In the Fight Against Obesity, the Real Enemy Is Oversimplification

All over America, public health campaigners are urging their fellow citizens — especially children — to cut back on sugary drinks and to eat foods with less added sugar. Cities like Berkeley and Philadelphia have levied taxes on soda, the Food and Drug Administration will soon require food labels to include information on added sugars, and schools around the nation are banishing soda from cafeterias and vending machines.

The sugar industry worked overtime to ensure that sugar was a welcome part of any diet. Today, it’s Dietary Enemy No. 1. Either way, Americans have gotten fatter.

Sugar does make a terrific dietary villain. It’s easy to identify, it has no redeeming nutritional value, and it’s backed by large companies that have spent billions both advertising it and underwriting scientific research that gave sugar a clean bill of health for decades. And the eat-less-sugar message is getting through. Since 1999, Americans have cut sugar consumption by 14 percent. Much of that reduction has come from soda, which adults and children are drinking less of.

There’s just one problem: We’re not getting any thinner. The most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, from 2014, show an 8 percent increase in obesity in just two years. So an ingredient is identified as a problem, people eat less of it, and nothing really changes.

If that pattern sounds familiar, perhaps you remember that sugar wasn’t always Dietary Enemy No. 1.

Based on research done in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, the virtues of cutting back on fat were a bedrock part of the nutritional canon. In 1968, the American Heart Association issued eight dietary guidelines, and the only specific recommendations were to reduce animal fat, replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat, and reduce cholesterol. All the others were general advice to maintain “ideal” body weight, to develop “sound food habits,” and to start doing so early in life. The first two versions of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (1980 and 1985) likewise said, “Avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol.” (They also said “Avoid too much sugar,” but the emphasis there was on dental health.)

