America’s Misguided War on Childhood Lead Exposures

In August of 2013, Shecara Norris moved with her husband and five young children into a rented colonial house in East Columbus, Ohio. She was in her late 20s and pregnant with her sixth child. The house was in a crime-ridden area that Norris describes as the “heart of the hood,” but it also had a lot of appeal, with wood floors, a dining room with a fireplace, and plenty of room for her growing family. Her son Michael — who had been born earlier that year — was a healthy baby with a strong personality.

Shecara Norris with her son Michael, whose blood lead levels were once six times higher than a standard federal benchmark. Lowering that benchmark further, critics say, will make it harder for children like Michael to get the resources they need.

But around the time of his second birthday, doctors found lead in Michael’s blood. At 30 micrograms per deciliter (mcg/dL), his blood lead levels were six times over the amount that triggers case management recommendations by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State and local public health officials were notified, and Norris and her husband were told it wasn’t safe for Michael to remain in the house, though the family didn’t have the money to leave.

To Norris, the diagnosis initially came as a shock, though it seems less surprising in hindsight. The house dates back nearly a century, to a time when lead paint was used routinely. Inspectors would later find that nearly every room was contaminated with the toxic metal, as were the front porch and the yard where Michael and his brothers and sisters would play. Lead is much more dangerous to young children than adults, targeting developing nervous systems and progressively lowering intelligence with increasing doses. All the Norris children had lead in their blood, but Michael’s levels were by far the highest. After being sent to live with his godmother until the family could find a new place to stay, Michael soon became uncontrollable: He threw frequent temper tantrums and pulled at his hair obsessively “like he was trying to get something out of his head,” Norris recalled. “The doctors said lead messes with nerves in the brain and causes kids to have behavior issues and that’s what we thought was happening.”

An estimated 37 million houses and apartments in the United States are still coated in lead paint, and each time a child like Michael is found to be exposed, it can trigger an expansive and crucial protocol of intervention. Rules vary from city to city, state to state, but lead poisoning requires swift action that can, depending on the severity of a child’s exposure, involve a host of health department officials, case managers, primary care physicians, housing investigators, and other personnel. Homes and buildings suspected of being ground zero in the exposure must be inspected and remediated, parents and other caregivers need to be educated on what a child’s exposure means and how to deal with it, and depending on the precise blood lead level, the exposed child may need some combination of medical evaluation, treatment, nutritional assessment and dietary modification, and ongoing cognitive and developmental surveillance.

It’s a necessary battery to ensure the health and wellbeing of the most vulnerable, but it’s also expensive for many cash-strapped jurisdictions — particularly those in low-income areas, where lead exposures are most acute and resources are few. And that’s precisely what has some scientists worried about a looming revision to the CDC’s benchmark childhood blood lead level figure, which is slated to be ratcheted downward in coming months. While seemingly in the best interest of children and their families, the move, critics argue, could make it harder for children like Michael to get the interventions that they need when they do get poisoned.

While not legally binding, local municipalities look to the CDC’s thresholds, which the agency has steadily lowered over time, when setting their own standards for lead responses. Today, the reference level sits at 5 mcg/dL of blood — a level at which, most experts agree, it is already impossible to predict or even detect neurological effects in any one child. The new reference level, to be adopted in the coming months, will be nudged still lower to 3.5 mcg/dL.

The revision makes some intuitive sense. No exposure to lead, however trivial, can be considered entirely safe. Still, critics say the move will also sweep hundreds of thousands of additional children into already overburdened case-management systems each year. Moreover, clinicians working with the most severely lead-exposed children say that federal funds for lead poisoning case management have repeatedly been slashed over the years, even as each new downward click in the minimum reference level draws thousands more children into local monitoring systems — usually from higher-income neighborhoods, and with little measurable benefit for long-term health.

In a report published last year, the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation estimated that for every child like Michael in the U.S. that tests at levels well over 5 mcg/dL, nearly 7 would test between 2 and 4.9 mcg/dL, alluding to the potential magnitude of the increased caseload.

