A Math Lesson From Hitler’s Germany

In 1934, David Hilbert, by then a grand old man of German mathematics, was dining with Bernhard Rust, the Nazi minister of education. Rust asked, “How is mathematics at Göttingen, now that it is free from the Jewish influence?” Hilbert replied, “There is no mathematics in Göttingen anymore.”

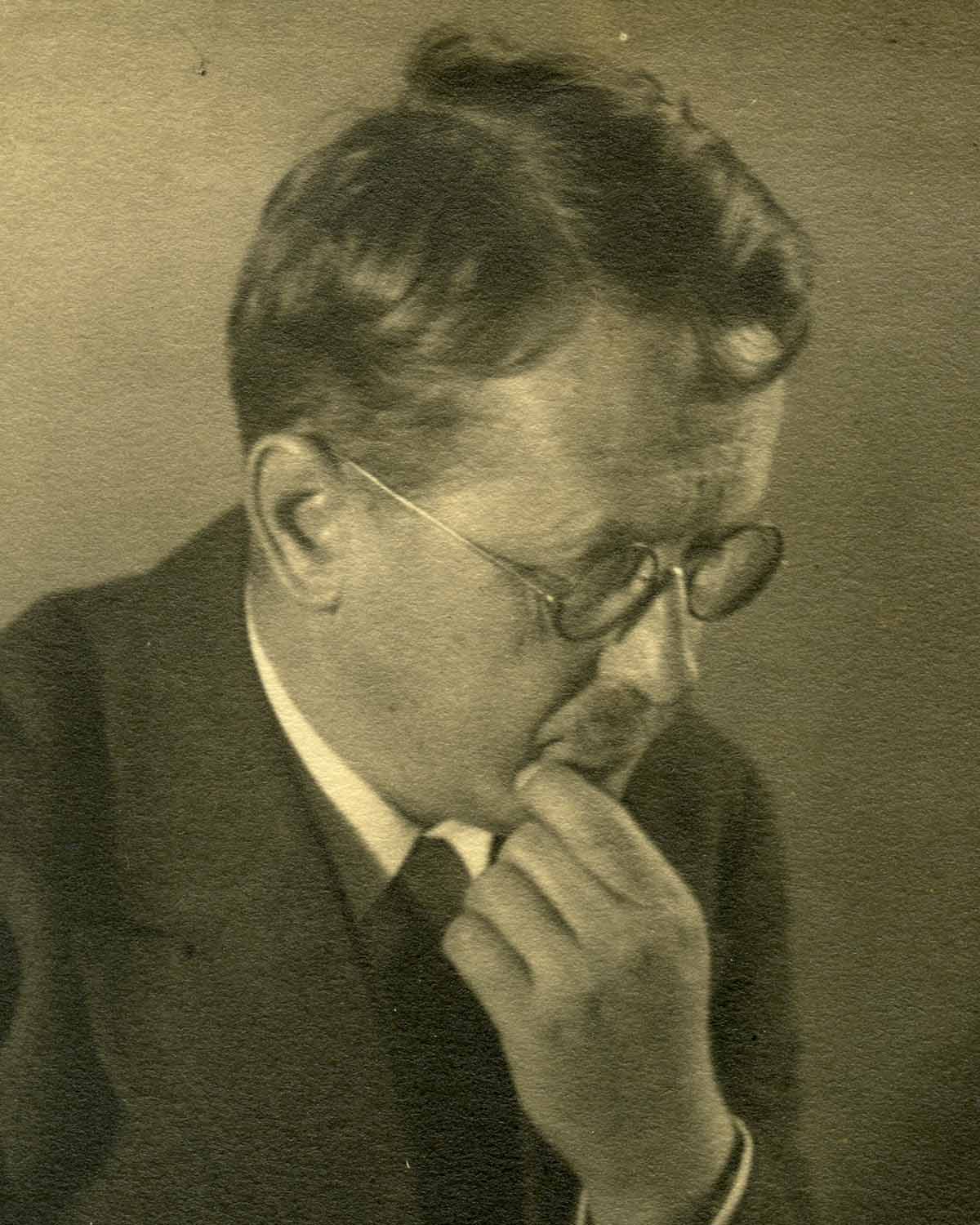

“There is no mathematics in Göttingen anymore”: the German math giant David Hilbert.

