and the collective costs to patients, hospitals, and the economy as a whole are impossible to quantify — although some experts say consistent and cohesive health information technology could save billions of dollars. An initiative from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services aims to unify these disparate systems, but we remain far from a universal electronic medical record that would solve the problem.

Meanwhile, we have stories like this one, which is a story about gaps. Michael would slip through these gaps. But as I filled out his record for the first time that day in 2016, neither Leah nor I knew just how short our best efforts would fall. Back at the hospital, she and I shook hands and she thanked me for my care.

More than a year and a half later I would ask how Leah had felt at this point. She said: “I had my concerns about him leaving.” But we had faith in the system and she was relieved her husband would be in a skilled nursing facility, receiving help for medical problems that had become too overwhelming for her to manage alone.

He would get stronger soon, she thought. Then, they’d be able to go home.

The American health care system is dynamic by design. Patients move from one hospital to another; from a hospital to a rehab facility; from the wards to the intensive care unit (ICU); from the hospital to a primary care setting. These transfers are inevitable, as a person’s health either improves or declines, or if that person simply desires a second opinion. In non-emergency situations, it’s somewhat of a medical free market. Patients have every right to take advantage of it. But when the patients move, their histories often lag behind.

When I meet a new patient, I have to gather slips of these histories from various sources — electronic records, paper documentation, outside faxes, notes in wallets, family members — to piece together a meaningful narrative. Why is this person on a steroid medication and is there a plan for tapering? Is this poor kidney function new? How had Michael’s fluctuating blood sugar been managed when he’d been sick before?

While most hospitals in the United States today use electronic health records, they remain disparate, with hundreds of different interfaces and minimal data sharing from one care facility to the next. Today, less than half of hospitals electronically integrate data from other hospitals outside of their system, and only 30 percent of skilled nursing facilities share data outside their walls, according to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Without an easy way to get a patient’s full medical files, I must ask where their prior doctors were, have the patients sign a release form, fax it to the other hospitals, and receive stacks of papers in return. Then I dig in. Unable to use control-find on a stack of paper, I sift through several to hundreds of pages to find the few values of importance. If I’d like to see images, such as MRI or CT scans, it’s more involved: I request CDs, wait for them to be mailed over, walk them to our radiology department, fill out another form, and then wait another day or so until I can see them in the computer system. The more places the patients have gone, the more there is to unravel.

When a patient with a complex medical history like Michael arrives under my care, it’s like opening a book to page 200 and being asked to write page 201. That can be challenging enough. But on top of that, maybe the middle is mysteriously ripped out, pages 75 to 95 are shuffled, and several chapters don’t even seem to be part of the same story.

Meanwhile, everyone around me is urging: write now.

Mere days after the Champions left, my senior resident asked me to evaluate a new patient. He had a history of diabetes and stroke, and he was so tired he couldn’t keep his eyes open. “Admit to medicine,” the note from the emergency room had read. When I pulled back the curtain, my heart sank. The patient was Michael Champion. His frail body lay still in the hospital bed, eyes closed, unable to communicate. When the emergency doctor gave Michael’s sternum a brisk rub, he awoke only to instantly fall back asleep.

Leah was next to him, her face contorted. She told me that things went wrong the moment they had arrived at the nursing facility. The scheduling of his tube feeds was disrupted by the antibiotics regimen. The extra insulin I had written in his chart had also been withheld.

A blood test revealed one likely source of Michael’s lethargy: his blood sugar was nearly four times higher than normal. A reading just slightly higher can tip a diabetic into a condition called hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, with risks of extreme dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and in the worst cases, brain swelling. Though the latter is rare, its mortality rate is high. I spoke to Leah at the bedside. Incredibly, she wasn’t angry. She knew it was a fixable problem and she relied on us to fix it, just as we had his infection. But she was confused. The entire time he was in the hospital, he was given extra doses of insulin every morning, afternoon, and evening. At the nursing facility, he had been given none. How could this have happened?

Leah’s question gets at the million-dollar one: Why?

The answer lies in the tangled evolution of e-health technology. In 2004, President George W. Bush created the ONC within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In 2009, Congress then authorized and funded related legislation known as the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH) to stimulate the conversion of paper medical records into electronic charts. And indeed, many hospitals and doctor’s offices did this successfully, says Karen DeSalvo, the National Coordinator from 2014 to 2016, by “digitizing the care experience of every American.” But each electronic health vendor made proprietary systems that weren’t always compatible with one another, which made it hard for records to transfer between medical facilities. Now, says DeSalvo, “we need to get them blended.”

In 2014, DeSalvo’s office had about $100 million to hit this goal. But even with this level of support “that kind of transformation is difficult,” she says. There are hundreds of different vendors using diverse technological platforms, each with a unique way to organize patient data. Finding a universal way to blend the systems has been a bureaucratic and engineering nightmare. Sometimes, the barriers are intentional, DeSalvo says, as vendors don’t necessarily want to make it easy to share data with hospitals using competitors’ systems and may charge them a fee to do so. Blocking also occurs because of a misunderstanding of patient privacy rights. As efforts to exchange data go public, some critics worry about security leaks.

The handwringing over privacy may not be necessary. According to Lucia Savage, a lawyer and the former chief privacy officer at the ONC, the same privacy rules apply no matter how patient files are shared — whether by handwritten notes, faxes, or electronic files. “Doctors, nurses, physician assistants — they have ethical rules,” she says. “They’re not supposed to be snooping around someone’s data because he’s Steve Jobs…We have to assume people act professionally and ethically in this space.”

For patients, the trust often already exists. When anyone comes into any health care facility, we review all the records we have. Together, we openly discuss and dissect deeply personal information. In fact, patients may be the biggest advocates for sharing medical information, says Mark Savage, director of health policy at the University of California, San Francisco’s Center for Digital Health Innovation. (He’s also married to Lucia Savage.) Patients tend to take it for granted that their doctors are talking to one another, he adds, and “they’re frustrated when information is not exchanged.”