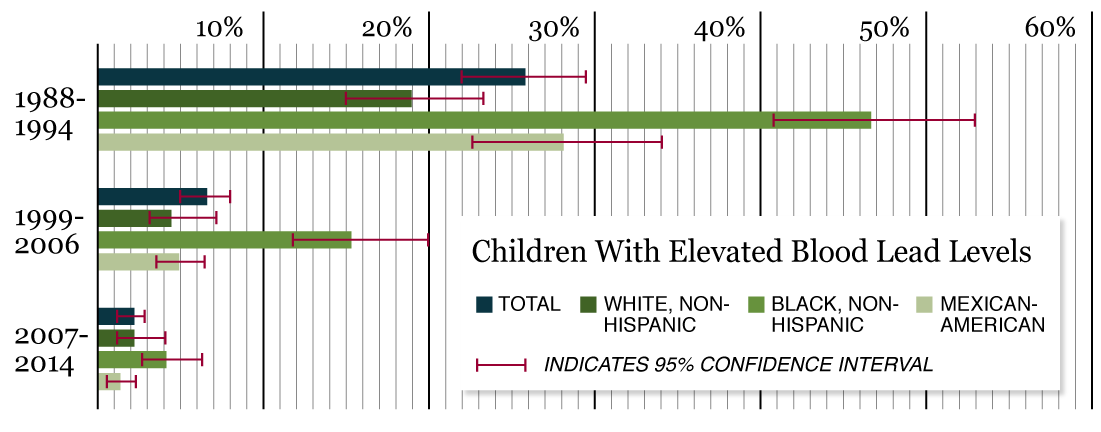

Source: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Lowering the reference level “trivializes the continuing problem of clinical childhood lead poisoning in the interiors of our major cities where blood lead concentrations in some patients are 10 times higher or more than the national average,” wrote Kim Dietrich, an epidemiologist at the University of Cincinnati and one of 16 experts sitting on a CDC panel that voted last year to make the change in the wake of widespread lead exposures in Flint, Michigan. Dietrich, who was the only member to oppose the revision, abstained from the vote, arguing that lowering the value will do little more than alarm parents. Most analytical laboratories can’t even measure down to 3.5 mcg/dL accurately, Dietrich said, so clinicians can’t be sure that reported values match up reliably with the amount of lead in a child’s body.

Dietrich’s position may seem heretical, but he is not alone in arguing that more thoughtful, systemic solutions to the nation’s lingering lead problem are needed — including not waiting for children like Michael to show up at the doctor’s office with elevated blood lead levels before taking action. Mary Jean Brown, former chief of the CDC’s Healthy Homes and Lead Poisoning Prevention Branch, and now an adjunct assistant professor at Harvard University’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, agreed. “Chasing down kids with 3.5 mcg/dL I think is a distraction from what the real priority should be, and that’s chasing down lead-contaminated housing,” she said.

For now, these arguments seem unlikely to forestall the new reference level, which the CDC and other experts say is widely misunderstood. “The new lower value means that more children will be identified as having lead exposure,” the agency said in announcing the new benchmark, “allowing parents, doctors, public health officials, and communities to take action earlier to reduce the child’s future exposure to lead.”

The revelation of Michael’s exposure is the end-product of a bizarre public policy that relies on children — too often those born to low-income families in aging housing stock — to locate homes that remain laced with toxic lead. Though a few cities and states have what are called “primary prevention” laws requiring property owners to address lead threats before young children arrive, the standard procedure is to wait for reports of elevated blood lead levels in children to surface, and then force cleanups in response. That’s called “secondary prevention,” and it plays out day after day in thousands of communities around the country.

Critics have long argued that such policies are profoundly unjust, conscripting these children and their families to essentially play canaries in the coal mine — unwitting sentries sent out to locate a hidden poison by breathing it in or ingesting it. And lead is indisputably a poison. Although children vary widely in their responses, and some tolerate high doses better than others, lead is capable of damaging every cell system it interacts with. Acutely poisoned children with levels over 80 mcg/dL will generally develop abdominal pain, seizures, anemia, and renal failure. Left untreated with chelating drugs that bind to lead and flush it from the body in urine, children can succumb to lethal brain swelling. Chelators won’t bring back normal intellectual abilities, however, and survivors of high-dose poisoning can wind up cognitively disabled, blind, or unable to walk.

CDC officials first defined the threshold for childhood lead poisoning in the 1960s as any amount in blood over 60 mcg/dL. (Today blood lead levels over 45 mcg/dL would result in hospitalization for chelation therapy). But in subsequent years, as research showed that far lower levels could impact IQ, speech, attention, and classroom performance even without inducing clinical symptoms, the CDC’s threshold fell incrementally. By 1976, when the average blood lead level of children in the United States was hovering at 15 mcg/dL, the maximum acceptable threshold was 40 mcg/dL. By 1991 — a year after leaded gasoline was banned, and long after leaded paint was banned in 1978 — the CDC reset the “level of concern” to 10 mcg/dL for children under six, and stuck with that for two decades.