Visual: Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Or so the story goes. It is folklore at this point, a story mathematicians tell one another over coffee while exchanging knowing looks. The details vary in different retellings, but every version has Hilbert speaking this truth to power: Nazis destroyed mathematics at the University of Göttingen. “It’s one of the most well-known stories in the history of science,” says Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, a math historian at the University of Agder in Norway. “Göttingen was so dominant in mathematics internationally.”

In 1933, that dominance came crashing down. On April 7, two months after Hitler became chancellor, Germany passed a law making it illegal for Jews — or rather those considered Jewish by the Nazis — and Communists to hold civil service jobs, with a few exceptions including for people who had served Germany in World War I. That immediately forced several Göttingen mathematicians from their jobs. The crisis snowballed, and over the course of the year, a total of 18 left or were driven out.

By the time of Hilbert’s legendary dinner with Rust, Germany had lost its status as the world’s foremost country for mathematical research. America took its place — and today, though globalization has spread the wealth, the U.S. has retained its eminence. From Princeton and Columbia to Berkeley and Stanford, it’s hard to find a great math department in the United States that was not shaped in part by European mathematicians who came to or stayed in the U.S. because of the Nazis.

As a new administration with a pronounced anti-science bent takes power in the United States, some scholars are recalling what happened at Göttingen as a cautionary tale. Donald Trump is not Hitler, of course, and “history doesn’t repeat,” as Siegmund-Schultze puts it. Still, he quickly adds, “One also knows from pain that mankind doesn’t really learn from history. Otherwise we wouldn’t do all the same foolish things all the time.”

American democracy is far stronger and longer-lived than was Germany’s between the wars. But we should take the similarities seriously. “I think what you see in both cases is this disaffection of the lower middle class,” says Julia Ault, an expert on German history at the University of Utah. “Part of their status rests on being better than someone else.” Lower-middle-class Germans in 1930 might have felt a loss of status if they perceived Jews to be advancing more quickly than they were. Ault sees a parallel to what some white people in rural America feel: They perceive immigrants as coming in and rising more quickly than they are.

Rather than a drastic Nazi-style crackdown on free speech, what is alarming many scholars today is the idea of a post-truth world, in which evidence doesn’t matter if a story reinforces your beliefs.

“In some sense every scholar is at risk,” says Robbert Dijkgraaf, the current director of the Institute for Advanced Study, which attracted many of the scientists and mathematicians who fled Göttingen and other German universities in the 1930s. “It’s not so much that people are persecuted because of their beliefs, but there is a certain trend where careful reasoning, the search for truth, all the delicacies of having a balanced point of view, acting on facts, being honest about what you do and don’t know, your uncertainty, all these values we have in science and scholarship are at risk.”

The dismissal of experts and the appeals to populism are dangerous, says Ault. “It’s going to be hugely devastating to the EPA, to climate science.” Trump, who has called climate change a Chinese hoax, has asked for the names of scientists who study global warming. His transition team backpedaled on the request, but it was unsettling for employees of the Department of Energy. More recently, it was reported that his administration issued a temporary ban on external communication from the EPA and blocked the agency from awarding new grants or contracts. “It’s going to take most of our lifetimes to redo what’s going to get undone in the next four years,” Ault says. And for that reason, the political cataclysm that upended the mathematical world in the 1930s is no mere historical curiosity.

Carl Friedrich Gauss, one of the greatest mathematicians of all time, helped establish Göttingen’s prominence in the early to mid-19th century. The tradition was continued by a legion of people whose names are sprinkled throughout calculus and physics textbooks today: Riemann, Dirichlet, Schwarz, Klein, Minkowski, Landau, Noether, and Hilbert, who had to a large extent set the mathematical research agenda of the 20th century with his 1900 list of 23 unsolved problems he thought mathematicians should devote themselves to in the new century. Richard Courant, who was part of the 1933 flood of mathematicians leaving Göttingen and for whom a New York University institute of mathematical sciences is now named, helped secure funding from the Rockefeller Foundation for a new building to house the mathematics institute at Göttingen. It opened in 1929, and for the next few years, mathematics in Göttingen continued to thrive.