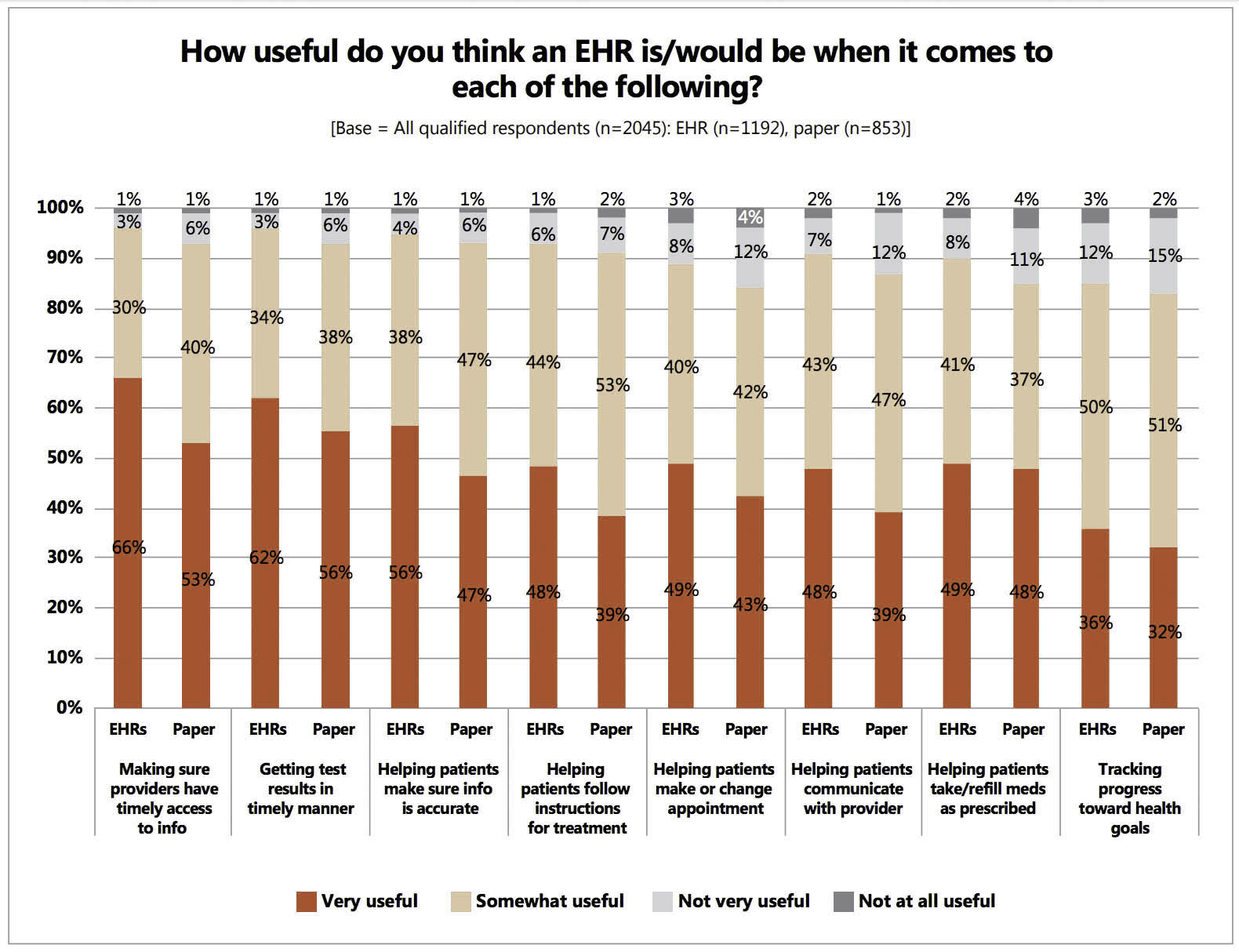

There are data backing up these ideas. A 2014 survey of more than 2,000 patients by Mark Savage, then with the National Partnership for Women & Families, and colleagues showed that 95 percent felt electronic records “were useful in assuring timely access to relevant information by all of their health care providers.” And more than three-quarters said they already share information with their health care providers all or most of the time. Those who used electronic records compared to paper records reported more trust in their providers to protect privacy.

These results resonate for me. Over my last few years as a doctor, I can’t think of a time when a patient complained that a doctor knew too much of their medical history. Yet many times, I’ve heard frustration that we don’t know enough.

In the absence of a system that reliably transmits information, we get creative. When the system fails to fill in the cracks, we hope the patients can help. I ask them: What did the doctors say? What did the testing show? Was it a loud machine where you lay flat or did someone use a probe coated with cold gel?

When patients don’t know, the burden of creativity falls on motivated bystanders — sometimes other health care providers or family — who, through grit, persistence, and clever workarounds, find ways to cobble information together and pass it forward.

Michael Champion was fortunate to have a living, breathing medical record in Leah. Early on when we met, I noticed how she pulled from a purse a yellow legal pad. Later, I learned that the pad accompanied her wherever Michael went, and she used it to jot down the minutiae of his care. She spoke with a deep knowledge of his medical issues and hospital staff would often ask her if she was a doctor or nurse. No, she would say. This was a role she had acquired out of necessity.

By the time we lowered Michael’s blood sugar and he was ready to be discharged for the second time, I learned my lesson. I had performed my rituals of discharge diligently. But I needed more safeguards. When in doubt, duplicate. I had a plan, and it had three parts. One: I would print my discharge instructions, as before. Two: I would call the nursing facility and verbally pass off Michael’s care plan. Three: I would rely on Leah. As the only source of continuity in Michael’s many transitions, Leah would be the glue. If everything else fell through, she could advocate.

Many patients don’t have a Leah, though I’d seen a lucky handful who had people go above and beyond to fill in the gaps. There was the oncologist who needed the biopsy results for one of her new cancer patients. The biopsies had been done long ago, at another hospital, and the patient couldn’t remember who had done them or what they showed. So the oncologist cold-called all the physicians in the department; when none of them knew the patient, she asked for the names of all the recently retired doctors and called them, too, until she got what she needed.

I also remember the Italian man whose clever physician spared him an invasive procedure into his heart from 6,000 miles away. The monitors capturing the man’s heart rhythm showed ST elevations — the scary sign of a serious heart attack colloquially known as the “widowmaker.” The patient saw the concerned looks on our faces as we watched his monitor and then calmly reached into his pocket and pulled out a folded paper that had been cut to wallet size. It was an old rhythm strip, labeled 10 years ago, and it had the same ST elevations. His primary care physician had told him to keep it on him at all times, so that any new doctor would learn he had an irregular baseline and not wheel him straight to the cardiology lab whenever he walked through a hospital door.

I thought of these stories on the morning of Michael’s discharge. He was headed to a different nursing facility, about 10 miles south of the first one. I spoke to Leah candidly. I told her disappointing truths: Discharges are the most dangerous times of a hospital stay and I had seen plans break down even at the best institutions. Because of that, I said, I am going to tell you the details of his medical care. The nursing facility should already know these things. But if things go wrong, you can fill in the gaps.

It was unfair. Beyond dealing with the emotional weight of Michael’s illness, I was asking her to carry his nuanced medical care as well. I was asking her to perform the jobs that the medical system around her was supposed to do. But no one was incentivized to care as much as Leah and she took on the challenge with enthusiasm.

We spent the next 30 minutes talking shop. She asked questions. I answered them. She took notes on her yellow sheets. We brainstormed, together.

“I want to empower you to advocate for him,” I said.

She put down her legal pad, reached out to shake my hand, and then, reconsidering for a moment, instead softly wrapped her arms around me for a long hug. She was about to head into the medical unknown.

The next time I saw Leah, she sat by her husband’s side as he lay in a hospital bed again. It was one week later. We were in the ICU. She rose from her seat when she saw me. With every visit, I swore I could see new wrinkle lines. It was as though she was in a time warp, aging a year through every week of her husband’s medical decline.

“It was like you were prescient,” I recall her saying. “I did everything you said, and it still didn’t work.”

