The Benefits, and Realities, of Using Medication to Overcome Addiction

When Anna Brennan was 15 years old, her mother abandoned her in the projects of northeast Philadelphia. Her aunt eventually took her in, but Brennan struggled with anxiety and depression. She also needed to support herself, so in ninth grade she dropped out of high school and went to work at an all-night diner downtown. At 20, she met her first husband, who also lived with mental illness and had substance use issues — and gave her a tooth-marked scar in her upper right shoulder. For years, Brennan waitressed seven days a week until she had her third child, Gemma, and her back pain started, forcing her to quit.

A physician prescribed painkillers, and Brennan became addicted. Her habit quickly turned from buying pills, which were expensive on the street, to snorting and then injecting heroin, which came cheap and pure. Twelve years into their marriage, Brennan’s husband committed suicide. Then she lost her house. Brennan’s two older kids went to stay with her sister, and Brennan hasn’t seen them in over a year. “I’m a drug addict,” Brennan says bluntly. “She won’t give them back.”

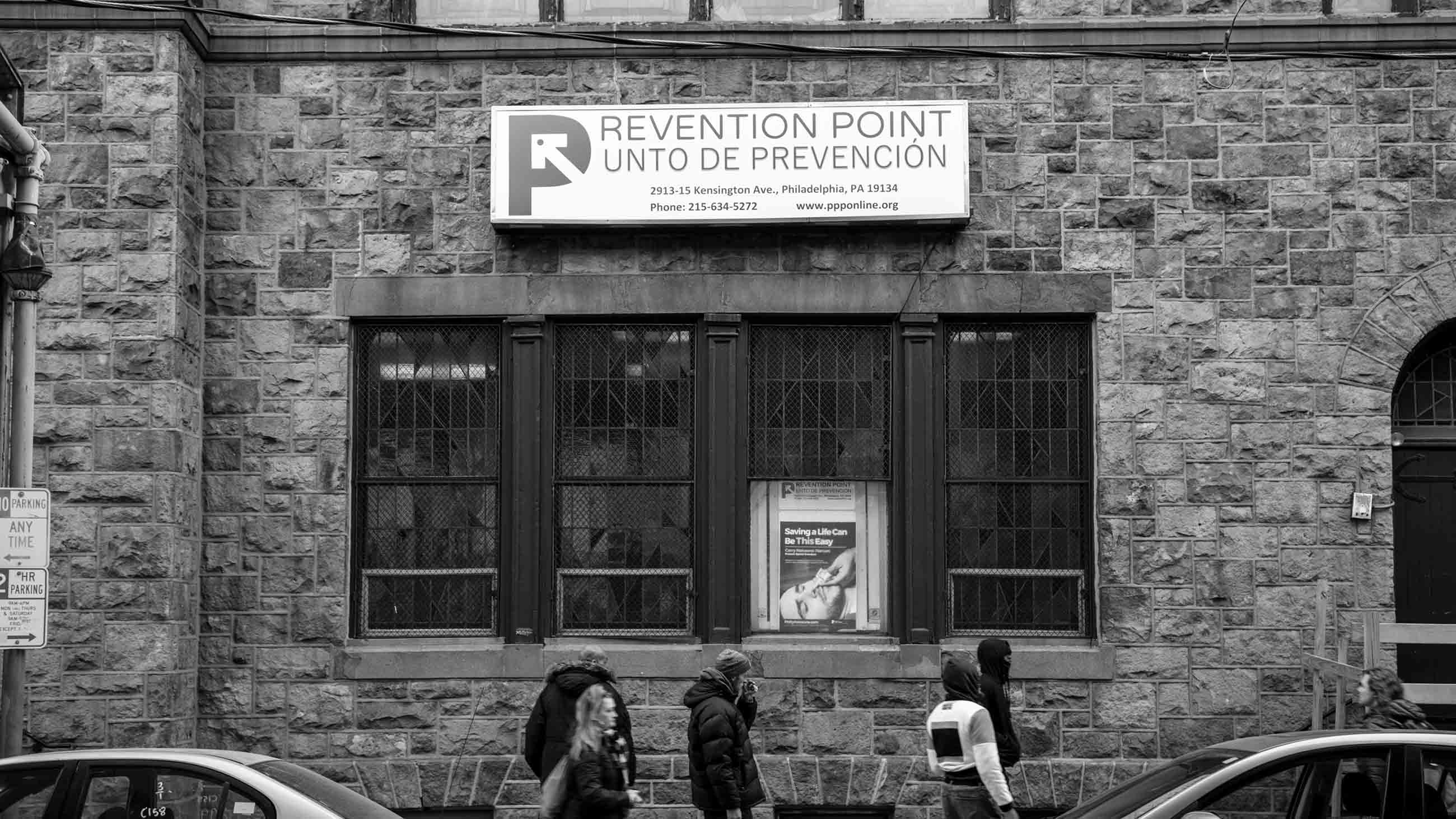

Brennan started taking Suboxone, an opioid-replacement therapy that cut her cravings and kept her from experiencing withdrawal, two different times: in 2015 and then again from 2016 to 2018. During the second round, Brennan spent more than two years making trips to Prevention Point Philadelphia on Kensington Avenue. There, she met with her case manager and the doctor who prescribed her medication. Brennan seemed poised to be a success story. But she was weighed down by the stress of coping with a drug-addicted second husband, caring for her daughter Gemma, who is autistic; and despairing that she might never see her two older children again.

“I relapsed because of depression, constantly feeling overwhelmed and hopeless,” Brennan says. Now she floats in and out of Prevention Point’s Suboxone program and sometimes sells some of her “subs” on the street when she has them and needs money, Brennan admits.

Every day in the United States, more than 130 people die from opioid overdoses, and Brennan is just one of millions of people around the country struggling to recover from addiction and avoid that fate. Studies suggest that MAT, an acronym for medication-assisted treatment (or medication-assisted therapy), is the most effective treatment approach for people with opioid use disorder. It can slice one’s risk of death in half or more. But MAT isn’t foolproof. Even on Suboxone, many people continue to struggle and relapse, particularly those who contend with trauma, poverty, and environments saturated with the very substances they are trying to avoid.