Providentially, the institution that would in many ways take Göttingen’s place — as a home not just for world-class mathematicians but for German Jewish ones — was being born at just that moment, in Princeton, New Jersey.

The Institute for Advanced Study, known to mathematicians and scientists simply as “the institute,” was founded in 1930 by the Bamberger family, who had sold their department store to Macy’s shortly before the stock market crash in 1929 and had thus managed to prosper through the Great Depression. At the time, many American institutions of higher education were anti-Semitic, and the Bambergers’ initial vision was to create a medical school that did not discriminate against Jews. Instead, Abraham Flexner, who had studied and written about medical and higher education, convinced them that an institute dedicated to basic research in mathematics and science was more important. He ended up joining them as a founder.

The institute opened in 1933 and was housed in Princeton University’s Fine Hall, home of its mathematics department, until the institute’s own facilities opened in 1939. (This has led to decades of confusion about the institute’s relationship with Princeton. They are in the same town, but they have no formal affiliation.) The timing could not have been better for the German Jews whose jobs at home had been abolished. Flexner and the trustees decided, with the help of the Rockefeller Foundation, to create positions for exiled researchers at the institute.

It wasn’t an easy sell. American anti-Semitism was not the only issue; unemployment was high, and some believed that “every foreign scholar imported means an American out of a job,” as the MIT mathematics professor Norbert Wiener described it. He feared that “any appointment for more than a year would cause a feeling of resentment that would wreck our hopes of doing anything whatsoever.” Dijkgraaf, the IAS’s current director, says the institute had to walk a fine line. “All these efforts had to be done in a very subtle way,” he says. For one, each grant was fairly modest. But by getting a position at the institute, even a temporary one, a researcher “could at least get a visa and would have a foothold” as they worked to find jobs elsewhere in the U.S., says Dijkgraaf. “There was this joke that the institute was a little bit like an Ellis Island for these scholars at risk.”

In a 1939 report to the Institute for Advanced Study trustees, Flexner wrote, “Fifty years from now the historian looking backward will, if we act with courage and imagination, report that during our time the center of gravity in scholarship moved across the Atlantic to the United States.” And he was right. “In the end America profited hugely,” says Siegmund-Schultze, who adds that “many of these developments would have happened anyway even without the Nazis.” After all, America had more resources, the population was growing, and the nation was starting to replace private financing for the fundamental sciences with public financing — a large part of the reason the U.S. was able to retain its mathematical and scientific dominance after World War II. Nevertheless, America’s willingness to take in scholars fleeing the Nazis provided a boost to its rising scientific establishment and caused the balance of power to shift almost overnight.

“We now think of it as a given that the United States is a center of research and scholarship,” Dijkgraaf says. “It wasn’t at all in the 1930s. It was this brave act and this generosity that allowed this to happen.”