According to Brown, the level of concern, which was more commonly called the “action level,” always had a fundamental problem. Because of how the guidelines were worded, many people assumed that blood lead levels below 10 mcg/dL were “safe.” But with each new year, scientists were finding that there really is no inconsequential amount of lead in a child’s body — although separating out the long-term risks of low-level lead exposure from the background noise of life in the modern age is exceedingly difficult. In aggregate sampling of large populations of exposed children, for example, all blood lead levels, no matter how small, have been linked to detectable reductions in average test scores. At the same time, that doesn’t mean individual children at the lowest exposure ranges, Brown said, “wouldn’t get into and be successful in college.”

Still, based in part on these new risk findings and persistent confusion over what an “action level” really meant, CDC officials decided to take a different tack in 2012. Instead of tying the standard to some presumed safety threshold, they adopted a statistical value that reflects how blood lead levels in American children are changing over time. They derived it from a representative sampling of 850 children between the ages of 1 and 5, each of them included in a larger national surveillance dataset. Gathered between 2007 and 2010, the data indicated that 97.5 percent of U.S. children had blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or lower, and this became the so-called reference level that still exists today. It was a way of characterizing the status quo and, by extension, shining a light on children whose blood lead levels deviated worryingly from that baseline.

The CDC’s plan was to revise the reference level every four years to keep it current with the latest blood lead surveillance data, and promote policies that would drive it down even more. The pending shift to 3.5 mcg/dL reflects how the blood lead levels in American children are still falling. Michael Kosnett, a medical toxicologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, and a member of the CDC’s advisory panel on lead, argued that the reference must be lowered accordingly so that parents will know when a child’s levels exceed the population benchmark. Then they can try to figure out what’s responsible for their kid’s exposure and eliminate it, he said.

And yet, this newer reference level concept has also confused the public, in part because the CDC recommends case management for children who test above it. Brown said the reference level is widely misconstrued as a diagnosis for lead poisoning, when it should actually be used “as a benchmark and signal about whether we’re moving in the right direction,” she said.

Media reports compound the confusion. In the wake of Flint, Michigan’s recent disaster with lead-contaminated drinking water, press reports have routinely described children with blood lead levels above 5 mcg/dL as being brain damaged. Jennifer Lowry, a pediatrician and toxicologist at Children’s Mercy Hospital, in Kansas City, Missouri, said this presents a real disservice. “It puts a stigma on these children that they shouldn’t have,” she said.

Lowry added that in her experience, most health care providers don’t understand what the reference level really represents either. “The education for what to do was non-existent,” she said of the 2012 change. Doctors assumed that 5 mcg/dL was the new action level, Lowry said, “and thought lead was suddenly more toxic than it was before.” After 2012, Lowry was pressured to do home inspections for kids who had crossed over 5 mcg/dL, “but the available resources never changed,” she said.

“We didn’t have enough when the action level was 10 mcg/dL,” she added.

That average childhood blood lead levels have declined so dramatically since the 1970s marks a public health victory attributed mostly to the ban on leaded gasoline, which historically was the dominant exposure source. Yet that same victory came with an environmental justice failure, in that America’s lead problem has since been shunted to low-income neighborhoods plagued by flaking lead paint. Black children in particular are more than twice as likely to have elevated blood lead levels as whites, and poor inner-city children are far more likely to wind up acutely poisoned than those with middle or upper-middle class backgrounds.

To bring that point home, Dietrich recently took me on a tour of what used to be a thriving, upscale neighborhood in downtown Cincinnati. Located in the city’s west end, the neighborhood was sliced in half by the construction of Interstate 75 during the 1950s and never fully recovered. This is where Dietrich spent years running a clinical trial with lead-exposed children exploring whether chelation therapy might improve their cognitive test scores. (It didn’t.)

The sun shone brightly as we walked past crumbling Florentine brownstones on a warm day in October. Many of the buildings were boarded up and abandoned, their ornate wooden trim rotting away under layers of old paint. With his retirement approaching, Dietrich seemed happy in his old haunts. A pair of local residents, both of them people of color, watched silently from a stoop across the road as Dietrich picked a paint chip off the sidewalk. “This chip is about 75 percent lead, and if I tasted it, it would be sweet,” he said. Then grinding the chip under his foot into the toxic powder of the sort that wafts through the neighborhood’s windows and doors, he looked around and added that every one of the homes on this block could poison dozens of kids over time. “It’s not one child, one house,” he said. “It’s one house and many children.”

After testing positive for lead exposure, many local children wind up across town to see Nicholas Newman. A pediatrician with the build of a long-distance athlete, Newman routinely bikes six miles to and from work at the Environmental Health and Lead Clinic at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The clinic, which Newman directs, tends to hundreds of lead-exposed children every year — a small fraction of the estimated 535,000 kids who test over the reference level in the United States.