“The problem is not just heroin or fentanyl,” says Jordan Hansen of the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, the nation’s largest nonprofit addiction treatment provider. “Housing, health, jobs” — these factors and more may influence a person’s efforts at overcoming addiction. This is why some programs are now taking a holistic approach. For example, in addition to offering medication, Prevention Point connects clients with local agencies that provide therapy and housing. It also operates one of the largest needle exchanges in the country, as well as two shelters for users and an HIV and Hepatitis C clinic. The goal, says Prevention Point’s executive director José Benitez, is to meet clients where they are psychologically at any given moment, and to provide medication when they’re ready.

This type of program maintains relationships with people like Brennan, who has used Prevention Point as a resource for years and continues to see a case manager. “Our approach is: ‘Your urine is positive for substances. Let’s figure out how to make this work better for you,’” says Benitez.

“It’s not like you’re one and done.”

The oldest form of medication-assisted addiction treatment made use of methadone, which German scientists first synthesized during World War II as an alternative to morphine. Methadone clinics sprung up across the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s as soldiers with heroin addiction started returning from Vietnam. Methadone activates the opioid receptors in the brain, but by controlling the dose, doctors can keep individuals from getting high while also staving off their cravings. One drawback of methadone is that it often requires daily visits to a clinic, depending on the particular jurisdiction and its laws. Clinicians need to maintain close supervision because methadone can be addictive if not administered properly. It may take a while to find the right dose. After a period of stability, people are sometimes allowed to take methadone at home.

On the other hand, Suboxone, introduced by the British pharmaceutical company Indivior in Europe in 2006 and in the United States in 2010, is almost always taken by prescription at home. It combines buprenorphine, which activates some opioid receptors, with naloxone, a drug that blocks the effects of heroin. This combination helps control cravings and protect against overdose. Different people respond differently to methadone and Suboxone, so sometimes a little trial and error is involved in helping patients select the proper course of treatment. There’s also naltrexone, known by the brand name Vivitrol, which blocks all opioid receptors, eliminating the effects of an opioid high. It is available as a once-a-month-shot, but individuals must first detox off of heroin, a feat that some find daunting.