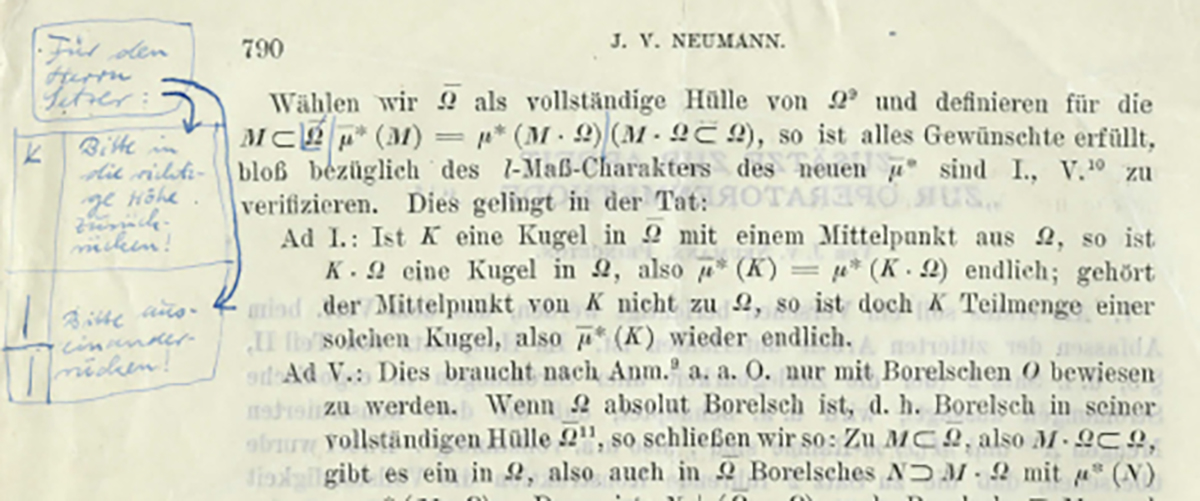

Albert Einstein is the most famous émigré scientist who ended up at the institute as a result of that generosity. Other luminaries included John von Neumann, a Hungarian mathematician, computer scientist, and physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project; Hermann Weyl, who had been Hilbert’s successor at Göttingen; and Kurt Gödel, who changed the way mathematicians think about certainty.

As that star-studded list suggests, taking in these refugees was not simply an act of generosity. Oswald Veblen, who had been influential in getting the institute to Princeton in the first place and had become one of the first scholars at the institute, “had a very clear vision that this was a win-win situation,” says Dijkgraaf. “He could help the refugees, but it was also a unique opportunity to strengthen mathematics in the United States.”

Institutions are fragile. They are easier to destroy than build. A few months of Hitler’s policies unraveled two centuries of mathematical progress in Göttingen. That university, and Germany more broadly, never fully recovered. As von Neumann correctly predicted in 1933, “If these boys continue for only two more years (which is unfortunately very probable) they will ruin German science for a generation — at least.”

America benefited hugely from the intellects of displaced mathematicians and scientists 80 years ago. And while America’s scientific institutions are not facing the same sudden existential threat Göttingen did in April 1933, their work and their scholars can still be seriously undercut by anti-science and anti-intellectual policies. It would be a tragic irony if American mathematics and science, which owe much of their status and success to the German prejudices of another era, were brought low by a kindred set of attitudes in this one.

Evelyn Lamb is a writer based in Salt Lake City. She taught mathematics and math history at the college level before leaving academia to pursue writing full time. She was AAAS mass media fellow at Scientific American in 2012 and has written for outlets including Scientific American, Nature News, the Smithsonian Magazine website, and Slate.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

This is happening now in Florida.

https://politicalwire.com/2022/04/17/florida-bans-dozens-of-math-text-books/

It’s confusing

Heidelberg, not Nürnberg. Nürnberg was the town of the party conventions. It was razed to the ground.

It certainly could happen here under Drunpf.

This comment section has been flooded with forceful right-wing anti-science comments which are all similar in tone. It is important to ask how that happened. Do a large number of right-wing ideologues read undark.org? I am skeptical. Perhaps the most likely explanation is a comment campaign directed by a political propaganda organization.

I probably hold what you might find to be anti-science right wing views. I hit upon this site looking for a citation for the Hilbert quote, with which I am quite familiar. No nefarious right wing plot.

My objection is not to “Science”, but government sponsored neo-lysenkoism. I don’t think the Trump administration is so much anti-science as a threat to a lot of people’s rice bowls. And they know it. Scienticity is the first refuge of a second rate mind. I give you Bill Nye. Granted calling Bill Nye second rate is an insult to second raters.

In case you haven’t been paying attention, the real threats to free speech and academic freedom are not coming from what you characterize as the right, but from the bowels of academia itself. Physician, heal thyself.