“There’s a very big difference between a kid with a level of 70 or 80 mcg/dL who can’t walk or use the toilet and is in bed babbling and not making sense, and a kid with a level of 7 mcg/dL who runs around acting normally,” Newman told me. Of the children with the very highest levels, Newman said, “those are all low-income kids.”

Newman emphasized that there isn’t any secret formula for reducing the effects of lead. But absent other risk factors that can also degrade a child’s neurological development, such as a poor diet and a lack of cognitive stimulation, he wrote in an email, lead’s low-level effects might not even be observable, though they may still be there. When treating children, however, Newman addresses threats he can do something about: He tries to prevent further exposure, encourages parents to read to their children and stimulate them intellectually, and to make sure they eat nutritious foods high in iron and vitamin C, since children who don’t get enough of these micronutrients tend to absorb more lead. A child’s cognitive performance can improve with these steps. Long-term prospects for the acutely poisoned children are dismal by comparison, however, and worsen as their exposure durations get longer. Studies link chronic lead poisoning with academic failure, as well as aggressive and possibly even criminal behavior, which are all endemic in Cincinnati’s poorer neighborhoods.

“Suddenly we had a lot more kids who needed case management, but only one-tenth of the support we had previously,” said Nick Newman, head of the Environmental Health and Lead Clinic at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

During a meeting at his office, Newman paused thoughtfully after questions, and then gave long answers that covered a lot of ground. He recalled that just after the CDC swapped the level of concern for the reference level in 2012, Congress slashed the agency’s budget for lead poisoning prevention control by more than 90 percent, from just over $29 million to just under $2 million. “So suddenly we had a lot more kids who needed case management but only one-tenth of the support we had previously,” he said. Roughly half the funding was later restored, Newman added, but caseloads at the clinic are still growing.

Cynthia McCarthy, a senior sanitarian who works for the city’s childhood lead poisoning prevention program, shared Newman’s concerns. McCarthy’s department coordinates visits with families after their children test over the reference level. She said her caseload tripled after the new CDC value was established in 2012, but without added funding for the rigorous inspections that could find exposure sources at home. With more money, such inspections might be offered to kids who test over 5 mcg/dL. But as it stands now, McCarthy said nurses can only give advice without sending an inspector to make sure a house is lead-safe.

Now, with an even lower reference level looming, Newman worries that caseloads could grow faster and strain resources to the brink. Such worries will likely be compounded if the Trump administration’s proposal to cut billions of dollars from programs that support healthy housing and lead pollution cleanup at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Environmental Protection Agency comes to pass. Future prospects for the CDC’s lead poisoning prevention programs are unknown.

“We’ve gotten to a point where we don’t have enough to deal with the kids we already have,” Newman said. Adding more kids without a corresponding increase in funds to manage them, he said, “dilutes those resources further.”

Newman studied under Dietrich while he was working on a master’s degree in clinical and translational research at the University of Cincinnati. Both he and Dietrich are adamant that the media spotlight on Flint’s drinking water crisis, even as it revived public awareness of lead’s dangers, and of drinking water as yet another source of exposure, overlooked the larger reality of communities by the thousands facing far greater threats from flaking lead paint in antiquated housing.

To bolster the point, Dietrich referred to an investigation showing that more kids under six living in a single zip code from Grand Rapids, Michigan have blood lead levels over 5 mcg/dL than all the kids of the same age living in Flint’s seven zip codes combined. Released by the Healthy Homes Coalition of West Michigan, a community-based nonprofit group in Grand Rapids, the data affirmed that lead-contaminated homes — not lead-tainted water — were the primary source of those exposures.

Consistent with secondary prevention, most such homes come on the radar only when children test positive on a blood lead test. However, blood lead surveillance in the United States is sporadic, and many homes are never tested at all. And with high rates of rental turnover in low-income neighborhoods, incoming families can face the same lead threats as those who were the last to leave. Medicaid requires testing for children covered under that program at 1 and 2 years of age, and states also impose their own requirements. But in many states, fewer than half of all children are ever tested, underscoring the inadequacy of lead screening programs to identify problem homes.

Owners of pre-1978 housing are required by federal law to disclose lead hazards during real estate transactions, but the law also gives them an easy out: Owners can simply claim they’re unaware of lead paint on the property, and in most cases, that’s the box they check on the disclosure form because lead inspections occur so rarely, according to David Jacobs, chief scientist at the Columbia, Maryland-based National Center for Healthy Housing, a nonprofit policy and research organization that develops standards for lead inspection and remediation.