Many addiction advocates and people who work in the treatment field are coming to realize that MAT is the only evidence-based protocol for treating opioid use disorders. Patrick J. Kennedy, a mental health advocate and former congressman who himself is in long-term recovery from addiction, says that the appropriate use of MAT could significantly reduce death rates among people with substance use disorders. “Unless you have that craving addressed,” he says, “you can’t even get to square one to get your life back on track. When people are feeling unstable, you kind of need to give them a bubble wrap for some time.” Some people who have been using opioids for decades may need the bubble wrap of medication for the rest of their lives. Others may be able to be weaned off of it. But medication is crucial, at least in the short term, for pulling people with opioid addictions out of crisis mode, Kennedy says.

Even so, discriminatory attitudes deter some individuals from seeking it. Among the general public, says Benitez, there’s a widespread view that individuals choose to use drugs and that they can stop whenever they want. “If it were that simple,” he says, “we wouldn’t have an issue.”

Of course, neither is MAT. In 1992, Prevention Point Philadelphia was founded as a syringe exchange program. The aim was to reduce the transmission of HIV and other blood-borne infections associated with drug injection. Over time, its services expanded with the goal of reducing the many harms associated with substance use — as well as the triggers that can drive even promising MAT patients back into their addictions. “We don’t just do drug and alcohol counseling with people,” Benitez says. “We ask people to go see a therapist. It’s a long-term approach. What we’ve found is that when we have people in therapy at the same time [as taking Suboxone], the success rate is boosted.” Therapy provides an opportunity for clients to address other aspects of their lives, not just drugs and alcohol.

Funded by the city and private donations, Prevention Point is housed in a former church on a boulevard populated by sex workers, drug users, bustling bodegas, and a clattering overhead train. Benitez’s office is on the top floor across from a sanctuary that a religious group uses for Sunday services. Downstairs is a labyrinth of exam rooms and cubicles where case managers and other staff work and where clients meet with the doctor and case managers. At 7 a.m. each day, the immense side doors open to allow patients to come in for appointments or to hang out in the drop-in center, a large room where TV, coffee, food, and social support provide a break from the streets. In the adjacent room, three times a week, staff receive used needles and pass out new syringes. Prevention Point distributed approximately 2.8 million syringes in 2017.

When a participant first starts Suboxone at Prevention Point, they come to the clinic once a week. After a couple of weeks of drug-free urines, people graduate to every two weeks, then every three weeks, then once a month. This aspect of the treatment is important for people like Brennan, who have childcare issues and can’t make it to a clinic every morning. On the other hand, since most of the clients who visit Prevention Point are homeless, hanging onto medication can be dicey, making Suboxone treatment impossible.

“There are clients who are homeless and are perfectly fine taking Suboxone,” says Tracy Esteves Camacho, Prevention Point’s case management coordinator. “There are others who maybe aren’t around the safest people, who tend to get it stolen. So those higher risk people may eventually realize, ‘I can’t hold onto the medication for one reason or another, so methadone may be a better option for me.’” Because Prevention Point wants to be a “low-threshold” clinic where clients can receive MAT with the fewest barriers in their way, it does not yet offer methadone. Some clients have dropped out of the Suboxone clinic to seek different treatment elsewhere. “But for the most part we have a steady group of people,” says Camacho.

Those who are successful on medication have radically reduced relapse rates. In the first long-term follow-up with patients who were on Suboxone, half reported they were abstinent at 18 months, and 61 percent reported abstinence at three-and-a-half years.

However, whether a client is taking Suboxone, methadone, or Vivitrol, medication-assisted treatment is not a cure-all. For many, the path to recovery is riddled with relapses, and it doesn’t always end in success. Housing loss, abusive relationships, unsteady employment, and myriad other issues can trigger a return to drug use. In addition, unresolved past trauma, which a person may have been self-medicating against, can continue to plague them until they have an intense enough need to start using drugs again.

“We’re trying all kinds of ways to offer a low threshold and to ask patients, ‘What is it that you need? What’s going to make you more comfortable? What is going to make you successful?’” says Benitez. Sometimes this means acknowledging that not everyone is ready for MAT, in spite of how precarious their lives may be.