See “Mathematics at Göttingen under the Nazis” by Saunders Mac Lane, at http://www.ams.org/notices/199510/maclane.pdf

For those who believe Hitler was elected, go check your history. Hitler was appointed, legally, by the elected government in an attempt to keep the nazi’s in check. Hitler used the position to usurp the German govt. As long as the US maintains checks and balances between the branches, no president can become dictator in chief. Although, the actions of the previous office holder laid bare weaknesses in congress by using the power of the executive order to rewrite law setting a dangerous precedent for the future. The horrors of nazi germany only occur when elected officials vote to remove their own power. As long as the US follows the constitution, it is illegal for the congress to legislate away its power. Thank your stars that the US is always in a constant state of disagreement and neither side wants to legislate away its power to an individual otherwise another Hitler could rise.

As far as I’m concerned progress in mathematics is completely unrelated to work in global warming. Math is rigorous and well thought out. Global warming theories are not well thought out or vetted. I am a lowly engineer. We deal with the practical. If someone asked me to measure the temperature of the earth to within 0.1 degree C, I’d say they were crazy. I deal with heat transfer all the time. I know that in order to make a measurement you have to meet the lumped capacity requirement at that point, once you get far enough away that the lumped capacity requirement is no longer met, the temperature is no longer representative. Yet I never hear anyone mention the Biot number, nor ask how many temperature measurements it would take to measure the temperature of the earth. Scientists don’t ask such questions they just go on with their work assuming that their measurements are correct. Then when we don’t believe their results, they accuse us of ignorant, or as this article suggests, Nazis.

That all may be true, but is it relevant? If the measurements exceed the variance of the method, then they are real even if the method isn’t as precise as one would like. Most real world situations cannot be experimentally controlled as well as we scientists would like.

One might also examine what happened at the University of Berlin. A veterinarian, albeit with the correct political credentials, was placed in charge of the facility. He removed quite a number of senior’s level and graduate courses and replaced them with,…advanced veterinarian’s courses. The Nazi’s were antithetical to science and in spite of what the Media never tires of telling us, did not in produce excellence in industrial engineering. What was novel and good was a legacy of the pre-Nazi years.

How did I know, when I saw the name “Hitler”, that it would somehow be associated with Trump?

I despise what the German regime did to my family.

However lets keep science and politic separate.

That same Regime had the most advanced mathematics of the time to produce a sophisticated rocket program.

Left, Right, Creationist, Atheist…all use the same science to design a battery or do Heart Surgery.

The downfall of climate change research is in the hands of the same researchers now crying wolf. If you all had adhered to historical scientific principles and critical peer review of your work the criticism from the market would not be as loud and truthful. You can look down upon us “mere mortals” and tell us we are stupid, except, we see the evidence that the raw data from NOAA and NASA used by most climate researchers has been arbitrarily changed and biased to achieve the desired politically correct outcome. We remember the leaked emails from the climate change academic leaders discussing how they changed the data to achieve political outcomes. We understand the evidence that the climate models used by academia are terrible predictors of future outcomes. And, even with these less than adequate tools, the debate on the amount of climate change caused by humans is still almost inconsequential in future predictions. Yet you Scientist continue to run around screaming the “sky is falling” only to be disproved year after year that your apoplectic predictions never pass. American’s will regain their trust and confidence in science when you SCIENTIST stop pushing a political agenda and begin actually conducting real, substantive and meaningful research that adheres to the stringent academic standards that you profess to support. Until you clean up your house predictions like the ones in this article will just be ignored. And until you clean up your house why do you expect any respect from taxpayers funding your lifestyle.

This comment is actually an example of the misinformation that is prevalent in the American right today. The truth is that there are outstanding scholars all over the world demonstrating the reality of anthropogenic climate change, using independent mutually-verifying methodologies. Their published work is peer reviewed and scholarly.

The idea that climate scientists artificially altered data is a misconception. They performed a correction discrepancies between ocean temps as measured by buoys and those measured by ships. It was recently proven that the correction was accurate: http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-38513740?SThisFB There was no fabrication, but it was good science that has been skewed the other way by those eager to cast doubt.

The campaign of misinformation coming from the anti-science crowd has obvious motives: The giant fossil fuel industry. Hitler’s Germany it is not, but a culture of denial of scientific results for financial and political ideologies it is.