Unless state law compels them to, property owners have little incentive to test for lead, since finding it might lead to a costly remediation. What owners of older properties must do by law is provide incoming tenants or buyers with an EPA pamphlet describing how to protect families from lead. But that doesn’t always happen. If tenants file a complaint after their child’s blood test comes back positive, landlords are generally required to fix the problem. But Jacobs said that there is not always adequate case management or funding to make sure those fixes happen. Landlords also often drag their feet on repairs, he said, setting the stage for ugly disputes and the specter of homelessness for affected families.

Tenants who withhold rent in protest are sometimes evicted, and landlords might also antagonize their tenants until they move out voluntarily and then rent the dwelling to someone else. “We didn’t ask about lead — didn’t think about it,” Norris recalled. And no one brought it up when they met with the realtor before moving in, she said. After Michael and his siblings were exposed, Norris’s landlord applied for a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to help pay the cost of remediating the property. But paperwork and red tape held the remediation up for months. Meanwhile, the Norris family was accountable for rent payments, even after they’d been told that their house wasn’t safe.

Jacobs acknowledges the importance of continuing secondary, after-the-fact prevention to respond to kids who have already been poisoned. But the country’s priorities have to shift towards preventing kids from being exposed to lead in the first place. “We will never test our way out of this,” Jacobs said.

The question is whether the alternative — enforced testing and remediation of remaining lead-filled housing stock — is feasible on a national scale. Federal officials aren’t inclined to take on such primary prevention measures, given the exorbitant projected costs. I recently spoke to Michelle Miller, deputy director of HUD’s Office of Healthy Homes and Lead Hazard Control, which helps to fund state and local programs to eliminate threats from lead paint. Between 1993 and 2012, Miller’s office contributed $1.5 billion towards lead paint remediation, but even that reached just a small percentage of affected homes. The HUD office limped along with a budget of $145 million in 2017, while the price to address every one of the 37 million lead-contaminated homes in the United States “would be roughly $350 billion,” Miller said. Furthermore, she added, congressional officials have shown little political appetite for primary prevention, given the significant burdens it can impose on property owners.

Some states and local governments are exploring more proactive measures. Katrina Smith Korfmacher, an associate professor in environmental medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York, was part of a coalition to promote a primary prevention law for that city. Using existing blood lead screening data, screening maps generated in Rochester revealed neighborhoods where more than a third of the children had blood lead levels over 10 mcg/dL. Those are the types of neighborhoods and buildings that municipalities should prioritize for testing, Korfmacher said.

Rochester’s law requires property owners to obtain a certificate of occupancy deeming that their dwellings have been inspected for peeling paint and, in some areas, hazards from lead dust. Korfmacher acknowledged that the potential costs were a major concern before the lead law was passed in 2005, and could be for other communities as well — especially those with a weak housing market. Since 2000, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development has awarded around $30 million in grant funding to the city and the surrounding county to help Rochester’s property owners pay for necessary work. The city’s law has also allowed for temporary controls, such as recoating lead paint instead of permanently removing or encapsulating it. These controls may be cheaper than full lead abatement and protect against childhood exposures, although they need to be routinely checked to ensure they’re holding up. Over the last few decades, owing in large part to the local law, “our blood lead levels have come down more than twice as fast as those in other New York cities,” Korfmacher said. And contrary to dire predictions, those levels fell without breaking the bank.

Still, primary prevention strategies adopted by other cities haven’t always worked. The city of Cleveland, for instance, created a voluntary program 12 years ago allowing property owners to join a lead-safe registry if they addressed their lead paint problems proactively. Not a single one took the city up on its offer — indicating that the potential liability risk was not enough to justify the cost of certification — and the program has since been declared a failure. And even Rochester’s model doesn’t amount to a silver bullet that will work everywhere, Korfmacher emphasized. Identifying the most appropriate strategy for a given community “is the 10-million-dollar question,” she said. What seems to work for Rochester, Korfmacher said, “are community groups that watchdog the law, cooperation from the county, state, and federal agencies that support it, and a real commitment on the part of the city to implement it.

“The key element is partnership,” she said, “and really listening to the community.”

Brown said that in her view, health agencies are saddled with a medical model that doesn’t work for lead anymore. Prompted during the 1960s by activists like the Black Panthers, that model was lifesaving for acutely poisoned children who might have otherwise died without chelation therapy. But as the number of lethally poisoned children has dropped, she said, priorities need to focus on preventing intellectual impairments that don’t respond to any known interventions. Going out and saving poisoned kids was “more heroic and more glamorous” and easy for people — including congressional staffers — to understand, she said. By contrast, primary prevention, she said, deals in obscure probabilities. The idea of saying “OK, I reduce a child’s risk of repeating a grade in school by 20 percent,” Brown said, does not seem as “heroic.”