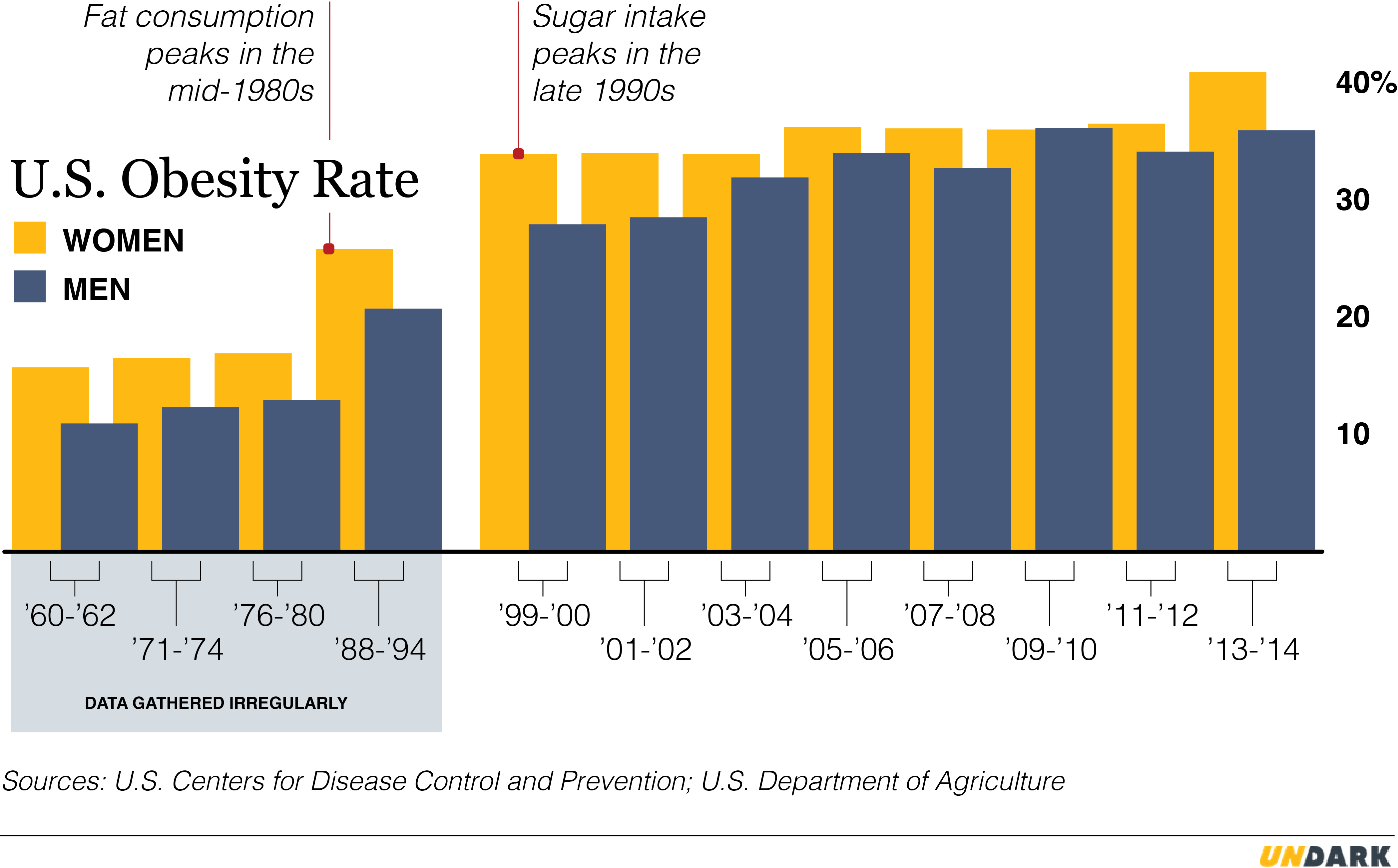

As a result, Americans did consume a bit less fat. Our intake peaked in 1986, at 43 percent of calories, and decreased gradually to a low of 38 percent in 1997. And yet, over that same period, we got much, much fatter, with the obesity rate going from 22.9 percent of the population to 30.5 percent. By 2010, the last year for which USDA data are available, we were back to 43 percent of calories from fat.

The data on sugar are strikingly similar. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, sugar consumption is down from 427 calories a day in 1999 to to 366 in 2014. In that time, the obesity has gone from 30.5 percent to 37.7 percent. Not quite as big a jump as during the less-fat days, but awfully close.

Still, these two pieces of advice — neither of which seems to have had much impact on public health — are the stuff of an acrimonious battle in the nutrition community, with some of the staunchest advocates for reducing sugar intake being the harshest critics of fat reduction advice. Take Robert Lustig, a pediatric endocrinologist and professor at the University of California, San Francisco. When it comes to the importance of eating less sugar, he wrote the book: “Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity, and Disease.” He argues that a fundamental misreading of nutrition research of the 1950s and 60s led to the “eat less fat” recommendation and that “the low-fat diet is what got us into this mess” of obesity and disease. Meanwhile, sugar, which Lustig claims is “toxic” in the quantities Americans eat it, sneaked into product after product.

It’s no paradox that sugar consumption is down but obesity isn’t, Lustig wrote in an email: “Sugar accounts for only about 10 percent of weight gain,” so small reductions aren’t “likely to make much of a difference in weight or obesity rates.” Instead, the problem lies in the way we metabolize one particular sugar — fructose, which makes up about half of the two major sweeteners, table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

Fructose is the “driver of metabolic dysfunction, unrelated to its calories and unrelated to weight gain,” Lustig says. It wreaks havoc with our endocrine system, raising the risks of heart disease and diabetes.

While it’s true that new diabetes diagnoses have dropped since 2009, in tandem with the decline in sugar consumption, there’s not widespread agreement on Lustig’s take on fructose. Luc Tappy, a professor of physiology at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland and a member of the government-sponsored committees crafting developing dietary recommendations both there and in France, calls the metabolic impact of fructose an “open question.”

Regardless, pretty much everyone agrees that eating less sugar is a good idea. You don’t have to believe in the metabolic dysfunction theory to think it’s smart to curb your intake of nutrition-free calories.

Fat is more complicated. According to Alice Lichtenstein, vice chair of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, there’s general agreement that mono- and polyunsaturated fats are healthful and trans fats are not. Saturated fat, though, has made headlines as scientists re-evaluate its role in disease. Even though the “majority of the data” supports limiting it, says Lichtenstein, the issue is “controversial and confusing.”