You are so fast to call everyone names in an attempt to stop the discussion or more accurately the intense scrutiny the scientific community is about to undergo. No one is against science – just fake science perpetrated upon society by politically motivated scientist.

If you have the time you might want to read this recent article from the UK Daily Mail: Exposed: How world leaders were duped into investing billions over manipulated global warming data.

Here is the link to help you:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-4192182/World-leaders-duped-manipulated-global-warming-data.html

The fact that this article was even written demonstrates there is “something rotting in Denmark”. Your focus should be on your community and the current practices. Clean up your house and then talk to us.

> “we see the evidence that the raw data from NOAA and NASA used by most climate researchers has been arbitrarily changed”

What specific raw data are you talking about?

What specific “evidence” do you have that says the data was changed?

In what specific way was the data changed?

I wish I could credit the person who first said this, but that piece of my memory never came back from Auschwitz. Anyway, here’s what (s)he said:

The one thing to learn from history is that nobody learns anything from history.

What demonstrates this better than America’s wonderful war on drugs, after the huge success of prohobition?

That was Hegel, approximately “The one thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.”

Comparing a duly elected President of the U.S., no matter what his political leanings, to the Nazis in any way shape or form is the equivalent to shouting fire in a movie theater when there is none. If only the intention of the author was to write about the sad and regretful way this German university lost its scholars, without making bogus assertions about the dangers of a Trump administration, I would have read the article in a much better light.

@Jerry Syder: As others already said, the democracy in the current US is far more stable as it was in Germany in the 30s of the last century. So hopefully it will also survive trump. BUT in 1933 Hitler was also duly elected chancellor of germany.

As I read this article, it wasn’t long before I could tell where the author was going with this, the ” deplorables” to blame all over again. Disgusted, I skip to the comments and I am encouraged. Thoughtful, intelligent comments, taking the author to task and articulating my arguments much better than I am capable. Thank you all.

The violence & denial of Free Speech comes from the Left in the United States, just as it did in Germany in the ’30’s.

“a pronounced anti-science bent” again comes from the Left, telling everyone who disagrees with CAGW to ‘shut-up’.

“UnDark” wouldn’t know the Scientific Method if it came up & bit them in the butt.

An Aryan orthodoxy ruined the math departments in Germany…much like the Luddhite, anti-capitalist, AGW orthodoxy is ruining climate science. Some of the best paleoclimate data resources are the cores from the petroleum industry’s research. It is apparent that AGW proponents are suppressing climate history and important factors such as glaciation cycles, bolide impacts, volcanic eruption s, geologic changes like the formation of Panama’s isthmus or Drake’s Passage, and solar cycles as they focus on CO2 levels. The lower CO2 levels during the Pleistocene were unusual as are today’s levels when compared to most of Earth’s history

When US labs announced the average global temperatures they used to include the uncertainty in the measurement. That important piece of information has been dropped from the press releases of NASA, etc for the past 6 or 7 years. Thus, they can claim that an increase of 0.01 degrees over a previous year makes this the hottest year ever’! The uncertainty is actually on the order of 0.1 of a degree, so the proper claim should be ‘no change from previous years’! This is only one example of the unscientific behavior of climate change advocates that perhaps the new administration can correct.

It’s pretty sad and shameful that the author of this article would take such a horrible chapter in the history of Human-kind and try to make contemporaneous political hay out of it by pushing narratives that are fake news.

Please go back and look at the voting demographic of Hillary vs. Trump voters. She led the votes only in households that have less than $50K in income. Liberals are the ones who want to feel superior somehow by using their various degrees in concentrations like Gender Studies or White Privilege as a cudgel against those of lesser education, but of greater contributions to the economy and society.

Nazis objected to the social station of the Gottingen mathematicians, not to their math. With climate science, no-one objects to the persons carrying it out, only to the quality of it, and to the cost relative to any likely usefulness. Indeed, many observers suggest that climate science is itself an underminer of research quality, through corrupt peer review. Look no further than US liberal arts colleges, if you want to see how academic quality can be destroyed. A better and closer example than Gottingen.