Newman agreed that policies on lead, as he explained it, should close loops when it comes to the perceived benefits of prevention. The only benefit to landlords who pay for the requisite upgrades, he said, may be that their young tenants “don’t fail math.” What property owners need, Newman said, are financial incentives such as tax deductions for lead abatement that close loops by providing more tangible returns on investment.

“We spent so many years trying to get all these kids tested,” he said, even though the point is to prevent exposure, and the source of that exposure is known.

“It’s the housing, stupid!” Newman exclaimed.

Newman said that sometimes he feels like he’s in a military hospital on the front lines, with “mud everywhere,” and compares lead policy makers to generals “in some palace, discussing in abstract ways how to win the war.” He added that the people he works and interacts with in Ohio and Kentucky “are working hard and swimming upstream — and the current’s getting swifter.”

Meanwhile, Brown’s successor as chief of the CDC’s Healthy Homes and Lead Poisoning Prevention Branch, Adrienne Ettinger, insisted that the agency couldn’t simply “ignore the fact that there is no safe threshold” for lead and that in lowering the reference level, the agency was trying to “move the bar” on prevention forward. But she also acknowledged that lawmakers and officials at every level need to do a better job at prevention overall — particularly in areas where there are high-risk kids. “Lead is a complicated issue with lots of nuances,” she said. “It touches on everything: housing, health, medicine, science, laboratory issues, politics, economics, and education.” Ettinger emphasized that word choice really matters and that some media coverage leads to confusion when using the term ‘lead poisoning.’ “We don’t use that term unless it’s for a high-level exposure,” Ettinger said.

“We need to re-educate the public and do a better job explaining where we need to go in the future,” she added.

Shecara Norris, too, has made a mission of educating people about lead, speaking to her church and the Ohio Senate about a threat that she said barely registers with the local community. Her family moved twice since leaving the house where Michael and his siblings were exposed, but every new dwelling turned out to be lead contaminated as well. Meanwhile, Michael’s blood lead levels are down to 8 mcg/dL and he’s doing well in school — progress that Norris attributes in no small part to the child’s healthy diet, which doesn’t include sugar or fried foods, and is heavy in iron-rich green vegetables. Norris is deeply religious and emphasized her belief that prayer also played a pivotal role in Michael’s steady improvement. Still, the experience of her son’s lead poisoning remains painfully vivid. “It put such a hurt and stress on my family,” she said.

Charles Schmidt is a recipient of the National Association of Science Writers’ Science in Society Journalism Award. His work has appeared in Science, Nature Biotechnology, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and The Washington Post, among other publications.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Lead is one of the great tragedies of human civilization going back to the greeks who knew it was toxic. Lead is in hair coloring, lipstick, thousands of products, we are insane for lead.

You are making a mountain out of a molehill. Of course the sources should be eliminated. But the evidence is becoming rock solid that levels well below 5 ucg/dl are toxic and cause deaths and damage.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(18)30025-2/fulltext

Concentrations of lead in blood lower than 5 μg/dL (<0·24 μmol/L) are an important, but largely ignored, risk factor for death in the USA, particularly from cardiovascular disease.

Some of us have consistently stated this position only to be abused by state and federal authorities that push to increase screening. Further, after the fiasco in Flint. The push was to spend millions of dollars to test water and spot check children rather than to fix the source, old pipes, fountains, etc.

Millions of children each day are exposed to low levels of lead exposure, but, according to the EPA model are developing elevations in blood lead levels

It is time to practice primary prevention.

Good points, Howard. If I were looking at the problem in Ohio, I would also look at soils but suspect that you can almost guess the order of magnitude soil lead level by using a historical vehicle per mile database (for those years when tetraethyl lead was added to gasoline) for a particular neighborhood.

I left the U of Hawaii before I finished the project (anthropogenic lead in Hawaii soils and coastal ocean with Eric DeCarlo) but always wanted to do a lead measurement in the playground that was underneath the H-1 interchange near the University.

I think hand-held XRF instruments that can analyze for lead are readily available (such as those made by Bruker). Testing houses rather than kids would be faster and cheaper. Then, use the Rochester approach and at minimum, ensure these high lead homes are repainted. One can obviously screen which homes to test by the age of the neighborhood and the homes in question. Just do it. Getting inner city/older neighborhoods fixed makes far more sense than throwing money at a 3.5 ug/dL approach that might tax some laboratories at their detection limits and require retraining staff in low level heavy metal measurements.