But the two pieces of advice have something in common, something important enough to undermine the effectiveness of both, regardless of the consensus or lack of it: They’re both focused on just one component of our diet. Eating less sugar, in particular, may be necessary, but it is certainly not sufficient. Yet because everyone agrees on it, that advice dominates the nutritional agenda, drowning out more nuanced or broad-spectrum advice.

“Partitioning macronutrients into good and bad guys is a big mistake,” Tappy says, because nutrition is complicated. The effect of those macronutrients “varies according to food consumed,” and you can have an excellent diet that includes them or a lousy diet that doesn’t.

Look at any diet that has gotten traction in the last 30 years, and it’s likely to be about just one thing. It’s fat. It’s carbs. It’s gluten. It’s meat. Although the diets generally include recommendations about overall patterns as well, the one-thing advice dominates: All you have to do is not eat that, and you’ll be fine. The fatal flaw in such advice is that it’s much too easy to do that one thing and still eat badly. “People don’t listen to advice unless they can follow that advice and still eat what they want,” says Michael Jacobson, co-founder and president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy organization that has campaigned for reducing sugar consumption through measures like soda taxes and removing sugary beverages from schools.

Marion Nestle, a professor of nutrition, food studies, and public health at New York University and the author, most recently, of “Soda Politics: Taking On Big Soda (and Winning),” calls it the “Snackwells Phenomenon.”

Nestle edited the 1988 Surgeon General’s report, which concluded that dietary fat was the most serious problem in the food supply. The assumption behind that recommendation, she explains, was that “If you cut down on meat and dairy, most of your diet would be fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.” She didn’t bargain for Snackwells, a Nabisco line of low- to no-fat cookies introduced in 1992, to help people follow the eat-less-fat advice. “People lined up to buy them,” she says. “I was stunned.” The mistake — and Nestle admits it was a mistake — wasn’t the recommendation to eat less fat. It was a failure to anticipate what people would eat instead, and the lengths the food industry would go to help them follow the guidelines of the day without actually eating more healthfully.

From 1989 to 1995, the percentage of new food products with a low-fat or no-fat claim on the label nearly tripled, from 9.2 to over 25 percent.

Part of the problem, Nestle says, is that the lower-fat versions had about the same number of calories as the full-fat versions, but the “low-fat” label imbued them with an air of healthfulness, and people thought they could eat them with impunity. “Any label like that on a food product makes people think it doesn’t have calories. ‘Organic’ labels make people think it has fewer calories.”

Food manufacturers, she goes on, “are in the business of selling food. They’re not social services agencies. Part of their business is to take advantage of the current dietary advice.”

The low-fat trend wasn’t current for very long. After a couple of years dominating grocery shelves, the number of new products with those claims dropped as fast as they had risen. From 2001 on, they went down to 13 percent or less.

Some of the focus has shifted to sugar. Unilever is reformulating its bottled teas, General Mills its cereals, and Yoplait its yogurts. While some of the reformulated foods are somewhat lower in calories and have been genuinely improved, the silliness of focusing on one particular ingredient is also on display. Sweetgreen, the salad-centric restaurant chain, for example announced in May that it was taking Sriracha, the popular brand of hot sauce, off the menu. Why? “The second ingredient in Sriracha is sugar,” the company said in a statement. With only one gram of sugar per teaspoon, it’s unlikely that Sriracha is doing us harm.

The larger question is whether these changes, some meaningful and some not, will have an impact on obesity and its attendant diseases, or whether American consumers will simply find a way to follow the advice but eat unhealthily anyway. If we opt for vegetables, that’ll be a win for the ages. But if we go with French fries (Hey! No sugar, and didn’t I read that fat wasn’t so bad after all?) and cheeseburgers (ditto), we’re not making much progress.

In the most recent set of dietary guidelines, the U.S. government suggested that previous emphasis on individual dietary components may have been a mistake.