This time, the gap was in Michael’s tube feeds. Through his feeding tube, he was meant to receive both nutritional formula and water. Water is critical to balancing electrolytes in the bloodstream; without it, the relative sodium levels in the blood can rise. The cascade of side effects increases as the sodium does: confusion, seizures, coma, death. But the second nursing facility hadn’t given Michael the right amount of water. His sodium soared and, once again, he was nearly comatose.

Leah had alerted the physician. This is completely different, she pointed out. He’s not speaking. To which she said she was told: This is just progression of his illness. He’s a sick person, you know.

But Leah was right — though she didn’t know just how sick Michael was. She came back from running errands shortly thereafter and found Michael being loaded into an ambulance. In the emergency room, his labs showed a sodium level nearly 20 points higher than the upper limit of normal. It was infuriating. Michael was now in the ICU, less than three weeks after he was admitted and discharged and admitted and discharged again. It was preventable.

Leah’s question was potent: “How could this have happened?” At the time, I imagined many possible answers. Maybe my printed discharge summary had gotten lost. Maybe his initial nurse left it out during a verbal handoff — where the responsibility for care is transferred from one provider to another — to be forever erased from his history.

More likely, a nurse or doctor had held a handful of pages in their left hand and a handful of pages in their right, trying to re-create a medical story from scratch. And the details of his sodium management were lost in the shuffle.

In 1999, the Institute of Medicine, now called the National Academy of Medicine, published one of the most famous reports in medical history. “To Err is Human” noted that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die in hospitals each year from preventable medical errors — a figure that was later compared to the equivalent of a jumbo jet crashing every day. More recent studies suggested this number was too low, raising it to more than 400,000 deaths per year. If they were a disease, medical errors would now rank as the third leading cause of death in the United States, a 2016 analysis published in the BMJ found, right behind heart disease and cancer.

I wanted to find data on errors that occur as patients move across systems. What is the cost of these transitions? I imagined both errors of commission — of repeat lab tests, scans, and even procedures — along with errors of omission — delayed or missed diagnoses because of an incomplete medical context.

The data we do have is unsettling to read. The Joint Commission, a large accreditor of health care organizations with a focus on patient safety, studied transitions of care and concluded that they are largely ineffective, leading to adverse events, hospital re-admissions, and soaring costs. Their conclusions were supported by several key studies. One reported that nearly 20 percent of patients experienced adverse events — like Michael Champion’s sugar and sodium spikes — within three weeks of discharge. Almost half were deemed preventable. And when patients are admitted to hospitals, more than half have at least one discrepancy in their medications.

How much is faulty record sharing to blame? My colleague, Marta Almli, an internal medicine doctor, surveyed the resident physicians at my hospital and others and found widespread dissatisfaction with how we obtain medical records: among 58 physicians surveyed, 81 percent said it was “somewhat difficult” or “extremely difficult” to get information about patients who transferred from another health care facility. This was, notably, in spite of a majority of the same physicians saying they had a “good sense” of how to get transfer materials and reporting that they regularly evaluate a new patient’s file when that person arrives under their care.

When the system fails, leaders in medicine suggest some tricks for improvement: better documentation, better verbal handoffs, and double-checking it all. The advice usually amounts to this: When the system fails you, be more careful. Work harder.

And so we do. But on a large scale, it breaks down. We can do every one of these steps and more, but stories like Michael’s will persist because humans are fallible, memories are fickle, and it’s an intellectually gargantuan task to distill decades of history in a few sentences.

We can cold-call retired physicians from distant hospitals and we can print rhythm strips to stuff in wallets. Something relevant will eventually go missing. Maybe not this time, and maybe not the next. But as an aggregate, this can’t be counted on as a backbone system of safety. It’s also a waste of resources to rewrite a new chart every time a patient enters a new building. I’ve seen doctors go above and beyond in every possible way and yet I’ve seen how hard it is to always get it right. It’s as engineer W. Edwards Deming said: “A bad system will beat a good person every time.”

When hospitals share information, care for everyone improves. Researchers at the University of Michigan found that when emergency rooms shared files, it was far less likely for patients to have repeat CT scans, ultrasound, or chest X-rays. Another study, from Israel, found that sharing health data compared to looking at only internal data cut down on redundant hospital admissions.

Slowly but surely, hospitals are venturing into data sharing. For instance, one of the most widely used electronic health vendors called Epic has a “Care Everywhere” platform, which helps facilities share electronic patient records quickly and efficiently. More recently, the company upped the ante with a “Share Everywhere” tool, giving patients control to share their health data with doctors anywhere in the world. Care for veterans improved when the electronic health record system VistA (Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture) included a tab for sharing data from one veterans’ hospital to the next anywhere in the country.

These are powerful steps. But many experts see the last frontier as a universal electronic health record accessible across all hospitals and patients. Such a health record would transcend institutional borders. It would mean no more creative workarounds. No more paper faxes. No gaps.

Michael’s medical team eventually corrected his high sodium and, after two months of rehab, Leah finally took him home — with hospice services. Generally, in order to qualify for hospice, a doctor must certify that someone has six months or less to live. But sometimes when we cut out the aggressive medical care, amazing things happen. Some people live longer.

Such was the case with Michael.

On a windy afternoon in January 2018, nearly two years after I first met the Champions, I saw them once more, this time at their home. Michael was doing well, considering what he’d been through. Leah had decided to do Michael’s insulin and water herself, and she also had nursing aides come visit the home four days a week. In the end, she trusted herself most. She was the pillar of continuity Michael needed — that many others do not have.

During my visit, I told Leah that I never found out exactly where the breakdown in communication happened at the nursing facilities nearly two years ago. I retraced their steps and paid visits to both, trying to recreate their story. Along the way, I found no electronic trail of Michael’s stay. There were some records, but for discharge patients they were stored in a paper binder in a separate storage facility.

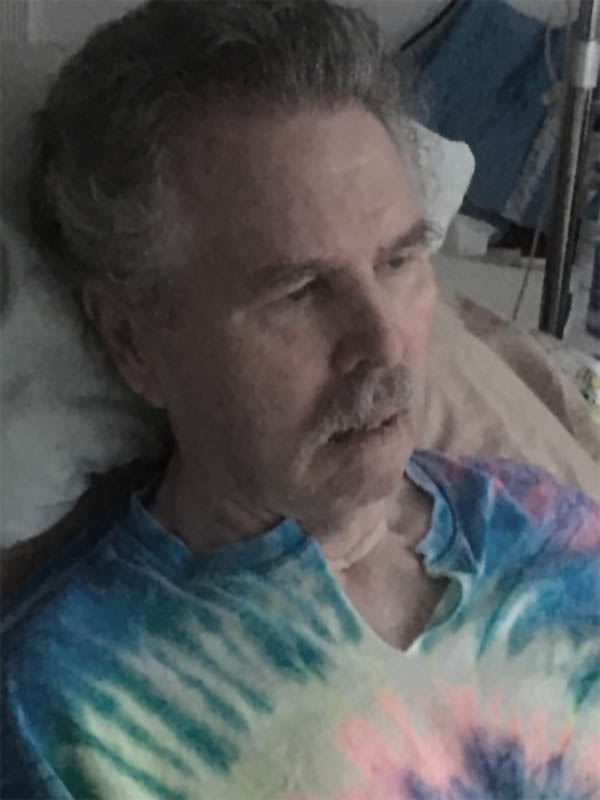

Michael Champion in July 2018. “His gift to me was clarity,” Leah said, adding that his last words to her had been: “Let it go.”