“Solutions” do exist. Certainly when funds are scarce why would interim controls be acceptable when for a lessor cost the existing hazardous lead can now be treated? Lets not forget that paint does not have an endless life span. Thus when one family may move out of a pre 78 home with lead, the new family is once again exposed to perhaps a failed application. Skeptical? Read the Ohio State University Lead Contaminated Surface Treatment Study. Hazardous lead can in fact be treated by way of lowering the bio-availability. While one municipality may acquire a HUD grant for $1.5m and treat 125 homes successfully in a community with 10,000 pre ’78 homes, doing simple math dictates it will take 80 additional years to complete the remainder of those homes. Let’s get serious.

Primary prevention of lead poisoning is a very intuitive concept.

Preventing children from being exposed to a potent toxin works better than waiting for them to be exposed to a potent toxin.

There is clear evidence that the approach is effective, especially in communities with high incidence of exposures. CDC can help with clear(er) guidance, HUD can help with more targeted funds, EPA can help with a greater focus on enforcement. Several states have taken the lead in developing primary prevention programs. like Maryland, Massachusetts, NY and Rochester NY. More States and communities can help with a new, smarter focus on housing code actions. The list goes on….

But, in States with older housing, the scope of the problem is daunting.

But waiting because the problem is so large isn’t a good solution.

Thank you for the most insightful article on lead that I’ve read in a long time.

It is completely possible now to effectively seal and treat hazardous lead in these homes. Treat by way of lowering the bio-availability of what’s allowed to absorb into the bloodstream. Cost effective, easy to apply, much better than regular paint. Don’t believe it? Contact me directly for the unbiased OSU study demonstrating such claims. [email protected]

Excellent piece! Thank you. And thank you to Howard Mielke and any other experts who join in with guidance and further insight.

I have a question re:

“The only benefit to landlords who pay for the requisite upgrades, he said, may be that their young tenants “don’t fail math.” What property owners need, Newman said, are financial incentives such as tax deductions for lead abatement that close loops by providing more tangible returns on investment.”

Is there an organization or individual who is working on just this? Trying to change the minutia of the tax code and the way insurance works in the interest of lead poison prevention?

It seems to me that right now there are only the courts. The huge liability case in California (and Rhode Island, previously). Class action suits revolving around environmental health/injustice. And individuals suing their neighbors for negligence.

tbeller at tulane.edu

I have just finished reading this article. My eyes fill with tears for this family and all the families affected by lead poisoning. I also feel anger at the inertia that continues to play out on nothing changing to protect our vulnerable population. I am an R.N. who does home visits to lead exposed children & their families. I present workable solutions the families can be successful at as Dr. Newman does(diet, minimizing further exposure, parent-child interactions).

Let me echo the fact that goals for elimination of exposures have to be set, standards must then be adopted and enforced to support the goal of prevention and that starts with housing (paint, soil and water). Testing (visual and clearance) homes, schools and child care centers are critical and must be done before occupancy, rental or sale and upheld annually if possible. I urge all to look to Maryland for the one of the most comprehensive and proven set of standards and results. It has proven to be far more effective and sustained than any program in the Country. In short Maryland is focus on clean up of hazards before occupancy for all pre 78 rental housing, requires inspection, intervention and clearance testing before occupancy and during occupancy if hazards such as chipping paint (leaded or not) occur. Maryland also prohibits landlords from using the rent court to collect rent if they are out of compliance with the Maryland law. And through state enforcement of federal renovation rules (RRP) are ensuring actions to protect homeowners and require clean up. Maryland put provisions on drinking water for schools and standards for child care centers. In short, Maryland has reduced lead poisoning cases by over 98% and has done so by having strong enforcement by the State and local courts – where enforcement actions require full abatement for all properties owned by a person, corporation, partnership or LLC. We also must have government agencies and banks stop reselling leaded homes back into vulnerable communities. And we need to ensure federal agencies like HUD and the Department of Energy place as a top line priority the replacement of every leaded window in America. Please read the Blueprint for Action to Eliminate Lead Poisoning Published by http://www.greenandhealthyhomes.org

A strategy that relies only or significantly on testing children chases the ball down hill and will never catch up. Thank you to Charles Schmidt and Undark for publishing this article, and to the many quoted who pointed this out. We learned this lesson from Flint, and let it not be in vain: the problem starts with widespread exposure, not the poisoning. The exposure is the problem to be solved – the poisoned children are simply the tragic result of that problem. The way to solve this problem is to stop exposure and the focus must be there, not solely on elevated blood lead levels. Whether the source is water, paint, dust, or soil, the solution is found in testing children’s environments before the are poisoned.

Government has a significant role to play in keeping children safe from lead. But those responsible for creating this hazard should also be held accountable – as well as those who allow known hazards to persist. How children get exposed to lead is well understood. So we urgently need to start assigning responsibility, holding polluters accountable, and closing loopholes that allow people to plead ignorance or ignore their due diligence and refuse to find out if older homes contain lead.