This past January, in its latest five-year updating of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the government floated an explanation for that lack of progress. “Previous editions of the Dietary Guidelines focused primarily on individual dietary components such as food groups and nutrients,” the executive summary reads. “However, people do not eat food groups and nutrients in isolation but rather in combination, and the totality of the diet forms an overall eating pattern.”

Lichtenstein, of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, sees one-thingness as a problem, and emphasizes that we have to look at the patterns and not just the components. Focus on one particular food group or nutrient, and “people figure out how to eat around it,” she says. “You see it in low-carb. You see it in gluten-free. You see it in low-fat. You see it in the singular focus on sugar.”

Unfortunately, diet advice that focuses on patterns doesn’t seem to get traction. Michael Pollan’s “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants” may be the single best example of good advice American eaters just won’t take. Fat intake dipped in the less-fat era. Sugar intake is dipping now. But when it comes to vegetables, our intake remains stubbornly low.

In short, the advice we follow is ineffective and the advice that would be effective isn’t followed. “To a certain extent they’re mutually exclusive,” says Lichtenstein. Where does that leave the legions of doctors, scientists, and health professionals who go to work every day in the hope of helping us conquer obesity?

In a tough spot, say experts like Jacobson, of the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “We’re not going to see declines in adult obesity for decades,” he says. “We have this cohort of people who are 20 and up that has to wash out.”

By “wash out,” he means, of course, “die.” And while he’s clearly not giving up on adults — not after 45 years of doing battle — he’s not the only one who thinks our current food environment makes it prohibitively difficult for grown-ups to change their habits.

“I think education without environmental change is a lost cause,” says Barry Popkin, a professor of nutrition at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “The people who are already educated are the people who follow diet advice. They pay attention, read the paper, and have the money to make changes.” Not so much in low-income and minority communities, where obesity takes its highest toll.

For health to improve among the most vulnerable, Popkin believes that prices have to change. “We need to change the culture of eating,” he says, “but we have very little real food and people can’t afford it. When unhealthy is cheaper than healthy, that’s what happens.” He’s working with countries around the world to promote taxes and market controls that could change the picture.

Nestle and Lichtenstein agree that the food environment stacks the deck against people trying to eat better. “It’s roughly $12 billion a year for ads for food products, restaurants, alcohol,” Nestle says of the food industry, “and for every dollar spent through ad agencies, there’s another two dollars spent on marketing in other ways. People are bombarded.”

Lichtenstein is focused on how easy it is to make unhealthful choices. “When you go to a restaurant, you don’t get whole-grain bread on the table. When you order an entrée, rarely is there a reasonable-sized serving of a vegetable. For the most part, people will eat and drink what’s put in front of them. We have to work to make the default option the healthier option.”

The bickering over who’s right, the anti-fat camp or the anti-sugar camp, seems beside the point when there’s so little confidence that either strategy will have a meaningful effect on public health. The fat and the sugar, they’re the deck chairs. The cheap, irresistible, high-calorie, low-cost food, backed with billions in marketing money — that’s the iceberg.

But there is one potential bright spot.

Marlene Schwartz, director of the Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity at the University of Connecticut, is also skeptical that enough adults can lose weight to produce a shift in population-level data. But she sees hope in the next generation: “My prediction is that in the next five years you’re going to see changes in children.”

Those changes may already be happening. Obesity in children is holding steady, but that’s because it’s increasing among teenagers; among the very young, ages 2 to 5, it’s going down. Kids are also drinking less soda — their consumption is going down faster than those of adults. More importantly, children are being exposed to a variety of programs that address their diet as a whole (as well as their exercise habits), mostly at school. Lunches, snacks, and vending machines are being overhauled. Some schools are planting gardens. And kids are increasingly being taught about cooking and nutrition.

A prime mover in the undertaking is First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move initiative, which Executive Director Deb Eschmeyer describes as a “multidimensional” effort across the entire spectrum of children’s experience — not just more exercise, but “healthier schools, healthier day care, healthier convenience stores.” Let’s Move is the opposite of one-thing; it’s an effort to transform environments. That is hard to do with adults, Schwartz says, but “it’s a lot easier to be paternalistic when we talk about children.”