In some ways, Brennan’s story is a classic example of how poverty, housing insecurity, lack of a social network, and past trauma can feed addiction. “My mom was a bad alcoholic,” Brennan recounts. “My dad died the day after I turned 7. I have siblings I wasn’t raised with. I was raised by my mom alone. She worked at night and slept all day.” When Brennan was 15, an eviction notice arrived, so her mother went to live with the father of one of her other children. “She told me to watch the stuff in the house until she came back and got it,” recalls Brennan. “She never came back. And I’ve been on my own since then.”

Despite her best efforts, Brennan’s life has continued to bounce from one crisis to another. She has served two short jail stints since June for failure to appear in court for preliminary hearings about drug charges. She said she was dope sick both times. The last time Brennan went to jail, agents from the sheriff’s department had knocked on her door at 1 a.m. to arrest her. Both times, Brennan had to leave Gemma in the unstable hands of her second husband, Angel Rivera. “It was a mess. Angel wasn’t answering his phone,” Brennan says.

Brennan is unemployed now, her criminal record making finding a job especially difficult. Her only income is welfare and Supplemental Security Income checks. Recently, Brennan says her landlord has been trying to kick her family out of their row-house, causing her stress to spike. All of these factors are thwarting Brennan’s ability to stay on MAT and get into long-term recovery instead of relapsing over and over again, each time risking death from overdose.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Brennan says. “I’m not worried about myself. I’m just worried about Gemma. That’s all I worry about … I want to hang myself, but I can’t. My children already have one parent who killed themselves. I really understand why my husband hung himself now. I really do.” Brennan is prescribed medications for her depression and anxiety but says she doesn’t take them because they make her tired.

“This is what I think sometimes: things happen to certain people because others won’t survive it,” Brennan says.

Research shows that addiction is far more common among those, like Brennan, who earn less than $20,000 a year compared to those who make $50,000 or more. Survey data also indicate that the addiction rate among people who are unemployed is about 50 percent higher than among those who are employed. According to a literature review of more than 130 relevant studies, those with substance use disorders are less likely to find and hold down a job, and unemployment is a major trigger for developing an addiction, as well as for relapse.

Furthermore, trauma can play a dual role in addiction since those who suffered childhood abuse may self-medicate as they get older, while those who develop substance use disorders inevitably experience trauma as a result of their addiction. In some sense, childhood trauma becomes secondary to the trauma addiction breeds. People may enter the sex trade to make money for drugs or in exchange for drugs. People experience violence in the streets. Most become isolated from their families, feeling that they have burned every bridge, that they have nowhere else to turn. Some fall into destitution and find themselves experiencing homelessness, scraping to get their next fix. “If you develop a full-blown addiction, you’re going to have trauma whether or not you had it before,” says Deb Beck, president of the Drug and Alcohol Service Providers Organization of Pennsylvania. And so it is very difficult to recover and easy to slide backward.

Despite her life history, Brennan says she feels safe at Prevention Point, where she knows many of the staff. Even though she has relapsed, Brennan continues to receive medical care there and to see a case manager, who offers guidance on issues like how to deal with her landlord.

That sort of holistic, non-judgmental approach is sorely needed, say some people in the treatment community. Relapses are part of the disease and are to be expected. The Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation adopts the view that it is unethical to kick people out of a treatment program simply because of relapse, says Hansen. Instead, when a relapse occurs, care providers meet with the individual to discuss what happened and adjust the treatment plan as necessary.

Adam Brooks, who oversees research at the Public Health Management Corporation in Philadelphia, a nonprofit institute with a mission of building healthier communities, says that addiction treatment in the United States is inappropriately designed around an acute-care model. He suggests that we should think of addiction as a chronic condition like diabetes or asthma. “Let’s say you’re a patient, and you’re injecting heroin multiple times a day,” he says. “We get you onto a methadone program, and you now only inject heroin once a week. I think we could all stand back and say ‘Wow! That’s a huge change and success for that patient.’ You might be stuck like that for months or years … But anybody in the public health world would say, ‘Oh my gosh, that worked so well!’”

The experience of 69-year-old Donald Pratt shows how medication-assisted treatment combined with other supports can foster a successful recovery. The first time he used heroin as a teenager, he got sick and walked away. Then two weeks later, he tried it again. “It’s crazy,” Pratt says. “You fall in love with it. The highs, you know, I can’t glorify it. I don’t like doing that. But there’s something about it that once it gets you, you’re got. And it’s hard to say, ‘Well, that’s it.’”