It’s an expensive problem. Those costs should and can be shared so that we can all reap the benefits of children growing up healthy. And certainly the last ones to pay the price, which they pay so dearly under the current response, should be children.

.

What will come to pass is landlords advertising “lead-remediated” rentals for say, a 60% higher rent. That will push everyone else to comply. Of course, all the rents then will be maybe 50% higher than at present, adjusted for inflation.

.

Couldn’t help but notice the yellow Pelican case. These lead hazard demonstration kits were created by Ohio Department of Health staff in the Lead program.

Prevention is absolutely the best policy for protecting our children from the toxic effects of lead. That is true for paint, dust, and soil. It is also true for water.

More and more communities are finding lead in drinking water – including at schools and child care facilities where our children to go learn and play each day. It’s time to stop waiting for more test results. It is time to remove lead-bearing pipes and faucets, and install certified filters to begin protecting children immediately. In short, it’s time to Get the Lead Out.

To follow up on Dr. Jacobs’ suggestion that we hold the lead companies responsible: For decades after the lead companies – including NL Industries, Sherwin-Williams, ASARCO and Eagle Picher – knew that lead paint and pipes could cause lead poisoning they continued to sell those deadly products. (see “Warnings Unheeded: a history of child lead poisoning,” American Journal of Public Health, 1989 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1349776/ and

The Lead Industry and Lead Water Pipes: “A Modest Campaign”; Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1584–1592) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2509614/ )

Addressing lead paint problems includes remediation of not only lead paint, but also lead-contaminated dust and soil. The costs of doing this are not as high as this article suggests. A recent report from Pew Charitable Trusts and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (that I worked on) shows that an investment of $2.5 billion will result in benefits of at least $3.5 billion or at least $1.39 for each $1 invested (see p 45 of the report at http://www.nchh.org/Policy/10Policies.aspx ). This investment means the nation needs to increase funding for the HUD lead and healthy homes program and find ways to stimulate funding from the private sector, philanthropy and others. Why not hold accountable those who created this mess in our homes in the first place—the lead paint companies and the lead industry? Rather than focus on what a certain blood lead level means, we should focus on solutions. These solutions exist and have been proven and should be implemented to prevent exposures before they harm our children.

Addressing residential lead paint hazards includes remediating lead paint, lead-contaminated dust and lead-contaminated soil, not only paint. The costs of doing this are not as high as this article suggests: A new cost benefit analysis published just last year by Pew Charitable Trusts and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (that I helped with) shows that investing $2.5 billion would result in at least $3.5 billion in future discounted benefits, or at least $1.39 for each dollar invested. see p. 45 of the report at http://www.nchh.org/Policy/10Policies.aspx The nation should devote more resources to addressing the root cause, which means increasing funding for HUD’s lead paint and healthy homes program and promoting private sector and philanthropic funding. Why not also hold accountable those who created this mess in the first place–the lead paint and lead industries? Rather than focus on what a certain blood lead level means, we should focus on solutions. These solutions exist, we only need to implement them.

There is a major missing factor in the article because it focuses only on lead-based paint. The focus on paint is misguided. The lead exposure of children is due to all sources of lead dust. In New Orleans we can account for at least ten times more lead dust from the use of tetra-ethyl lead additives during its use in gasoline than we can account from power sanding off the lead-based paint of every old home in New Orleans. Lead dust from all sources accumulated in urban soil and it becomes re-suspended into the air during late summer when soils dry out. The late summer inhalation of lead aerosols from contaminated soil drives blood lead levels. Research conducted in New Orleans before and after Katrina indicates the extraordinary effect that the soil lead reservoir has on children’s lead exposure. The seasonal influence of the lead dust reservoir on the children is shown in Michigan, including Flint before the water fiasco.

References:

Mielke HW, Gonzales CR, Powell ET, Mielke PW Jr. 2016 Spatiotemporal dynamic transformations of soil lead and children’s blood lead ten years after Hurricane Katrina: New grounds for primary prevention. Environment International. 94:567–575;

Laidlaw MAS, Filippelli GM, Sadler RC, Gonzales C, Ball AS, Mielke HW. 2016. Children’s Blood Lead Seasonality in Flint, Michigan (USA), and Soil-Sourced Lead Hazard Risks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 358; http://doi:10.3390/ijerph13040358

This is one of the most spectacular articles on lead hazard I have ever read. Thank you, Charles Schmidt. In my hometown of Kalamazoo Michigan, the city commission has set a goal of eliminating generational poverty – a laudable dream. I think, as a historic preservationist, that this goal must include both minimizing the lead hazard AND saving older homes.