Visual: Courtesy the Champion family

I sat with the admissions coordinator at one of the nursing facilities as she ran me through the process. How they obtain records depends on where the patient is coming from, she explained. Some places send electronic forms and some go through fax. What arrives is a standard set of papers: the physician’s discharge summary and the most recent medication list. The nursing facility doesn’t receive a full set of lab values unless the physician copies them into the discharge summary, or any notes prior to the hospitalization, such as primary care records.

I wish finding the hole was simple: a broken fax machine; a paper chart that ended up on the wrong desk. But when the process is roundabout, requiring multiple steps and multiple workarounds, the breakdown points multiply. Sometimes, it’s remarkable that things turn out well so much of the time, given all the places they could go wrong.

Michael had more fortitude than almost anyone I’ve met. He recovered, again and again — sometimes because of, and sometimes in spite of, his medical care. But six months after my visit, just this past July, Michael died — on his own terms. He’d had pneumonia and it showed signs of coming back. Leah asked if he wanted to treat it or have nature take its course. “His gift to me was clarity,” Leah told me later. “I didn’t have to make the decision for him.” Michael’s last words to Leah had been: “Let it go.” She brought in family and friends to say their goodbyes. Then they stopped his tube feeds.

Since then, I’ve thought back to my last visit with Michael, when Leah asked if I’d like to talk to him privately. When we were alone, I asked him: “Are you happy?”

Michael looked out the window and then turned back to me.

“Yes,” he nodded.

I nodded back, reflecting on what it was like to reconstruct the entire human narrative of Michael Champion from a handful of scattered, disconnected fragments. As I looked at him, I saw all my patients, and I thought of how to get them the informed medical care they so deeply deserve. I eagerly await the day a universal electronic health record connects the dots. But it’s not that day, so we in the health care system must do everything in our power to deliver good care to those who trust us with it. We will continue to push papers through fax machines, to wait on hold as we cold-call those who may provide answers, and to repeat tests from scratch when we’re stalled.

We know it’s not a perfect system. We know there will be gaps. But what choice do we have?

Ilana Yurkiewicz, M.D., is a physician at Stanford University and medical journalist. She is a former Scientific American Blog Network columnist and AAAS Mass Media Fellow. Her writing has also appeared in Aeon Magazine, Health Affairs, and STAT News, and has been featured in The Best Science Writing Online and on CBC/Radio-Canada.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Several years ago I started PAPER CHARTS for my entire family. My charts look almost exactly like the paper charts that every medical facility had BEFORE they went digital. I use 14 point stock manilla folders with fasteners and a two hole punch. I have color-coded sections for labs, x-rays, lists of medications, physicals, progress notes. I bring the chart with me to their medical appointments and ER visits. I keep it safe in my file cabinet. I STRONGLY URGE everyone to use this system. I get print outs from every medical visit and when I get home, I two- hole punch and fasten it inside my folders.

I work for a medical records copy company.

I process requests for medical records not only for continued care but for litigation, work comp, and Insurance claims.

Even the sites that have the same electronic medical records are different.

To find records they must be categorized correctly otherwise an initiated search will not see them. Records from outside the site can be labelled in a bewildering number of ways making them difficult to see.

Today I was accessing a paper chart that was scanned into EMR.

The person who had scanned the chart in had used the date of the scan instead of the date of each record that had been scanned making one open each pdf file to ascertain

what it was. I cannot image the frustration MDs must feel.

CollectiveMedical.com is the largest U.S. care collaboration network, they connect disparate systems across the care continuum. Collective share’s pertinent health information with care team members in real-time at the point-of-care. All health care institutions need to connect to their network.

i’m a primary care doctor in marin county, california. i’ve been using touchworks by allscripts (one fo the biggesst EHRs in the country) for over a decade. tho’ it has a lot of “features,” when it comes to getting information into or out of it, there are issues.

for example, a new patient may have a USB drive containing important records. i’ve been told the only way to get those into our system is to PRINT EACH PAGE AND SCAN IT IN!! (i am not making this up).

if i have a patient who tells me they returned from a vacation in, say bora-bora, and i read a month or so later that there’s been an outbreak of a disease there, it’s IMPOSSIBLE to search the text of my note (i dictate notes into dragon dictate with the patient there and give them a copy when they leave) that mentions details like this. despite the note being just text, the non-relational flat-field proprietary database that i’m told allscripts uses makes this impossible.

i’ve been using computers since 1965. when i took fortran 4 in undergrad. i know what they should be able to do, but they can’t. i’d be willing to share my ideas, but am pessimistic anything will change. until things get straightened out, ask your doctor for copies of everything (on paper) and hold on to them.

I have spent the last five years of my life building a solution to this problem; the middleware, the data highway and the healthcare commerce hub

between EHRs, patients and all their care providers. It is called AZOVA.

Timihealth is working with medical organizations to place their medical records on the blockchain, making them available and secure for everyone. Please look into it.

In the past year, I’ve been involved in a struggle with the military to obtain medical records for my husband, who was admitted to a hospital for several problems. He no longer had a paper copy of them, and according to anyone I speak to…they simply don’t exist. The first visit, we were sent home with blank discharge papers. No instructions for follow up care, no record of received treatment.

Since then, I have been keeping my own paper records, but it becomes increasingly difficult to keep track of what is pertinent information, and what is to be discarded as temporary or unrelated to other issues. With every visit, you add a page or two, never really knowing if it’s going to be useful, insisting on being given copies of discharge and treatment records. I find myself relying upon a family member who is a nurse to vet the papers for me, but even then I’m afraid to throw the rest out, I just don’t carry them with me.

I connect with Leah, but also one of the other posters, I find myself feeling overwhelmed. Often I only get to speak to a doctor for two or three minutes, all other communication being relayed to me by nurses, many I’m seeing for the first time, and they can’t answer my questions or address concerns, most promising to contact the doctor and get back to me, sometimes following through, sometimes not.

A compatible system would not be a magic pill, but it could only be a step in the right direction.

Today I drove into work with tears of memories of my mom in which will be 2 years she has been gone. Then I stumbled on this article at work while getting online. I understand some of what you wrote about. I realized early on with my mom’s doctor visits and many hospital visits I would have to be her advocate. Although my mom was pretty good about voicing how she felt… it was always a feat to make sure medical people were following through. What the medical people didn’t know was I was losing confidence in our medical system and them. I have to admit I came across medical people who made effort to call me back and try to remain consistent with my mom’s care. I did try to give the medical people the benefit of the doubt. It wasn’t in my heart to be a hard nose advocate and not even in my personality but I knew it was what I needed to do. As for medical records, my sister and I would learn of knew things we were not informed of or had been told in passing in which we had no idea the seriousness. In some ways, I felt I failed her as her care became overwhelming. I had to learn to do my best and trust God. I can go on but I understand some of what was said in your article and thank you for putting it out there.

