In India, Stakeholders Drive Down Drug Prices for the Benefit of All

Clusters of people stand everywhere — on the lawn, at the main gate, crowding the base of the stairways — at the Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences in Rohtak, a mid-sized city in the northern Indian state of Haryana, about 50 miles northwest of New Delhi. Ailing patients swaddled in wool shawls and patterned blankets linger with their families, some having traveled hundreds of miles from their villages to see a qualified doctor. Many of them are carrying rectangular plastic bags filled with test results and prescriptions in a language they do not speak.

Parveen Malhotra, a doctor and the officer heading one of the main treatment centers located at the facility, known locally as PGI Rohtak, strides through the crowd and makes his way to his office inside the hospital. He knows that many in the crowd are suffering from Hepatitis C.

“My favorite topic is Hep C,” he says with a smile. His office is filled with clippings from local media in Hindi and English about his Hepatitis C work. He goes on local radio and TV shows almost every week to spread the message about the disease and its treatment. He also runs an information hotline from his personal cell phone.

The treatment of choice these days for Hepatitis C involves drugs called “direct-acting antivirals.” Chief among these is a drug called sofosbuvir, which was launched by the American pharmaceutical company Gilead in late 2013. A standard three-month course of treatment can have a sticker price as high as $84,000 in the United States. In Canada, it costs as much as $45,000. And because the drug must be taken in combination with other medications, the price of treatment is often higher.

Here in Haryana state, however, and its neighboring state, Punjab, governments are now purchasing 12-week courses of the drug, plus its companion drugs, for as low as $80 — and they are providing it to their residents for free. This is of no small consequence to Indian activists who have been working for years to drive down the costs of medications available to Indian citizens — many of them outlandishly expensive even for residents of countries of far greater means.

India has long been an important battleground in the ongoing drug-pricing wars. India-based generic drug makers have repeatedly drawn the ire of multinational pharmaceutical companies for copying patented drugs without agreement, but they also proved crucial in driving down prices for HIV drugs used in AIDS relief programs across the world in the early 2000s. Big pharma has fought back, of course, by lobbying foreign governments to enforce intellectual property law to protect their monopolies. But the ability of stakeholders in India — an eclectic mix of activists, government officials, generics manufacturers, and very often, doctors like Malhotra — to force down the costs of Hepatitis C medicine has been heralded as a victory for those who argue that it is a moral outrage to keep drugs out of the hands of sick people simply because they cannot afford it.

In India, the programs in Haryana and Punjab states have been considered so successful that the central government will roll out a Hepatitis C treatment plan for the whole country this year.

“The case of Hepatitis C has opened up a huge precedent across medicine,” said Andrew Hill, a senior visiting research fellow at the University of Liverpool who studies drug pricing. “If we can do it for Hep C, why not for Hep B? For cancer? The potential is enormous.”

While India’s overall prevalence rate of the disease is low, the country’s 1.3 billion residents means that it accounts for a significant share of the world’s Hepatitis C burden. Punjab, in particular, has emerged as a hotspot for the disease. In a 2016 survey, the state was found to have a Hep C prevalence rate of 3.29 percent — three times India’s national rate. Untreated, the virus can lead to life-threatening liver disease and a host of other debilitating health problems.

Punjab’s higher rates of Hep C are due in part to a large population of intravenous drug users, who face a much higher risk for diseases like Hepatitis C and HIV. A study conducted in 2015 estimates that there are some 233,000 users in the state. Many of Haryana’s patients come from districts along the border it shares with Punjab, but data on the number of users in Haryana is less clear. What is clear is that the avenue to the current rock-bottom Hep C treatment prices began here.

“The whole genesis of Hepatitis C response in India is basically based on PGI Rohtak’s [program],” said Leena Menghaney, the head of the legal access program for the group Doctors Without Borders in South Asia.

The Haryana state government has operated a Hepatitis C treatment program for residents for at least five years at the Rohtak hospital, and Malhotra — in addition to serving as the head of gastroenterology — had been appointed as the lead Hep C officer for the facility. In the beginning, only patients who lived below the poverty line could receive free treatment, which was a series of injections with severe side effects given over 24 weeks called pegylated interferon. The drug was expensive, coming in at 400,000 rupees (roughly $6,000) per treatment, and it was rarely used in public health programs in the developing world.

“Most people, including [Doctors Without Borders], had basically said forget it, interferon and ribavirin are too difficult for us to do in the third world and too expensive as well,” Menghaney said.

But Malhotra was determined to treat as many patients as possible. “Everybody should be treated. Everybody’s life should be saved. That is the first motto.” He lobbied his state government to purchase the cheaper interferon supply, which had been clinically proven to be as successful as its more expensive counterpart. The state’s purchasing arm was able to negotiate the injection down to about 100,000 rupees, or $1,500. Even so, because the injections were given weekly, Malhotra said, he sometimes had to give patients train fare so they could get to the hospital. And in any case, he said, the drugs still weren’t cheap enough for the government to treat everyone who was infected.