“Kids who are now in school will have 13 or 14 years of being exposed every day to healthy lunches and snacks,” she says. “This generation will have a better diet than the generation before it.”

Eschmeyer acknowledges that childhood obesity is holding steady for now, but she’s in it for the long haul. “It’s going to take patience and persistence,” she says. “We won’t see the real impact for many years to come.”

In the meantime, if you’re an adult and you don’t want to “wash out,” what should you do? There is good advice out there, says Nestle, and we’ve all heard it. One more time: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

Tamar Haspel is a journalist who has been writing about food and science for nearly two decades. She writes the James Beard Award-winning Washington Post column Unearthed, which covers food supply issues, and contributes to National Geographic, Fortune, and Cooking Light.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

I laugh at all these docs and dietitians full of regurgitating advice from the school books sponsored by big food companies and big phama.

Do you people think they don’t know the crap they are pushing is killing people softly? They know! In fact I would not be surprised if it was on purpose. They seem to come up with drugs constantly in an attempt to keep population alive longer and sicker so they can keep buying the same crap that got them sick in the first place. This is not a joke!

People can fight this by grabbing a hold of themselves and killing the machine by not buying their junk. If a doctors first response is to put you on fist full of pills and ask you to come back later to see if you have side effects, run! They are not doctors! Any monkey can trust big pharma and dish out drugs according to whatever symptom you may exhibit. People need to be proactive and question everything!

And yes.. the crap tastes so good.. how can you not eat it.. right? Get a hold of yourself! It is your freaking responsibility to stay alive and you yourselves are the only ones with control over your quality of life. This whole idea that well it’s not cheap to eat well is such a lie!

I bet you this! Some of you reading this are doinnit or know people who are eating fast food and other crap foods out and about all day long starting with their starbucks mochas and what nots. I have yet to see anyone without a stove top in America. Freaking learn to make your own food! Oh it’s so hard right? A bunch of lazy people who would rather eat some package of crap b cause it says front and center it is good for them. Take charge! Find out why they claim it’s so good. If you aren’t improving, something is wrong! Find out!

Learn what you could change from many sources unrelated to FDA and the big industry! Why? They are all liars and their only objective is to fool the mass for profit! That is capitalism! This is not Utopia where everyone means well and does well. They all hide behind what is accepted to prevent they are trying to do well. Eventually they will come out and say -We’re sorry, we didn’t know sugar in 80 forms in everything was killing you. Just like they did with tobacco.

They know! And they are terrified! People like me have figured it out! They engineer every piece of food out there now. They have virtually managed to control everything you put in uou mouth and they are controlling you with it because it is highly addictive and that is the only reason we are all fat and can’t seem to be able to stop. We are all addicts to the legal cocaine these corporations have been dealing for decades while manipulating guidelines as they pleased with heavy lobbying and with heavy bribes.

Get a hold of yourselves! Stop spending money of fats food thinking it’s convenient. It will rob you eventually of all quality of life and one day you will live to eat like some people I know. They ate themselves so far into disease and immobility that they cannot phantom to anything else but pleasuring themselves with food.

You can’t afford organic? Well don’t buy organic. At least buy greens and learn how to cook them to make them tasty. Eat eggs. Raise your own chicken if you are able. Eat more fish lik sardines, mackerel and salmon even if it is farmed. But most importantly eat greens with every meal. Lean how to quickly wash and sort leafy greens. Stop going to buffets and all you can eat pasta places. You are killing yourselves thinking you ar gettting a deal. They are the ones getting the deal! They are fattening you up into metabolic disease which will destroy your vital organs so they can prepare you for a lifetime of doctor visits, surgeries and pill taking.

It’s not hard even if your poor it’s all about getting off your butt and taking charge! Only YOU the people can force the machine to a halt! Only YOU, the people can make your life better! No new president or any new politician will make your life better. You have the power! Guess what would happen if overnight everyone in America would stop feeding their kids cereal and instead they would have 2 boiled eggs and some broccoli. They would stop producing the junk after a while and would go out of business after attempting some more clever advertising.