As a patient who has recently moved from public care to the Veterans Administration system and have witnessed this first hand. My mental health has suffered and I have ended up in BOTH the VA AND Private emergency rooms. I 5hink I am a smarter than average man and I still had a medication reaction that resulted in a my passing out.

The VA system dispensed both drugs and while I get 2 or more pages of information with each drug the “system” allowed both drugs to pass into my hands without even a verbal warning.

Good Gawd, healthcare in the USA is a nightmare.

I was almost killed once in hospital due to a large dose of a med I’m allergic to and which was noted in my medical records, clearly, at the time.

Just one example. Many others have endured worse, when there’s absolutely no acceptable reason or excuse for it, discounting greed and a poor healthcare system which has run amok, over the past couple of decades.

And it isn’t just healthcare. Look at almost any industry in our Nation and you will find that it’s all gone crazy, lacking any honor, integrity, accountability and beyond caring that it lacks these essential traits.

Sick , from youngest to oldest, are simply fodder to fuel the machine. The machine that runs America. The almighty dollar. Everything else be damned. It’s absurd and it’s tragic, but it’s also here to stay, I believe. Insurance companies do not care one whet when an insured alerts the insurer to the fact that they were billed for services which they never received and further, can prove it! Why? Because it all boils down to a lack of regulation and sweet deals wherein insurers are not about to object to a charge, legit or not. Never mind the lack of legislation to address most of these easily addressable issues which lead to preventable pain, suffering, permanent injury and death. It’s money, people and that’s all it’s ever going to be.

I mean, who wants to see a doctor or nurse with whom they cannot communicate, because that professional does not have reasonable command of the English language. THAT alone, can be a contributor to misunderstanding and resulting serious medical mistakes. What kind of person who considers themselves a NURSE, fails to review a patients allergy list, before administering a potentially lethal drug, due to an allergy to it??? And where was the doc’s head at the time he/she prescribed the medication? Amazing!

Doctors often can be jerks. They do not like to be questioned about much of anything and have no qualms about showing their displeasure when they are. Have we not seen so many examples recounted here. where if the patient, or his/her advocate/caretaker had not spoken up, consequences could have been deadly and in some cases, actually were?

Yes, humans are fallable, but there’s no excuse for dereliction of duties. In failing to read what is before you and taking precautions accordingly. Behaving as if you actually know what your responsibilities ARE! Concerning life and death, these healthcare people should be held to a higher standard and there was a time when they were. Today, it’s a hide the evidence scenario, pass the buck and business as usual. It’s not only disturbing, it’s criminal when so many can create so much harm, when their chosen field demands anything BUT causing harm. And get away with it, day after day. AND be supported by adjunct industires while they often do their worst. Money is all. Peoples’ health and lives are merely a cog in the wheel of greed.

Medicare is such a shambles, it’s indescribable. Medicaid is even worst if a level of worse is possible! What are people supposed to do? Not much we can do in reality. When we’re mere fodder for the machine, our options are sorely limited.

Be diligent and be firm as an advocate for a friend or loved one in hospital or any other medical care setting. Don’t be put off by rude attitudes. Don’t be told NO, when you absolutely KNOW you’re right to be questioning/discussing or even demanding. Personnel are being paid for a SERVICE and you have every right to demand that service be diligent, responsible and every right to be heard. THAT will definitely end up in the medical record, (LOL) but don’t let it concern you, because when it comes to your own or your loved ones care, it truly is up to YOU these days. More so than ever before. Make notes of with whom you spoke and when. Yes, take names! If it protects someone you care about, it’s an essential to do. If someone is negligently harmed, those notes can be everything in litigation, after the fact. However, the idea is to avoid litigation and get your loved one or yourself home, in one piece and well again and thriving. Write to your Congressperson and Senators. Call them. Go visit them. Promote reform.

At any and every opportunity, participate in lobbying Congress and the Senate to enact meaningful legislation to change the corruption and waste within our medical system, top to bottom, including health insurers. And to hold medical personnel accountable for negligence, laziness, poor training or whatever the case may be, in their harming anyone in their care We MUST have a system in place to protect us all and to remove from the healthcare system, any person, entity or group, which doesn’t follow mandated/legislated protocols. Only then can we enter a hospital or other care facility with the expectation of receiving adequate care, minus the warranted fears we often hold today, when undergoing medical care. Our medical records should ABSOLUTELY be available from any facility in the USA, to any other facility in the USA. Anytime. And most particularly, available to us, free of charge, to have in our possession should we travel.

Yes, there are some good docs out there and there are some good nurses out there as well. However, they are part of a dysfunctional, fractured system which hurts us all, financially, physically, emotionally and spiritually. It’s very difficult to “trust medical personnel to know what they’re doing” and that is a shame upon our society as a whole.

We’re all in this together. No one may assume they’re safe in a healthcare system that values itself and it’s profits more than it values the lives of those in its care. Broken is broken and fixed is fixed. May we one day all benefit in the knowledgel that our healthcare system has realized the latter!

Medical information is not kept confidential. My wife’s pregnancy news just about beat her home and she lived 40 miles away from the doctor’s office. NO One- knew, but that office, her and I. I can imagine the many gawking eyes when all records are instantly available from one source. Another first hand story, kids told by nurse, who to avoid intimate contact with, due to a V disease.

One floor battle-axe nurse threaten to rip up a doctor’s order because I wanted to see verification of product dye, before it was administered. (a doctor happened to walk by about then)

This stuff happens all the time in unfortunate work areas and work pools- it frustrating for those that are bright dedicated committed caregivers.

A moral test qualification should be first prerequisite to determine if professional will be honest, transparent, committed to best outcome even when bean counters and bosses are saying… just get’em gone, or insurance won’t pay that.

Record flow- it is not hard to copy and send with patient, or to new provider. Incompetence and/or apathy should be called for what it is. If a professionally trained facility cannot make available, or clinician cannot read and follow chart orders, it is inexcusable and unacceptable- should the training school be liable for graduating this person, or the licensing agency? It is simple, where the ball was dropped is where the liability lands. Honest mistakes happen, but, same’ol allowed selective-stupidity is inexcusable. It is a problem because it is allowed to be.

Also, just sign this patient privacy form, it protects your privacy, they say- read the thing carefully, because you just waved your constitutional guarantee of right to be free from unlawful search, if some agencies were to be so inclined to request records. “I have nothing to hide”, has nothing to do with your right to privacy, or the millions who have fallen to protect, what is relinquished by signature.

Centralization of medical records, will be inadequate- if the same people, and moral ineptness are in charge.

The AMA could have fixed this long ago by promoting penalty sufficient medical self-policing:. They seem to be more concerned with pharmaceutical enrichment through research.