Not long after Haryana started its pegylated interferon treatment program, Gilead had its first hearing for its patent applications for sofosbuvir in India. Malhotra heard about the drug and was one of the many advocates that asked the Indian government to skip a lengthy registration process because he knew it could have a huge impact.

Low drug prices come about only if certain conditions are cultivated. Creating those conditions means tackling both intellectual property barriers and regulatory barriers, both of which happened in India. While Indian generics makers were trying to develop their own version of the drug, advocacy groups — and even some Indian generics makers — were challenging Gilead’s patent claims in Indian court. At the same time, patient groups approached Indian regulators to fast track approval of the drug for sale in the country. It also helped that there was already a public health program in place which would directly stand to benefit if sofosbuvir was approved.

The conditions needed for generic competition in India were “spurred on by a state government willing to treat, and that is where I think Malhotra and Rohtak played a very crucial role,” Menghaney said. “Because people can say to the government, ‘they’re already treating patients and these drugs could benefit your government program.’”

By late 2014, Gilead had reached an agreement with seven Indian generics companies that would allow them to sell the generic version of the drug on Gilead’s terms. That meant certain quality standards, but it also meant there were certain countries that Indian generics companies couldn’t sell their version of the drugs to. The agreement did not include a fixed price. That was up to the generics companies to decide, said Aaron Brinkworth, senior director for access operations and emerging markets in Asia-Pacific at Gilead.

Sofosbuvir was released in India in late 2015 at around $1,000 for a full regimen, but that was still largely out of the reach of the vast majority of India’s population, where 67 percent of its households earn $160 per month or less. The moment the treatment was available, Malhotra said, he asked the state government to purchase it. While he does not sit directly in the negotiation room, he said, the government listens to its officers in the field for guidance on which drugs to include in their essential medicine list. “It was my suggestion to them that these oral drugs must be purchased on priority,” he said.

A few weeks later, on January 9, 2016, Malhotra was able to offer his patients the treatment.

“Because Rohtak started to negotiate with procurement, the prices came down dramatically,” Menghaney said. “[Malhotra] had the numbers.”

Dr. Parveen Malhotra speaks at the World Congress on Hepatitis in Orlando in 2015.

The real key, those involved say, was patient pooling. State governments pool the number of patients they expect to treat for all sorts of illnesses, and then negotiate with the pharmaceutical companies once a year with this number in mind, explained Menghaney. Generic drug makers then compete to get the best contract from state governments to provide drugs for those patients. Companies were willing to offer lower rates as they would still get a healthy profit from such a large-scale contract. As of December 2017, the Punjab state government has 38,600 people under its Hep C program alone, and it estimates that there are up to 600,000 patients that will need treatment. The Haryana government said it would treat up to 20,000 patients in 2017.