Pratt’s nickname became “Two Guns” because he held a pistol in each hand when he was sticking up banks and other places to get money for drugs. “My life was complete violence,” Pratt says. He did 24 years of hard federal time, not counting the stretches he spent in jail.

Pratt also did 32 detoxes and 22 rehab programs, few of which included MAT. At one point, Pratt even graduated from a year-long inpatient treatment program. “And the next day, I went back out and did what I always did.”

But now, after nearly 40 years of drug use, Pratt has been in recovery for two years. With the help of the Suboxone program at Prevention Point, individual therapy, and 12-step group meetings, he is able to run a store six days a week. He shares an apartment with his sponsor. Every Sunday, he goes to the Rock Ministries, a church on Kensington Avenue that he has attended for nearly four years, longer than he’s been sober.

It’s likely no coincidence that Pratt has found success with this combination of supports. In an update last year to a landmark U.S. Surgeon General’s report, “Facing Addiction in America,” Elinore McCance-Katz, Assistant Secretary for Mental Health and Substance Use for the Department of Health and Human Services, proclaimed that MAT, combined with therapy, is the “gold standard for treating opioid addiction.” An abundance of evidence shows that people who use Suboxone have a reduced chance of death and stay in treatment longer than those who don’t take it. A recent study of adult users in Massachusetts published last year in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that people who survived opioid overdoses who were put on methadone had a 59 percent mortality reduction compared to those who received no medication for opioid use. Those who went on buprenorphine had a 38 percent mortality reduction.

In fact, medication-assisted treatment is far more effective at getting people into long-term recovery than behavioral interventions alone. Behavioral interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy and group meetings based on the 12-step model of recovery that originated with Alcoholics Anonymous. Eighty percent of people who use only these treatments without MAT return to drug use. But it’s hard to shake out of the public consciousness the idea that the abstinence-only, 12-step approach is the best way to treat addiction.

Even the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation still calls itself a 12-step-based program. But it has a “multitude of offerings and believes in many pathways to recovery,” Hansen says. The nonprofit added MAT to its protocol in 2013. “It was a heavy lift for us,” Hansen admits. Hazelden Betty Ford had traditionally operated on an abstinence-only, 28-day treatment model, and many people viewed medication as merely trading one drug for another. But at some point, the evidence just became too overwhelming. Now Hazelden Betty Ford offers a comprehensive opioid response: 12 steps, medical care, MAT, mental health therapy, and peer engagement. Lately, the largest part of their system is the outpatient component where individuals may get MAT, medical treatment, and peer support. The goal is long-term engagement, Hansen explains.

Despite its relative effectiveness, medication-assisted treatment is still underutilized across the country. Less than half of private treatment programs offer it, and only one third of patients in these programs actually receive it, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Just recently, the NIH confirmed the underutilization of MAT, indicating that in the first year following an overdose, less than one third of patients were given any medication for their opioid use disorder. In this sense, places like Hazelden Betty Ford and Prevention Point may be instructive because they offer a glimpse of what evidence-based addiction treatment might look like in the years to come.

Of course, just like the road to recovery, the road to addiction is a long one. Brennan’s husband, Angel Rivera, for example, says that as children, he and his three siblings bounced from home to home, sometimes with their separated parents, other times with various aunts and uncles. “It was depressing,” he says. “When you’re in school, when you’re growing up, you hear about family — that perfect family picture, that perfect family photo, white picket fence and all the family around hugging each other and stuff like that. And you ain’t have that. You can’t have a family photo because your family is scattered.” At times, the four kids were homeless, Rivera says, sleeping with their father in his van.

Rivera says his drug use started when he was 24. He’s 42 now. “So do the math. I’ve used for a long time. And I used everything, but heroin became pretty much my drug of choice. I wish I didn’t do it, but it is what it is. You on the street, you just you end up doing heroin.”

Angel says he tried quitting cold turkey and easing off with methadone. Neither worked, but he eventually found his way to Prevention Point’s Suboxone program. Before landing in the hospital for a MRSA infection in his spine last winter, which doctors said he contracted through injection drug use, Angel had logged eight months sober, his longest stretch yet. But given his traumatic background and living in the Badlands section of North Philadelphia, Rivera admits that staying off drugs, even on Suboxone, will be hard.