This is a horrible, sad, all to common story. I am a retire RN, one who worked with both paper and electronic records. I do think it is possibly the best solution to empower and encourage and require people to have their own records. My father-in-law had been under VA care for 40 years after a brain abscess resulting from a fall off a truck a few days after D-Day. When he had several admissions in a short time, I saw his paper records—all 6 inches of them. My mother-in-law and I created a summary of his medical history to carry in our wallets for admissions, with dates and brief info about his major medical events. We did not include meds, as they changed often, but she kept a current list. It was very helpful the next times we were in the ER.

On another note, I understand the Japanese have medical books that the parents (mothers) take to each appointment. Sounds good to me, but the peds office I worked in was always trying to find immunization records for families who did not keep even that record. Unfortunately, some of those were stored in a barn across town, by the prior doctor who owned the practice.

Empower patients by Tokenizing PHI/PII (just like credit cards) using digital wallets.

Invoke full recourse (criminal and civil) for individuals involved in PHI/PII breaches. incarcerate or execute are on the table. Too bad for the Social Security Administration, and the Average Municipal Police Department performing background checks. A better mousetrap WILL be built.

1) EXPAND MEDICARE 2) CREaTE UNIVERSAL TRANSITION PROTOCOL IN PLAIN LANGUAGE

Stop telling nurses and doctors how long to be in a room or double the time. Proprietary systems do not work with each other.

I work with elders in the apt setting and the next step unless you are rich is a skn. We need more help in the home. Doctors must be able to listen and have time to read and nurses have excellent training. AN RN is usually a manager- not doing enough direct care.

When we decide to create a system that cares for people instead of systems that compete for the dollar on top of persons who can least defend themselves- we will save a lot of money. My family of origin was turmoiled by catastrophic heath problems and then an early death of the other parent. I have seen it all. Older people in general need to eat great meals with other people- give France a call- they at least know how to feed children. All the services are severely disjointed. Nobody has played the game well enough in this country to have what they need in illness or old age without help from others.

A colleague recently stated at a conference that EHR is now where word processing was in the 1980s.

But I do believe it is getting better….

p.s. I resonate and admire all the comments others have made — thank you:

* alexander galvin;

* eugenia;

* everybody.

<3 this discussion, and sharing of the situation, multiple necessary facets to perceive.

Fern, which episode of the podcast?

“But what choice do we have?”

.

Solution:

Live in small communities of < 250 persons.

Everybody KNOWS everybody.

Village doctors understand their community's history.

Hyper-mobility*, colonialism, and industrialization… supposedly create efficiency.

Certainly they solve many problems (e.g. vaccines for e.g. smallpox).

They also create many problems.

* (as a daily/yearly practice)

We (tribal mammals) have evolved so for millions of years.

Our records of human historical texts only go back ~10,000 (ten thousand) years.

Our species, homo sapiens sapiens, maybe evolved ~100,000 to ~300,000 (one to three hundred thousand) years ago.

All humans started between ~1,000,000 and ~4,000,000 (one to four million) years ago.

Our "modern history" is literally less than one percent (< 1%) of all of human existence…

… and even less of all social-tribe mammals.

Any surprise that we're poorly adapted, poorly evolved, for this type of socio-structural environment?

This article captured my attention because I saw the need also this past year for our health care system to have a site where any licensed doctor or nurse, hospital or other medical facility could access a patients record to find out any and all information in one place for that person. I believe that it would literally save lives and stop a lot of wasted time and procedures. Most of all it would help to see what pharmaceutical drugs were being prescribed to a patient by a specialist other than the primary care doctor, who doesn’t seem to have a clue as to who else or what else you’ve been exposed to since your last visit to him or her. Leah, in this article, was a smart and caring woman to take notes to try and keep up with the info on what her husband was being given. It’s very difficult though to keep track of it all. I hope and pray that our health care system will cut through all the red tape and make it mandatory that all the different hospital systems will have to go outside of their systems and enter the info that might save a persons life at another facility other than their own.

The limit on how quickly people can read and abstract critical information is being exceeded by these systems. It is, let’s say, “Pretty Big Data,” and it is hard to transmit because there is so much of it. Moreover, the thrust is for more written information, and not less of it. Every time a new system is designed for storing this kind information, every time a so-called “improvement,” is made in the data requirements, it inevitably extends the range of information to be provided. People can’t absorb it. Sometimes it’s bizarre. I recently underwent treatment at a large local hospital. Got an X-Ray, a CAT scan, another Cat Scan, a Biopsy (with a CAT scan), a PET Scan, a breath measurement, and on and on and . . . get this, in the process filled out a preliminary set of 8 pages concerning my health, need for an interpreter, etc., 9 times, all completely identical, identical information and check marks. If I’d been smart I would have Xeroxed it the first time and made 9 copies.

This dilemma calls for data entry, storage, bandwidth and clutters up any system. The signal to noise ratio is wrong. This amount of information cannot be transmitted among people in this way. We’ve known about information theory for 60 years. Humans cannot read faster than they read. And you cannot give them piles of information muddied by piles of reflection and misinformation and expect them to learn it in short order. It might be possible to have computers collate and analyze it for us, but such systems do not yet really exist.

My mother had COPD (emphysema) and congestive heart failure. The last 6 weeks of her life were spent in medical care: first in ICU for tachycardia for nine days, then to telemetry. After two days in telemetry they sent her to rehab. I repeat two days after nine days being catheterized and never getting out of bed, they sent her to rehab at the nursing facility. We argued with the hospital she wasn’t ready but they said it would cost us a lot of money to keep her there. In rehab she was to have two nurses assisting her to the bathroom. One day one nurse said to the other, “let’s see what she can do” and just watched her struggle without assisting her. She walked 100 feet the first day, and was not able to repeat that therapy. Too many errors to go into details, but she came to rehab the Friday before Labor Day that year. Sunday night, the night before labor day, there was NO ONE available to help her to the bathroom. There were only two people on the whole floor of many beds (60?). We asked one of the aides to come and she said she would come as quickly as possible but she had been on the floor for 16 hours without a break. Multiple support staff had “called in”. The next day they let her rest. I gave her a kiss goodbye to go back home 2 1/2 hours away, another one of my sisters would be in shortly. That sister came in saw my mother was very weak, asked them to read her oxygen. It was 72 and she was in tachycardia again. The head nurse said “oh she has COPD? she has congestive heart failure?” She had never read her chart at all. Back in ICU again, then again to telemetry for now many days. She was given a pacemaker because the meds would not regulate her heart rhythm. After that, they sent her not to rehab but to transition care. The oxygen tech was so pleased when she got her oxygen up to 98. Her type of COPD required it be kept no higher than 94 but it took multiple days of my mother hallucinating she was living back in Civil War times and knew Lincoln and another sister arguing before the tech finally realized my arguing sister knew what she was talking about. The hospitalist at rehab was the best, he went over every little bit with us in clear terms. She started to improve and actually called me to say she decided she wanted to recover and go home until the day a nurse left the room while mom was on the side of the bed nebulizing. She had a fall risk bracelet on and was not supposed to be left alone. So she fell off the bed and was so mad she broke a dish and cut her hand open. After that the will was gone. After a few days all 6 of us siblings agreed to her wishes to go home and die. She went off all meds and we arranged for hospice care to come at home. The night before she was to go home, my older brother and sister and I were in the room. They kindly let us stay. One of the night nurses apologized because “we had him” – meaning the other night nurse. At midnight, my mother looked me full in the face, sitting on the side of the bed while my brother supported her. Well, Ann, isn’t it time to take me home? Oh, Mom, just have a nice night’s rest and we’ll take you in the morning, I said. I dozed off on the spare bed. The night nurse came in and asked my brother if it was ok to give her morphine, and said it might repress her breathing. My brother nodded, but he was not the proxy. When I woke up she was in a coma. Never made it home. She died at 3pm. So so many failings of the health care “industry”, despite 6 of us watching over her in shifts for the whole time.