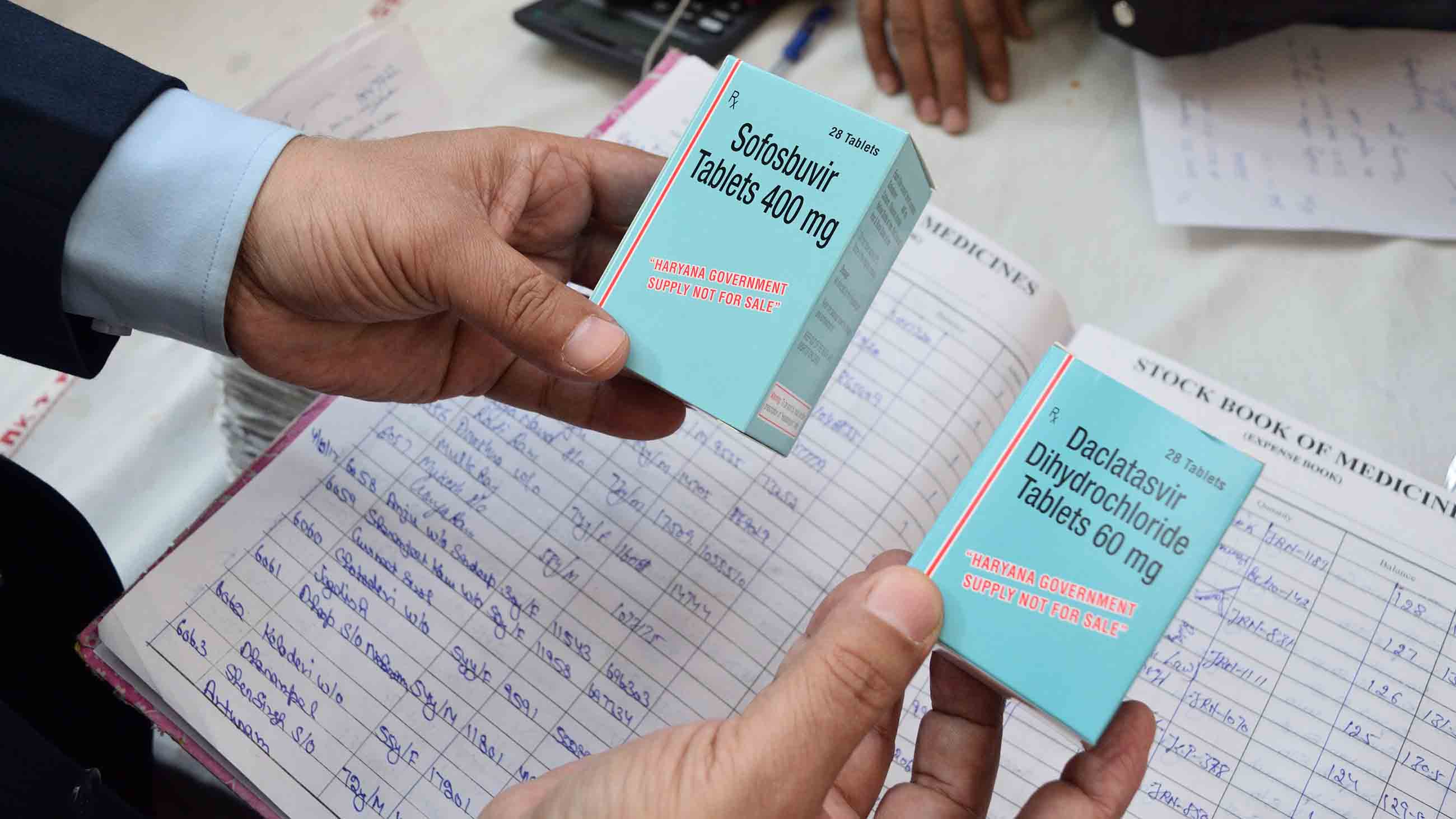

The Haryana government is now paying 5,250 rupees ($80) for a 12-week course of sofosbuvir and another drug, daclatasvir, first developed by the American conglomerate Bristol-Myers Squibb, according to Nishikant Sharma, deputy general manager of tendering at Haryana Medical Services Corporation Limited. The Punjab state government, which launched its own Hepatitis C treatment program in June 2016, pays a price of 7,200 rupees ($110) for a 12-week course of the combined course of sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.

It’s a significant victory for India, but the cheaper prices remain elusive for populations elsewhere. China, for example, has a large number of people living with Hepatitis C, and Gilead has patent applications in process in the country. At present, a sofosbuvir course costs more than $8,900 in China, according to Doctors Without Borders.

Gilead said its licensing agreements in India are not about intellectual property rights, which have been used to protect monopolies. Instead, “we’re really trying to focus on advancing access to the greatest number of patients that we can in the developing world,” Brinkworth said. Under the current terms of agreement, Indian companies can sell their versions of the drug to 105 countries around the world. This list initially left out middle-income countries like Thailand and Malaysia, which had a significant population of people living with Hepatitis C, but that was revised in 2017, Brinkworth said.

Doctors Without Borders is now challenging Gilead’s patents in China. It also shared stories of India’s pricing success with several middle-income countries in Southeast Asia.

Malhotra, meanwhile, spreads his message to other doctors. “Every conference I use to go, every gastroenterology conference, I used to quote the rate there,” he said. That’s because, as Malhotra sees it, millions of people stand to be cured as the price of the drug continues falling.

“My determination is to treat and cure as many patients suffering from Hep C as I can,” he said, “until I die.”

Huizhong Wu is a freelance reporter based in New Delhi, India. Her work has been published by CNN, Wired, Al Jazeera, and The Guardian, among other outlets.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

Hepatitis C is an infection, which is caused by the Hepatitis C virus (HCV). It affects the liver and produces irritation. If this is not treated properly then this virus can be fatal and deadly. According to recent reports, this virus has killed more than 150 million people worldwide. There are also 1.2 crore people in India.

In 1954-55 I planted the seeds for what became the Korean National Health Plan. I had to disobey orders in doing so, and I was punished (by the U.S. Agency for International Development) for the effort. But three years after the seeds were planted, an evaluation committee from the U.S. Public Health Association praised it as one of the Agency’s most successful projects. President Park adopted it for all South Korea two years ahead of completion of the pilot project, overcoming my anxiety by saying, “I don’t care if it isn’t completed – I’ve seen enough to convince me!” So, for over half a century South Korea delivers health care that is better than ours, and much less expensive. (I tried to do replicate it in the U.S., but was thwarted by the physicians’ lobbies.)

Thankfully acknowledge the efficative ,educative, clinically effective,inspiring program being run by Dr.praveen malhotra,n his support team , and genuinely wish to be a part of this team in any manner as I m considered to be deemed fit.I look forward for more informations in this regard from the team .Thanx.