“There are so many triggers and temptations around you,” he says. “It ain’t just them outside saying they have it. It’s the needles on the floor. You see a bag, even just a clear plastic bag, and you want to do dope.”

Brennan agrees with Rivera that staying sober in her drug-infested neighborhood is nearly impossible. “I pick up needles all the time,” she says. Brennan recently kicked out all the users from the abandoned building adjacent to her house. She chained the door. But they climbed through the window. “I had to open the door to let them the fuck out.”

When Brennan was working with Gemma on her speech, trying to get her to say “worm,” Gemma kept insisting the word was “works” — a slang term that denotes drug paraphernalia. Gemma hears it “when we walk and everything else,” Brennan says. “I say, ‘No, it’s a worm.’ ‘It’s a works!’ she yells.”

Brennan continues to use, and she’s not sure if she wants to get back on Suboxone. She said it worked for a while but never addressed her back pain. She has heard that methadone, in addition to quelling cravings, also acts as an analgesic, and so Brennan is thinking about trying that.

A little over five years ago, she did a culinary program through Philabundance, the area’s largest hunger relief organization. She was chosen to intern at Moshulu, a high-end Philadelphia restaurant. Brennan says she is a very good cook and baker. She still has her references and progress reports from the internship.

One day she might go back to work in the food service industry, Brennan says. One way or another, she would like to recapture a feeling she has experienced only once: “I never knew what it was like to be happy honestly ’til I was 32. I got a room and I was working. I wasn’t on drugs at the time. I was completely sober. I wasn’t on nothing. That was the only time I was actually happy. That’s the only time in my life I was happy.”

Courtenay Harris Bond is a freelance reporter and writer whose work has appeared in The Philadelphia Inquirer, as well as on Philly.com, NewsWorks.org, The Broad Street Review.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Eighty percent of people who use only these treatments without MAT return to drug use. But it’s hard to shake out of the public consciousness the idea that the abstinence-only, 12-step approach is the best way to treat addiaction.

May I know where are you getting your stats from? We have very different results very strong numbers without MAT 12 Step approach model.

Disappointed that, as far as support groups, this piece is entirely 12-step. Nothing about “secular” sobriety groups like Lifering Secular Recovery or SMART, both of which are more open to MAT than AA/NA.

This is NOT “one of the best articles on the subject of addiction.” It’s just another of the merry-go-round rackets that don’t work, never have worked, and simply – in the best of cases – get people hooked on another drug in place of the very non-toxic effects of heroin, morphine, opium, etc. These other things probably do liver damage and do nothing to actually get people from “taking things.”:

If this is such a good article, why is no mention made of the success Leary and others had using LSD back before it was idiotically outlawed. Why is there no mention of the current entheogenic approaches being made currently at Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and surely other places?

LSD, psycilobin and perhaps ibogane (which I’m hearing more and more about) render 80% success rates in the studies done in the 60’s. Why did it not continue to be used? One reason is these “addiction centers” are treadmills which provide an endless supply of money from insurance, state coffers, and whatever other interests are involved.

This article reflects very, very antiquated thinking.

Not so sure LSD was “successful”. I don’t imagine it would help people on heroin to go from being addicted to an opiate to psychotic, since the effects in each individual are unpredictable. Get real.

Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone) will cause withdrawal in persons taking opiates. Starting Suboxone requires patients to be in mild opiate withdrawal when starting the drug.

Any street value for Suboxone is perplexing. As a drug of abuse, it would be limited to persons not currently tolerant to opioids, as it would only induce withdrawal in heroin addicts.

Reply

Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone) will cause withdrawal in persons taking opiates. Starting Suboxone requires patients to be in mild opiated withdrawal when starting this drug.

Any street value for Suboxone is perplexing. As a drug of abuse, it would be limited to persons not currently tolerant to opposites, as it would only induce withdrawal in heroin addicts.

This is one of the best articles on the subject of addiction and its complexities that I’ve read. Thank you. I read it on a day when my oldest child lost another friend to heroin. I hate this disease. No one is immune.

I agree with you completely. Hell, the first young woma s life started of similar to my own. I certainly know the train wreck life I’m living is chaotic and I hate it as much as anyone else would. But if you have no support system what do people suggest those who don’t do?