No choice? You have a choice. You’re the highest paid medical professionals in the world, with a nation that spends more on health care than any other. You certainly can improve this. You choose not to, because leaving it the way it is results in more money lining more pockets and more people having a sense of pathetic power by keeping a patient’s records from them, instead of letting them have their records as they do in India, as another poster stated below. There ARE choices. There ARE ways to improve. YOU choose NOT TO. And it doesn’t seem to matter to you who dies in the process.

I like the suggestion of James Auran, MD. Even better, through legislation (with teeth) REQUIRE that EHR systems providers and health care providers share information via the HL7 FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) standard. The legislation should require that all of the patient’s healthcare information be provided to the patient at no cost to the patient, provided that the patient provides the necessary storage media (USB, cloud services, etc) and/or specify a trusted repository (such as that provided by Epic or someday perhaps Amazon, Alphabet, or Bank of America).

The whole selling point for EHR was easy access to all medical records by all healthcare providers. Now it serves no real purpose because each system is so proprietary. Many very experienced healthcare providers are penalized by private and government insurance plans because they do not use EHR. Many practioners have chosen early retirement because of this. When my late husband was in intensive care for 7 months, I watched a parade of various nurses and doctors visit my unconscious husband without ever consulting previous records. As an optometrist, I can vouch for how much easier it is to flip between pages of previous visits to compare than using EHR. Electronic Health Records limit the communication a healthcare provider can convey in a record. It is point and click, not personal in any way. If you need to make notes or document something out of the ordinary, it is difficult. Our healthcare system is very flawed; EHR compounds the problem rather than fix it.

God help us all. In this time of new medical marvels occuring almost daily, it is all for naught. Our chances of receiving and continuing to receive the proper treatments are compromised by poor communication…one person’s inability to communicate fully and properly with another regarding medical records and treatments. No wonder so many people die in hospitals and care facilities.

At age 75 (this year), I had my first (to my knowledge) and very prolonged A-fib attack and was in ER for over 11 hours. The afib was not responding to their meds meant to calm the heart. My husband, who has a medical background, had at my urging stepped out to get something to eat.

During that time, they decided to try a medication WHICH IS CLEARLY LISTED AMONG MY ALLERGY MEDS, and he was not there to tell them no.

Their system is all computerized and up to date. They SIMPLY DID NOT READ the available list of drugs to which I am allergic.

It did finally lower my heart rate, & I was put in a cardiac care unit, finally fell asleep, then was awakened by a furor of attendants applying paddles because my heart had stopped (“paused,” in their vernacular).

It’s so important to have full medical records, especially when traveling, but what can a patient do when the staff HAS ALL THE ALLERGIES LISTED, AND SIMPLY DOESN’T READ THEM?

Nurses don’t care. One nurse I met was creepy, more interested in financial rewards than patients.

The failure of the current EHR is by design. They announced how the data was supposed to improve healthcare, years ago. They were peddling expensive data systems, while at the same time limiting the collection of data to what they considered useful, mostly marketing information.

The healthcare industry mane no attempts to create a meaningful medical record, with the help of other industries, like pharma, who tend to profit better in the dark. Pharma did not want physicians, or anyone tracking pharma deaths in real time. The current stem was truncated by so many different interests. Physician did not want to leave paper trails, since it could potentially lead to liability. At the same time the intrusive collection of data, had people thinking that it was already there. Medicare as the largest insurer should have demanded better data, and medical records, unfortunately industry groups and their lobbyists, claimed that collecting the data was “government overreach.”

Industry bean counters, lawyers and profiteers know exactly how this missing and confusing EHR can be used for financial gain, and to obscure mistakes, and unnecessary procedures. They koew how to exploit this for profit.

The model now is that any time an under-insured person accesses healthcare, if their insurance does not pay enough, for what they need, can be turned away or postponed. This also applies to minorities, non gender binary people, and woman. Each time they see a physician at the same clinic, the clock starts. They start with a new slate every time. This way healthcare can be denied, and given to someone they deem more worthy, or billable.

This missing medial record has been particularly helpful for physician that refuse to acknowledge surgical mistakes, or unhelpful previous health interventions. If they don’t know about the previous record it is as if it never happened. Physicians are also subject to Gag Orders, so if a patient had an adverse event previously, it will not be discussed or acknowledged. No one keep track of the trauma they cause intentionally or the number of deaths.

The profit driven model did not see clear medical records as beneficial, while at the same time they ‘educated’ patients and shareholders that there was a data revolution. They were Gas Lighting us all. The only data they collected was the most minimal necessary for billing, they did not want anyone to be able to piece together their records. It could lead to criticism and liability, and for non profit providers, it could cut into their “excess” funds. There is even something claiming that patients have “Rights” to their medical records, but that is a lie, who would enforce that?

These Data Gaps are all by design, meant to obscure the actual records, and make it difficult to track mistakes, over charges, and duplicate procedures. Physicians won’t even refer to their intake questionnaire, filling hem out is busy work for patients, and gives them the false impression, there is something for the physician to refer to.

The Market Driven healthcare system has gotten too unwieldy and corrupt to even pretend the records mean anything. The industry clearly obstructed any attempt to standardize or connect these records. With no record they can provide whatever care they deem profitable, while picking patients with better reimbursement rates. The Data Gaps are even in the same system that generate the records. To avoid liability or accountability, they remove inconvenient records. This is pretty typical of post surgical adverse events. They will even remove surgical notes if there was anything that could lead to liability.

We are in Post Fact America, where corporate interests supersede our health. The system is flawed by design. American Healthcare is the most expensive and has worse outcomes, than any other developed nation. There is little meaningful regulation anymore, and nothing gets done without the profiteers input. They marketed expensive data systems to these healthcare providers, yet none allowed them to collect meaningful EHRs. Hospitals even advertised that they were going electronic, a meaningless public relations or advertising claim. Further proof is to just take a look at what Medicare is allowed to collect. Even the ACA had a provision for updating the records and creating an EHR , yet the industry refused to do it. They depend on keeping us all in the dark, for profitability.

I’m the caregiver for my husband, who is in the late, last stage of Parkinson’s. He broke his hip last fall and was flown to San Francisco from where we live, 300 miles away.