And to stop this rant…

Are you tired of feeling dead even though you’re still young? Are you tired of taking pills that are just aggravating your health and wallet?

Stop doing what you’ve been doing! You have the POWER!

Learn to love green stuff!

Eat no more than 9 ounces of meat a day spread over 2 or 3 meals.

Eat dark greens as often as you can!

Count carbs and sugar together and limit them to under 100 per day.

Incorporate farmed eggs of possible, macakarel, sardines and salmon into your diet. Squeeze some lemon on that fishy stuff and eat it! Even if it is farmed.

You may not afford salmon daily or weekly but trust me! you can get it! Just stop eating crap at Mc Donald’s.

Stay away from corn and grains. Grains aren’t that good for us and they are full of carbs and unless you are a runner, grains will just fatten you up!

You don’t need to exercise to start improving your health! One step at a time! First and most important fix your diet! The when you will see result you will want to start moving! I promise you!

Stop eating man man oils. Vegetable oils like corn, canola, soybean and others are just pure poison! Despite what they tell you those oils are horrible. Stick to Avocado oil for cooking at high heat or animal fat, and for salads and such use olive oil.

Don’t be afraid to eat some fat but strive to eat some sources of fat that do have Omega 3 fats not just Omega 6. And on this note, cows that eat grass for a living have far more Omega 3 fat than cows who are fed some formula of corn and grain with added growth factors and steroids. So you may not be able to afford grass fed often but once in a while it is good for you! And yeah you may not be able to buy fresh mackerel and sardines but you can buy them in olive oil or in water and they aren’t that expensive. Cheaper than a lot of burgers from your favorite food porn place.

Start getting involved! Stop listening blindly! Find out what is good fo you on your own! Else you will be taken advantage of by the food industry and pharmaceutical industry.

Tamar, great piece and would love to discuss further with you someday! First, a question: I recently read that there was a change to the BMI chart at some point in the last 10 or 20 years, so does this impact in any way the analysis as the number of people that are deemed obese now as compared to historically has changed? Second, it is troublesome that so many do want to fit this into a binary of carb or fat. I was just listening to the BBC Food podcast on the same issue yesterday. Eat more veg just doesn’t sound fun enough, I guess, though that’s what I spend my time teaching these days.

Such a thoughtful piece, Tamar. It rings true to my handling of my health in the last two years, including losing 70 pounds by doing A LOT OF THINGS including eating all the vegetables I wanted. :) Maybe I’ll tell you more about it sometime. xo

Tamar, great article! I totally agree that demonizing individual nutrients is not sound dietary advice. “Eat a moderate, diverse diet and get some exercise” won’t ever sell books or help food marketers to top into up-sell opportunities, but it is what makes sense.

I lost 70 lbs 344 > 274 simply by cutting out all sugar, except the occasional resistant starch, like a reheated small portion of pasta. No change in activity (except that now I am more active than I have been in 20 years, and am walking, mowing and biking) and all the meat and veggies I wanted, even no-sugar added ice cream. Lost almost two lbs a week and have kept it off.

See an endocrinologist and ask about jardiance, victoza if you are type ii diabetic, and about levothyroxin, and get your vitamin D checked.

BTW, you’ll be surprised at your dislike of sugar and starch after a while.

Great news, but when you say that there has been no change in activity, you then go on to describe A CHANGE IN ACTIVITY!

Cutting out sugar is significant in improving health, (along with cutting out salt, animal fats, and increasing fibre), but increasing activity, as you describe, is another significant way to improve your health.

Good luck!

We have always believed that nutritionists and science will find a way for us to eat all we want of everything we we love, and that all we needed was new fad diet guaranteeing that if we followed it fir a month or two we would lose all that fat we just gained. In my experience, the only thing that works is to eat a little of everything, the emphasis being on LITTLE. When I first came to this country, Americans weren’t fat, and McDonald’s was a fairly new concept in “dining”. I also remember the size of their prtions. A hamburger was about the size if what today is offered in a “happy meal” for a child. Restaurants are constantly offering larger and larger servings. Our insistence on double and triple deckers and super-sizing everything, always topped off with French fries and soft drinks is super-sizing our population, and I see no end to this trend.