Middle class might have felt that way, new administration with a noted anti science bent. Please get rid of all the bs arguments and just call Trump Hitler. I get sick and tired of hit pieces trying to look like actual science. Trump is the elected president of the United States and with our three branches of government no matter how bad he is it limits his power. This is the first time since the founders that we have a businessman in charge, not a political lawyer. He won, let it go.

I agree. Also, note the slam at the “lower-middle class” about wanting to feel superior to someone (“Part of their status rests on being better than someone else”). In my experience, that simply isn’t true. The people that I know who could be classified as lower-middle class want the same thing almost everyone wants, secure employment, hope for the future, better life for their kids, etc. Why does the left always make it about racism, and why are they always so bigoted against people who simply disagree with them on social policy? My guess is that they simply don’t know many people from across the socio-economic spectrum, but I’m probably being generous. It is more likely projection of their own hatred and bigotry and status that comes from being better than someone else.

Pseudo-religious Climate catastrophism, anti-GMO / anti-vaccine / anti-nucleat hysteria.

There’s plenty of pseudo-science and anti-science left wing ideology, the right had no monopoly on it.

No, Donald Trump isn’t anything like Hitler, but the atmosphere in most contemporary academic communities is incredibly intellectually intolerant. In fact, there are probably more comparisons to be made between a university campus and Nazi Germany than there are between Adolf Hitler and Donald Trump.

Academia is doing tremendous damage to itself with this sort of apoplectic virtue signaling.

If you look carefully into the views of Donald trump and Hitler you would in fact see a lot of similarities as Hitler did say as i quote ” Make Germany great again!” so the fat that Donald trump has taken this Nazi slogan and made it into something that he is recognised for saying is in itself quite disgusting. Donald trump is a racist and he is not very subtle in the way that he shows this also another horrible trait that Hitler also shares with Hitler it is not a secret that people think that Donald trump will turn into a dictator as he is appealing to The working class and eventually the rest of america but what he does not see is that if you build a wall people will learn to climb and by saying that Hitler and Donald trump are completely different is almost idiotic because you are so blinded by what is actually looking you in the face

This is terrifying, and of course, those who could be responsible for a wave of destruction of knowledge in the US will never read this. If you know anyone who could help prevent this tragedy from happening again, you must tell them how it happened before and is in grave danger of happening again.

For a detailed and heart-rending account of what happened under the Nazis, see “Transcending Tradition: Jewish Mathematicians in German-Speaking Academic Culture”, recently published by Springer. One example: the suicide note written by Felix Hausdorff when he knew the SS was coming the next morning to arrest him, his wife, and his wife’s sister; all three killed themselves rather than being shipped to the camps.

Thanks for the book suggestion.

My grandfather was a SURVIVOR. Suicide is surrender. He told us never to give up. He would have be appaled by anyone commiting suicide to avoid going toa camp…also, the knowledge of likely death in the camps was not known at the time.

Fortunately he had the fortitude to survive. He had great grandchildren. Many offspring in the sciences and one ( our son) who is currently studying biochemistry in Montreal.

I do not disagree whatsoever but if someone is broken you cannot fix them if you are emotionally unable to function anymore then in that situation In the concentration camps why would you want to live if you are in constant fear why would you want to carry on your grandfather along with many others were lucky to make it out of the concentration camps alive but 11 million people were not able to it is not right to say that you are enraged by someone who went through the same thing that you did but were not able to cope with the feeling of fear and hunger you cannot say that it is simply not right to dismiss the fact that we al deal with things differently to each other.

The math departments at Goettingen are fully aware of what happened there in the Nazi era. Since then, there has been some recovery so that math at Goettingen is decent. Fortunately, the library in the building Rockefeller financed is still there with its wonderful ambiance. One enters it after passing portraits of greats such as Hilbert and Noether and feels suffused by the scholarly spirit of the books, tables, gallery and students studying. Goettingen was almost completely spared during WWII because it, like Nuremberg, had had so many Americans who had studied there and pleaded for its protection.