I found myself wondering if the rehab he’d been sent to south of S.F. was one of the ones you mention here. Despite clear instructions from the doctor, they mismanaged his Parkinson’s medications badly in the first two weeks he was there, despite my pleading with them. I finally had to call in the county ombudsman’s office to intervene — it was the only way I could get help. They were leaving him violently shaking and thrashing in bed while withholding his Parkinson’s medications when he needed them. Then they started overdosing him on his meds… He was finally sent home with a stage 4 pressure sore and missing his wedding ring.

The ombudsman’s office assured me that, compared to most of the other facilities around there, this was a good one. If that’s good, I dread to think what is considered bad.

My husband is now home in hospice care. It’s a nightmare.

I laughed out loud when I read this part:

“The American health care system is dynamic by design. Patients move from one hospital to another; from a hospital to a rehab facility; from the wards to the intensive care unit (ICU); from the hospital to a primary care setting. These transfers are inevitable, as a person’s health either improves or declines, or if that person simply desires a second opinion. In non-emergency situations, it’s somewhat of a medical free market. Patients have every right to take advantage of it.”

That’s a very precious interpretation of our health care system.

The reality? Patients move around because insurance controls the doctors we see. Sometimes the insurance drops doctors. Sometimes they give up jumping through hoops and stop working with our insurance companies. Sometimes we change jobs, and our new insurance doesn’t cover our old, trusted doctors. And sometimes work changes insurance companies, and again, we lose access to our old doctors.

If we keep going to a trusted doctor that in-network $40 visit turns into a $180 out-of-network visit.

Health insurance also questions every visit, every need, every problem. If it’s not big enough, or painful enough, or serious enough, they deny coverage. If a condition gets “good enough”, they refuse further treatments until the patient does poorly again. With my chronic health conditions (going on 9 years of treatment) I never get better because insurance refuses to pay once I’m no longer in severe pain or have some level of functionality.

Getting the person who makes the decision to deny my visits to talk to ME, the patient, the person being slowly killed by bureaucracy and greed is impossible. Literally impossible. It’s not allowed. My doctors have to jump through hoops. I have to call again and again, hoping to get a representative who has empathy and will tell me what I need to do. Sometimes the problem is literally a code – a different code will allow something to be approved. Sometimes the problem is that I reported my daily pain is 7 out of 10 – for further treatment, it has to be 8 or higher. Sometimes insurance says that they won’t approve treatment because there is no proof that it will help – how do I prove if something will help me or not if I can’t try it and see?

In short, our health care system is profoundly broken on multiple levels. It kills untold numbers of people every, single day. It’s not a medical free market that patients can take advantage of. It’s a medical nightmare that abuses and drains people when they’re already ill.

The way this patient was abused by the system doesn’t surprise me. The only that does is the assumption that any part of health care does anything good for the patients.

26 years ago, I brought home my twins. They had been born at 26 weeks and were hospitalized for 12 weeks. They came home on apnea monitors with instructions from the nurses at the unit, but a lot of information was missing. I am an RN with 2 other children, so I just guessed at what I needed to do, acting on what I knew they had been doing at the hospital. I quickly realized that they were having trouble keeping their temperatures at a normal level. I moved them into the living room by our wood stove. I slept on the couch, when I could sleep. By the second day home, one of the babies began having apnea issues. I called the Dr. office to be told that they had apnea monitors because the Dr. thought they might have apnea, so I should not be worried. I insisted that I bring them in to be examined. I got a friend to go with me, but had to switch to riding instead of driving when the baby stopped breathing. I got her to breath again very quickly, but she was breathing too slow. When I got her out of the car, she started crying and breathing normally. I insisted that she be readmitted. The Dr. thought she did not need to be but agreed to some blood work that showed extreme anemia, so she was admitted for a blood transfusion which she had needed 2 other times. By the time I got home, the hospital called and said she had a respiratory arrest at the hospital which was severe. She was stable at present but would need to stay awhile. She stayed for 2 more weeks. When she was discharged, the Dr. came in and said to follow the directions he had sent home the first time. Well, he had written 2 pages of information on the babies care that I never got. One thing on the list was to return them to the hospital if their body temperatures were not stable. I only knew there was that problem because of my background as a nurse. I did not know that the Dr wanted me to take their temps 4 times a day. It also outlined what to do for apnea episodes and when to call the Dr. A child without a mother as a nurse probably would have died, all for the lack of 2 pages of Dr.s orders.

I create medical blue books for myself, family, friends and colleagues..It is,an invaluable time line…of medical reports, discs, research ,referrals. You can hear my story on futuretech podcasts, how to be medically proactive,being informed , being proactive and taking charge of your health.

The doctors who have seen this book were glad that a history and timelines were created…it saved them time and offered great insight for the patients future treatment.

If Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, can keep track of all your purchase information and accounting financial information, logic says one day they will organize all your health data in one place on encrypted servers that will be easily drilled down to details about your health in a timeline fashion.

I often tell patients: every doctor/hospital has their own electronic medical record (EMR) system and they can’t communicate with each other. It is all because of greed. Every EMR provider wants to protect their turf and won’t allow information sharing. It would be as if each bank issued their own currency and you couldn’t exchange one banks’ currency at another bank. If this were the case, the financial system would quickly collapse. But here we are in medicine with the same situation, only instead of the system falling apart, the patients suffer. All it will take is the stroke of a pen by lawmakers: force them to allow information to be shared across all systems.

Several years ago our family doctor in Texas died suddenly without a directive for control of her medical records. We tried to get our records from the doctor released but could not. How common was this? Any hope on recovering them?

I find the fact that the bar is so low for when people are transferred or discharged also causes issues. Because of some bureaucratic rule made by accountants at Medicare and what they are “willing to pay for” or for how long. In order to “standardize” billing and rules it loses all common sense. Like somehow 10 steps means you are good to go home as has happened when my mother was having issues, that turned out to be a bad reaction to a medicine that ended up with her back in the hospital 4 more times over as many weeks. Or as my diabetic mother was in a SNF this past week, just across the bay from this doctor, and ending up with a 501 blood sugar because of no good reason. Where she made the comment that she feels worse than when she came in because they wouldn’t give her insulin timely. But I can’t be there 24/7, I have a full-time job and 2 kids to take care of. That’s what I’m hoping the doctors and nurses will take care of. And this is with the same hospital and skilled nursing facility. It’s not cookie cutter but that’s what they want it to be. So I’ve experienced these gaps, but it’s more than just the records. It also has to be more than the bottom line.

I’ve also agreed on other occasions to discharge my mother to home so that she’s not subjected to exposure to all the bugs that go around hospitals. I get the risks, but sometimes I feel, if they could stay for a day or 2 more and just get over a few additional hurdles, they’re recovery at home goes better and lasts longer too.

Empower the patient, like in India, some doctors let patients keep their records. When they visit the hospital they have a whole stack of medical notes with them. It’s time to digitalise into USB device or handphone icloud record. With international travelling,your medical records need to be with you always if you want the best care.