Is there any supplement u can use to help in reducing my weight?

No there isn’t

Yes. You can supplement your diet with more vegetables that are low in starches. I recommend the conventionally grown GMO kind:they’re cheaper.

Interesting article. But I don’t think anyone is close to knowing the answer to the problem we have of being fat.

Advice like Michael Pollan’s to “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants” is silly. There’s no meat in that advice, only fluff. It’s like saying the way to promote peace is to “Make love, not war.” It’s a little more complicated than that. People have tried diets like Michael Pollan suggests, and they don’t work any better than any other diets.

Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” initiative suffers from the same problem. She and the people who work for her don’t have any real answers. To give them credit for decreases in childhood fatness strains credibility. That’s all political, not scientific.

Some science suggests that our body’s microbes might have a big effect making us fatter as a nation. Others suggest genetics or epigenetics. But what seems increasingly clear is that this problem is not due to some simple cause — like too much sugar — that can be solved by some simple solution — like a tax on a soda. Clearly, the problem of us getting fat is a complex one that no one has shown a good solution to.

No, it’s not complicated at all… just burn more calories than you take in. If you do that, you won’t be fat. There’s absolutley no disputing that. People are just lazy and stupid, simple as that.

OK, John. Here’s my challenge to you. I am a genetic heritage fat person. But I’ve been thin for five years now. My daily intake is 600-800 calories per day. Why don’t *you* restrict your intake to that amount for, let’s say, a month. Then tell me how you liked that. Contact me through FaceBook.

I have to question some of the statistics used in this report.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans website shows that fat and saturated fat consumption is close to the recommended target.

https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/chapter-2/a-closer-look-at-current-intakes-and-recommended-shifts/

Americans eat a little more fat and a little less oil than recommended, but the overall amount of fat (oil is fat) seems to be as recommended – which is probably not 43%

Between 1970 and 2005 consumption of butter, whole milk, eggs, red meat, and animal fat all declined, as the USDA recommended.

In the same years consumption of vegetable oil, grains, flour, fish, fruit and vegetables all increased.

The major changes are threefold; an increase in carbohydrate from grains and flour (not necessarily sugar), a replacement of saturated fats from dairy and red meat with unsaturated fats from refined vegetable oils.

https://twitter.com/bigfatsurprise/status/754103269853585408

Carbohydrate from refined grains elevates blood sugar and insulin at least as much as sugar, while polyunsaturated fat from vegetable oils, consumed at levels never seen before in evolutionary history, is the precursor for eicosanoid and cannabinoid hormones that promote fat storage in animal models when combined with the amounts of sugar and glucose in the US diet.

The mistake was to eat less animal fat, and Nestle is disingenuous when she says that she didn’t see Snackwell cookies coming. The USDA actually put pressure on food manufacturers to create thousands of such low-fat products, as documented by Dr David Ludwig in the JAMA recently

“The US government advised the public to increase intake of carbohydrates (including 6 to 11 servings of grain products and additional potatoes) and consume all fats (including full-fat dairy, olive oil, nuts, avocado, and fatty fish) sparingly, as exemplified by the Food Guide Pyramid of 1992. To facilitate this change, the Healthy People 2000 goals included a call to the food industry to increase from 2500 items “to at least 5000 brand items the availability of processed food products that are reduced in fat.” The food industry followed suit, systematically replacing fat in food products with starch and sugar.”

http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2564564

The US government cannot pretend that this was not their intention, when the memos ordering these changes are available.

Populations can remain metabolically healthy on diets that are high in carbohydrates, but in all such cases carbohydrate foods are unrefined, all animal foods are eaten with their natural fats intact, and only traditionally available fats and sugars (lard, coconut oil, or olive oil; honey if available) are added.

This is not the pattern which dietary guidelines restricting fat and cholesterol encouraged.

I agree with your analysis, George. In addition, I would point out that primate obesity researchers use an American Heart Association-recommended diet to fatten monkeys for research purposes. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/20/health/20monkey.html